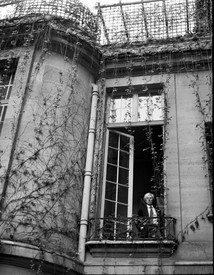

Spencer Sweeney has been a vital presence in the art, nightlife, and music scenes of New York for twenty years. As a musician and performance artist, he was a member of the seminal noise-art group Actress; as a painter and visual artist, he makes collages, paintings, self-portraits, and drawings, as well as environments and immersive experiences, such as the 2010 show in which he moved his living quarters into a gallery space and installed himself alongside the art objects on view. Photo: Rob McKeever

Kembra Pfahler How are you doing, Spencer? Are these all paintings you did in your new studio?

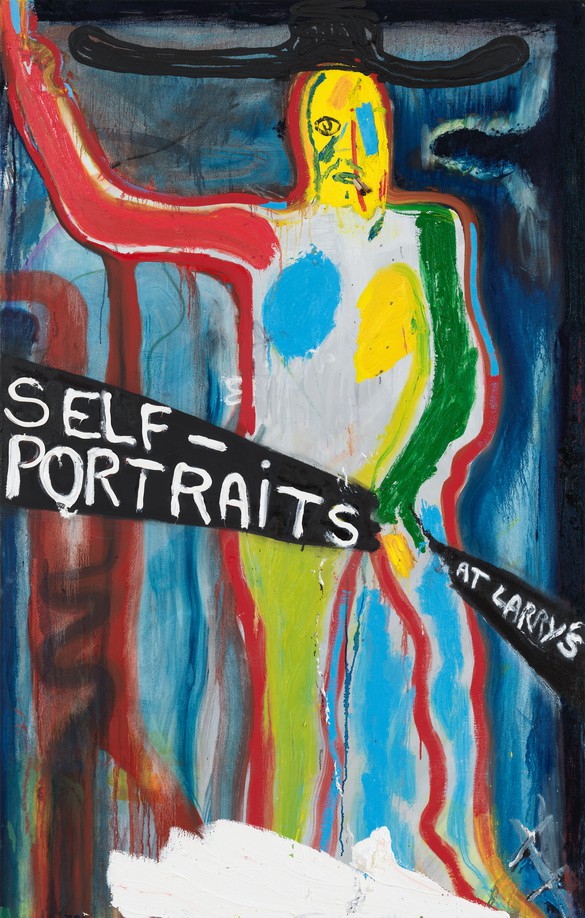

Spencer Sweeney Yes. They’re all self-portraits. That was the idea. I would be in a certain mood and have a certain idea, and I would get started on a self-portrait. So stylistically, I ended up with some pretty divergent works. But then that became something that was important to me, to push that further and create this variety of expressions. I thought that would be a strength.

KP They’re so alive to me. Maybe it’s just that I’m imbuing colors with different meanings, but there’s such lightness in them—like they could take off, in a way. Do you think you can compare painting to playing music or doing your performative types of works? Because you have a performance life too, and a music life, and there’s spontaneity and a lot of experimentation with the music projects you do.

SS Yes, I think there is a significant similarity. There’s a level of sensitivity that you have to have to approach painting, and also playing music, or writing music, or something like cooking. I think it takes a similar head space and sensitivity.

At Headz [a weekly salon cohosted by Sweeney, Urs Fischer, and Brendan Dugan at Sweeney’s studio in 2017–18]—there was a lot going on with music there. You had this synergy, where there were people experimenting with different materials and making visual works, and then at the same time there were musicians who were free to practice pure improvisational music. It was one of those situations where the whole was greater than the parts, because the energy between the people experimenting with visual works and the improvisational music created a new idea or a new experience in a way.

We were talking about similarities between playing music and painting. Some of the paintings in this show have a more minimal approach, and that is because it just seemed at the time to be what would make the most successful works. It reminds me of a quote by Miles Davis: “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play.” And sometimes when you make a mark, the first mark you make is the one you want to keep. But it’s a strange thing, because it can really work either way. Sometimes you want to keep the first mark; at other times you just want to go over it and over it until it piles up.

KP And if you’re listening to your work, it tells you what it wants to be.

SS That’s the thing, if you’re listening, right.

KP You’re such a generous community builder, and you have such an intense private practice too. How is that for you, being solitary and then being with a large group of people? Do you need a lot of isolation to create a show like this one?

SS I need a little bit of both, I think. With Headz, there were so many people and it was every week—I loved it and at the same time it started to really wear on me. And when that ended I holed up in the studio and started cranking through this situation, and then I started to go crazy in there because of the solitude, you know? You go crazy either way, so you have to balance it out.

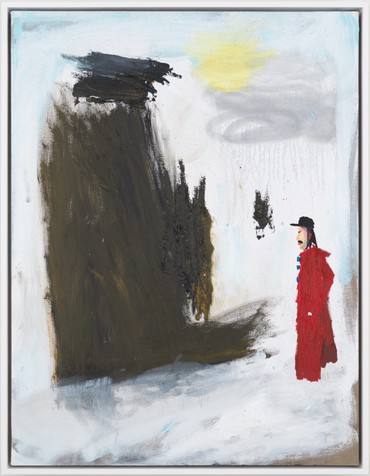

KP These works are incredible, Spencer—they’re giving me the spine-tinglers. This one, especially. It’s like an epic Civil War painting. I’m reminded of Cold Mountain, that film about the Civil War. It was shot in Eastern Europe and has scenes of a soldier wandering around these big mountains—that’s what this makes me think of.

SS People have an interesting read on that one, you know [laughs]. I hadn’t heard Civil War epic yet, but I’m glad to hear that.

KP This one has a lot of emotion in it.

SS Yes, this one I called Suffering Bastard.

KP Suffering Bastard, that’s an intense title. [laughter] I mean, there’s a lot of suffering that has to go into making paintings like this.

SS Yes, it’s kind of insane. I keep trying to figure out how to shake it, and maybe I’ll get there someday.

KP Is drawing a big part of your practice? Is that something you do on a daily basis?

SS Yes, I probably do draw every day.

KP Do you? Or doodle?

SS Yes. I’m a doodler. I’m always drawing. I used to get into trouble for drawing because I couldn’t stop. That was in high school, I guess.

KP Can I ask you about your performance practice? There are a couple of inspirations that you’ve spoken about before that are really interesting to me—the Eastern European folks. There was the one person that you studied—

SS Oh, Jerzy Grotowski, yes. He wrote a magnificent book called Towards a Poor Theater, and it’s loaded with some very valuable philosophical gems. Especially if you’re working on performance—he really gets down to the mechanics of the whole thing and has a wonderful, astute, visionary take on it all. He’s a genius.

KP Did you have a good experience in school? I’ve found it incredible to work with students at Columbia [University’s School of the Arts]. It’s a really intense time, I think, to be a young person in school. Did you have a school experience that you enjoyed?

SS Yes, I did. Now, with tuitions being what they are, there is so much pressure. It’s kind of like: Figure out what the hell you’re going to do and pour $200,000 into it, and whoosh, that’s it, that’s your life; it better be it! That’s a pretty tough situation, really.

KP Yes, that’s true. It’s almost surreal to see students going through the machinations of being in university in 2018. “Is there a future for us, and what’s up with life,” you know? I don’t think anyone has an answer to what the future will be, because it’s changing so rapidly.

SS Nobody ever really does, is the thing; there’s always that uncertainty. Although I was reading a book called The Order of Time, by Carlo Rovelli. He’s a great writer. He breaks down theories of quantum physics in a way that makes it possible to process them. And he writes that the whole notion of past, present, and future, the whole notion of time, is a distortion, and it’s there because we can’t see the workings of the universe down to the smallest parts that exist. If we were able to see everything that was going on around us, then time would cease to exist for us; we would no longer need this whole concept of past, present, and future if we were able to see things in their true state.

KP Thich Nhat Hanh talks about that as well.

SS Yes.

KP And mostly about remaining in the present.

That whole mindset that you can’t do something is completely against what creativity is all about.

Spencer Sweeney

SS That reminds me of a quote by Hilma af Klimt that I heard the other day: “Stay inspired and forget what you’re doing.” That has a certain disregard for time—for the past, for the present, or the future. All you need to do is stay inspired and forget about the rest.

I had a great amount of anxiety when it came time to finish the works for this show, and I was driving myself crazy. And then I just had to forget it. I had to get myself into a head space where I was like, there actually is no time, I just have to do what I do and not think about the rest.

KP The reason I spoke about the paintings seeming so airy and ethereal is because I’ve seen you do a lot with thicker paint in your other exhibitions.

SS Yes, sometimes the application gets really thick and aggressive, and sometimes it stays lighter. These are more gestural.

KP It’s really a vulnerable thing to do a self-portrait, also. To do a self-portrait is like doing a solo performative gesture, in a way.

SS At times it’s kind of a painful thing to do. But it helped me out too, because there were things to think about, and it appealed to my sense of humor on a lot of levels as well—you know, playing with this idea of narcissism and things like that [laughs].

KP Studying ourselves and our own reservoir, our own history, our own experiences, will forever be an abundant source of content and information. You’ll never run out of ideas.

Spence, you were saying earlier that you had to edit your paintings when it came time to install them; you had to select which ones to show. Was that a film-like process at all? Because your background is in film—I mean, you have a pretty diverse background; it’s very interdisciplinary.

SS Well, I think the most important part of my education, aside from art school and drawing and painting classes, was that I grew up on the revival movie house scene. I would hang out at the different cinemas, and that was a great education. I was turned on to so many wild films and ideas. But as far as editing goes, I don’t know, I really don’t picture it as being a filmic process for myself.

KP There is a lot of diversity in this room too.

SS A lot of different things have happened that lead me to different styles of art making and making pictures. That whole mindset that you can’t do something is completely against what creativity is all about. When I was in art school, it was popular to say that painting was dead. This was in the mid-1990s or so, and it was all about new media. If it wasn’t new media, then it was considered a dead art. I just thought, this is so counterproductive; you’re naming a mode of work to be no longer legitimate because you’ve found a new legitimacy. What? [laughs]

Spencer Sweeney: Self-Portraits, Gagosian, Park & 75, New York, November 9–December 22, 2018

Artwork © Spencer Sweeney; photos: Rob McKeever unless otherwise noted