Edek Bartz is an Austrian musician, DJ, concert promoter, curator, author, and lecturer at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. He is coeditor of the book Secret Passion: Artists and Their Musical Desires (2010), based on a series of public conversations with renowned artists and architects on their emotional relationship to music.

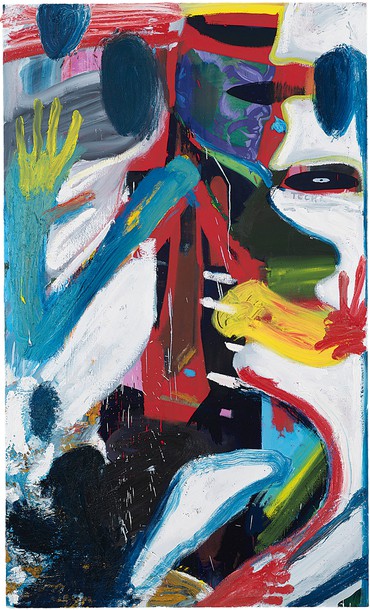

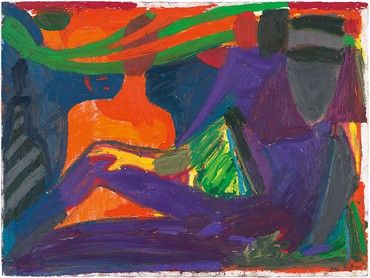

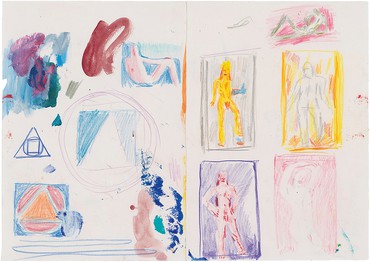

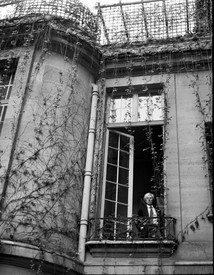

Spencer Sweeney has been a vital presence in the art, nightlife, and music scenes of New York for twenty years. As a musician and performance artist, he was a member of the seminal noise-art group Actress; as a painter and visual artist, he makes collages, paintings, self-portraits, and drawings, as well as environments and immersive experiences, such as the 2010 show in which he moved his living quarters into a gallery space and installed himself alongside the art objects on view. Photo: Rob McKeever

Edek BartzSpencer, so how is life?

Spencer SweeneyLife is pretty good, Edek.

EBI was looking through your exhibitions from [2014] and it was quite interesting to see how different they were. In Brussels [She, at c l e a r i n g gallery], you made a really elegant exhibition of small paintings and drawings, with one painting hanging over the fireplace. A friend of mine who also saw that show told me he expected from you this kind of exhibition, these kinds of paintings, nice little drawings, and then empty walls. In Glasgow [Monads and Party Paintings, at the Modern Institute], the exhibition was full of big works and it really filled up the whole space. How do you think about doing an exhibition? Do you think about the space first, or do you have an idea of what you’d like to show?

SSThose two situations happened quite naturally. I also have several different modes of working that come forth. Sometimes the expression can end up being quite simple and maybe have a simple elegance to it. That’s just something that I like to explore when the mood hits me. At other times the work can be much more aggressive and busy. There are just different moods that come over me that I explore while I’m working. As far as how those shows wound up, I took a look at the space in Brussels and it was this very beautiful townhouse. As soon as I saw that, the first thing that popped into my mind was smaller, more subdued works. That’s something I’m interested in and something I do from time to time. That kind of mode of work seemed to fit within that space, so I thought I would try it out. Then it was also interesting to play with the sparseness of the works, working with fewer paintings and drawings and playing with the spatial relations and the negative spaces between them.

For the Modern Institute show, that’s a much bigger space with lots of very high ceilings and lots of wall space and it just seemed like the right thing to do at that time. We sent over a bunch of work and started playing around with different installation ideas. One wall called to be filled from floor to ceiling all the way up the wall. On another wall, we decided to hang the work very low, close to the ground. We left another wall completely blank.

For me those two shows were both about experimenting with installation. I learned a lot from being put into that situation of dealing with those two very different types of gallery spaces. I hung the Brussels show together with my friend Harold Ancart. We had a long night and a day of discussion where we explored different configurations and possibilities. It’s nice to work with another artist you’re friends with and whom you respect. That seems like an important part of the creative experience, or the artistic experience—being able to chat and go through ideas with another person who is alive and doing the same thing.

EBThe show you did with VeneKlasen/Werner, Berlin, in 2013 [Berlin Paintings] was again a totally different kind of show. Every show that I know now is really completely different. There’s always your work, but the setup is totally different. In Berlin, you lived in that space, right?

SSThe show in Berlin was a continuation of a kind of experiment that I started at Gavin Brown’s the fall before that. Rather than set up an exhibition of art objects and then leave, the idea was to transform the gallery into a studio and a performance and theater space wherein I would ask some people to collaborate. We would work on a piece of theater together and all the time be working on paintings and sculptures, and then we presented the theatrical piece at the finissage, when the show ended.

EBDo you like working with other artists? Not only visual artists but musicians and people from the theater and from other art styles?

SSI do, I do. I think that kind of communication is very important; well, it’s very important to me. But I don’t always choose to work that way. I do like to work alone as well. I find that I need to do both to be satisfied. I need collaboration and I need that type of interaction and communication and the synergy that comes about through it. At the same time, I need to work in solitude quite often as well.

EBIs it the same when you play guitar in bands with your friends? Is it about playing music, about being a rock musician, or about a kind of communication?

SSIt’s definitely about communication and the experimentation and the creative process and just the love of music. There’s the love of music. There’s the love of art and that’s what drives us to spend our time doing this.

I’ve been playing guitar with my friends Sadie Laska and Lizzi Bougatsos. They’re both musicians and visual artists as well. It’s just something we’ve always done, actually—I’ve been playing with them for as long as I’ve been in New York. Soon after I moved here, I met Lizzi and Sadie and we started playing together in a band called Actress. Musically it was complete improvisation. Now we’ve been improvising together for quite a long time, so it’s interesting to continue with that and see how these skills and this unspoken language develop. It’s like cooking, playing music, painting, or working on performances, it all somehow seems to boil down to utilizing the same kind of sensitivity. That’s something that’s important to us, and that seems to be what we strive to spend our lives doing.

EBIs there a difference if you’re playing with professional musicians or with artist friends?

SSI think it’s very similar. Maybe you could define the professional attitude as taking what you’re doing seriously and challenging yourself. That’s kind of how we play together, even when we’re improvising. Even if some of us aren’t professional musicians, we still take it quite seriously and still push ourselves very hard to create something that we find musically interesting. The difference is, I’ve gone on tour with professional musicians and then you have the framework of their material to present. But at the same time, within that framework, there’s a great amount of opportunity for improvisation. I’d say it’s very similar. It just depends on your approach to it and how seriously you take it.

EBIs music an important part of your life?

SSYes. It’s always been. Sometimes I think I can only blame my mother for that, because I was born a couple of months premature and had to spend a long time in an incubator. My mother requested that they pipe the classical-music radio station into my incubator. I can’t get the music out of me now. Music is very much a part of my physical makeup.

EBWas it rock music that really got you in the beginning? What was the first music that made you think you wanted to make music too?

SSIt’s funny, because this is kind of a model for what I continue to do. The first musical experience I can remember is sitting down with my mother’s copy of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, listening to that, and at the same time drawing on the album cover with crayons. I still have that album. I opened it up to the centerfold, where you have all four Beatles sitting there in their psychedelic bandleader outfits with a bright yellow background. I immediately reacted to the rich, saturated colors in that print, and I started drawing all over the Beatles with crayons while listening to the music. I was reacting to the music and I was reacting to the color of the photographic print and partaking in that by drawing on it myself. I think that’s what I still do—I’m always listening to music as I’m painting.

EBDo you listen to everything at the same time? Or do you have times where you only listen to one style of music?

SSI think there’s a pretty healthy mix going on, because I do love to listen to classical music and I do of course love to listen to rock and funk and different types of dance music and African music. I’d say it’s a mix of exactly those types: classical, rock ’n’ roll, things that would have to be considered more experimental, funk, dance music, reggae, African music. That’s pretty much it.

EBThat’s your song mix—it seems great. You sent me some YouTube videos of classic Egyptian Arab singers like [Mohammed] Abdel Wahab. Are you interested in this?

SSVery much so—especially Abdel Halim Hafez, whose video I sent you. There’s a very poignant beauty there, because at the time those films were made he was dying of cancer and doing pain management with different medications. There is a real beauty in that tragic kind of situation, and there’s this great amount of drama that comes forth when people express themselves at a time when they’re facing mortality so closely. The guy’s such an incredible talent and I just thought that film was really remarkably special. That’s why I think it’s such amazing music—it’s such an amazing outpouring of emotion.

EBDo you know Abdel Wahab, Umm Kulthum, all that classic stuff?

SSI know what I know and I’m learning—I’m definitely no expert on the genre.

EBHow did you find out about Omar Souleyman?

SSI met Omar when he played at our club. I did a painting to advertise the show and his manager called me and said Omar really loves the painting. I said I’d like to give it to him. She arranged for us to meet the night after the show and I was able to give him that painting and meet him, which was really great. His manager translated for us so we got to hang out and talk for a while. Then they asked me to do an album cover for his next LP, so I did that, too. That’s how I got to know Omar.

EBIt’s a great cover. I bought the record just to have the cover.

SSIt’s a funny story—I don’t think Omar likes the cover. I was talking to Joe Bradley at an art opening and he was like, “I was reading how you did the painting for the Omar Souleyman cover.” I said, “Yeah. What an honor it was to do the artwork for such a great performer.” Then he was like, “Yeah, he was talking about how he didn’t really like it. He felt it didn’t really capture him in a way he was happy with.” I was crushed. I just went home and got very depressed. But I’m over it now.

EBI think it looks great. I’ve had this experience a few times—when artists work with musicians, they’re never satisfied with the cover.

SSI think that’s really part of the creative vision within an artist’s head, and how it exists as it travels from the headspace into the physical world. An artistic vision is something that is perhaps never achieved. What you get is the artist’s attempt and the limitations of the physical world. It’s always a different thing, and it’s very difficult. I wasn’t happy with the album cover either, because the designer muted all the colors. I was going for a major impact with this red, and when I got it, I was like, “What the fuck happened?” The designer said he was trying to make it look like an old classic album cover. I was like, “You didn’t!” I was really upset and then Omar was upset. But at the end of the day, it is what it is, and it’s a great album. I’m glad I was able to be a part of it.

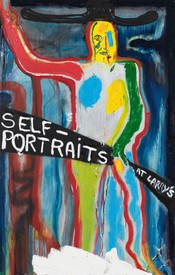

EBThis brings me back again to the Glasgow show, because you had this wall with your posters. It was funny because when you came [to the SoART artist-in-residence program on Millstätter See, Austria, in 2014], you sent me the list of things you needed and it read something like “canvas for party paintings.” I remembered that the email announcements for events at your club always come with a drawing or something. So I want to ask you, why are you doing these “party paintings” on canvas?

SSI’m doing them on linen. It’s really just what I had lying around at the time. I felt like if I wanted to use a good amount of paint, or work wet on wet, then it couldn’t be a work on paper—I needed something that was really durable, and I thought that linen would be more versatile than anything else.

EBIt was a practical decision, because this was the easiest way for you?

SSYeah, well, I had a bunch of linen around. I knew the linen would be more versatile than paper, but also I started to enjoy the idea of it being a poster, which has a pragmatic functionality to it, and then using this kind of fine-art material with a history to it. I was enjoying that relationship as well.

EBWhat is it like to do a poster for you?

SSI have a serious connection to poster art, actually. It’s very much within my history and my background in growing to understand the visual arts. As a young child, I would collect fliers for punk-rock shows—mimeographed letter-sized fliers. It introduced me to the work of people like Raymond Pettibon and Pushead, who’s a great album-cover and poster artist. I used to go around and take them down from the streetlights where they were taped. I still have a big stack of them. I remember looking at the Raymond Pettibon fliers for Black Flag and thinking, I’ve really got to try this because I think I can do this.

So there’s that, and also a strange experience I had in grade school when I copied a Toulouse-Lautrec print. We were presented with a large cardboard box filled with images and the assignment was to copy something. My choice was a Toulouse-Lautrec print of a woman in a hat with opera gloves on. Later in my life, much later, I realized it was actually a drawing of a man in drag. As a child, I didn’t know that—I was seeing her as a woman. I’ve always enjoyed that connection as I do these paintings to advertise parties and shows at the club. I’ve enjoyed thinking about Toulouse-Lautrec and how he did the same thing for the Moulin Rouge.

EBNext time you come to Vienna, I’ll introduce you to my friend Bruce Meek. He’s an English guy. In the ’70s he did a lot of psychedelic posters for the Fillmore East and West and all the psychedelic album covers.

SSOh wow—I’d love to meet him.

EBHe’s a very nice guy. He’s a friend of Procol Harum and all these bands, because they all grew up together. He couldn’t be a musician so he decided to make posters. He lives next to my house, on the corner. I’ve had these records for twenty-five years and now I meet him. That’s quite interesting.

SSI’ve always been lost in certain album covers. I have very early memories of spending a lot of time looking at album covers, so that’s there, too. And actually I’ve done a few album covers. I did the Omar one and then I did one for Will Oldham. I did one for TV Baby. At a certain time it seemed as if the vinyl LP was going to be completely obsolete and would just stop being manufactured, but it hasn’t. In fact it’s experiencing a revival, which is great. People really held on to it and it has a lot to do with the sound quality—it’s a really great-sounding format if played through a good system. All the artwork I’ve done has experienced releases on vinyl and has been printed on album jackets. That’s pretty great. It’s a healthy industry. Surprisingly enough, it persevered.

EBI’m buying all the Sun Ra record reissues—they have these great sleeves, which are made by Sun Ra himself.

SSThose drawings are amazing. So good. There’s a very healthy reissue market taking place. There are all these record-printing plants organized to get the licensing and agreements to reissue all kinds of rare records that for a long time were very hard to find. They’re doing a good job, too—they’re putting out quality pressings.

EBYeah, the 180 grams. That’s really very good quality.

SS It’s really nice when you can get it on a nice, thick piece of vinyl like that.

EBMany years ago, I was with Urs Fischer in Vienna giving a lecture about music. I always ask artists to bring the ten or fifteen most important records in their life. I just want to sit down with them and put on the records and listen to them. You know Urs, yes? What do you think would be his taste?

SSLet’s see. I was hanging out with him and Tony Shafrazi a couple of nights ago and we got into a big argument over music. It was over what they like and what I don’t like, I guess. Urs and I enjoy a lot of the same music, our tastes can be quite similar, but Tony started talking about that band Gorillaz, which is the guy from Blur or something? They made this cartoon video and I think that’s a real low point. I can’t stand that kind of stuff. I just find it fucking horrible. We got into this thing and Tony’s like, “What do you mean you don’t like the Gorillaz? You don’t like these cartoons?” I’m like, “No, I hate that stuff.” I just completely went off. I was in that kind of a mood.

EBAt the time when I did the lecture with Urs he was a young guy, really covered in tattoos, as you know. I think it was 2000. The lecture was at the university of applied arts in Vienna. First of all, the students thought he was another student, because he looked like a student. And also when they saw him, they assumed he was kind of a hard guy who would listen to semihardcore music. And what he played was really incredible because it was only soft, romantic stuff like Willie Nelson, country music, Diana Ross. The kids couldn’t believe it. By the way, I made a book out of this [Secret Passion: Artists and Their Musical Desires]—it’s really funny to read about different artists’ musical tastes and also the explanation of why they like this track, this band, and so on.

My mother requested that they pipe the classical-music radio station into my incubator. I can’t get the music out of me now. Music is very much a part of my physical makeup.

Spencer Sweeney

SSI want to see this book. I think there was a point up until the early 2000s where it did seem like people who appreciated a certain kind of music had a certain look that was in unison with the music. People expected that, in a way. Thankfully, I don’t think that happens quite the way it used to. I don’t like for things like music to be so uniform oriented. Unless you’re Devo.

I remember moving to New York and some of the first work I was able to get was as a DJ. It used to be that when you’d go into record stores, people would ask you what kind of music you played. It was all very specialized at that moment and you were expected to say that you played progressive house music, or trance, or whatever. People felt like they had to stick to a genre. That was a big question at the time musically, it was just kind of the way people felt it had to be, I suppose—it’s not so much that way anymore. I could put a mark on when it started to happen, it was right around the end of the ’90s—the 2000s was the point where everyone just loosened up with identifying and sticking with genres. Things became much less specific and genre-oriented as far as DJ culture goes. Especially since the Internet has opened up this instant transfer of information, that kind of idea has really loosened up. You find people being exposed to all types of things without having to walk a certain path in their lives that might have led to an attachment to a certain lifestyle or look. It’s interesting to see things change like that. Urs was part of that change in the story that you told because people were expecting him to be into a certain thing, but he is into many different things for many different reasons.

EBThat’s why I told you this story, because I thought it was really interesting. It’s not to fulfill the expectation. Just do what you do. Do you think it’s the same in art, that the artist is getting more specialized? Is it similar to music, or is it totally different?

SSWow, I have to wonder. I had only really thought of it in musical terms so far, but I can theorize about the effect this might have on the artistic community and visual arts. Basically, I think you have to look at the transfer of information over the Internet as an opportunity for a heightened state of awareness. That’s the good side of it. What we’ve seen happen is, there seems to be a proliferation of people living as artists, working as artists. I’ve seen that happen within the past ten or fifteen years. There definitely has been a huge growth in that profession—people working as professional artists. That also might have to do with there being more information available. People know more about artists. It’s all there, and people are learning so much. I also think it might be a generational thing, where people who were able to participate in the countercultural activism of the ’60s may be more open to the idea of sending their children to art school. That could have something to do with it. I don’t know, but I can see it’s having a huge effect on the world culturally as far as what you might call pop culture. It’s made a very significant mark on the geography of pop culture. People are very aware now. A larger group of people is more aware of the creative community than I think they ever have been.

EBBut it also happened because you always read in newspapers and magazines about this incredible wealth of artists. You don’t read about art; you only read about what they have, they have these incredible castles and they have this and they have that. You only read about money and figures. You think this would be a good career because it looks quite easy. It’s not. But it looks like it is.

SSYeah, and we’ve been identified as if we’re out to accumulate huge wealth.

EBTwo days ago I was in a little rock place in Vienna. There was a band from America called Slim Cessna’s Auto Club, one of these independent little bands that are playing in small clubs. They put on an incredibly good concert. The band is getting maybe $2,000 for the concert, but they’re five people and they have to pay for their own travel—so the real money they’re getting after the gig is maybe $200. But they love to play and you really can see and feel and hear it. There’s no money in this normal music business.

SSYeah. It’s troubling if you consider the state of the art market and how it’s an overblown bubble in things like auction activity and other matters. You see the focus shift from the quality of the personal expression of an artist to things like the power and the commerce of the whole thing. As an artist I find that sickening, but at the same time there’s a positive—I feel very fortunate that I can live off of my artwork. But it’s troubling to think of a young artist entering this market and trying to focus beyond how many pieces you can sell, or what you can do to make it sell, or how you can make as many works as possible. That’s not what artistic drive should be. It’s a strange thing . . .

Edek, you’re such a good storyteller—I was just thinking of that story you once told me about when you brought Jimi Hendrix to play at the concert hall in Vienna.

EBIn the Konzerthaus? I think it was 1969. At the time, there weren’t any rock venues in Vienna. The only venue we could book was the Wiener Konzerthaus, which is a classical venue where classical concerts are normally held. We booked this venue for him and the equipment arrived—these twenty-five huge Marshall amplifiers and all these instruments. It was clear it was going to be really fucking loud. This was absolutely clear. What didn’t arrive was the light system, the spots. We very quickly rented two small lights where you can push them up and have ten bulbs on the left and right.

Before the concert, the police came and checked the stage to see if everything was secured and in order. They looked at the Marshall amps and said, “What’s this?” I said, “These are the lights.” Then we pointed up at the lights and said, “This is the sound.” This was the end of the ’60s—we could do this because nobody knew better at the time. When Jimi Hendrix started to play, it was so loud that people were sitting on the floor, not on the chairs, because they thought it would be less when you sat on the floor, which is of course stupid. They had the impression that they could hide or something. I was backstage and Jimi Hendrix came back during the set and said, “What happened? Why are the people sitting on the floor?” But the funny thing about the concert was that it was so loud that in the next room, which was quite far away from this one, the glasses and the bottles fell down. It was so loud that the whole building was shaking. Everything was vibrating. It was a great experience.

SSOh my God, yeah. Cool.

EBIn 1971 I worked on a Pink Floyd concert at a music festival in Carinthia. One of the biggest Austrian classical piano players, Friedrich Gulda, set up this festival with world music and rock music and jazz and everything, and he had the idea to invite Pink Floyd. Today you can’t even imagine how this could happen—that we could get Pink Floyd to come play in a little village in Carinthia. I don’t know how we managed to convince them, but they were coming, and we set up the show in the backyard of a very beautiful baroque church. It was, of course, sold out, and we’d been really relaxed about the show.

The first part of the program was the orchestra playing a Mozart piano concerto with Friedrich Gulda, and the second part was Pink Floyd. You could see Pink Floyd’s equipment on the stage and, in the front, the music stands and chairs of the classical orchestra who were the supporting act. The village police officer came and said we had to immediately cancel the show. He had heard from the traffic police that thousands of cars were coming. We said that was good for us but they said the village was too small and we had to cancel. I told him that it didn’t matter if we canceled because they were coming anyhow, and if they got there and the show wasn’t happening we would really get in trouble. I pretended that I was so professional, and that I had a lot of experience working on many big open-air shows and therefore knew how to handle this, which was of course a lie. After he left I realized that we were really in trouble if thousands of people were coming, because in that venue you only could sell seven hundred tickets, which is nothing.

So we decided to turn it into a free concert. We opened the doors, and in came three or four thousand people. And of course the village was out of control. All the kids were lying in the grass, on the lake, and fucking around everywhere. It was like Woodstock in the Carinthia. It was a great evening but the next day, the village looked like a huge trashcan and the mayor came and immediately told us this was the end of the festival.

SSThat’s a great story. What a great experience. And you went back last year?

EBI wanted to see it again, because I never had the feeling that it was so small. But I was standing in this church, and it’s incredible that anyone could have had the idea of doing a Pink Floyd concert there. We thought the church would be a nice backdrop for the band, but they’d already done the double album, Ummagumma (1969), and were already a very famous band.

Spencer, I want to ask one question: When I look through your work I see a lot of portraits, but they don’t seem to be of real people. What is it about with the portraits?

SSIt’s a combination of things. When I’m painting, I often become very involved with these different personalities that come about. If I’m to sit down and start to draw a figure, I become engaged with these different personalities, these different spirits. It’s something that I keep going to almost automatically. It has to do with this certain idea of souls, just different, unique human characteristics. This is what a soul is. Sometimes I sit down to draw and a face comes about. I’ll find that it bears a striking resemblance to someone I know and it has come about without me looking for it. At other times I will sit down with somebody and do their portrait. I enjoy that experience very much. It’s an automatic process of a personality that comes about from the motion of my hand and from my imagination. I like the format of the portrait. There’s this kind of singular expression, maybe, say, a facial expression, that becomes the focus of the work. I also like how on the side there are little hints that tell a story in terms of the dress or the location, the environment in which the character sits. I enjoy that format very much. I find myself making a lot of portrait-sized canvases. That’s something I really enjoy. I enjoy playing with the historical aspect of that.

I also just enjoy having this character come forth in a very automatic way, almost straight from the subconscious. To me that’s a pleasing kind of process to embark upon and see through. It just really appeals to me. There are levels to it. It becomes a psychological study, which you can turn on to yourself, and it also becomes an expression of the different characteristics of human psychology and emotion. To me, there’s a lot to focus on.

EBI think it’s a really interesting aspect in your work over the last years. Spencer, this evening I’m going to see a movie about chaabi music [North African festival music]—there’s a huge movement in Egypt now, these new rap guys. It’s really, really interesting. I’ll send you a link. You have to check it out.

SSOh, yeah. I want to check out the Egyptian rap scene, for sure.

This is an edited version of an interview originally published in Spencer Sweeney (Brooklyn: Kiito-San, 2016).

Artwork © Spencer Sweeney; unless otherwise noted, photos: Rob McKeever