About

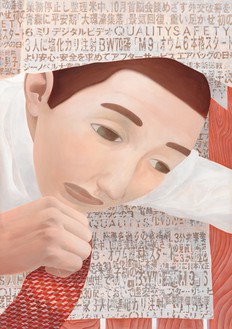

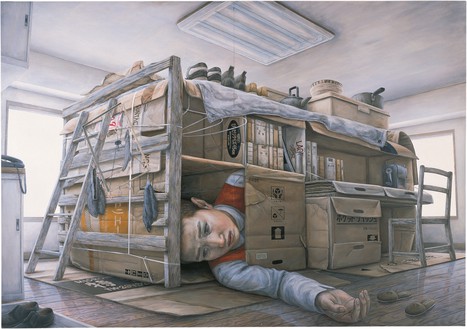

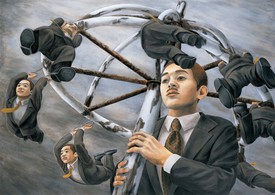

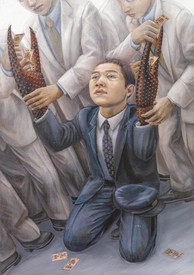

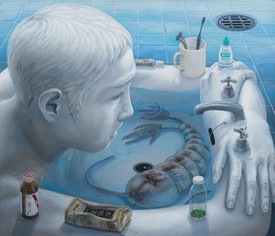

At first, it was a self-portrait. I tried to make myself—my weak self, my pitiful self, my anxious self—into a joke or something funny that could be laughed at. It was sometimes seen as a parody or satire referring to contemporary people. As I continued to think about this, I expanded it to include consumers, city-dwellers, workers, and the Japanese people.

—Tetsuya Ishida

Gagosian is pleased to announce My Anxious Self, an extensive exhibition of paintings by the late Tetsuya Ishida (1973–2005) at Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York, opening on September 12. Curated by Cecilia Alemani, the survey follows the announcement of Gagosian’s global representation of the Tetsuya Ishida Estate, which, along with notable private collections and the Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, Japan, lent more than eighty works to the exhibition. My Anxious Self is the most comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s work to have been staged outside of Japan, and his first ever in New York.

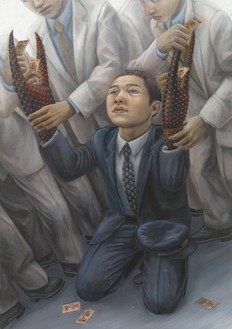

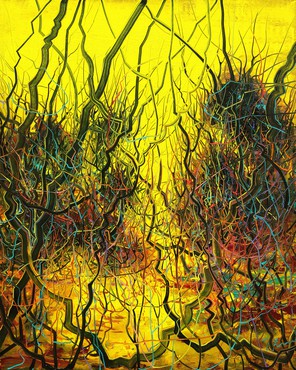

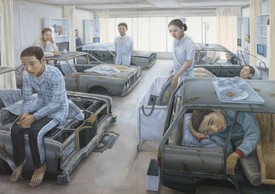

Over the course of just ten years, Ishida produced a striking body of work centered on the theme of human alienation. He emerged as an artist during Japan’s “Lost Decade,” a recession that lasted through the 1990s, and his paintings capture the feelings of hopelessness, claustrophobia, and disconnection that characterized Japanese society during this time—even in the wake of its rapid technological advancement. Before his untimely death in 2005, Ishida conjured allegories of the challenges of contemporary life in paintings and works on paper charged with Kafkaesque absurdity.

In his introduction to the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, Michiaki Ishida, the artist’s brother, confides, “Tetsuya’s wallet, which he kept until the end of his life, contained several American one-dollar bills. Perhaps it was his wish to go to New York, the center of contemporary art, one day. We are grateful that he finally has a chance to spend them.” Larry Gagosian, in his foreword to the publication, observes that Ishida’s oeuvre constitutes “a grand inquiry into the human condition in a way that feels urgent, timeless, and unusual for an artist so young.”

#TetsuyaIshida

Artist

Download

Press

Gagosian

press@gagosian.com

Hallie Freer

hfreer@gagosian.com

+1 212 744 2313

Polskin Arts

Meagan Jones

meagan.jones@finnpartners.com

+1 212 593 6485

Nostalgia and Apocalypse

In conjunction with My Anxious Self, the most comprehensive survey of paintings by the late Tetsuya Ishida (1973–2005) to have been staged outside of Japan and the first-ever exhibition of his work in New York, Gagosian hosted a panel discussion. Here, Alexandra Munroe, senior curator at large, Global Arts, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation, and Tomiko Yoda, Takashima Professor of Japanese Humanities at Harvard University, delve into the societal context in which Ishida developed his work, in a conversation moderated by exhibition curator Cecilia Alemani.

Tetsuya Ishida: My Weak Self, My Pitiful Self, My Anxious Self

The largest exhibition of the Japanese artist Tetsuya Ishida’s work ever mounted in the United States will open at Gagosian, New York, in September 2023. Curated by Cecilia Alemani, the show tracks the full scope of Ishida’s career. In this excerpt from Alemani’s essay in the exhibition catalogue, she contextualizes Ishida’s paintings against the background of a fraught era in Japan’s history and investigates the work’s enduring relevance in our own time.

Tetsuya Ishida’s Nihilist Realism

Mika Yoshitake details the economic, psychological, and cultural conditions that gave rise to Tetsuya Ishida’s unique strain of Japanese postwar realism.

Tetsuya Ishida: Painter of Modern Life

Yūko Hasegawa explores the fantastical convergences and amalgamations in Tetsuya Ishida’s paintings, their connections to manga and advertising imagery, and the shift that occurred in the artist’s work as he moved from acrylic to oil paint in 2000.

Tetsuya Ishida’s Testimony

Edward M. Gómez writes on the Japanese artist’s singular aesthetic, describing him as an astute observer of the culture of his time.

News

Tour

Tetsuya Ishida: My Anxious Self

With Cecilia Alemani

Thursday, October 12, 2023, 5pm

Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York

Join Gagosian for a tour of Tetsuya Ishida: My Anxious Self at Gagosian, New York, led by exhibition curator Cecilia Alemani. This comprehensive survey of paintings by the artist, divided into five thematic parts, is the first-ever exhibition of his work in New York. Ishida emerged as an artist during Japan’s “Lost Decade,” a recession that lasted through the 1990s, and his paintings capture the feelings of hopelessness, claustrophobia, and disconnection that characterized Japanese society during that time—even in the wake of its rapid technological advancement.

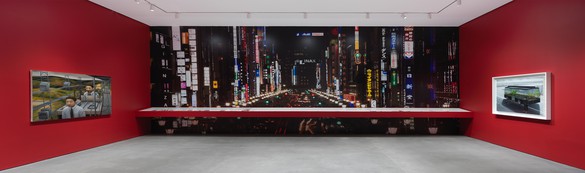

Cecilia Alemani inside the exhibition Tetsuya Ishida: My Anxious Self, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York, 2023. Artwork © Tetsuya Ishida Estate. Photo: Eleanor Gibson

In Conversation

Alexandra Munroe and Tomiko Yoda on Tetsuya Ishida

Moderated by Cecilia Alemani

Monday, October 2, 2023, 6:30pm

Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York

Join Gagosian for a conversation inside the exhibition My Anxious Self, the most comprehensive survey of paintings by the late Tetsuya Ishida (1973–2005) to have been staged outside of Japan, and the first-ever exhibition of his work in New York. Alexandra Munroe, senior curator at large, Global Arts, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation, will speak with Tomiko Yoda, Takashima Professor of Japanese Humanities at Harvard University, in a conversation moderated by exhibition curator Cecilia Alemani. The trio will discuss the societal context in which Ishida developed his work, the artist’s striking representations of the challenges of contemporary life, and his unflinching view of his contemporaries’ inward escape into highly consumable popular media.

Tetsuya Ishida, Prisoner, 1999 © Tetsuya Ishida Estate