Cecilia Alemani is a curator based in New York. Since 2011 she has been the Donald R. Mullen, Jr. Director & Chief Curator of High Line Art, the public-art program presented by the High Line, New York. In 2022 she curated The Milk of Dreams at the 59th Venice Biennale; in 2018 Alemani served as artistic director of the inaugural edition of Art Basel Cities, in Buenos Aires; and in 2017 she curated the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Over the past ten years Alemani has developed an expertise in commissioning and producing ambitious artworks for public and unusual spaces. Photo: Liz Ligon, courtesy The High Line

Alexandra Munroe is a scholar and curator of modern and contemporary Asian art and transnational art studies, and a leader of global arts strategy for museums. She is senior curator at large, Global Arts, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation, where she has led the museum’s Asian Art Initiative since its founding in 2006. From 2017 to 2023, as director of curatorial affairs for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Project, she supervised the team in New York and Abu Dhabi.

Tomiko Yoda is the Takashima Professor of Japanese Humanities in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University. Her specialization includes Japanese literature, media studies, and feminist studies. She is the author of Gender and National Literature: Heian Texts and the Constructions of Japanese Modernity (Duke University Press, 2004) and coeditor with Harry Harootunian of Japan after Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present (Duke University Press, 2006).

Cecilia AlemaniThis exhibition brings together more than eighty works by Tetsuya Ishida. I first saw Ishida’s work at the Venice Biennale in 2015, when Okwui Enwezor curated the exhibition and included him in the Central Pavilion. I’ve been a great admirer of his work since then.

Ishida was active from 1995 to 2005, so he had a very short career of just ten years, but the period when he was growing up in Tokyo was an extraordinary time. The 1990s have often been defined as the “lost decade” in Japan. It began with the burst of the economic bubble in 1991, which was followed by years of economic recession and stagnation. It also was marked by some very dramatic events, including the earthquake that struck Kobe in 1995, killing over six thousand people. That same year, Japan witnessed the awful terrorist attacks by Aum Shinrikyo in Tokyo’s subway.

Ishida was just twenty-two years old in 1995. I’m curious if you can describe what those years were like for him, growing up as a young man in in Japan.

Tomiko YodaI can’t claim to know Ishida’s experience of being young in the 1990s, but I would say that in the mid-1990s the full ramifications of the speculative bubble economy’s burst, which had inflated in the latter half of 1980s, were not fully grasped. Many were unsure whether this was merely a temporary dip in the business cycle or a sign of a fundamental societal shift.

Amidst this uncertainty, as you’ve mentioned, the Great Hanshin earthquake struck in January 1995, and only three months later Tokyo’s subway system was attacked with sarin gas by the religious cult group Aum Shinrikyo. Although these events were not directly related to the economic crisis, they melded in the public consciousness as a premonition of the hazards that the new millennium would bring.

[Ishida] was a product of the amazing movement in manga, in anime, and in film . . . this apocalyptic, existential fantasyland.

Alexandra Munroe

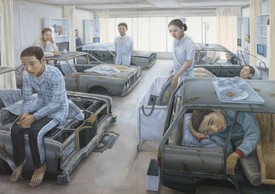

The difficulty in understanding the mid-1990s crises in Japan as they unfolded can be attributed to the prevailing social control system, the so-called enterprise society, which was underpinned by the close ties between domestic life, corporate workplaces, and formal education. This system was thought to be a uniquely Japanese version of capitalism, crystallized in the 1970s and intensified in the 1980s. It was seen as a constant throughout much of Japan’s postwar history, making it seem as if “Japan Inc.” had always existed and was here to stay. Imagining the future beyond it or an alternative to this formation was challenging. Looking at Ishida’s earlier work from the 1990s, I can’t help but perceive a powerful urge to critique this system, which, in hindsight, was beginning to crumble. There might be multiple temporalities at play in his work. He was undoubtedly channeling the unique anxiety of the mid-1990s. However, his point of reference might be heavily influenced by the enterprise society that solidified in the late 1970s. Additionally, I detect a sense of anticipated nostalgia for this era that was coming to a close.

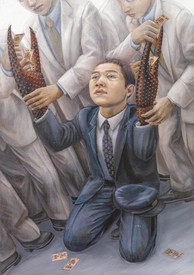

Take, for example, his painting of the lobster-clawed ticket master, featured on the cover of this exhibition’s catalogue [Gripe, 1996]. Ticket masters have become obsolete in Japan due to the introduction of automatic ticket gates in many urban stations during the 1990s, around the time Ishida created this piece. In the past, these men wielded ticket punchers like virtuosos playing musical instruments, and children were often captivated by their skill. While the ticket master in Ishida’s painting looks grotesque and desolate, forced to punch tickets with his claws, I wonder if there is a subtle nod to the pleasure or investment of desire that people had for the enterprise society and its strict form of discipline.

CAAlexandra, could you contextualize the art scene around Ishida in those years? From an art historical perspective, who were the artists Ishida was looking at, what was around him, and was there a major shift or change that you could identify in those years?

Alexandra MunroeI think part of what’s in these paintings, and part of what was in Takashi Murakami’s exhibition Little Boy [Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, curated by Murakami, 2005], is the huge suppression of the violence that had been perpetrated in World War II—both by the Japanese and against the Japanese—but had never had a historical resolution that could appear in textbooks and be taught to students born in 1973, like Ishida. There was an existential repositioning of a lot of Japanese intellectuals and artists during this time.

What I think is important to understand in Ishida’s case is that he was very independent. You asked, Who did he know? I don’t think he knew many artists. We have a comment that he made about Murakami, we have a comment that he made about [Yayoi] Kusama, both of whom were widely popular and well-known international figures by that time. But he really came out of an illustration background, out of otaku culture. He graduated from a very important art school [Musashino Art University, Tokyo], but from the design department, and not Geidai [Tokyo University of the Arts], where Murakami was, which is kind of the center of all things. When Murakami came into the gallery today, he said that he didn’t know Ishida in 2005 or he would have put him in Little Boy.

So I think the answer is more what Ishida was looking at in the culture. And there you have it in this exhibition. He was a product of the amazing movement in manga, in anime, and in film that produced the worlds of Evangelion, Doraemon, and Akira: this apocalyptic, existential fantasyland.

CATomiko, you talked about a clash of different temporalities as well as the idea of nostalgia. The 1990s saw renewed interest in apocalyptic literature from the 1970s; there was a very strong fear of the end of the world, and so books like Sakyo Komatsu’s Japan Sinks [1973] and Ben Goto’s Prophecies of Nostradamus [1973] became very popular. I don’t know if it was an influence on Ishida, but that sort of sentiment was embraced by manga and anime like Akira. I’m curious if you can help us understand how writers and artists and filmmakers were able to capture that sentiment, which hovers between nostalgia and this sort of proliferation of the apocalyptic, in books, in artworks, in films, in pop culture at large.

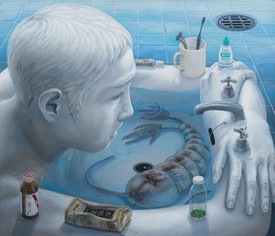

TYYes, the establishment of Japan Inc. in the 1970s coincided with an explosive development in media and consumer culture. I suspect that Ishida was an artist who worked in tension with both enterprise society and this extremely permissive media culture of Japan, rife with sex, violence, and the grotesque. He grappled with the question of how to intervene in this situation as an artist, and an independent one at that.

Returning to your reference to Akira and the apocalyptic imagination, postwar Japan has consistently invoked images of cataclysm, as seen in the long series of Godzilla films that began in the 1950s. The prevalence of catastrophe in the Japanese cultural imagination undoubtedly ties back to wartime experiences, including the atomic bomb. However, each generation has reimagined the narrative of the cataclysm under evolving historical conditions. For instance, the novel Japan Sinks responded to the end of the period of high-speed economic growth and the uncertainty of Japan’s future. As for the 1980s, the original manga and film adaptation of Akira serve as a prime example; the fictional Neo-Tokyo where Akira is set was constructed after World War III, if my memory serves me right.

CAYes, I think a mysterious explosion in 1982 destroys Tokyo completely and the city is then rebuilt as Neo-Tokyo.

TYRight, right. And yet the world it portrays is a postmodern, 1980s-style “sampling” of cultural references from the early postwar era, the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, and youth subcultures from the 1970s and 1980s. Fast-forward to 1995, the year when the groundbreaking anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion first aired: Ishida was a fan of the series, which is set in Tokyo-3. This isn’t a neo- or reconstructed Tokyo, but a decoy city built atop a vast cavern housing a massive military installation designed to combat an anticipated enemy known as the Angels. But the identities of those behind this military complex and the nature of the Angels remain unclear. The Angels appear in various forms, sometimes biological, sometimes purely psychic, and at other times they are mechanical robots or weapons. How does one prepare for such an enemy?

I suspect that Ishida was an artist who worked in tension with both enterprise society and this extremely permissive media culture of Japan, rife with sex, violence, and the grotesque.

Tomiko Yoda

There are hints of past catastrophes and expectations of future ones, but the series is riddled with mysteries that are barely resolved. Meanwhile, the adolescent protagonists, when not battling the Angels, lead lives that closely mirror the everyday experiences of teenagers in Japan in the mid-1990s. Evangelion was conceived before 1995, but many critics and viewers at the time were struck by how well it synchronized with the zeitgeist of the moment—a strange coexistence of crisis and the ordinary or “endless” everyday. It felt as though a significant game-changer was imminent, unfolding, or had already occurred, yet life continued with deceptive banality.

CAAlexandra, tell us about Little Boy. You worked with Murakami on this exhibition, which captured postwar pop culture in Japan. It was not only about kawaii and Superflat; it really dealt with the existential crisis of the Japanese culture after World War II. Can you talk about it a little?

AMAs I’m looking at these paintings by Ishida, I see a lot of ambiguity in the work; there is something floating, a miasma. I think that brings us to what Little Boy was. This was a major exhibition presented at the Japan Society in New York. I had approached Takashi and asked him to give me the pulse of his country. I knew he had been thinking and writing about postwar Japan and said, Let’s do a show about that.

I think it is absolutely Takashi’s most brilliant curatorial feat to this day. What he did was to look at all the toys that someone like Ishida would have grown up with, all of the movies and anime and manga and comics that Ishida was reading, and to look at their makers, their creators, going back to Godzilla, which came out in 1954. Godzilla was the first tokusatsu monster film that was a remaking, a reliving also, of the destruction of Tokyo: Godzilla comes and burns down Tokyo overnight. This was nine years after the real firebombing of Tokyo, in March 1945, so for those watching the film, it was absolutely traumatic.

Murakami’s thesis in that exhibition was that these monster games, anime, manga—it’s all infantilized, right? It’s as if the history of Japan’s war becomes submerged in what he calls the collective subjugation of being an infantilized partner to the US. There’s that famous photograph, taken in the days after Japan’s surrender, depicting the emperor in a morning coat and General MacArthur towering over him in military fatigue with an open collar. That photograph, Murakami says, becomes emblematic of the highly imbalanced relationship defining not only the US–Japanese relationship, but also Japanese self-identity. This lasted beyond the immediate, official occupation period and into what became an occupied Japan. Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, drafted under the US occupation, forces Japan to give up its military. And Murakami is asking—in what can be construed as a very right-wing, pro-emperor, pro-military position—How can we be a man if we can’t arm ourselves? We’re being armed by the US, so it’s Daddy who’s taking care of us. We have been in this infantilized position and therefore our imagination of violence and apocalypse, our guilt such that it is, our psychic ability to process that, not only of being a victim but of victimizing others, has had to be sublimated into kids’ toys. And that’s where, he says, all this violence comes out in the imagination of Sunday cartoon shows like Time Bokan. Growing up in Japan, I watched Time Bokan, too, and at the end of every cartoon the world blows up, in what? A mushroom cloud. But next Sunday we come back and everything’s happy again. It’s like looking at Grimm’s fairytales and realizing, Shit, these are really fucked up. [Laughter.] Murakami was the one to look at all of this and give it a thesis from an artist’s point of view.

He was also very interested in breaking down the barriers between high art and popular culture—I mean, art that’s shown at Gagosian and art that’s sold in, you know, a Canal Street arcade. He showed artists from his own Kaikai Kiki group, many of whom have gone on to have careers of their own, and others, like Izumi Kato, whose work he was showing for the first time and who didn’t yet have international reputations—artists like that side by side with, you know, a room of tin and plastic toys from the postwar period, with Hello Kitty and Godzilla and all that.

CATomiko, I want to switch gears and ask you something about the subjects of the paintings in My Anxious Self. Usually, the main character in Ishida’s work is a young boy, a recurring figure, almost like an alter ego. Many people asked Ishida whether these were self-portraits, and in the end he said that they were not his self-portraits but self-portraits of others, which I think is a beautiful way of talking about this idea of seriality and collectivity.

There are very few women in Ishida’s paintings, but there is a room at the end of the show where I tried to gather most of the pictures—mostly made during his last five years of production—that depict women and children and young babies, as though he was reflecting on ideas of maternity and childhood. What do you think about this shift in his practice?

TYWell, first of all the “character” in contemporary Japanese pop culture is a loaded term. In anime, manga, and video games, the term “kyara,” a shortened form of “character,” gained popularity during the 1990s. By the early 2000s, Azuma Hiroki, an influential critic (who has collaborated with Murakami), suggested that while the first-generation otaku culture of the 1970s and 1980s was heavily invested in world-building, by the mid-1990s the focus of otaku culture had shifted to kyara and fans’ affective responses to kyara. Roughly speaking, while characters are often at the center of narrative actions and events and serve the story and its themes, kyara are endowed with appealing visuals and other attributes that grab fan interest. They can be abstracted from stories and thus traverse and link multiple story worlds and media platforms, serving as a conduit for frenetic, multiplatform marketing strategies and modes of consumption.

The recurring image of similar-looking male figures appearing against unrelated and sometimes surreal backgrounds in Ishida’s art might be considered a form of kyara. However, Ishida’s characters don’t resemble popular anime or manga characters of the 1990s. They are more evocative of figures drawn by Rokuro Taniuchi, known for his lyrical, “Showa nostalgic” illustrations, or characters drawn by Yoshiharu Tsuge, a leading artist of the 1960s and 1970s experimental manga scene. Additionally, in the 1990s the characters that proliferated across multiple media platforms tended to be cute “anime girls.” By choosing to draw mostly masculine figures, with specific facial and physical features, Ishida may have been both drawing from and resisting contemporary trends in pop culture.

On the topic of gender, it’s worth noting that the 1990s was a decade in which the declining fertility rate was perceived to be reaching a crisis point. There were also worries about the sustainability of social reproduction, evidenced by a series of moral panics about youths. High-profile news reports of young boys committing violent crimes surged. Meanwhile, teenage girls were said to be indifferent to existing sexual norms, commodifying their bodies, and engaging in transactional “dating” with older men. By the late 1990s, the structural dysfunction of the sexual contract under the enterprise society was becoming increasingly palpable, and there was much discussion about female malaise—self-harming behaviors, mental health issues, and a general sense of “unlivableness” felt by women.

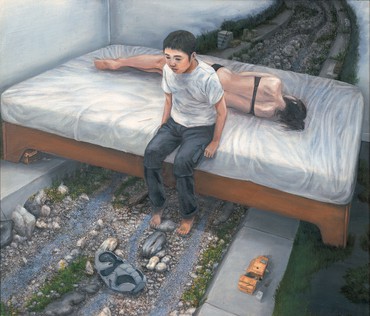

In contrast to his earlier work, Ishida’s later paintings feature some striking images of women. For instance, the painting titled Abortion [2004] not only depicts the familiar male character sitting on a bed but also a woman lying behind him, facing away. Dressed scantily, her thin body appears vulnerable and distressed, although her facial expression is hidden. There is much to discuss in this painting, including the dry riverbed under the bed and the tiny infant’s body on the ground, almost indistinguishable from the surrounding rocks. At any rate, the images of women mark a significant thematic shift in Ishida’s later paintings, where we also repeatedly see strange or grotesque processes of reproduction. These images may have been inspired by Ishida’s personal experiences during this period, but they also seem to echo the profound anxiety about the conditions of women and sociobiological reproduction in late 1990s Japan.

CAWhat do you think about it, Alexandra?

AMI would agree. There were pronouncements at that time that Japan would disappear—that by the year 2300 or so, there would be no people left. It was kind of apocalyptic in a different way, a very slow decline into nothing.

In terms of gender depictions, I think we also must look at what was going on in literature at this time, which I’m assuming Ishida was reading. It’s this period of Haruki Murakami, Banana Yoshimoto—they were writing about pretty weird stuff too. And Ishida loved Kobo Abe, who was talking about women in very subjugated roles that were both idealized and totally dehumanized. You see it in the films of the period as well. Actually, what’s interesting is that it’s only in some of the manga anime films where women become weaponized and begin to have superpowers. You didn’t have that in the popular culture prior to that at all.

What we haven’t spoken about is that this was also very much about consumer capitalism and its deadpan, mechanistic vapidness. What was happening on the streets of Tokyo at this time, as a result of the high-growth economic period of the 1980s, was that the city was being rebuilt. Postwar Tokyo still didn’t have many high-rise buildings. And this is when Japanese architects were rising; it’s the period of [Arata] Isozaki, [Fumihiko] Maki, [Tadao] Ando, and others. All the subway stations were completely rebuilt. A lot of it was built in a rush, at a very fast pace.

And in the midst of this rapidly changing cityscape and the new suburbs of Tokyo, you have the twenty-four-hour konbini store, with its horrible glaring neon lights. The streets, even of traditional towns like Kyoto, are now littered with jidohanbaiki, vending machines, where you can buy everything—everything becomes a can.

I’m struck by how many of Ishida’s paintings illustrate that konbini-store kind of existential nihilism. And again, I just quote Murakami, “Safe and sound, hysteria.” [Laughter.]

Tetsuya Ishida: My Anxious Self, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York, September 12–October 21, 2023

Artwork © Tetsuya Ishida Estate