Cecilia Alemani is a curator based in New York. Since 2011 she has been the Donald R. Mullen, Jr. Director & Chief Curator of High Line Art, the public-art program presented by the High Line, New York. In 2022 she curated The Milk of Dreams at the 59th Venice Biennale; in 2018 Alemani served as artistic director of the inaugural edition of Art Basel Cities, in Buenos Aires; and in 2017 she curated the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Over the past ten years Alemani has developed an expertise in commissioning and producing ambitious artworks for public and unusual spaces. Photo: Liz Ligon, courtesy The High Line

Japan: The Lost Decade

Over the course of a ten-year career cut short by his premature death in 2005, Tetsuya Ishida made over two hundred paintings that perfectly capture, in his iconic, fantastic, Surrealist style, the anxieties and trauma that he shared with countless young Japanese people who reached adulthood in the 1990s, during the country’s “Lost Decade.” In 1991, Japan’s bubble economy burst, ending a period of rapid economic growth that had begun after World War II and was characterized by cooperation among manufacturers, suppliers, distributors, and banks; good relations between business and government; the promise of lifetime employment in big corporations; and highly unionized blue-collar factories. Ishida started painting in 1995, at the height of the economic stagnation, when Japan was also shaken by major traumatic events such as the Kobe earthquake in January 1995, which killed more than 6,000 people; the sarin-gas attacks in Tokyo’s subway system by members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult two months later, in which thirteen people died and more than 5,800 were injured; and the beheading of two children by a fourteen-year-old at Tainohata Elementary School in Kobe in 1997. But he also grew up witnessing the unthinkable advancement of technology, with the launch of Windows 95, which contributed to the widespread popularization of computers; cellular phones and new gaming consoles flooding the market; and computer-controlled robots being introduced to the manufacturing process, replacing assembly-line workers.

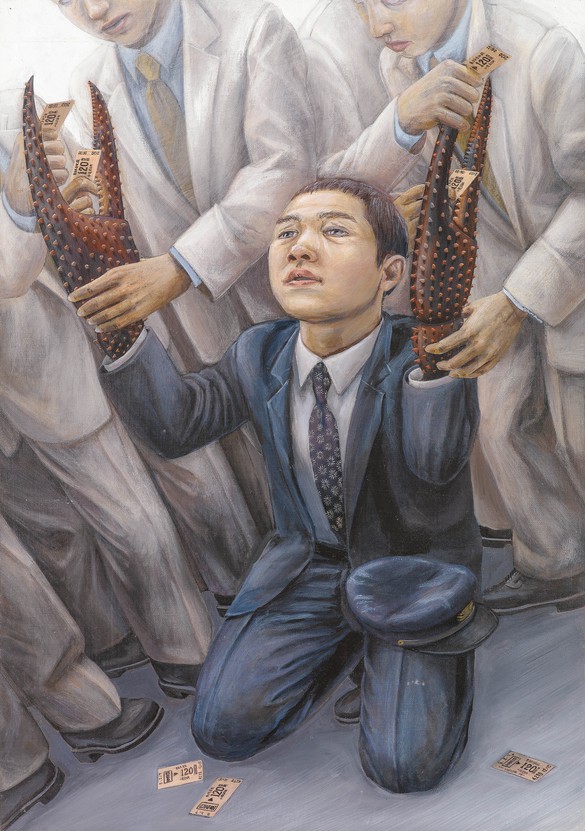

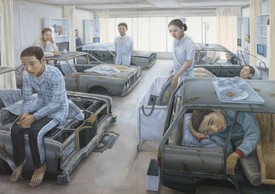

Ishida’s eerie portraits of young men condense the drama and isolation that defined the Lost Decade, when unemployment rates almost tripled and temporary employment rose to 21.8 percent in 1999 (from 10 percent in 1980).1 Those who came of age during this period are described as the “Lost Generation.” Many young adults were unable to find full-time jobs and had to turn to temporary and low-paid roles, or did not work at all. A different affective constellation emerged: “a sense of displacement, ungroundedness, and loneliness that gets captured in what circulate[d] as a slogan of the times—‘without a place to call home’ (ibasho ga nai).”2 During this time, also referred to as the “Employment Ice Age,” Ishida decided to become a painter, and he permeated his compositions with the existential distress of his generation. He was an introverted young man who supported himself by working part-time as a laborer in a print shop or as a night security guard. His entire income went toward art supplies.

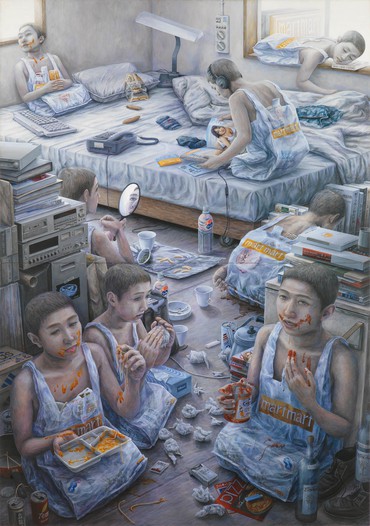

In the 1990s, multitudes of young people in Japan withdrew from society, becoming recluses known as hikikomori.3 These were unemployed young individuals, mostly male, who isolated themselves from social relationships, often not leaving their bedrooms and fully depending on their parents.4 In many of Ishida’s compositions, socially withdrawn young men are depicted in interior spaces, frequently accompanied by nascent technologies such as computers and cell phones—which, with access to the World Wide Web, provided a way to maintain a view onto the outside world while remaining shielded by anonymity.

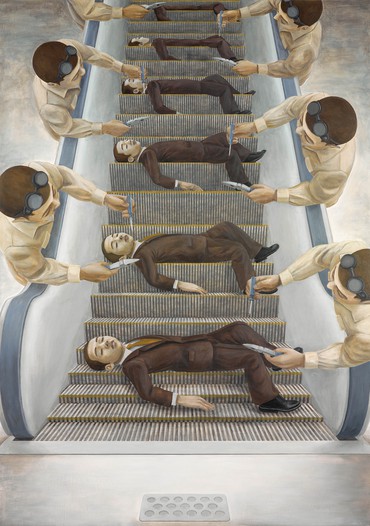

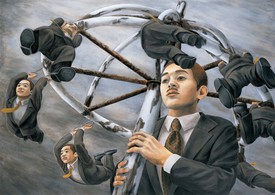

As Japanese companies tried to restructure during the recession, workers who managed to be employed often had to work an exhausting seventy or more hours per week, under a great deal of pressure. The expressionless, short-haired individuals wearing suits and ties that appear frequently in Ishida’s early works represent the sararimen (salarymen), white-collar male office workers who worked like robots for very long hours, identifying with the corporate collectivity to the point of losing their own subjectivity. In Ishida’s paintings, they are repeatedly portrayed in assembly lines as though they are the products they are making, never smiling, all with the same lost gaze, on the verge of automation. They assemble things, they eat their lunch, they are interviewed, they shop. Anonymous in appearance, they conduct all these quotidian activities with the passivity of pure work alienation. They embody a sense of estrangement and rupture that was so common in Japan after the economic bubble burst and that often culminated in karoushi, sudden death by overwork, or karoujisatsu, death by suicide due to overwork, both of which became devastating social issues in the late 1980s and peaked in the 1990s.5 Early paintings by Ishida capture the post-productive, post-labor landscape that emerged during that decade and the alienating and isolating effects of Japan’s regulated society, torn between overwork and the numbness of daily life, collectivity and isolation. They depict both the psychological wounds experienced by many and the artist’s own struggles with anxiety, emptiness, and a precarious livelihood.

Early Life and Lucky Dragon

Ishida was born in the city of Yaizu, in Shizuoka Prefecture, in 1973, the youngest of four children from a middle-class family. His father, a tax accountant who served as a member of the municipal assembly of Yaizu for more than ten years, did not spend a lot of time at home, but he talked about the social situation and difficult realities at dinner with his family. Ishida’s mother worked for Shizuoka’s prefectural government, which, for a woman, was quite rare at the time. As a boy, Ishida was meticulous and well prepared. His brothers would make fun of him, saying, “You’ve done everything and now you have nothing to do but sleep.”6 From a very young age, Ishida demonstrated a propensity for art.

In 1981, when Ishida was eight years old, he read a book, Hey White Boat (Hey Masshirobune,) about the fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon no. 5). In early 1954, the Lucky Dragon had left the port of Yaizu for an ocean voyage, and on March 1 was caught in the nuclear cloud generated by the hydrogen-bomb test named Castle Bravo, conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Despite being outside the official danger zone, the boat was heavily contaminated by the fallout. The twenty-three crew members on board all developed severe and long-lasting symptoms of radiation poisoning, which led to the death of one, radio operator Aikichi Kuboyama. This dramatic event resonated internationally. Moved by the injustice of the accident, American painter Ben Shahn was outspoken in advocating against nuclear testing and armament. In early 1958, a series of prints by Shahn was published in Harper’s Magazine to accompany a report on the incident by the American nuclear physicist Dr. Ralph E. Lapp, and in the years that followed he made a series of works on the subject in which he merged his style with motifs from Japanese artistic traditions. These works are a vivid testament to the nuclear anxieties that defined the Cold War period. In 1996, Ishida visited an exhibition in Tokyo, Lucky Dragon: Projection on a Hill, a show of Shahn’s illustrations and paintings dedicated to the fishing boat. The visit would greatly influence his future career.

In the same year that he read Hey White Boat, Ishida submitted an essay to a contest held in Yaizu. Its title, “Mr. White Boat” (“Masshirofuneken”), referred to the Lucky Dragon, and in it he wrote, “From there, the entire body became sick and suffered. The nuclear testing caused hair to fall out and blood loss. They were in pain and could not get up to go to work. It’s really a tragedy. Why would humans use H-bombs to kill each other?”7

A Kind of Social Surrealism

From a young age, Ishida was very active in school and demonstrated a profound interest in portraying the injustices that surrounded him. When he was eleven years old, he designed his class flag and, in a contest held by the Shizuoka District Legal Affairs Bureau, received first prize for an illustration, Stop Bullying Weaklings! (1984). This could be seen as the beginning of his deep interest in a socially engaged approach to art. He later wrote in his diary, “I wanted to be like Ben Shahn. Looking back, I may have won first prize for the human rights poster because it was in the style of Ben Shahn.”8

From the early stages of his career, Ishida’s style fused the art-historical genealogies of realism and Surrealism. If realism emerged during the industrialization of the nineteenth century and aimed at depicting the harsh reality of that time, Surrealism, which developed between the two world wars, amid the rapid mechanization of the early twentieth century, fed the imagination and the unconscious an antidote to a world lost to reason and alienation. Ishida leveraged the acute observational skills associated with realism to bear witness to the existential and societal crises brought about by Japan’s Lost Decade, while simultaneously incorporating Surrealism’s use of metamorphosis, the uncanny, and the fantastic, assuming that reality is far more absurd and bizarre than its depiction.

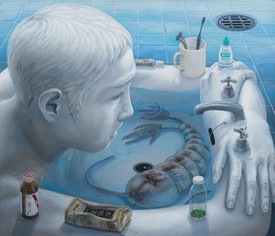

Ishida’s blending of realism with Surrealism to depict human vulnerability, estrangement, and claustrophobia has fewer affinities with the work of his contemporaries than with that of a group of postwar Japanese artists working in realism who, by the end of the 1950s, had started to use a surreal approach: the Seisakusha Kondankai (Creators’ discussion group), whose members were Tatsuo Ikeda, Shigeo Ishii, and On Kawara. Each of these artists, in his own way, imagined a new kind of realism far from the strictures of the Socialist Realism that was encouraged and supported by the Japanese Communist Party, opening up instead to Surrealism, through which they could process the atrocity of the contemporary world—for instance, the aftermath of World War II and nuclear proliferation—by embracing the imagination.9 Of works by Kawarak, Ishida admired the early Bathroom series (1953–54), black-and-white works depicting dismembered and mutating bodies in gloomy, tiled bathrooms, rendered through a distorted perspective—perhaps a nod and reaction to Tokyo’s Socialist Realist painters. Ikeda, too, created surreal scenes in delicate drawings that represent transfigured bodies immersed in organic shapes and swirling backgrounds as an ode to pacifist political ideals. As part of his Anti-Atomic Bomb series (1954), Ikeda also made works about the Lucky Dragon tragedy, one of which shows a grotesque and toxic catch of fish that is almost anthropomorphic. Works by Neo-Dada artists such as Tetsumi Kudo and Shusaku Arakawa shared the same suffocating air of death and postapocalyptic alienation.

Realism, Surrealism, and social critique were certainly approaches that intrigued Ishida more than what surrounded him in mass culture and contemporary art in Japan, which could be characterized by the kawaii (cute) aesthetic, as well as a refusal to engage with the grim social situation. Japanese artists in the 1990s were mostly seduced by kawaiimono (cute things), as well as by manga and anime, as seen in the Neo-Pop and Superflat tendencies of the likes of Takashi Murakami, Yayoi Kusama, and Yoshimoto Nara. Unlike many of his colleagues or more established artists active at the same time, Ishida described with systematic attention the everyday life around him and the existential condition of many of his peers. His was a lonely voice as he dedicated his life to painting in a realistic manner coupled with a fantastical approach. In a 2000 notebook entry, he wrote, “I believe that my self-portrait paintings have the function of letting the viewer look around at the contemporary world, society, and values.”10

Today, Ishida’s work speaks acutely to the new habits spread by the outbreak of the covid-19 pandemic and its enforced seclusion, as well as to the growing loneliness that it brought and—in the words of philosopher Byung-Chul Han—the society of tiredness and fatigue wrought by the rise of digital technological developments in neoliberal capitalism, which have transformed the disciplinary society into an achievement society, exacerbating our sense of overload and burnout. Ishida’s absurdist universe—filled with exhausted, apathetic, numb, gloomy, and depressed individuals—is not unlike the burnout society that Han describes, which arises from the contradiction between the desire for freedom and the pressure to conform to social norms and expectations, as well as the imperative to perform, produce, and achieve.

Ishida’s art calls for a greater emphasis on community and human connection, and for a revaluation of our values and priorities as a society. Though his career was cut short by a tragic incident when he was only thirty-one, Ishida’s legacy endures, his works inspiring us to reflect on the challenges we face and to seek meaning and connection in a world that often feels absurd and alienating. Through an impressively extended production concentrated in only ten years, Ishida not only captured the youth of his era, but also anticipated many of the anxieties and the preoccupations that are defining young generations globally. Ishida felt compelled to continue painting “people at the mercy of the contradictory nature of Japan’s social systems for as long as they exist.”11 His restless dream that art could highlight the social contradictions of our time resonates today more than ever.

1See Koji Morioka, “Causes and Consequences of the Japanese Depression of the 1990s,” International Journal of Political Economy 29, no. 1 (1999), p. 21.

2Anne Allison, “Ordinary Refugees: Social Precarity and Soul in 21st Century Japan,” Anthropological Quarterly 85, no. 2 (2012), p. 351.

3A term coined in the 1990s, from the verb hiki (“to withdraw”) and komori (“to be inside”).

4In 2000, estimates of the number of hikikomori in Japan ranged from 50,000 to 1 million. See Tim Larimer, “Natural-Born Killers?,” Time, August 28, 2000. Available online at https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,997801,00.html (accessed June 21, 2023).

5By 1998, the number of suicides in Japan due to overwork, financial difficulties, or unemployment had exceeded 30,000 annually. See Allison, “Ordinary Refugees,” p. 346.

6See “Tetsuya Ishida’s Chronology,” in Tetsuya Ishida: Self-Portrait of Other, exh. guide (Chicago: Wrightwood 659, 2019), p. 3.

7Ishida, quoted in Yuzo Ueda, “The Life and Times of Tetsuya Ishida: Confession and Spirit,” in Tetsuya Ishida (Hong Kong: Gagosian Gallery, 2014), p. 65.

8Ishida, quoted in Masato Horikiri, “Tetsuya Ishida and His Times,” in Tetsuya Ishida—Complete, 4th ed. (Tokyo: Kyuryudo, 2021), p. 11. One of Ishida’s very early drawings, Parking Lot Drama (1994), shares a style similar to Shahn’s.

9See Doryun Chong, “Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde,” in Chong, Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), pp. 37–38.

10Ishida, notebook entry, 2000, quoted in Horikiri, “Tetsuya Ishida and His Times,” p. 13.

11Ishida, in a clip from an archival TV Tokyo television interview included in an episode of the television program Kirin Art Gallery: Grand Masters of Art (Bi No Kyojintachi) broadcast on TV Tokyo on April 26, 2008.

Tetsuya Ishida: My Anxious Self, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York, September 12–October 21, 2023

Artwork © Tetsuya Ishida Estate