Working at the Centre Pompidou with Christine Macel, Alicia Knock explores new exhibition and working formats, even questioning the museum itself (Museum On/Off, 2016). She is currently working on expanding the museum’s perspectives toward West Africa and Central Europe, through both acquisitions and exhibitions.

Alicia KnockHarmony, you’ve been playing with the scales, forms, and textures of images for years. Can you talk about your creative process and your interest in the “translation” of images—how images are repeated, rephotographed, photocopied, endlessly looped?

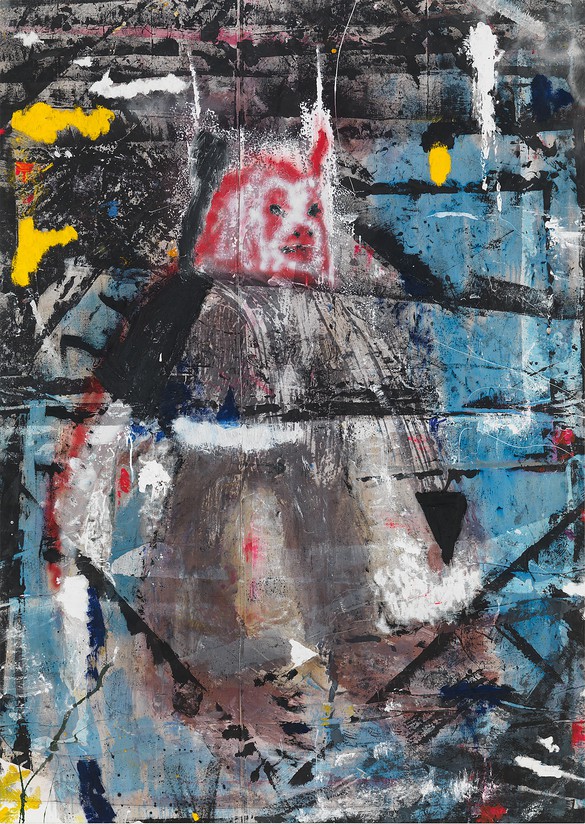

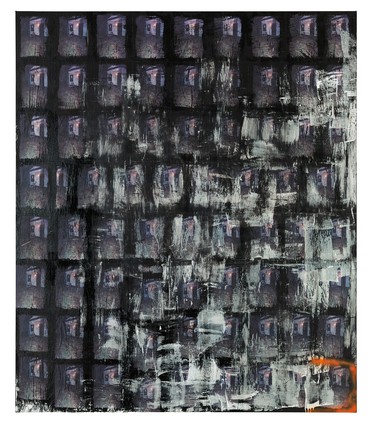

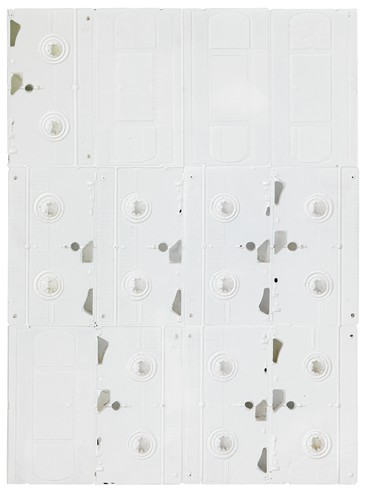

Harmony KorineI’ve always liked the idea of loops and repetition. To break images down and bring them back up again—to deconstruct imagery and then reconstruct it. . . . I’ve photographed TV screens, filmed projections of my movies, photocopied my drawings, rephotographed stuff. When I make paintings I often work in series. There’s something hallucinatory about loop-based repetition. It can even approximate something hypnotic and physical, almost like a drug experience. A lot of my films and artwork share that sense of looping.

AKIt feels like you’re searching for the essence of the images, chasing the ghosts hidden behind them. The figurative and the abstract meet in your paintings; the positive side of the image and its shadow are often mirrored.

HKYes, I’m interested in reaching under the image into the soul. Sometimes when you strip something you just keep stripping it, stripping it, stripping it, until you reveal its core. That can be haunting and powerful.

AKPart of your imagery deals with underground America and the margins of society: freaks evolving in desolate landscapes, in the lonely parking lots you would skateboard in as a kid. Do you feel like you belong to an American counterculture?

HKI definitely belong to American culture; counterculture, I don’t know. I’m from it, I grew up in it, but I’m not of it. My work isn’t really a reflection, it’s more of a feeling, it has a vibe. But there’s definitely an American vernacular that I saw growing up: alleyways, dilapidated buildings, the backs of supermarkets, and other American ruins that I find irresistibly attractive.

AKIn many ways, particularly because of your unified aesthetic and your interest in both social realities and inner visions, you can be considered a romantic artist like Victor Hugo, who was a relentless experimenter and a poet fascinated by politics and ghosts. Do you feel as though you belong to that tradition?

HKSure. I’ve always seen art as everything and I never wanted to limit myself to one specific medium. Some ideas come to you in the form of writing, some in the form of painting, film, sound. I never question, I usually just try to act on urges, and I don’t differentiate between high and low. Forms are like musical instruments. It’s fun to see everything brought together in the exhibition though. Thirty years of work since high school! In that type of context you can see more fully how things relate to each other. It’s revealing.

AKThe collage aspect and broken narratives in your work paradoxically lead the viewer to experience an ongoing phenomenon, that of the haunting image. Everything looks fragmented but in the end there’s a constant backbone behind it all.

HKI never really think about where it comes from; since I was little I’ve always just acted on impulse. When I was young I loved joke books, books of quotations, riddles, rumors, myths. I was never attracted to long form, I usually try to simplify. I always wanted to write novels where pages are missing in all the right places. I think the undefined is always powerful. To me, art, whether conscious or not, always involves leaving the margins undefined. It lies in what’s not said or what’s missing. Whether it’s the scripts or the paintings, when I’m done, most of the time I look at them and they often look too literal, or they make too much sense. That makes me wonder, what if I pull this paragraph away, what if I have this story shift, what if. . . .I used to play games with myself: I would read an interview in a magazine with someone like Clint Eastwood and I would imagine the same interview except I’d think, What if it was said by Snoop Dogg. Then I would reread it and it would be hilarious. I’ve always loved the shift of an idea, changing who’s saying what, who’s making what. A lot of my early fanzines did that, replacing words. In high school I was so bored I would just play games with myself—personal jokes, and that must have transferred into the work.

I think the undefined is always powerful. To me, art, whether conscious or not, always involves leaving the margins undefined. It lies in what’s not said or what’s missing.

Harmony Korine

AKMistakes and failure have always played a role in your aesthetic. Do you consider failure a leitmotif?

HKI used to call that “mistake-ism.” The idea of the mistake or accident is often the most interesting part. Before making something, the false steps, the misspellings or the malapropisms, tend to be exciting to me. You always hear people shying away from mistakes, but they’re what’s most revealing. When I say “mistakes,” I mean the things that are the most awkward, or that were done with the least amount of forethought. It’s the things people want to change, to edit or autocorrect, but that dulls the edges. In the end the work is perfect, it’s meant to be the way it is. The mistakes are like a coded logic or an internal vernacular.

I’ve always loved when people would invent their own language. Mark Gonzales is a good example of that. I love his poetry—all his misspellings, how the text transforms and opens up to multiple meanings.

AKYou came to art through friendships with artists you worked with: Rita Ackermann, Christopher Wool, Josh Smith, and others. Can you talk about those collaborations?

HKThey were just like anything else, being in the proximity of friends. It was organic, and usually came out of the desire to find ways to cause trouble together. Somebody would draw something and then you would draw on top of it and that was it. Just like riffing together. It was the spirit of the time, though I guess now things have changed and become more and more marketed within the art world.

AKIt seems like it was all about building a community. That was also how you started collecting artworks.

HKWhen I was a kid I met Larry Clark and moved into his house for a year. He was the first person I saw who actually lived with artwork, he had a great collection. And I loved living with art. The same thing happened when I would hang with Christopher Wool, I would see all the art and books, it was exciting to be around, and I loved the energy. At that point, even as a kid, whenever I had extra money I would buy artwork. Mostly from friends.

AKCan you talk about your visual references, specifically those not directly related to the contemporary art world? You often talk about Southern folk artists, or, for instance, that fisherman/painter from Texas, Forrest Bess, who was recently rediscovered.

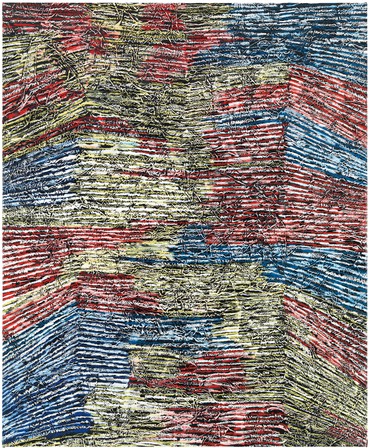

HKGrowing up in the South, black vernacular artists were my favorite. I just always love visionary art and painting, more based in the soul or things that are inexplicable. I always have problems with work you can define too easily. When I was growing up, artists like Thornton Dial, J. B. Murray, Purvis Young, those guys, were my heroes. Just the way they would create things, painting on whatever was around: trash, trees, sticks, signage. The immediacy and the strangeness of it, the world that you would create. Also a lot of it had visionary, quasi-religious connotations. The art that I love has this transference, speaking to a kind of god.

AKYou often say you don’t remember how your paintings were made, as if you were a mediator of some unknown force. Your work has to do with parallel worlds and even the sacred.

HKThe sacred and the blasphemous, it’s all interconnected. I always try to make things that aren’t earthbound. The work becomes about transcendence. In the films and artwork there’s this kind of magical realism: it’s like the real world but pushed into something hyperextreme.

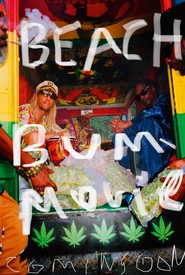

Artwork © Harmony Korine; photos: Rob McKeever