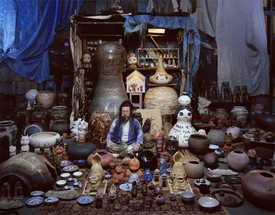

Takashi Murakami earned a PhD from the Tokyo University of the Arts Graduate School of Fine Arts. He began exhibiting his work while still at the university and in 1996 established the Hiropon Factory studio (today Kaikai Kiki) to produce it. In addition to making and marketing Murakami’s art and related work, Kaikai Kiki functions as a supportive environment for fostering emerging artists. With the curation of the 2000 Superflat exhibition, Murakami advanced the Superflat theory of Japanese art. He has exhibited widely both in Japan and overseas. Photo: Claire Dorn

Art historian Nobuo Tsuji is a professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo and Tama Art University. His book Kisō no keifu (Lineage of Eccentrics), from 1970, was a trailblazing reappraisal of “eccentric artists” such as Iwasa Matabei, Kanō Sansetsu, Itō Jackuchū, Soga Shōhaku, and Utagawa Kuniyoshi, and dramatically changed the popular view of early modern Japanese art. Tsuji views decorativeness, playfulness, and animism as quintessential features of Japanese art. He has written on a wide range of subjects, from decorative crafts to paintings depicting ghosts, erotic art, and manga.

The Kaikai Kiki of Soga Shōhaku

Text by Nobuo Tsuji

Murakami-san says “Itō Jakuchū is great, but Soga Shōhaku is more my style.” This time, let us look at a couple of works by Shōhaku.

Shōhaku (1730–1781), a contemporary of Jakuchū, was born into a Kyoto merchant family. He was born fourteen years after Jakuchū but died about twenty years before him, at the age of fifty-one. Shōhaku could not compete with Jakuchū in terms of longevity, but they were both great talents who freely expressed their powerful and distinctive vision in the open-minded artistic environment that prevailed in Kyoto at the time.

Little is known about Shōhaku’s family, but he is said to have been the son of a dyer. Four years before his death, when his young son died, he erected a tomb at the temple Kōshōji in Kyoto for his entire family, including himself. In 1967, when I located these graves with prewar records as my guide, the stones were heavily eroded and crumbling away. I took some emergency measures to patch them up, but I wonder what condition they are in today.

Based on the gravestone inscriptions and historical records, I was able to determine that Shōhaku had lost his older brother when he was eleven, his father when he was fourteen, and his mother when he was seventeen. This must have put an end to the family business. It is likely no coincidence that he decided to become a painter around this time.

However, Shōhaku’s early paintings seem too bizarre to be the work of a professional in the making. His folding screen Pang Jushi (Hōkoji) and Ling Zhaonu (Reishōjo): Parody of Jiumei (Kume) the Transcendent (1759), painted when he was thirty years old, is a perfect example. It shows a scene from the story of an immortal called Kume, related in the Konjaku monogatari shū. Having gained the power of flight, Kume was soaring above Mount Yoshino when he looked down and saw a young woman with her kimono rolled up as she washed clothes in the river. The sight of her white legs caused him to lose his magical powers and crash down to earth, where he ended up marrying the woman and living with her.

In the middle stands a gnarled old oak tree, which looks as if it were about to start walking like something out of a Disney cartoon. In the hut on the right side is the aged Kume, weaving a bamboo basket like a Buddhist penitent in an old Chinese folktale. His gaze wanders over to the left side of the picture, where the woman from the story sits, doing laundry in the river with her legs bared just like when he first spotted her. While the picture appears to be poking fun at the old man’s lecherous obsession, the style has a touch of the bizarre (kaikai kiki). The painting is much more eccentric than the work of Takada Keiho (1674–1755), the teacher who influenced Shōhaku.

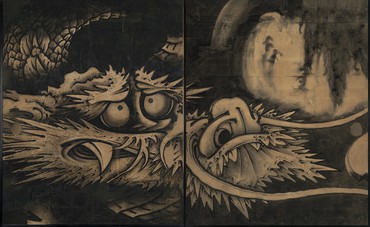

Starting around this time, Shōhaku often traveled to Ise and Banshū (present-day southwestern Hyōgo Prefecture). The Meiji-era painter Hashimoto Kansetsu (1883–1945) related that during his youth (presumably his late teens, after his father moved to Banshū, around 1900), when he was traveling around Takasago, there was a temple in the village of Ihozaki famous for a large dragon painted on sliding doors by Soga Shōhaku. It was said to be a fearsome painting, “the doors painted almost completely pitch black,” which the faint of heart were unable to view on their own. “From a background splashed with black ink representing pouring rain and thunderclouds, two incredibly lifelike dragons rear out, as if about to emerge from the painting and ravage the village,” Kansetsu wrote. “I hear that afterward, the painting was purchased by a man from Osaka.”1 When Dragon and Clouds, the work believed to be this painting peeled off of the sliding doors, was discovered in storage at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, I was just about finished writing my book Lineage of Eccentrics, and I rushed to have the publishers add it to the book’s illustrations.

When I saw this monumental painting in Boston, it had been put on thick paper backing, and what had originally taken up eight sliding doors was now on four horizontally elongated panels. It was inscribed “Painted at thirty-four years of age.” The word “sublime” did not do it justice, it was mind-bogglingly stupendous. Apparently it was one of the most prized works in the collection of William Sturgis Bigelow (1850–1926) and was not to leave the museum. At the time, it had never been back to Japan since he acquired it.

A few years ago, the Japanese public broadcaster NHK asked me to search for the temple in Takasago where the painting had been acquired, for one of their TV programs. I visited two or three temples and looked into their room layouts and dimensions, but was unable to find one that fit the bill. Had the temple in question disappeared?

After a while I heard from an NHK employee that research on the Internet had uncovered a Zen temple called Chūzanji in Seita-chō, Ise, Mie Prefecture, which had been built during Shōhaku’s lifetime and had an inner room with dimensions perfectly matching those of the painting. I went there at once and measured the dimensions, and while the wall-mounted horizontal beams (nageshi) were a little high, the width was indeed spot-on. Using the latest precision digital technology, a photograph of the painting blown up to its original proportions was mounted on sliding doors and fitted into the room, marvelously replicating its original state. I very much appreciate the cooperation of the temple’s head priest on this project.

In the temple’s hōjō (abbot’s quarters), the recreated sliding-panel paintings depicting the dragon’s front half (head and claws) took up four panels on the west side of the room, and the dragon’s tail and crashing waves took up four panels on the east side, describing an overall curving form. The missing part between the head and the tail must have occupied the north side of the room.

On the far left side are ominous, mirage-like clouds, and moving to the right, first the gigantic claws of the mythical monster appear, then its head, with round eyes that look like old-fashioned bicycle bells. Its long whiskers, resembling whips, must have extended to the doors on the missing north side, which must also have featured the other set of claws. Continuing to the east side, the dragon’s long tail describes a magnificent curve between the otherworldly arabesques of two crashing waves. Shōhaku transformed a traditional ink painting of a dragon into something more like kaiju (a monster, such as Godzilla). His boldness was truly limitless.

But what of the mystery surrounding the temple where Dragon and Clouds was originally executed? The painting Hashimoto Kansetsu reported seeing in the village of Ihozaki must have been a different one, since he said there were two dragons.

As for Chūzanji, in the nearby village of Saigu (also known as Itsukinomiya) there is a private home that contains a surviving Shōhaku sliding-door painting, and he may have painted the dragon in this vicinity, but the height of the painting is a little too short to fit this particular house. This question will need to be placed on hold for while.

Both of the works by Shōhaku just described are in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The museum has a total of twenty-seven paintings by Shōhaku, and is the world’s top collection of his work in terms of both quantity and quality. These were acquired prior to 1911 by Bigelow and Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) and donated to the MFA. However, nobody has any idea what it was about Shōhaku’s works that impressed the two, or how and through whose offices they came to acquire so many of them.

What can be said is that Shōhaku’s paintings seem well suited to the eyes, that is to the aesthetic sensibilities, of American viewers. Graffiti is on the one hand a form of social blight, covering walls in major cities worldwide, and a genre recognized as crucial to the development of contemporary Pop art, as indicated by recent exhibitions like the one at Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris (2009–10). It goes without saying that the United States is the homeland of modern-day graffiti, and after seeing graffiti murals countless times in that country, I have come to note a surprising degree of similarity with the works of Shōhaku in graffiti’s muscular, in-your-face spray-painted lines, powerfully modeled volumes designed to make an impact even at a distance, and profusion of visual playfulness. There is nothing flat about Shōhaku’s folding screen paintings; they have a sense of volume surpassing those of Kanō Eitoku. Is this the kind of thing you would call “Superflat,” I wonder?

Another masterpiece in the Museum of Fine Arts is The Four Sages of Mount Shang (c. 1768), painted when Shōhaku was in his late thirties. This is a terrific example of “graffiti-style” ink painting.

This unusual folding screen depicts the laid-back lives of four elderly hermits hiding out on Mount Shang after fleeing violent conflict at the end of the Qin dynasty (third century B.C.e.). A tree of monstrous proportions, in the style originated by Kanō Eitoku, rises up in a great curve toward the center of the two joined folding screens. On the left side is a wildly gnarled branch, with a hole in it resembling an eye. The branch looks ready to come down and crush the sage who rides below it on donkey, shaded by a large straw hat.

On the right side, at the base of the great tree, the other three old men lounge around, their clothing and the vase of flowers next to them reduced to dashed-off symbolic lines, the entire work seemingly executed all in one breath with audacious strokes. Shōhaku evidently arrived at this distinctive style after being inspired by the wild brushwork of the Zen monk Hakuin (1686–1768), famous for his giant portraits of Bodhidharma.

(Notes)

A short while ago, I heard the news that Yoshitomo Nara was arrested for writing graffiti on the New York subway. He’s setting a standard for you to live up to, Murakami-san!

From Takashi Murakami

The subject for this round was Dragon and Clouds, painted by Soga Shōhaku, in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It was in fact the image of this very Dragon and Clouds that made me give myself over entirely to the world of Professor Tsuji’s Lineage of Eccentrics at the time when I first picked up the book. (Hmm, this essay might get quite serious this time. . . . )

Take the expression of the dragon in this work, its brows furrowed as though it feels pathetic and sad all at once . . . and yet look at its powerful claws, their fierce clutch. And then there’s the utterly unconventional composition, with the dripping ink in the background evocative of abstract paintings. For a young student painter with an agitated heart—that’s me—this was a piece that sent him off on a journey into the world of fantasy with twinkling aspiration.

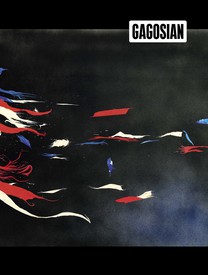

I have since lived, to this date, while holding on to the ambition of mastering this work and painting one of my own. For this round, then, I prepared an enormous eighteen-meter canvas, filling up the largest wall in my Kaikai Kiki studio, confident that I could create something that would transcend the original.

However! The progress has been excruciatingly slow. Actually, I haven’t been able to paint anything. I had the paintbrush made especially for this work. I had an enormous amount of paint mixed. Nevertheless, I have yet to make even a stroke of the brush.

The deadline is in two days. Frankly, the situation is dire, enough to freeze my heart. I have drawn and redrawn the design, but something is not right. Why oh why??

Abruptly on another note, I have been reading a series of books by Kyōko Nakano titled Kowai e (Scary pictures).2 There are some anecdotes in it about dragons in Western paintings, one of which is a drawing of a red dragon by William Blake, The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun (1803–05). This drawing appeared in a novel called Red Dragon by Thomas Harris, of The Silence of the Lambs fame, in which the main character eats the said drawing and becomes a serial psycho killer, supposedly borrowing its power (or delusion).3

I have been reading various such anecdotes, including about this red-dragon image and St. George and the Dragon (1516) by Vittore Carpaccio, emitting sighs of awe and desperation. That is, I’m constantly trying to find a hint for my work for this round. Mr. Takayama (the editor of this series)! I’m not procrastinating! I’m working!!

In the West, dragons are a dreadful presence signifying dark powers, but in China they are fantastical creatures symbolizing good luck and boisterous power and bringing about monetary luck. The two ideas are polar opposites, though I suppose that has nothing to do with my concept here.

So why is it that I can’t paint a dragon? I do hope that by the time this issue comes out, at least some kind of skeletal idea of the work will have left its presence on these pages. (Heavens, have mercy on me!)

Faced with this painting that brought Professor Tsuji and me together, I find myself backed into a corner, my hands and heart paralyzed with fear of exploring the first pangs of love between us. I am hoping for my heart to take a leap of faith, intent on betting everything on that one moment, to take on this challenge.

Now, leap!

The text up to this point was from two days ago, written while I was struggling.

And it’s done! The work is complete!

We did have to ask the printer to make some accommodations and the deputy editor kindly worked on coming up with just the right page layout. (We came very close to missing the issue.)

And hooray, it made it to print! Here it is! Mr. Takayama, you saw the piece getting completed with your own eyes! From sketching the design to completing the eighteen-meter painting, we’ve accomplished the feat in twenty-four hours!

I have combined various elements that have always interested me with the base subject of Soga Shōhaku’s Dragon and Clouds:

• Hokusai’s bright red Zhongkui (Shōki), the Demon Queller (1811)

• The nostrils from a King Crimson album jacket

• Junji Kawashima’s dragon painting on a small folding screen

• Kawanabe Kyōsai’s Theater Curtain of Shintomi-za, with Impromptu Monster Sketches

Contemplating these various things, we, the Kaikai Kiki team, completed the painting in twenty-four hours, with no sleep! Though I have named my studio Kaikai Kiki after Kanō Eitoku, I certainly don’t want to emulate his death by overwork!

Really, this serial project is sapping my life away. . . .

Ah, Nobuo Tsuji the Enanbō is too formidable!

1Hashimoto Kansetsu, Hakusasonjin zuihitsu (Tokyo: Chuo Koronsha, 1957), pp. 180–81.

2Kyōko Nakano, Kowai e, (Tokyo: Kadokawa, 2013).

3Thomas Harris, Red Dragon (New York: Putnam, 1981).

Takashi Murakami artwork © 2010 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd.; text an edited excerpt from: Nobuo Tsuji vs. Takashi Murakami, Battle Royale! Japanese Art History, trans. Christopher Stephens and Yuko Sakata (Tokyo: Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd., 2017), originally published as Netto Nihon Bijutsu-shi (Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 2014)