Emmanuel Burdeau is a film critic. Formerly editor-in-chief of Cahiers du cinéma, he is a writer for Mediapart and the author of many books on film, including recent publications on directors Vincente Minnelli and Werner Herzog. He is currently working on a biography of film critic Serge Daney.

Harmony Korine is a film director, screenwriter, and artist who rose to prominence after penning the film Kids (1995). In the years since, he has created critically acclaimed cult classics, including Gummo (1997), Mister Lonely (2007), and Spring Breakers (2012), as well as the lauded street-art documentary Beautiful Losers (2008). Korine’s creative practice extends to photography, drawing, and figurative and abstract painting.

Harmony Korine Movies are the first thing I fell in love with, and I became known as a movie director, but really I’ve never thought of myself in such a singular way. I write books and poems, make paintings, and take photographs. For me, it was never about mastering a medium, I don’t care about that. It’s more about expression, how can I put what’s inside outside. It’s all interconnected, a “unified aesthetic.” It all comes from the same place, inside me, and it’s all speaking the same language.

Emmanuel Burdeau When did you start to write?

HK By the time I was sixteen, I had a pretty strong sense that I wanted to make movies. I remember seeing a John Cassavetes movie, and Spike Lee’s first movie, She’s Gotta Have It (1986).

Then in high school I took a creative-writing class. I’d never been told I was good at anything by teachers, or anybody, but I wrote a story for this class. I was in the back of the classroom with my head down and the teacher called out my name. I thought I was in trouble but she held up the story and went, “This is the best story.” I was shocked. She made me read it in front of everybody, and at the end of the class, she pulled me aside and asked, “What do you want to do when you graduate?” I said, “I think I want to make movies.” She said, “If I can get you money from the school system, could you turn this story into a short film?” I said, “Of course.” Somehow she got some money. Then my dad gave me a 16mm Bolex camera. So I turned the story into a script and shot it with a couple of friends in New York. It was like a Cassavetes rip-off.

When I went to get the film developed, I walked into this place called DuArt, which was like a lab, and the guy went, “What is this?” I looked so young at the time. I said, “It’s just a film I shot.” He looked around and went, “Do you want to see it projected?” I sat in the screening room alone and watched my footage. I knew it was real. I knew I could do it. I was never scared after that. It demystified everything.

EB How did you get from there to writing the script for what turned out to be Larry Clark’s first film, Kids (1995)?

HK At that time I was in college and living in my grandma’s house in Queens. Between classes, I would hang out all day with the skaters in Washington Square Park. One day Larry Clark came up to me; he was taking photos. We started to talk and he asked me what I was doing. I said I was making movies. It was the days of VHS tapes, and I would keep some in my backpack with all my books, put a sticker on them, and write my grandma’s phone number. And when I would see someone famous or someone I recognized, I’d hand them a tape, say “Watch my films,” and just walk away. So I probably handed him a tape. He called me the next day.

So I went over to his house, I saw his photographs, and it was pretty amazing. I didn’t really know much about contemporary art or the art world back then, but as soon as I met him, he showed me his books and I was blown away. I thought his books were like movies. Tulsa (1971) and Teenage Lust (1983) are still some of the best photography books ever made. We talked about movies and he asked me if I’d ever written anything before. I’d just written a short script during my first semester at NYU. It was about a boy on his thirteenth birthday. His father takes him to a prostitute. He’s a cab driver, and he picks up a girl on the side of the road and basically talks his kid through it as it’s happening. I gave Larry this script and a few days later he asked me to write for him. He had a very loose idea, and wanted to see if I could turn it into a movie.

At that time I was really into certain teen movies like Over the Edge [Jonathan Kaplan, 1979], The Outsiders [Francis Ford Coppola, 1983], Los Olvidados [Luis Buñuel, 1950], and especially Hector Babenco’s Pixote (1981). Movies that were based on reality, and an adolescent world, but that were pushed into the hyperreal, or hyperpoetic. Larry and I both liked the idea of using real people, not actors. I’d never written a script before so I didn’t know how long it would take. I just figured I would write it in a week. And that’s kind of what I did. I sat in my grandmother’s basement with a typewriter, or an early computer, and I just wrote the script very quickly. I didn’t have a real outline, I just knew what it was about, and the kids I wanted to be in the film, because they were my friends. I understood the language, how they spoke, and the rhythm of it, the slang and the cadences. That movie was very stream of consciousness. I just let it go. I didn’t even know what was going to happen until I got to the ending. I didn’t think it would ever really be a movie.

But Larry was really into it, and within a couple of weeks I flew out to Los Angeles and started meeting with producers and financiers. I was nineteen, I’d been in high school just the year before, and I was having conversations about what type of movies I wanted to make, or what type of scripts I was going to write. That was so exciting. When I was growing up, I was told by grown-ups all the things that I couldn’t do, or things I should do, which were never what I wanted to do. This was the first time I thought that maybe I had a chance to make my films.

It’s not about making perfect sense but about making perfect non-sense. It’s about pages missing in all the right places.

Harmony Korine

EB What was your reaction when you first saw Kids?

HK It was exciting, because I’d never seen anything like it. And all the people in the movie were friends of mine. My girlfriend at the time, Chloë [Sevigny], was starring. None of us had ever done anything. So the fact that this movie existed, that we had somehow created it, was a weird, strange, magic moment in time. But it was a hard film.

EB Gummo (1997) is a mysterious film in many ways. It’s not easy to know how to make sense of it.

HK I don’t care about trying to say anything. If the film says something, that’s great, but I’m trying to make you feel something. There’s a physical component that I’m chasing—a sense of unease, or a sense of confusion, transcendence, bewilderment, titillation, humor. I want feelings to come one after the other very fast, so you never really get peace, it’s like an attack. It’s not about being understood. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. It’s not about making perfect sense but about making perfect non-sense. It’s about pages missing in all the right places.

EB You’ve said it’s hard for you to make a film, but you seem like a natural and have very often been described as a prodigy.

HK It’s never easy. At the same time, when I’m making movies, I feel like I’m doing what I’m supposed to do. I also believe, to some extent, that it shouldn’t be easy. There’s always more I need to figure out. I basically film until someone tells me that I can’t anymore. And even then, I try a little more, just to see what happens. When I’m making movies, I never feel like I have enough. I’m always discovering it as I’m making it. The truth is, I don’t even really know what it will be until I’m editing it.

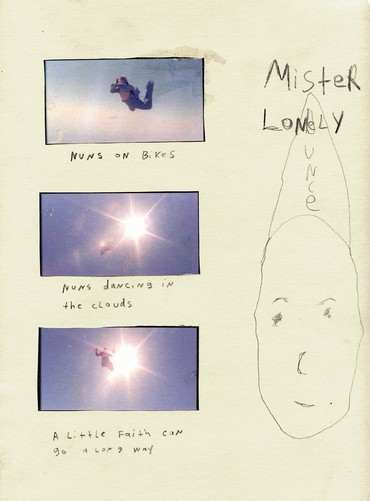

EB Your third feature film, Mister Lonely (2007), deals with the dream of reinventing oneself. How did you come up with the idea of a place where impersonators would gather and create a community of sorts?

HK I don’t know where it came from exactly. In some ways I feel that that’s the strangest movie I’ve made. It almost feels like an anomaly against my other films—it’s the most traditional, but at the same time it’s a very bizarre film. There are moments that are as beautiful as anything I’ve ever done, like the bicycle sequence with the nuns floating in the sky. The singing eggs. But it’s also a strange movie. I was coming out of a fog. That movie still has traces of that fog.

I grew up in a commune, so some of it has to do with that. All the films actually have some autobiographical elements, but I make them because I don’t understand where they’re coming from. I try to think in terms of pure story, characters, and camera. I never have any type of conscious psychology at work. I feel something and then I act on it, mostly.

EB Do you remember how Mister Lonely started?

HK I had a dream about nuns jumping out of airplanes without parachutes. I loved the idea of people having so much faith that they don’t need a parachute. They’re not suicidal, they’re just in such a state of total bliss and self-belief that they think they’ll survive. Then I started thinking about a commune full of impersonators, an isolated area where impersonators could live as the person they’re impersonating. I thought it was a funny premise, and I liked the visual component, the idea of seeing these dead celebrities together in one place. It was intriguing. And also this idea of characters living on the fringes of society, creating their own utopia.

EB Why did you decide to move from Nashville to Miami?

HK I’ve always been intrigued by the psycho-geography of Florida. It’s part of America but it’s separate. There’s something about it that really is difficult to articulate. It doesn’t really produce anything, it’s just an extension of people’s dreams and fantasies. Extreme wealth and extreme poverty are smacking up against each other, both sides influencing each other, everything blurring under a pink sky.

EB How different is Miami from Nashville?

HK Nashville is older, and it’s the South. Miami is more like Latin America, it’s a totally different vibration. There’s a kind of anti-intellectualism that I like. I’ve spent so many years being provoked, or provoking—I wanted to go somewhere where I could just feel. I ride my bike around the boardwalk, drink Cuban coffee, smoke cigars. The palm trees, the sky, the boats, the architecture, all of that is appealing to me.

EB How would you describe that vibration?

HK It’s like a transcendent criminal dream.

EB Like in Spring Breakers (2013)?

HK Sure. It’s a mind-set. Everyone is on a hustle.

EB What was the image that triggered Spring Breakers?

HK I had a vision of girls in ski masks and bikinis robbing tourists on the beach. I wrote a script very quickly, just a skeleton, with thirty lines of dialogue. I wanted to make a film that was like electronic music using samples, I wanted a repetition to it. The same way DJs can loop music, I can loop sequences. The narrative would explode and become more liquid, almost like a video game.

So I began collecting spring-break imagery: pictures of pool parties, coed pornography, kids in cheap motels puking in the hallways, violence. There was something interesting in those images, it was a world in itself. In some ways it’s very common, and in other ways it has a pathos. Spring break is a rite of passage. I was also interested in the way it looks: the colors, bikinis, shadows from palm trees, trailer homes, resorts, beaches. How things look under neon at night, the harshness and strangeness of the lightning, the presence of water. It started to speak to me like a weird pop poem. That’s when I just made up the story.

EB Were you happy with the reaction you got for Spring Breakers?

HK Yes. In some ways I think it’s my most successful film. With my other films, they often made a substantial impact on youth culture, but it takes a long time. It was nice with Spring Breakers that the reaction was more immediate.

EB Did you also get bad reviews?

HK Of course. Every movie I’ve made has been divisive. With Gummo I thought that people who didn’t like it would at least see the heart of the film, and that there was something substantial. But so many people were just vicious, coming after me in a personal way. Some people think about the films in terms of pure provocation, which they’re not. You can’t let that bother you though.

EB Didn’t it stress you in any way?

HK The films are meant to provoke. I’m not a politician, I’m not trying to get the most votes. I have something very specific that I want to see and I have a short amount of time to do it. Life is so fast, I just want to enjoy it, to make things that are beautiful, to make mistakes and entertain. Once it’s out there, the reactions are what they are.

EB Do you also get strange or interesting reactions to your paintings?

HK It’s different. Art takes place in a slightly more rarefied world. It’s not as popular. You usually do a show in one space at one time. With movies, you blast them to the world all at once.

Life is so fast, I just want to enjoy it, to make things that are beautiful, to make mistakes and entertain.

Harmony Korine

EB You seem to have found a good balance between artwork and movies.

HK I’m slow with movies. I do shorts and videos, but I only make a long film every five or six years. So it’s nice to be creating other things. Actually, when I’m not in the studio for a while, I miss it a lot. I start to get agitated. When I’m working on something creative, it always comes from a similar place. There’s a satisfaction in acting on a creative impulse. The worst is when you’re not doing anything.

Painting is like writing: it’s direct. You’re not in charge of a hundred people. If it comes to you, you just put it out there. I can write “A helicopter flying over Miami smashes into a yacht, blows up, and kills thirty people,” I don’t have to figure out how to execute it. Painting is even nicer because you don’t have to justify yourself. It’s something that just exists because you want it to exist.

EB When did you start painting?

HK I’ve always done paintings and drawings, but in a private way. I had exhibitions early on, when I was younger, but I never really pursued it fully. The films were public, the artwork was more personal. I’ve only started showing it more in the last couple of years.

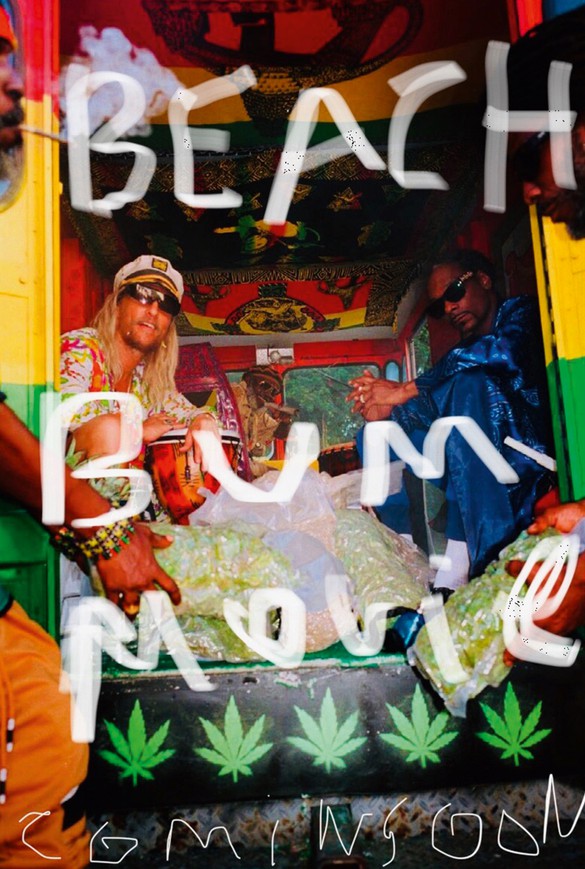

EB Your next project is called The Beach Bum. Is it going to be similar to Spring Breakers?

HK It will be a continuation of that style but for a totally different world, setting, and story line. It will be like a stoner movie. When I was a kid, in the ’70s, there was a Mexican comedy duo called Cheech and Chong. They made movies, like Up in Smoke (1978), that were just about these two guys living in LA smoking huge joints. They were great.

EB Rumor has it that you might adapt for the screen a novel called Tampa.

HK Yes, that’s for HBO. The author is Alissa Nutting. She’s in her mid-thirties, married with a kid, and she lives outside of Cleveland. I’ve already written the script.

The book came out three years ago. It’s about a teacher in Tampa who has sex with her middle-school students, like twelve- or thirteen-year-old boys. It’s written in the first person so it’s her mind, her account of how she does it, how she picks them, how she manipulates them. It’s interesting because I’d never seen that psychosexual dynamic before. If it was a guy doing that to girls, you’d hate him, but somehow, when you reverse it, when you read the book, especially if you’re a guy, it’s titillating. As a teenager I used to sit in class and dream about having sex with my teachers, even the most disgusting ones. It’s a time in your life when it’s uncontrollable. So, when I was reading the book, I was experiencing it through the boy, and I didn’t know if it was so bad. But then there’s a moment and it becomes very bad. That’s amazing—very quickly it goes from titillating to sociopathic.

When you’re reading the book, you know it’s fiction, but she has these elaborate scenes. It’s not like Lolita, with super-beautiful prose. The syntax is more of this time. She had to let her mind go to this dark place.

EB Do you have any idea about what the next step could be for you?

HK I feel like I might be starting a new phase of work. I just want to develop it. The thing is, I feel like a kid in a lot of ways. At the same time, I’ve been doing it for a long time. It’s strange.

Interview published in full in Harmony Korine (Rizzoli Electa, 2018; published in association with Centre Pompidou and Gagosian)

Artwork © Harmony Korine

Text © Harmony Korine and Emmanuel Burdeau