Now available

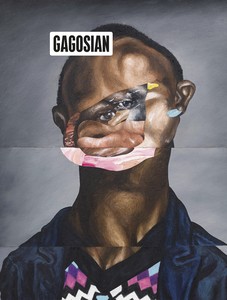

Gagosian Quarterly Fall 2019

The Fall 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Sinking (2019) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn on its cover.

Fall 2019 Issue

Alexander Wolf explores the economic, social, and methodological concerns of Piero Golia’s art practice, revealing the real-world implications of the artist’s experiments with form and process.

Piero Golia. Photo: Nicole Miller

Piero Golia. Photo: Nicole Miller

Among the spectacles lacing LA’s Sunset Strip, some have noticed a mysterious glowing orb just above the roof of the Standard Hotel. “Maybe a commuter who drives past it every day will decide that it lights up on sunny days, or on rainy days—it’s a form open to urban legend,” mused Piero Golia when he placed this spherical light on the hotel’s roof ten years ago.1 It presents as a surprising and elegant diversion, in the spirit of Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913) or Golia’s late friend Chris Burden’s Urban Light (2008), the chorus of 202 antique streetlights gathered outside the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. But when one learns that Golia’s Luminous Sphere lights up only when he is in Los Angeles, its prime perch and cool openness to interpretation give way to clear motives: a European newcomer’s announcement of his arrival, and his attempt to reach, through sculpture, LA’s urban sprawl.

Golia’s unpredictable corpus—made up of artworks and actions that can seem impossible, and are therefore few and far between—is built on a deliberate process of trial and error, as he cultivates the runoff of one work or life event into another, and then another. His project is utterly generous and inclusive: he is eager to lift fellow artists and to foster the LA art community, even at his own great expense. Golia’s practice also seems influenced by a conviction that in a visual-art field where many norms remain to be challenged, it would be impossible to restrict oneself to the parameters of painting, sculpture, and the studio, traditions that he questions, often with a shade of irreverence. Golia does not keep a studio, and quite like the rogue gestures of Duchamp and Burden, his work is predicated on subversive play.

Golia’s tactile art—paintings and sculptures seen in museums and galleries over the past twenty years—is but one aspect of a body of work that has also encompassed targeted actions, epic performances, a self-inflicted disappearance, a nightclub, and the founding of an art school: work that exists and functions in the real world, not on a wall or pedestal, and often not in any place where one would go looking for art. When his work does manifest as a beautifully crafted object, that object will often tell of an event that has taken place out in the world. Taken together, these events constitute a constructive critique of art systems, paralleled by Golia’s orchestration of an LA moment and a continuous, rough-hewn international odyssey.

Car Trouble

Upon his arrival in Los Angeles in 2002, Golia made and sent personal calling cards bearing only his name to several leading artists. “To me it was the idea that you come to a new place and politely introduce yourself,” he recalls. He soon felt welcome. “LA spoiled me very much because the artists there were incredibly kind.”2 It wasn’t long before Golia made his own local but far-reaching contribution: he and the artists Eric Wesley and Richard Jackson gradually developed a free, bare-bones, yet ambitious graduate school—no tuition, no degree, but a vigorous curriculum—centered on talks and seminars led by visiting artists and curators. The Mountain School of Arts was born in 2005 in an upstairs nook at the Mountain, a Chinatown bar. Over the past fourteen years, the program has evolved into a forum where hundreds of students have received instruction from guest faculty including the artists Tacita Dean, Thomas Demand, Simone Forti, Dan Graham, Mark Grotjahn, Pierre Huyghe, Catherine Opie, Jeff Wall, and many others.

Piero Golia, Untitled (Bus), 2008, crushed public transportation bus, 10 × 20 × 10 feet (3 × 6 × 3 m). Courtesy Fundación/Collection Jumex. Photo: Joshua White, courtesy the artist

The works that Golia produced during his first years in LA can be described as a former engineer’s solutions to real problems, realized as sculpture. (As a twenty-three-year-old studying chemical engineering in Naples, Golia had visited New York for the first time, and the rest is history.) Following a car accident whose costs were not covered by his insurance, Golia melted down what was left of his 1984 Saab and planned to recast it as a sculpture to be sold. Given the project’s commercial purpose, he embarked on an online deep dive for the most popular sculptural subjects, which prompted him to cast the liquid metal into a glossy black unicorn the size of a pony. Invited to exhibit it in the Statements sector at Art Basel Miami Beach, he imagined that it might attract a pop star who appreciated his take on the fantastical creature, but wasn’t disappointed when it was purchased by a collector who appreciated the story as much as the subject. (In 2011, his first solo exhibition at Gagosian demonstrated a similar resourcefulness with the Concrete Cakes, which were made from a gift of unwanted cake molds. The Constellation Paintings were made from the debris of yet another car accident, this one intentional, when a taxi driver accelerated his car into Golia’s home following an argument over a fare.)

The first presentation of Golia’s work in his adopted hometown of Los Angeles took place in 2008, when he was invited to take over an entire booth at the Art LA art fair. He acted on his interest “in digging into the idea of the weird space of the art fair itself—in the end, it’s not an exhibition space. I decided to focus on completely filling the booth. It was, in a way, a kind of territorial marking, to define the space with the physicality of a sculpture.” Golia’s initial solution was the purchase of a thirty-five-foot passenger bus. When the booth turned out to be smaller than expected, he enlisted three bulldozers to compact the bus to the dimensions of the ten-by-twenty-foot space.3 The talk of the fair, Golia’s crushed Bus elicited surprise, confusion, and delight.

Taken together, these events constitute a constructive critique of art systems, paralleled by Golia’s orchestration of an LA moment and a continuous, rough-hewn international odyssey.

Between the growing reputation of the Mountain School and the astonishment surrounding Bus, Golia found that he was reaching an audience for the first time. “That’s the moment when you double down and say: now I have a public,” he reflects. Continuing to think in terms of the potential of sculpture to reach and connect people, he soon dreamed up Luminous Sphere. “I think the light on the Standard is the moment when I started to dialogue not only to the people I surround myself with,” says Golia, “but also with others who live in the same place I do.” The work was installed on the hotel’s roof in 2010 and remains there, announcing Golia’s presence or absence to mostly unaware drivers-by.

One afternoon in the fall of 2013, I bumped into Golia at Gagosian’s 24th Street gallery in New York. He gave me a solid silver token and mentioned something about a “chalet” in Los Angeles. I had no LA plans and promptly misplaced the token. In the following months, an artist here, a dealer there, would recall an evening at “the chalet.” I pieced together an image of this temporary and now legendary destination: an incognito jewel box of a nightclub featuring, on any given night, a marching band, dinner by a celebrated chef, a friendly family of alpacas. The sleek space was designed by the architect Edwin Chan and the walls were lined with works by Grotjahn, Wall, and Christopher Williams, as well as an aquarium by Huyghe. Golia took on the roles of manager, talent agent, electrician, and more. Having devoted years and all of his own savings to the project, he feels it was well worth it. As Golia described his incentive, “In LA you never get to see your friends. I thought, ‘The place should be so fantastic and special that—finally—people will agree to leave their homes . . . the Chalet is a tool for community-building.”4 Chalet Hollywood was open to all on select evenings for sixteen months. Guests ranged from artists, curators, celebrities, poets, dancers, fashion designers, and bankers to “punks” who came for the free booze.

Installation view, Piero Golia: The Chalet Hollywood, May 2013–November 2014. Photo: Jeremy Bitterman, courtesy the artist

Comedy of Craft

In 2014, Golia was invited to participate in Made in LA, the biennial exhibition at LA’s Hammer Museum. To his mind his contribution needed to be monumental, and he wanted museum visitors to witness its creation. Golia proposed that he and a team of volunteers would carve a to-scale replica of Mount Rushmore from foam. When the impossibility of this plan became clear, he decided to zoom in and approximate the form and scale of one of Rushmore’s more prominent features: George Washington’s nose. Over the course of the nearly three-month-long exhibition, Golia and his team carved out an eighteen-by-twenty-one-foot slope from a massive block of Styrofoam.

Exemplifying how his works have a tendency to morph and provide a basis for other works, at some point Golia decided that the nose should ultimately be cast in bronze. So, later that year, at the New Orleans art festival Prospect.3, he enlisted a group of art students to make a rubber mold. Viewers witnessed the foam carving that had been created at the Hammer (one local reviewer likened it to a “two-story igloo”)5 and a group of students gradually covering it in liquid rubber. Golia described this as act 2 of a Comedy of Craft (equating his sculptural process with the improvisational, fluid spirit of the Italian commedia dell’arte performances of old), with Washington’s nose as protagonist: act 1 being the initial carving, and the final bronze casting planned as act 3. “Art,” Golia says, “is like theater.”

Piero Golia, The Comedy of Craft, Act I, 2014. Installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Joshua White, courtesy the artist

Piero Golia, The Comedy of Craft, Act II, 2014. Installation view. Photo: courtesy the artist

Installation view, Piero Golia: Intermission Paintings, Gagosian, Rome, 2015. Photo: Matteo D’Elleto

At this point, though, Golia’s trilogy met a sudden end. Following Prospect.3, the New Orleans storage facility where the mold was being kept was sold to another storage company, which discarded the mold as trash. Although the first president’s nose wasn’t memorialized in bronze, all was not lost. Following the carving phase, Golia had kept the excess shards of foam, which he coated in a hard, paintable polymer and sprayed with iridescent nanopigments normally used to print currency (an allusion to their being among the only saleable output from his epic Comedy?). He called them the Intermission Paintings, given their origin as the cutaways from act 1. Exhibited at Gagosian in Rome in 2015, these irregular sculptural works evoke magical rock formations but, being foam, are in fact almost weightless. Golia later used additional foam fragments as the basis for the Lamps (2018), asymmetrical tabletop forms fitted with lightbulbs, and as such equal parts sculpture and useful furniture. In a domestic mise-en-scène, Golia showed these works along with geometric marble Fruit Bowls and paintings he had made from upholstery at Gagosian in Beverly Hills in 2018.

Piero Golia, Untitled (My Gold is Yours), 2013. Presented at the Venice Biennale, 2013. Photo: Laura Einaudi, courtesy the artist

The Value of Art

Invited to represent Italy at the 2013 Venice Biennale, Golia put forth what at first appears to be a Minimalist 2.5-meter-square concrete cube. On closer look the surface is embedded throughout with threads of bright gold, as though the concrete were protecting a resplendent mass at its core. In fact Golia had mixed two kilograms of gold sand into the much larger amount—thirty-six tons—of concrete. In Venice he invited viewers to mine the gold from the block by whatever means available (keys, pocketknives), leaving the value of the material, not to mention the ultimate appearance of the cube, in the hands of the viewer.

Golia has continued to investigate the sometimes mysterious yet very real monetary value of some art, and, with that value, art’s ability to resolve pesky financial issues. Whereas many artists make deliberate efforts to isolate questions of commerce from their creative processes, Golia often disrupts that protocol—in the melted-car-turned-unicorn sculpture, for example, candidly made to cover his insurance costs. In 2017, in response to the art market’s demand for domestically scaled abstract paintings, Golia assembled The Painter, a thirteen-ton piece of machinery, adapted from movie-studio technology, armed with a paintbrush. Visitors who entered the gallery at the Kunsthaus Baselland where it debuted saw a row of paintings in progress and the reprogrammed machine strutting down a fourteen-meter track to greet them. Then it would glide to one of the canvases to apply new gestural brushstrokes that charted the viewers’ movements through the gallery. The paintings were declared finished at the close of the exhibition.

Installation view, Piero Golia, Kunsthaus Baselland, Muttenz, 2017. Photo: Gina Folly, courtesy the artist and Kunsthaus Baselland

The Chalet soon reincarnated as a special exhibition at Dallas’s Nasher Sculpture Center, where it produced such events as a Christmas party colored by Paul McCarthy’s grotesque Santa Claus imagery. When the time came for Chalet Dallas to close, it got a grand send-off culminating in fireworks and the drop of a massive curtain bearing the orange-red vortex and cursive “That’s All Folks!” finis from the old Looney Tunes cartoons, all to the live music of a youth mariachi band. After the fact, Golia learned that this band of adolescent musicians had been invited to compete in a prestigious mariachi competition in LA, but did not have the funds for the trip. So he cut the “That’s All Folks!” curtain into twelve large vertical sections and stretched them to create the Mariachi Paintings: fragments of a familiar childhood image that are also vestiges of the Chalet moment, which touched Angelenos and Texans alike. Golia sold the first painting himself for the amount needed to fund the band’s trip to LA, where it placed first in the musical contest.

Piero Golia, Mariachi Painting #1, 2016, dye sublimation on fabric, 84 × 48 inches (213.4 × 121.9 cm). Photo: Ben Lee Ritchie Handler

Piero Golia, Chalet Dallas, 2015–16. Closing performance. Photo: Bret Redman, courtesy the artist and Nasher Sculpture Center

By 2018, the ambitions of the Mountain School had outpaced its operating budget. Golia resolved that art, not credit, would come to the rescue. He called several artist friends, many of whom had played a role in the school’s life—Huyghe, Williams, Harold Ancart, Frances Stark, Henry Taylor, and others—and asked if they would donate works for the cause. He concealed the works inside piñatas shaped as the numbers 1 through 10, hung them from a balcony in a friend’s backyard, and threw a party at which guests paid $200 per swing of the bat—and posed the conundrum of potentially damaging the art inside the piñatas in order to secure it. Many went home with new artworks, and the Mountain School lived on.

Trial and Error

Golia recently attended the opening of Jeff Wall’s first exhibition at Gagosian, in New York. Among the nine large-format photographs on view, Wall had made a nearly ten-foot-wide gelatin-silver print showing a hulking weightlifter, the barbell he held at his waist bending under the pressure of the heavy discs at its ends: an analogy for the often solitary, at times seemingly futile process of making art. Golia, who has moved his share of bureaucratic mountains to realize his work, reasoned that an artist’s process can be even more isolated: “When you lift weights, you have a guy who tells you how to do it. When you make art, you have to figure your shit out on your own.”

Back in 2003, as a young artist, Golia was invited to present a work in the vast, centuries-old gardens of the Villa Medici in Rome. His first proposal was to remove a swath of towering Renaissance-era cypresses, oaks, and pines just long enough for people to register their disappearance, then replant them precisely where they had been (even then Golia derived satisfaction from at least attempting the impossible). What was ultimately staged was a performance that began with the distant rumbles of a drum line, which grew louder as the band approached the audience. Golia had miscalculated by positioning the musicians so far away that the onlookers scattered before they arrived, and he stopped the parade. Fifteen years later, in 2018, Golia and the Villa agreed to revisit the performance. This time the band marched from the point where it had stopped all those years before, reached its audience, and performed the long-pending grand finale—though perhaps “finale” is not the right word. When the music stopped, a forty-foot fireball lit up the night, and three words were formed in the flames: “To be continued.”

1 Piero Golia, quoted in Jori Finkel, “In Los Angeles, Art That’s Worth the Detour,” New York Times, May 1, 2009. Available online at www.nytimes.com/2009/05/03/arts/design/03fink.html (accessed June 2019).

2 Unless otherwise noted, quotations of Golia in this essay come from a conversation with the author, May 1, 2019.

3 Golia describes Bus and details on the project in an interview with Andrew Berardini, “Artists at Work: Piero Golia,” Afterall, December 15, 2008. Available online at www.afterall.org/online/artists.at.work.piero.golia#.XRKQ1utKhaR (accessed July 25, 2019).

4 Golia, in “Conversation with Piero Golia and Edwin Chan,” an interview on the occasion of Golia’s special exhibition Chalet Dallas at the Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, in 2015–16, a condensed version of which is published online at www.nashersculpturecenter.org/learn/research/articles-publications/article?id=56 (accessed June 2019).

5 See Doug MacCash, “George Washington’s giant schnoz is a Prospect.3 standout,” Nola.com, October 31, 2014. Available online at www.nola.com/arts/2014/10/george_washingtons_giant_schno.html (accessed July 25, 2019).

Artwork © Piero Golia

Alexander Wolf is a director at Gagosian in New York. Since 2013, his projects at the gallery have included exhibitions, communications, and online initiatives. He has written for the Quarterly on Piero Golia, Nam June Paik, Robert Therrien, and other gallery artists.

The Fall 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Sinking (2019) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn on its cover.

Andrew Berardini reflects on Piero Golia’s Intermission Paintings, relics from the first phase of the artist’s three-part sculptural performance The Comedy of Craft.

David Cronenberg’s film The Shrouds made its debut at the 77th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in France. Film writer Miriam Bale reports on the motifs and questions that make up this latest addition to the auteur’s singular body of work.

Alison McDonald celebrates the life of curator Richard Marshall.

Alice Godwin and Alison McDonald explore the history of Roy Lichtenstein’s mural of 1989, contextualizing the work among the artist’s other mural projects and reaching back to its inspiration: the Bauhaus Stairway painting of 1932 by the German artist Oskar Schlemmer.

The mind behind some of the most legendary pop stars of the 1980s and ’90s, including Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and the Buggles, produced one of the music industry’s most unexpected and enjoyable recent memoirs: Trevor Horn: Adventures in Modern Recording. From ABC to ZTT. Young Kim reports on the elements that make the book, and Horn’s life, such a treasure to engage with.

Louise Gray on the life and work of Éliane Radigue, pioneering electronic musician, composer, and initiator of the monumental OCCAM series.

Tracing the history of white noise, from the 1970s to the present day, from the synthesized origins of Chicago house to the AI-powered software of the future.

Ariana Reines caught a plane to Barcelona earlier this year to see A Sea of Music 1492–1880, a concert conducted by the Spanish viola da gambist Jordi Savall. Here, she meditates on the power of this musical pilgrimage and the humanity of Savall’s work in the dissemination of early music.

Dan Fox travels into the crypts of his mind, tracking his experiences with goth music in an attempt to understand the genre’s enduring cultural influence and resonance.

Charlie Fox takes a whirlwind trip through the Jim Shaw universe, traveling along the letters of the alphabet.

On the heels of finishing a new novel, Scaffolding, that revolves around a Lacanian analyst, Lauren Elkin traveled to Metz, France, to take in Lacan, the exhibition. When art meets psychoanalysis at the Centre Pompidou satellite in that city. Here she reckons with the scale and intellectual rigor of the exhibition, teasing out the connections between the art on view and the philosophy of Jacques Lacan.