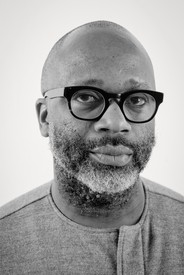

Chris Dingwall is a historian of race and capitalism in American culture. His first book, Selling Slavery: Race and the Industry of American Culture, is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. He is beginning a new book project on African American design in Chicago. He lives in Detroit and teaches at Oakland University.

How do you renew the color of bricks? According to the Chicago Defender, in its Big Weekend edition of September 3, 1910, it took ammonia, linseed oil, or a paste that you could buy at a local brickyard:

When red bricks in the fireplace get discolored with soot or have white spots on them rub them with a brick polish, the paste for which can be obtained at a brickyard or paintshop. If this paste cannot be found rub the bricks well with linseed oil, giving them all they will absorb. . . . Where brick pavements are discolored with moss or green mold scrub with a strong solution of household ammonia and water or with washing soda and hot water.1

To the readers of the Defender, then the leading newspaper of the growing African American community on Chicago’s South Side, this was practical advice: clean the chimney or the pavement with stuff from the pantry or a corner store. Because racial segregation made money and public services scarce for African Americans, many South Siders adopted practices of renewal and care to beautify their homes and neighborhood. How to renew the color of bricks became a metaphysical proposition. By applying some labor to sooty or mossy bricks, by “giving them all they will absorb,” you could renew not only their color but the social worlds they contained.

A Chicagoan who has maintained a studio in the South Side for more than ten years, Theaster Gates has made the ethic of brick renewal the basis for a sprawling artistic practice. By purchasing, restoring, and repurposing dilapidated properties in his Grand Crossing neighborhood, he has demonstrated a keen sense of the values that dwell in Black spaces and objects—and of the labor needed to reactivate those values. His success in creating new zones of investment and beauty in Chicago is undeniable. In the past decade, Gates has helped to revitalize Grand Crossing, gained international renown in the art world, and brought critical attention to the politics of race, money, and land in the formation of Black cultural institutions. Yet his reputation as a “real-estate artist” has sometimes overshadowed critical aspects of his practice. In recent site-specific installations and exhibitions, Gates has shifted attention from his cultural enterprises to the mundane materials that he uses to build them: wooden planks, roofing tar, bricks. Bricks—clay transformed by hand and fire into sturdy blocks—are especially prominent. With his brickwork, Gates reminds viewers about his own early work as a potter. But he also means to change how we see the work of art itself, from its origins in the most elemental materials to its radical capacity for renewal.

For Gates, bricks are works of art, and works of art are something like bricks. In How to Build a House Museum, an exhibition held at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, in 2016, Gates dedicated a room to bricks made by George Black, whose North Carolina brickyard, founded in 1940, supplied the region and is now a site on the National Register of Historic Places. In the middle of the room, titled The George Black House, Gates assembled dozens of Black’s bricks into two neat stacks, one elevated on a metal support and the other piled on a shipping pallet. The placements gestured to the typical ways that Black’s bricks had been and could be displayed: as an artifact of African American craft tradition and as a commodity for sale. As both an entrepreneur and a craftsman, Black serves as a progenitor of Gates himself, who has also claimed a precedent in the work of David Drake (Dave the Potter), an enslaved ceramicist who inscribed poetry into the vessels that he made for his master to sell. In both cases, Gates places himself in a longer lineage of Black artists and cultural producers who have worked under exploitative conditions of white supremacy and commodity capitalism. Yet the tableau also showed Black’s bricks as something besides building material or artifact. On a wall-mounted plaque, Gates offered an elegy for Black that elevated brick to the status of sculpture. Black was “alchemist of the earth and maker of brick,” his art nothing less than the molding of clay into permanent form: “When man returns to the earth as dust the brick remains as monument to man’s capacity to harness the lowest particles that it might act as a marker of his achievement.”

Bricks have since reappeared as material and metaphor in several of Gates’s exhibitions. Following his contact with Black’s family, Gates has used bricks from North Carolina and has made his own in his Chicago studio, where he grinds down and reforges old bricks sourced from around the city. The recycled bricks—now colored glossy black—are the primary building material for Black Vessel for a Saint (2017), an outdoor shrine commissioned by the Walker Art Center for the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. A monumental black cylinder with a hollow interior, open to the sky, Black Vessel is the new home for a “homeless” statue of St. Laurence that Gates rescued from a soon-to-be-demolished Chicago church. Like The George Black House, Black Vessel materializes the history of African American material culture and Gates’s projects in Chicago. In this light, the shrine serves as a proof of concept for an envisioned brick-making enterprise with “the potential to employ 200 or 500 people to help me make those bricks,” Gates explained. But if part of “the idea of the brick” as he noted, is the “pragmatism of Black entrepreneurship,” that pragmatism depends on a more radical speculation about the nature of things to transform and sanctify social space. Whereas in Toronto Gates showed bricks as sculptures, in Minneapolis his brickwork presented a sculpture as a vessel: a thing that gathers, holds, and houses social experience. Black Vessel is at once a sanctuary and a home, a modest monument and a gigantic pot. “I think my investment in the creation of bigger spaces and their philosophies,” he added, “is deeply rooted in my ability to create a good pot or tea bowl.”2

By using mundane materials to awaken and shape states of social being, Gates’s brickwork joins several recent practices of material repair and renewal, from the Italian Arte Povera movement to the monumental brick installations of Doris Salcedo, whose Abyss (2005), installed at Castello di Rivoli in Turin, he cites as an inspiration. For his part, Gates has been developing a social theory of sculpture from the beginning of his artistic career. More than reflections of histories or cultures elsewhere, his sculptural work means to gather people and things into new formations. In Plate Convergence, an exhibition staged at the Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, in 2007, Gates made his artistic debut by hosting a dinner to honor the legacy of Shoji Yamaguchi, a fictional Japanese potter whose ceramic plates (made by Gates himself) served as vessels for African American soul food. Plates, like bricks, exhibit the capacity of art to create occasions for critical reflection and cultural exchange. Like Heidegger’s jug, Gates’s ceramics, sculptures, paintings, and space-based practice mean to give tangible form to social worlds that have receded from view or which do not yet exist, as a plate is made to serve a future meal that has yet to be cooked, and a brick is made to house a family that has yet to be formed. “The jug is not a vessel because it was made,” as Heidegger theorized; “rather, the jug had to be made because it is this holding vessel.”3

Yet for Gates that capacity of the vessel to hold is intimately related to the work of making the jug. As he has shown in numerous video interviews and live performances, Gates discovers the cultural histories and social potential that dwell in his materials through the process of labor, a discipline of craft that he credits to his father, a roofer. In the artist’s book that accompanied 12 Ballads for Huguenot House (2012), a project for Documenta 13 in which Gates renovated an abandoned hotel in Kassel, Germany, using materials salvaged from a building in Grand Crossing, he distilled his theory into a visual equation: “LOVE + LABOR = VALUE.” That materials absorb the love of the laborer was an idea implicit in Gates’s earlier ceramic work and licensed his burgeoning social practice, a “Machine for Cultural Production” that would renew the political economy of a whole Chicago neighborhood.4 A system that would cycle between states of capitalism and socialism, his machine might be seen as both his largest sculptural work and his most capacious theory about what sculpture is: a means to transform and recircuit systems of power. “It takes money to solve social problems,” he explained to Artforum in 2016; “it takes hard conversations and political power—artists should also sculpt those things.”5

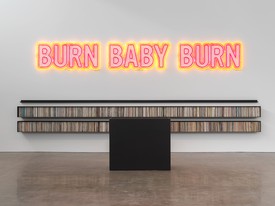

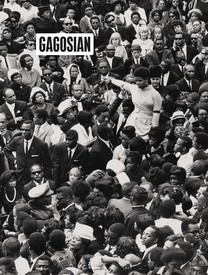

Why do we renew the color of bricks? At its highest level, Gates directs his art of renewal to the legacies of African American cultural enterprise, most recently in Black Image Corporation (2018–), a traveling exhibition that features nearly three thousand images from the Johnson Publishing Company archive. The exhibition notably features Gates’s Facsimile Cabinet of Women Origin Stories (2018), a repository and interactive archive that recontextualizes and reanimates these images and their histories. Yet as his artistic practice operates on ever greater scales of social power, so has his sculptural practice become ever more hands-on. At Gagosian this September, Gates’s bricks will form another Black vessel, yet one that will house not a saint but a series of works that, like his brickwork, renew the value of mundane materials: paintings made with tar, poems on the spines of bound volumes from Ebony and Jet magazines, cages that hold offcuts of fire hoses, and ceramic vessels. At once a vessel and a void, the exhibition will reawaken the material culture of Black Chicago while acknowledging the intimate origins of the work of art: the everyday labor of bringing a social world into being.

1“How to Renew Color of Bricks [sic],” Chicago Defender, September 3, 1910, p. 8.

2Theaster Gates, interview by Victoria Sung, August 27, 2019, https://walkerart.org/magazine/theaster-gates-discusses-black-vessel-for-a-saint (accessed May 9, 2020).

3Martin Heidegger, “The Thing,” trans. Albert Hofstader, in Poetry, Language, Thought (New York: HarperPerennial, 1971), p. 166; see Bill Brown, “Redemptive Reification (Theaster Gates, Gathering),” in Theaster Gates: My Labor Is My Protest (London: White Cube, 2012).

4Theaster Gates, 12 Ballads for Huguenot House (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012), pp. 26, 29.

5Theaster Gates, as told to Zachary Cahill, Artforum, May 3, 2016, https://www.artforum.com/interviews/theaster-gates-speaks-about-his-drawings-and-conceiving-exhibitions-59861 (accessed May 9, 2020).

Artwork © Theaster Gates