Ron Trent is best known for founding the legendary Prescription Records, Future Vision, Electric Blue Recordings, and his latest imprint, Music and Power. In order to preserve and perpetuate its essence to the new generation, Trent has set up the SODA Foundation to ignite the preservation of the ethos of underground music culture. Photo: Marie Staggat

On Frankie Knuckles

The spirit of Frankie Knuckles’s music, and what he was doing in Chicago, met me before I met him. That was at the beginning of the 1980s, when I was a young guy and first wanting to express myself creatively with records. Before, because of my upbringing, I had really been interested in playing instruments. Being a child of the 1970s, you know, you wanted to have a band.

So through neighborhood folkloric energy [laughs], let’s put it like that, Frankie Knuckles’s name started getting into my ears as the person behind some of this new style, this new underground thing that was happening. It was word of mouth and mysterious; it wasn’t commercial on any level. That had to be somewhere around 1982.

Later, I got a chance to actually meet him in person, around 1989 or 1990. I had put out this record “Altered States” with Armando Gallop’s independent label, my very first release. Frankie was playing my record and he had started to work with Def Mix and Dave Morales and Judy Weinstein. He had left Chicago and was blowing up worldwide, traveling and starting to do his thing abroad in a bigger way. He would have these homecoming reunion parties, if you will, and everybody who was part of the whole Warehouse, Powerplant, Gallery 21 scene would be like, “Oh, Frankie’s coming back.”

Whereas Chicago had been used to the classic Frankie, who played a lot of older music, new audiences knew him for playing more what they called “New York underground,” a combination of new stuff coming out of New York City, imported records coming out of Italy, and newer productions coming out of London. It was a new sound. And my record had been put in his hands, so when he came back to play this party, at this place called AKAs, he played my record multiple times that night.

The sound system, as they say in reggae culture, is like the information center. Cats would chant on the mic and talk about different things—the sound was introducing new ideas. The DJ in our culture was doing that too, educating people about new music and turning them on to new things. So Frankie rocked my jam three times, you know what I’m saying? I was like, Wow, shit. It was kind of like a synergy was created there. Then over the years, man, we would see each other or get on each other’s phone lines and just talk about different things. He was much older than I was; I’m like a little brother to Frankie Knuckles because, you know, he was my elder and mentor. But we were coming from the same place, the same vision.

I look at our work from a very ethereal standpoint. You’re doing a sacred thing, really—you’re playing music for people, you’re lifting their spirits. It’s another form of church, if you’re into that kind of thing, but even deeper than that: it goes back to the tribal connection, the sonics bringing together a zeitgeist, creating a spirit, and then healing everybody.

People deal with things, nowadays especially, with a very surface-level philosophy, you know? DJ’ing suffers from that now, because people stand up there posturing or whatever the case may be. But the truest essence of this culture is based on storytelling, which goes back to an older methodology. Going back in African culture, and many ancient philosophies around the world, people used a storytelling method to educate the community, right? And records are like books; they’re little pieces of somebody’s story encapsulated in something tangible.

Back in the 1970s, 1980s, guys would take records and edit them. It was their selection of records that told the story. Frankie’s story was different. You could hear the beauty that he was into. He was into a lot of strings, he was into pianos. Somebody like Ron Hardy, who was another innovator in our scene, was into a rough, raw, hard kind of element. Radical. Frankie, on the other hand, was into refinement, and you could hear it in the production and his sets.

All that ethereal stuff that he did before, in the early 1980s, coalesces in “The Whistle Song” [1991], which is very string oriented, flutes. It’s happy. It’s emotional. It’s all in there, like a computer chip of Frankie Knuckles’s feelings.

A moment that always comes back to mind is when he was at what I would call his peak, in 1991, at Sound Factory. He was in the next phase of his career in terms of production and music. There was a lot of new stuff happening and he was a filter for that, a beacon. You felt like you were being taken to another realm of consciousness. That’s the best way I can put it. And there was a level of mastery there. It was a shamanistic kind of thing, like a shaman who wants to take you on this journey and these are the resources he’s using: vinyl, tape decks, MP3s, whatever, to sonically get you out of this world. So that’s what it was like to go hear Frankie Knuckles. It was out of space, brother [laughs].

Frankie’s music, his art, his style, everything, it talked to me. I was able to take that and then, through my own filter, develop my craft. The seeds that he planted sonically, through his emotions, everything else, they are why we—students of his, people that went to go hear him, people coming up under him—are following along this unseen spiritual thread he helped weave into the industry. His approach, his psyche, his emotions, and his energy are still here. As we know through science, energy doesn’t dissipate, it just changes form. It’s still floating around, you know. That’s why we’re having the conversation today.

—Ron Trent, as told to Antwaun Sargent

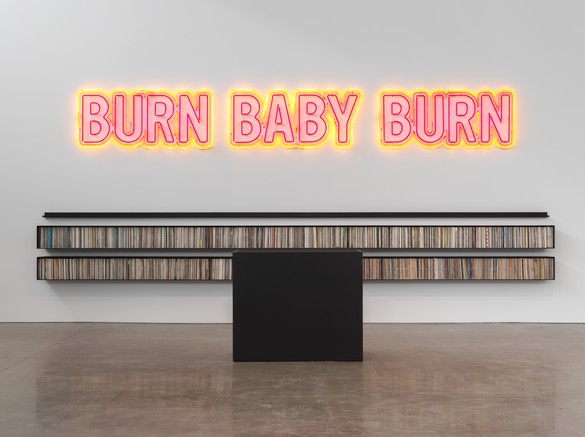

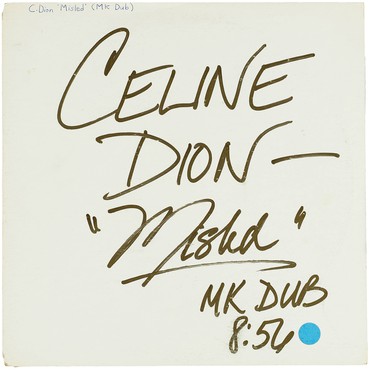

A selection of Knuckles’s record collection

Frankie Knuckles received his first number-one dance-chart hit, of an eventual four, with “The Whistle Song.” This early promotional copy of the track was released in 1991 and the song was included on Knuckles’s first full-length album, Beyond the Mix, later that year.

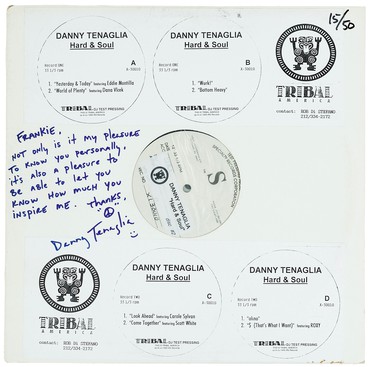

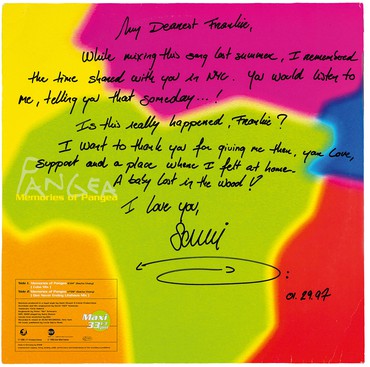

The community that cohered around Chicago house music eventually spread worldwide, but in the early days the dialogue and camaraderie between DJs, producers, and musicians created an intimate, symbiotic milieu. These two albums are just a few of the thousands of records in Knuckles’s collection showing handwritten notes that attest to this closeness and gratitude.

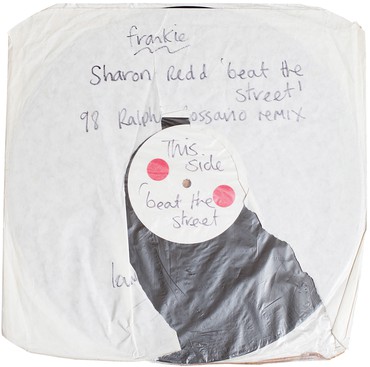

Knuckles marked some records with a blue or red dot. This method allowed him to flip through his crate and identify party-moving records quickly in a dark, smoky club. Red dots cued him to a hot groove, bringing the crowd to a fever pitch, and blue dots indicated grooves for cooling off the crowd. Mixing these hot and cold tracks in his own way made a party a frankie knuckles party.

These records are test pressings, manufacturing proofs made in limited quantities for the artist, A&R team, label reps, and DJs to review or test in clubs before the disk goes into production. Test pressings are special because some don’t make it to the mass pressing. The Celine Dion record is an acetate, meaning the grooves are cut into a hard acetate disc. These are made for reference only and are never for sale to the public. Acetates are sometimes produced directly from the recording studio and are tested in the clubs the same evening. They play like a normal vinyl record but their grooves will quickly wear and tear, limiting quality play time.

Another example of an early acetate record, this one laser etched with pictures and song lyrics by Baby Ford.

Photos: David Sampson, courtesy the Rebuild Foundation

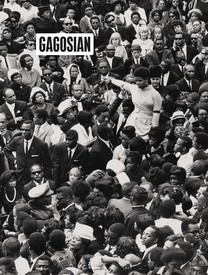

Social Works: Curated by Antwaun Sargent, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York, June 24–August 13, 2021

The “Social Works” supplement also includes: “Notes on Social Works” by Antwaun Sargent; “Lauren Halsey and Mabel O. Wilson”; “Carrie Mae Weems and Maya Phillips”; “Sir David Adjaye OBE”; “Allana Clarke and Zalika Azim”; “Rick Lowe and Walter Hood”; and “Linda Goode Bryant and DeVonn Francis”