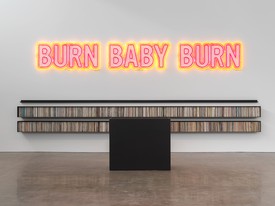

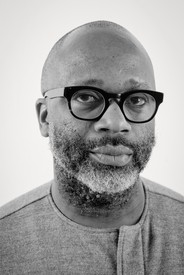

Theaster Gates’s practice traverses an extraordinary range, from collecting to social gathering, architecture and object making, experimental music and sound, and the ethical and physical reconstruction of civic life. His interdisciplinary fusion of archiving, performance, institution building, painting, and sculpting is deeply rooted in African American histories and cultures, and revolves around the transformation of objects, edifices, and communities through art and cultural activity. Photo: Chris Strong

Louise Neri has been a director at Gagosian since 2006, working with artists and developing exhibitions, editorial projects, and communications across the global platform. A former editor of Parkett magazine, she has authored and edited many books and articles on contemporary art. Beyond the exhibitions she has organized for Gagosian, she cocurated the 1997 Whitney Biennial and the 1998 São Paulo Bienal, among numerous international projects. Photo: Lin Lougheed

Louise NeriHow did Black Image Corporation come into being?

Theaster GatesBlack Image Corporation is a tribute to the Johnson Publishing Company, one of the most important Black publishing houses in the world. Johnson Publishing was founded in 1942 in Chicago and remained privately held and run by John H. Johnson until his death in 2005, publishing magazines such as Ebony and Jet as direct complements to Life and Reader’s Digest, which, while having broad circulation, did not cater to the interests of Black people.

The photographic archive of Johnson Publishing, which numbers over 4 million assets, was interesting to me as a body of work; redressing it as Black Image Corporation felt like a huge innovation. I was compelled to take this corporation, which was becoming less active, and create a new corporation.

LNAnd you proposed the idea of this new corporation as an active, migratory structure with no fixed place.

TGYes. In the introduction I wrote for the Prada exhibition in 2018, I outlined how the collection came to me in the same way as other material objects do—under duress, in distress, and in need of an immediate financial and logistical ally. I saw the opportunity that I could partner with Johnson Publishing—that an artist could redirect the value proposition of a Black corporation, or, rather, that artists could be directly involved in the thing called “business,” not for the sake of business alone but to actually capture the possibility of a greater cultural moment. To the outside world, the collection may have seemed to be in peril, but to me the photographic images were waiting on their next life—not as historical inventory to a contemporary publishing company but as extraordinarily valuable images that would reaffirm the power of both Black identity and Black business. Sometimes for me, the art part comes as a response or reaction to the crises that seem to pervade Black material culture and cultural production. How can we effectively intervene not only as artists but also as skilled negotiators, silent partners, and national strategists on behalf of important cultural legacies? Thus this work felt similar to other projects in that the Johnson Publishing archive was under duress, but different because what it needed from me was not necessarily an artistic response but a response that might look like conventional business.

LNI’d disagree that it was not an “artistic” response. First, you’ve described yourself not as a scientific archivist but as an artistic one, which gives you license not to be bound by technical rules and constraints. Second, very soon after your initial negotiations with Linda Johnson Rice, the Johnson Estate heir, you devised a strategy to reify and reenergize this valuable archive of Black cultural image-making and edification by presenting it in prominent cultural spaces, from the Fondazione Prada in Milan—the cultural arm by which one of today’s most media-savvy and sophisticated global fashion corporations maintains an intellectual soul—to venerable museums and arts institutions across Europe: the Sprengel Museum, Hannover, the Kunstmuseum Basel, the Gropius Bau, Berlin, and the Haus der Kunst, Munich. Your response is artistic because you’re using the spaces of art, to which you have access precisely because of your power and access as an artist.

TGSure, but what I’m suggesting is that the initial engagement required legal negotiating while staying mindful of the optics of the organization, as well as strategizing the dissemination of the images through the best possible platforms. This entailed being both an artist and something else. It was after creating Black Image Corporation—now a trademark brand and company name—that I could then return to being the artistic director of the Johnson Black Image Archive and become a creative partner to the work of Black photographers.

LNLet’s talk about your role as editor in your concept of artist. Within the huge cultural milieu that Johnson Publishing represents, you chose to focus on two key Black image-makers of the civil rights era, Moneta Sleet, Jr., and Isaac Sutton. Why?

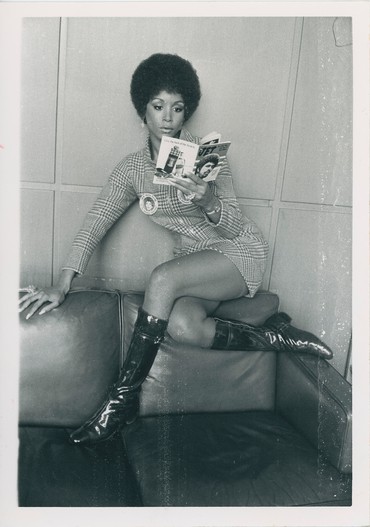

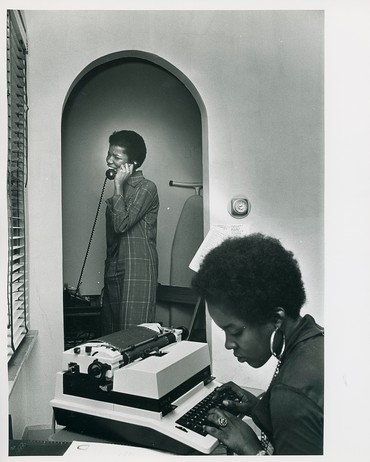

TGSleet and Sutton captured some of the most potent and searing images of Black political life. While thinking about the hope represented by Black beauty and fashion, between them they photographed some of the most beautiful and radically elegant women in the world. Having access to these images gave me permission to perform as a publishing house. Because Johnson Publishing owned these images, my artistic intervention was not directly on the images themselves; rather, my art was located in the form-making, whether corporate form or artistic direction as form. In this instance my choice of images focused primarily on Black women, femininity, the workplace, mothers, anomalies within the feminine, drag culture (1950s cross-dressers and the trans ballroom scene), and the idea of sacredness within the image itself, all under the unifying concept of “Black Madonna.”

LNHow did you work with the archive in practical terms?

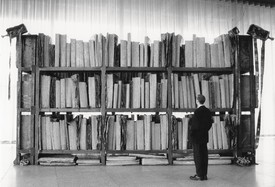

TGI got permission to use 20,000 images at my artistic discretion, and for each of these images to be reproduced once. To date, we’ve used approximately 5,000 of the 20,000 images. To have this permission has been very exciting, but it’s been even more exciting for me to create the platform through which these images might be disseminated. For example, the huge cruciform wooden cabinet that I made for the Kunstmuseum Basel was conceived as both a tool and a sanctum whereby people could look at Black images in a direct and intimate way. The cabinet was essentially a cabinet of Black feminine curiosities. We knew that many of the people engaging with the cabinet had never encountered Black women in such a frontal way. It was both an educational tool and an altar.

LNYou framed each print so that viewers could pick it up in their hands, using conservator’s gloves, and look at it closely. Thus you considered how to control and slow the process of perception itself.

TGExactly. One has to choose images from the cabinet’s racks; they’re not immediately accessible. A collective curatorial experience emerges when people gather around the cabinet and look closely at the archive.

LNIn a second iteration at the Osservatorio in Milan you produced individual, lecternlike cabinets. Did this change the way people approached the act of looking at the images?

TGYes. I conceived the lecterns as “stations” to allow individuals to have their moment with the Black image—in this case, the sacred presence of Black women.

LNIs there a relationship between Black Image Corporation and the upcoming New York exhibition Black Vessel?

TGBoth Black Image Corporation and Black Vessel have legal structures that help substantiate and legitimize, respectively, the reproduction of images and the activity of brick manufacturing. I take this work very seriously. It’s also significant to me that both projects engage the ways in which gathering, convening, or cooperation allows for a more ambitious activity to occur, one that goes beyond the actions of a single individual.

Finally, Black Image Corporation and Black Vessel deal with histories that have both national nostalgia and individual sentimentality—using the core memories of, say, looking at a Jet magazine or playing with mud in Mississippi to exhume a conceptual foundation.

LNCan you elaborate?

TGDuring the last nine months I’ve been reflecting on the things that matter most in my practice. There’s a material essence, a conceptual foundation, and a social, spiritual dimension. Black Madonna accesses this social, spiritual dimension, so for the past nine months I’ve also been pursuing that idea in my studio. In addition to making works of art, the question of the sacred remains very important to me. I’ve been asking myself whether it’s possible to convert a place of commerce into a sacred space.

LNDoes the fact that the Johnson Publishing archive was recently acquired by a consortium of four leading American philanthropic foundations—the Ford Foundation, the Mellon Foundation, the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the MacArthur Foundation—change how Black Image Corporation will function in the future?

TGI’m glad the images have a home. I’m glad to have had my encounters with the archive and that my encounters will continue.

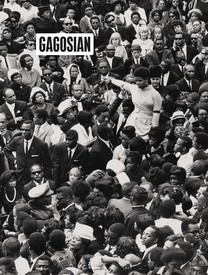

LNCan you say more about your interest in Moneta Sleet, Jr., who photographed the image of the public funeral of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that appears on the cover of the Fall 2020 edition of the Quarterly? [Editor’s note: Sleet won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969 for his iconic image of King’s veiled widow and daughter in the church on that same day.]

TGSleet’s legacy felt underappreciated to me, so my project with him was an opportunity to celebrate not only the Johnson Publishing Company but the artist himself.