Jed Perl was the art critic for The New Republic for twenty years and a contributing editor to Vogue for a decade. He is currently a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books. Among his many books are Calder: The Conquest of Time, Magicians and Charlatans, Antoine’s Alphabet, New Art City, and Paris Without End. He has written for Harper’s, The New Criterion, The Yale Review, Salmagundi, and many other publications. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and teaches at the New School in New York. Photo: Duane Michals

When Alexander Calder died, in 1976, at the age of seventy-eight, his old friend Saul Steinberg saluted him as “a dancing man.” The artist, known to everybody as Sandy, loved to improvise on the dance floor, preferably to the beat of a jazz band or one of the samba records that he and his wife, Louisa, had picked up in Brazil. Calder’s fascination with dance takes us to the heart of his revolutionary reimagining of sculpture. His mobiles move through time and space: that’s what dancers have done from time immemorial. It’s no wonder that all through his life Calder pursued any and all opportunities to embrace the art of dance. A belly dancer by the name of Fanni was one of the attractions in the miniature Cirque Calder that he began performing for small audiences in Paris in the late 1920s. In the succeeding years he worked with choreographers and musicians in the theater and produced a number of versions of what he called a “ballet without dancers.” This alphabet presents some glimpses of Calder’s lifelong engagement with ballet as well as many other forms of dance and theater. Much of the material comes from my biography of Calder; the second and final volume, Calder: The Conquest of Space, was published by Knopf in spring 2020.

A

Amériques

The avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse, whose startlingly percussive compositions earned him a special place in the history of modern music, became friends with Calder in the early 1930s. From the Calders’ home in Paris, Louisa wrote about Sandy and Edgard’s friendship in a letter to her mother: “Sandy is working downstairs, and talking to Varèse, the composer whose music corresponds to Sandy’s wire abstractions, so he likes to watch him work.” What connected these two creative spirits? The composer’s fascination with what he called the movement and collision of “sound-masses” had aural analogies with the way the sculptor used forms to “compose motions.” The search for affinities between sound and sight went back to the late-nineteenth-century Symbolists and their fascination with synesthesia. In 1971, six years after Varèse died, Calder saluted the dreams they had shared when he designed sets and costumes for a ballet set to Varèse’s Amériques, a symphonic composition with an enormous percussion section and the screeching sound of a siren.

B

Balanchine

Although Calder and George Balanchine, by most estimates the greatest ballet choreographer of the twentieth century, never worked together, they knew each other to some degree. Both men joined an old-world grace and elegance with a very American feeling for speed and muscularity. On a few occasions a collaboration seemed to be in the offing. Lincoln Kirstein, who brought Balanchine to America and worked with him to set up a school and a company, may have sensed some affinity when he took the choreographer to see Calder’s first show at New York’s Pierre Matisse Gallery in April 1934. “Balanchine thought he might make fine décor for ballet,” Kirstein wrote in his diary. “Great big toys.” The following October, there was a meeting between Calder and Balanchine. Again, the evidence is in Kirstein’s diary: “Sandy Calder into the School [of American Ballet] with designs for a ballet on a pad of paper. A great red heart-like shape, and his mobiles shooting around. I thought it might be nice but Balanchine said it was too close to [Joan] Miró’s Jeux d’Enfants,” a ballet, with choreography by Léonide Massine, mounted in Europe two years earlier. In 1946 or 1947, Kirstein again had conversations with Calder about doing sets or costumes, but again it came to nothing. Flash forward to the early 1970s and a French friend of Sandy and Louisa’s, in New York on a visit, stopped by the Perls Galleries on Madison Avenue; the Calders used one of the upper floors of the gallery as a pied-à-terre when they were in the city. She was told that Calder was upstairs in a meeting. When the door of the upstairs office opened, there were Calder and Balanchine. They were almost certainly discussing the possibility of bringing to the New York City Ballet the “ballet without dancers,” entitled Work in Progress, that Calder had mounted at the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma a few years earlier, in 1968. Although Work in Progress was never performed in New York, we know from correspondence that Calder wasn’t averse to having the original electronic score, by three contemporary Italian composers, replaced with something by Balanchine’s great friend and collaborator Igor Stravinsky.

C

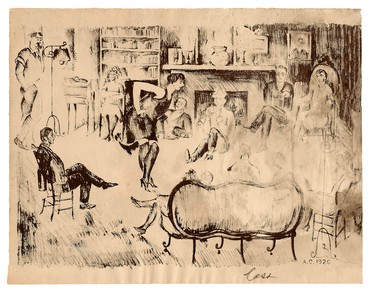

Charleston

The year 1926, when Calder first arrived in Paris, is generally seen as the year when the Charleston, the dance that defined the Roaring Twenties, reached the height of its popularity. Something of the breakaway beauty of the Charleston can be felt in the work that Calder did for the next fifty years. In a lithograph that he made in New York before leaving for Paris, Florence King (whom her husband, the art dealer Carl Zigrosser, called an “athletic feminist”) entertains a group of their friends in a Greenwich Village apartment by stepping into the middle of the living room and kicking up her heels in an explosive rendition of the Charleston.

D

The Dancer and the Dance

Among the speakers at Calder’s memorial service, held at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art on December 6, 1976, a month after his death, was his great friend the critic, curator, and museum director James Johnson Sweeney. Sweeney had the deep, melodious voice of a Shakespearean actor or a Roman orator. He closed his panegyric by invoking William Butler Yeats’s poem “Among School Children” as he proclaimed: “Though the dancer has gone, the dance remains. You have left us happiness not sadness, Sandy—miss you as we must.”

E

Ellis

Calder’s father, the sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder, was a great admirer of the social reformer Havelock Ellis, whose Dance of Life (1923) he counted among his favorite books. I feel pretty sure that Calder too read this book, in which the art of dance is related to the rhythms of life and the universe, which Calder was harnessing when he made sculpture move. “Dancing and building,” Ellis writes, “are the two primary and essential arts. The art of dancing stands at the source of all the arts that express themselves first in the human person. . . . The significance of dancing, in the widest sense, thus lies in the fact that it is simply an intimate concrete appeal of a general rhythm, that general rhythm which marks, not life only, but the universe.”

F

Folk

In 1958, the very first year of the Festival dei Due Mondi in the Italian city of Spoleto, Calder was commissioned to create sets for The Glory Folk, a ballet by a young American choreographer, John Butler, who had earlier danced with Calder’s old friend Martha Graham. Spoleto was a tremendously exciting place that summer, what with the inauguration of a festival designed to celebrate fresh cultural collaborations and alliances between Europe and America. The theme of The Glory Folk was American evangelical experience. Calder’s set took the form of a red stabile with gothic arches, suggesting a place of prayer, and a silvery mobile that, as the artist wrote, evoked “revelation.” The dancers reached out to the mobile, their arms extended in gestures of religious striving and yearning. Calder ordinarily took no interest in organized religion. The Glory Folk was one of a small number of occasions when he seemed to at least consider the possibility that the art of the mobile could suggest transcendence and maybe even the ineffable. Chandler Cowles, one of the people involved with The Glory Folk, wrote to Calder, “I can hardly wait to see the effect of your ‘Holy Ghost’ when it reveals itself in Spoleto.”

G

Graham

Calder and Martha Graham were lifelong friends. In the mid-1930s, when Graham was already recognized as the preeminent modern-dance choreographer of her time, she worked with Calder on elaborate sets for two dances. Years later she would remember the famously informal Calder arriving in Bennington, Vermont, where the first of these collaborations was mounted, wearing “nothing but his undershorts.” For the Bennington dance, an elaborate survey of American history entitled Panorama, Calder created mobile elements hung over the rafters in the Vermont State Armory. The plan was for the dancers to manipulate Calder’s creations as they moved around the stage, but the critics found Calder’s interventions arbitrary. The response was no better in New York, where Graham presented her second collaboration with Calder, a dance called Horizons. In the New York Telegraph, Calder’s contribution was ribbed as “a series of floating balloons, ropes wriggling like sleepy snakes, and something that resembled a huge turnip.” Graham, herself a great adventurer, was interested in Calder’s adventures. The dance critic Arlene Croce once called a Graham solo, Lamentation, “solid geometry as live emotion”; that could double as a description of some of Calder’s work. But in the face of a critical press and the technical foul-ups that dogged Calder’s mobile sets, Graham must have concluded that she needed to look elsewhere for a collaborator. She found what she wanted with another friend of Calder’s, Isamu Noguchi, who over the years created for Graham an extraordinary succession of stage designs. But Calder was there at the beginning. He worked with Graham on Panorama within months of Noguchi’s first outing with her, a setting for Frontier.

H

Harvard

In 1930, Calder was invited to exhibit at the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, a pathbreaking art center organized by Lincoln Kirstein, then still an undergraduate at the college, and a few of his friends. By the time, decades later, that Kirstein was recalling his Harvard days in a memoir entitled Mosaic (1994), he had pretty much rejected abstract art, but he described Calder’s appearance in Cambridge as among the “few golden hours” of the Harvard Society. He singled out the theatrical chops that Calder brought to a performance of his Cirque Calder, which began, “unforgettably, before the show, with sly, self-deprecating ingenuity [as] he padded through his audience handing out peanuts.” That little salute to Calder’s gifts as a performer is a high compliment, coming from one of twentieth-century America’s supreme connoisseurs of the theatrical arts.

I

Ives

In 1975, the year before he died, Calder produced costumes for Mobilissimo, a ballet by René Goliard set to music by Charles Ives, whose bold modern vision embraced the sights and sounds of an older America. A Le Monde critic judged the ballet a failure, but did say that “the décor, Calder’s jerseys, very colorful, go wonderfully with the facetious music of Charles Ives, music that evokes an America of fairs, military parades, ice creams, and football games.” Calder never said much, at least not that found its way into print, about his taste in modern music. But he may have felt some affinity with Ives, another genius who admired Yankee ingenuity.

J

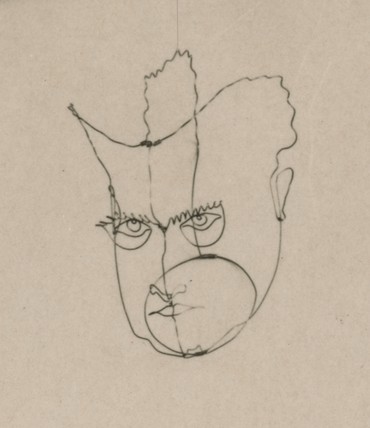

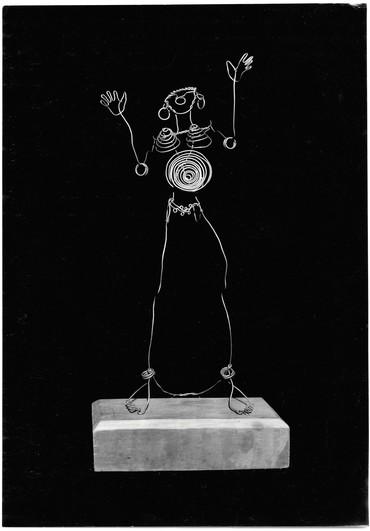

Josephine Baker

Calder said that he never actually saw a live performance by Josephine Baker, the great African American dancer who was the toast of Paris when he arrived there in 1926. Maybe not, but in photographs and films of this long-legged, riotously funny queen of the Paris cabarets, Calder discovered an American original who inspired some of the earliest and choicest of his wire sculptures. The dance critic André Levinson described Baker as a “sinuous idol . . . there seemed to emanate from her violently shuddering body, her bold dislocations, her springing movements, a gushing stream of rhythm.” Working with curves, curls, and spirals of wire, Calder produced a number of portraits of Baker. He reimagined her performances as mobility incarnate. His lengths of wire became calligraphic lines of force careening through space.

K

Kleist

In 1811, the German romantic writer Heinrich von Kleist published his essay “Über das Marionettentheater” (On the puppet theater). It is a curious piece of prose, arguably not so much an essay as a short story or maybe even a fable. The author, staying in a small town, has noticed a famous dancer watching a marionette show in the town’s fairground. When they fall into conversation one day, the narrator expresses surprise at the dancer’s fascination with this rather crude bit of theater. The dancer doesn’t find it crude at all: there is, he explains, a purity and even a spirituality in these humble marionettes, a quality he finds lacking in the movements of most dancers. Grace, the dancer explains, appears “most purely in that bodily form that has either no consciousness at all or an infinite one, which is to say, either the puppet or the god.” The string that connects the puppet to the puppet master strikes him as suggesting “nothing less than the path of the dancer’s soul.” While there is no way to know whether Calder knew Kleist’s essay, the dancer’s words help us grasp the power of Calder’s grandest mobiles of the 1940s and 1950s. Those unprecedented sculptural inventions, with their arrays of metal elements, are suspended from the ceiling by a single string that allows inanimate forms to take on a life of their own—as pure, as graceful, and (dare I say it?) as soulful as the marionettes that held the attention of a dancer in a little German town in the early nineteenth century.

L

Léger

Calder’s fascination with a union of the visual and the theatrical arts had roots deep in the nineteenth century, when Richard Wagner brought together a range of creative spirits in what he dubbed the Gesamtkunstwerk—the total work of art. Soon afterward, the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev, an aficionado of all things Wagnerian, asked composers, choreographers, and dancers to collaborate with a host of European artists, including Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, in the productions of his Ballets Russes. It’s unclear what Calder knew of the work of the Ballets Russes, which folded with Diaghilev’s death, in 1929, three years after Calder arrived in Paris. But he certainly felt the afterglow of Diaghilev’s work, through various companies that echoed and built on the Russian’s achievement. I’m convinced that Calder was familiar with the sets that Picasso designed for Mercure, a ballet with music by Erik Satie and choreography by Massine that premiered in 1924 with a rival company, the Soirées de Paris; those sets, with their rattan image of a horse and rider, are somewhere in the prehistory of Calder’s wire sculptures. We know that Calder saw Jeux d’enfants, with music by Georges Bizet, choreography by Massine, and sets by Calder’s friend Miró, because Kirstein reported seeing him (and Noguchi) at a performance in Paris in 1933. Calder couldn’t have attended the ballets Skating Rink and Origins of the World, with which another great friend, Fernand Léger, was involved; they were mounted by the Ballets Suédois before he came to Paris. But there are enough echoes of Léger’s work in Calder’s designs for his own triumphant experiment in Gesamtkunstwerk, Work in Progress, that I am left wondering if he didn’t know, at least from photographs, some of what Léger had done for the Ballets Suédois. What is certain is that Calder’s most ambitious theatrical adventures are episodes in a history of the Gesamtkunstwerk that also involves the Symbolists of fin-de-siècle France, Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, and the theatrical experiments of the Russian Constructivists, the Dadaists, and the Bauhaus.

M

Massine

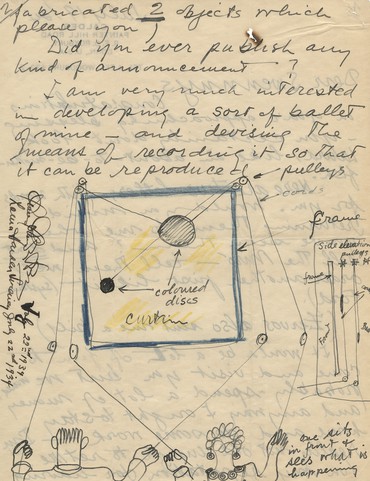

In Paris in the spring of 1933, Calder received a studio visit from Massine, the dancer and choreographer who, in the wake of Diaghilev’s death, aimed to build on his legacy with a new company, the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo. Massine had a huge reputation; he had thrilled audiences with his brilliant comic cancan in La boutique fantasque (1919) and had collaborated with Satie and Picasso on Parade (1917), the striking invention that brought Cubism’s discombobulating juxtapositions into the world of ballet. Calder was hoping to persuade Massine to let him mount what he was already calling a “ballet without dancers” for the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo. Among the works Massine probably saw in Calder’s studio was what the artist referred to as A Merry Can Ballet. Calder described this as “an abstract ballet using a frame with rings in the 2 top corners through which strings passed from the hands to the objects—springs, discs, a weight with a little pennant.” There were also some tin cans—thus the punning title. For some while after Calder and his wife returned to the United States, in 1933, there was talk about his returning to Europe to work with Massine. As late as 1937, a reporter in Time magazine commented that he “wanted to make enormous enlargements of his bobbling Mobiles to be the background for a modern ballet.” The truth was that he wanted his mobiles to become the ballet. Massine, though, could not see his way to a stage without living, breathing dancers. “Massine,” so a friend of Calder’s recalled years later, “insisted that there should be dancers on stage.” He was, after all, a dancer himself.

N

Nineteen Minutes

It was Calder’s great Italian friend the curator and critic Giovanni Carandente who helped him to realize his dream of a ballet without dancers at the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma in 1968. Calder decided to call it Work in Progress, but as he and Carandente were working out the details in Rome, he commented that what the work, with its enigmatically autobiographical elements, really ought to have been called was My Life in Nineteen Minutes.

O

Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress

This book of essays about James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, which was known as Work in Progress in the years before its final publication, in 1939, appeared in Paris a decade earlier. Among the essays is one by Robert McAlmon, whose circles overlapped with Calder’s, entitled “Mr. Joyce Directs an Irish Word Ballet.” During Calder’s years in Paris, ballet was becoming a metaphor for a new kind of freedom in the arts. McAlmon goes to the heart of that trend: “Music and the ballet are less inhibited by the demands of meaning than literature has been,” he writes. “Audiences do not insist upon a story or a situation to appreciate the movements of a dance or the strains of music. Critics allow that there can be a pure art in these mediums; they have sometimes come to permit with painting, sculpturing and architecture, that for evoking a pleasurable emotion or sensation, form and colour does not have to be utilitarian, descriptive, literal or possessed of meaning other than the intent to awaken response. Also good comedy, clowning, pantomime, nonsense, slapstick, drollery, does not appeal to the sense of humour by explanation but by gesture. In such good dances or music as are humorous, it is rarely possible to define the reasons for the comic appeal. Prose too can possess the gesticulative quality.” If Joyce created an “Irish Word Ballet,” Calder created what he called A Merry Can Ballet. Calder had probably met Joyce. He certainly knew Joyce’s daughter, Lucia, who wanted to be a dancer and briefly took art lessons with Calder; there is reason to believe that she was a little in love with him. And Calder’s great friend and supporter Sweeney—we have already heard him speak at Calder’s memorial service—was very much a part of Joyce’s circle in Paris in the 1930s.

P

Provincetown Players

For a few weeks or months in 1924, when Calder was still studying at the Art Students League in New York, he worked as a stagehand at the Provincetown Players, perhaps the most exciting experimental theatrical group then operating in the United States. The man he took orders from was Cleon Throckmorton, a towering figure in early-twentieth-century stage design. In a letter to his sister, Peggy, who was living on the West Coast, Calder wrote of “my venture into the theatrical business. I guess mother told you that last week I worked every night down at the Provincetown Playhouse shifting scenery. It was rather fun.” Throckmorton was famous for dramatically lighting the stage, so that the actors sometimes appeared almost as silhouettes. The play of light and shadow would always mean a great deal to Calder. There may be echoes of what amounted to Throckmorton’s light shows in the ghosts and doppelgängers that Calder’s wire figures and abstract mobiles create as their shadows move through a space.

Q

Quartet

In 1938, hoping that somebody would commission a large-scale kinetic sculpture from him for the New York World’s Fair, Calder created three maquettes. In each—one was later titled Dancers and Sphere—four differently configured forms are set on a single base and engineered so that each object moves in its own particular way. Years later Calder laughingly confessed to an interviewer that “nobody ever looked at them.” What he did manage to create for the World’s Fair was what he called his Water Ballet, a group of water jets engineered to go off at different times in different ways. The work was set up, at the entrance to the fair’s Consolidated Edison building, but whether it was ever fully operational isn’t clear. A version was resurrected in 1956 for the General Motors Technical Center in Michigan. Five years later, with The Four Elements mounted outside the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Calder finally realized at full scale one of the four-part inventions that nobody had been interested in back in 1939. One element in The Four Elements suggests an abstraction of a dancing figure, a triangular conical apparition with arms as if draped in some sort of robe. The other elements in this richly colored work are a column composed of semicircles, a disk mounted on a striped pole, and a lozengelike shape made of two intersecting arcs. These singular forms, propelled by hidden motors, create a comic dance performance, though the comedy is closer to the gravitas of Buster Keaton than to the giggles of the Marx Brothers.

R

Roxbury

People never stopped talking about the dance parties that Sandy and Louisa Calder organized at their home on Painter Hill Road in Roxbury, Connecticut. Rob Cowley, son of the Calders’ close friend the writer Malcolm Cowley, still remembers a party he attended in the summer of 1950. The night began mildly enough with spaghetti in the Calder kitchen. The entertainment was provided by none other than the famous stride piano player Willie “The Lion” Smith, along with “a pudgy clarinetist” named Cecil Scott. The teenager, already beginning to be interested in jazz, was awestruck by Smith. Meanwhile, Louisa was “set[ting] her ample hips in motion” and Sandy “was swinging a woman with surprising grace for a big man.” A little later, “Sandy had donned an outlandish Carmen Miranda–like headdress and was doing his version of the rhumba.”

S

Samba

Never to be forgotten by the guests at the Calders’ parties in Roxbury were the Latin records and the Latin dances, the Calders’ beloved samba, which had what Calder called a distinctive “shuffle,” the body gliding sensuously, the arms probably doing something ornamental in the air, the variety of movements perhaps not unlike the movements of a mobile. The samba came into Sandy and Louisa’s world with their first trip to Brazil, in 1948, when Rio de Janeiro was full of dance clubs where people learned the new songs and dances in the months leading up to Carnival. In 1960 the Calders finally fulfilled their dream of seeing the Rio Carnival itself. The poet Elizabeth Bishop—who was living in Brazil with her lover, Lota de Macedo Soares, both friends of the Calders’—described Sandy and Louisa as thrilled by the festivities and undaunted by a night of rain: “The beautiful Louis XV costumes were all draggled, but they danced on until dawn. Calder stood up and watched for six hours. He is made of iron like one of his own creations, I think.” Another friend whom the Calders encountered in the midst of the festivities, the architect Frederick Kiesler, described Calder “in the jolliest of moods, with friends. We drowned in his energy, his continuous dancing and swirling and twirling.”

T

Thomson

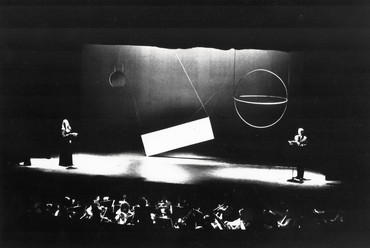

In 1936, the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, one of the first American museums to embrace the avant-garde innovations emerging in Europe, mounted a festival of the arts. Two years earlier, the opera Four Saints in Three Acts, with a libretto by Gertrude Stein and music by Virgil Thomson, had had its premiere at the Atheneum, a now legendary event that Sandy and Louisa had attended. For the 1936 festival, Thomson mounted a production of Satie’s chamber opera Socrate, a setting of excerpts from the Platonic dialogues, concluding with Socrates’s death. It was performed on the same bill as a new ballet by Balanchine, Serenata: Magic, choreographed to music by Mozart and with decor by the Neo-Romantic painter Pavel Tchelitchew. Calder designed the set for Socrate, an exquisitely austere combination of circular and rectilinear forms. Years later Thomson would say that Calder’s work had “long remained in my memory as a stage achievement.” He described a sphere and a disk moving slowly across the stage, and he remembered how, as the singers recounted Socrates’s end, a rectangular form, initially white, turned to become entirely black—something, as Thomson said, “stele-like.” Never before and perhaps never since were the essentials of Calder’s art—the pull of gravity, the flux of movement, the rising and falling forms—so deeply tied to questions of life and death, the connection unspoken even as the words were spoken. Who could doubt that a work about the death of Socrates had a particular resonance in 1936, when the Europe of creative, exploratory thought was already dead in Germany and dying in so many other places? “Attention to words and music had not been troubled,” Thomson wrote thirty years later of Calder’s setting, “so majestic was the slowness of the moving, so simple were the forms, so plain their meaning.”

U

Urbanism

In Calder’s later years the lion’s share of his energy went into creating monumental sculptures for public spaces. The dance critic Edwin Denby, whom Calder knew slightly, once gave a lecture entitled “Dancers, Buildings and People in the Streets”; Denby’s feeling for urban life as theatrical drama—a drama that took different forms in different times and places—was something that Calder definitely shared. The artist regretted, so he told an old friend, that “most architects and city planners want to put my objects in front of trees or greenery. They make a huge error. My mobiles and stabiles ought to be placed in free spaces, like public squares, or in front of modern buildings.” He saw his larger works as elements in the urban drama; when he imagined a setting for one of his monumental sculptures, he wanted it to function as what he called “a real urban signal.” Nowhere is that drama more beautifully fulfilled than in the Federal Center in Chicago, where three dark, almost saturnine buildings by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe define the plaza and Calder’s brilliant red Flamingo (1973) provides an ebullient, explosive counterpoint. At any time of day, the plaza is filled with men and women in motion; they become dancers in the urban dance, defining and redefining the dynamics of city life.

V

Valentin

For his first show in New York with the gallerist Curt Valentin, in 1944, Calder exhibited works made in plaster and then cast in bronze, a medium he used only rarely. His bronzes were like nothing done in the medium before: they were works with multiple parts, the elements pivoting one atop the other, so that this most stolid and earthbound of mediums achieved some of the buoyant, kinetic quality that gallerygoers already knew from Calder’s mobiles. Among the most striking of these objects was Dancer, a sculpture in four parts: a base consisting of one massive leg, on which are mounted three elements that together comprise the other leg and the torso, the breasts, and, finally, the head and the arms. When given a gentle shove, Dancer, a ballerina who doubles as a comedian, gently circulates and rises up and bends down. In the context of Valentin’s gallery, where Degas’s sculptures of ballerinas were seen from time to time, Calder’s Dancer must have struck viewers as an evolutionary leap—Degas’s frozen motion reanimated.

W

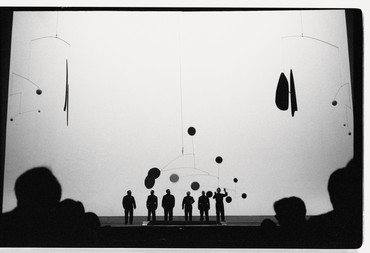

Work in Progress

In 1968, when Calder finally got a chance to put together the “ballet without dancers” that he had been dreaming of for close to forty years, he filled the stage of the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma with standing and hanging mobiles, colorful birds and sea creatures, cyclists doing figure eights, and a man waving a red flag. The music was by three young Italian composers who combined electronic sounds with more conventional orchestral instruments. Work in Progress was the story of Calder’s life, but told in signs and symbols. It was also an exploration of the origins of life; and before all that it was the culmination of a lifelong fascination with dance, music, drama, and theater. Opinion at the premiere was divided: a critic in the London Daily Mail reported that “glittering guests gasped with horror at Alexander Calder’s Work in Progress,” but the novelist Alberto Moravia told Newsweek, “As a sculptor he realized a great sense of theater. It was done with delicacy, with elegance, or maybe the word I mean is magic.” That this spectacle was mounted in Rome sets me to thinking about Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the preeminent sculptor of the Roman Baroque, who had been as fascinated by the theater as Calder would be three hundred years later. The English visitor John Evelyn wrote in 1644 that Bernini, “a little before my coming to the city, gave a public opera (for so they call shows of that kind), wherein he painted the scenes, cut the statues, invented the engines, composed the music, writ the comedy, and built the theater.” That would pretty neatly describe what Calder brought off with Work in Progress.

X

Xylophone

Among the many percussion instruments that Earle Brown assembled for Calder Piece, first performed in Paris in 1967, were glockenspiels, marimbas, cymbals, temple blocks, xylophones, vibraphones, cowbells, congo drums, and tom-toms. At the center of the action was a standing mobile, Chef d’orchestre, that Calder had created especially for the occasion. The four musicians moved between their percussion instruments and Calder’s mobile, which became a percussion instrument as they raced (in a sense danced) around it. The critic Dore Ashton caught some of the comic, almost Keystone Cops craziness of a performance of Calder Piece. She was amazed at the way that “as the mobile gains momentum, the musicians accelerate their movements until they are literally running, producing an extraordinary visual effect as they chase and sound the bobbing red forms. Here, the synesthetic element, cherished for more than a century, is in full play. The rhythms produced by the mobile, swinging wildly into space, and the players who must keep pace, are rhythms that are endemic to both arts, visual and musical, and that are joyously tapped by the composer for expressive perceptions.” The art critic Pierre Descargues, writing shortly after the premiere, put the whole mad adventure in a nutshell: “It is a ballet and a game.” Silly and serious, simultaneously comically simple and crazily complex, Calder Piece was Calder, nearly seventy at the time, doing cartwheels with an avant-garde composer some thirty years his junior.

Y

Youth

Pageants and spectacles of all kinds had fascinated Calder since he was a boy. When he was nine, his family lived in Pasadena, California, where he was thrilled by the Tournament of Roses. His sister would particularly remember a float with “a peacock constructed wholly of white flowers, with the tail made entirely of unbelievably fragrant lilies of the valley.” She would also recall that the morning after the tournament, Calder was already busy sawing at six-thirty, making “horse heads from an old wooden box and hammering them onto handles—Mother just managed to save the handle of her new broom.” These horses were mounted by the local children for jousting matches. Then Sandy proceeded to make chariots out of orange crates. What his friend Sweeney called Calder’s lifelong interest in spectacle began very early.

Z

Zarathustra

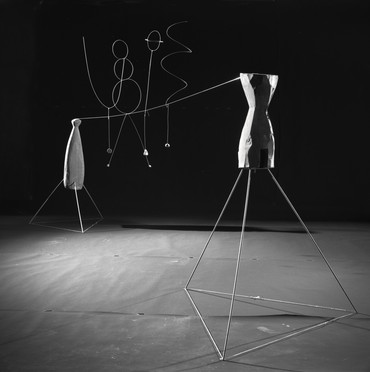

In Tightrope (1936), four enigmatic abstract acrobats are suspended on a long wire. When the wire is plucked, Calder’s spectral tightrope dancers are set in quivering life, each vibrating in its own way. For the photograph that Calder’s friend Herbert Matter made a few years after Tightrope was completed, he set the sculpture in a darkened space, where the abstract forms, like actors illuminated on a stage, suggest the protagonists in an archaic drama. They bring to mind Nietzsche’s words about the tightrope and the tightrope walker in Thus Spake Zarathustra: “Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman—a rope over an abyss. A dangerous crossing, a dangerous wayfaring, a dangerous looking-back, a dangerous trembling and halting. What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal: what is lovable in man is that he is an over-going and a down-going.” Any man or woman is a tightrope walker—an acrobat, a dancer—crossing an abyss.