Fan Jingzhong is an art historian and a professor at China Academy of Art, Hangzhou.

In an essay titled “The Classics and the Man of Letters,” the English writer, critic, and poet T. S. Eliot makes an argument that can be summarized as follows: there are some people who regard anything new with disdain and struggle to see its merits, and there are other people who see anything old as a worthless eyesore. These prejudices serve to dramatize the hoary solemnity of old things and the strangeness and even deceptiveness of new things. They also form the context in which contemporary art is created.

I

It is this context in which Hao Liang’s artworks leave an intense impression on us. He obsessively studies the classics while striving resolutely to blend the old with the new. He even draws on ancient texts when choosing titles for his works. His paintings are not illustrations of these titles, nor do the titles describe the content of the paintings. The paintings and titles are independent and parallel: sometimes complementary, sometimes divergent. He is more concerned with the modern expression of classical concepts than with the aesthetic effect of his paintings, and he seems to remain engaged in constant philosophical discourse with the Western Surrealist painter René Magritte.

Magritte’s works can generally be appreciated in two ways. The painter often put completely different objects together in unexpected ways, while also positioning similar objects in surprising juxtapositions. Isolation, embellishment, coincidence, visual puns, paradoxes, and conceptual polarization are among the many elements of Magritte’s visual arsenal.

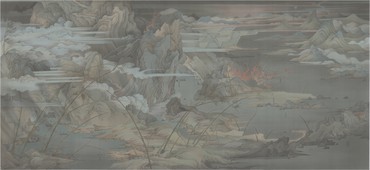

Hao Liang uses similar expressive methods with more expansive implications. The title of his recent work Eight Views of Xiaoxiang (2014–16) refers to a specific set of tableaux in the Chinese painting tradition: wild geese on sandy beaches, distant sails on the horizon, a mountain temple shrouded in sunlight and mist, twilit scenes of snowy rivers, an autumn moon over Dongting Lake, a rainy night in the Xiaoxiang region, the evening gong at the misty Qingliang Temple, the sunset over a fishing village. These original eight scenes can be traced back to the Song dynasty literatus Song Di (1015–1080), whose poetical descriptions of these scenes have survived even though a complete set of his paintings has not. It is these descriptions that Hao Liang chose to adopt as titles for this series of paintings, though he did not paint the corresponding set of scenes. In his appropriation of the titles, Hao Liang disregards the corresponding images while seeking to explore the descriptions themselves. Song Di’s “Eight Views of Xiaoxiang” differs from both an untitled poem cycle by Li Yishan (813–858) and “Autumn Meditations,” an autobiographical work by Du Fu (710–770). The sequence of Song Di’s titles has its own sense of order, and Hao Liang seeks to remind us of the ancient connotations of Song Di’s original titles:

The clear and bright scenery has passed, the dusk advances like months and years in an unsettled heart, and human life vanishes into a void that leaves no trace. The secrets of ensuring a happy life lie in the joys of sensory experiences: the sights of the autumn moon over Dongting Lake and wild geese landing on a sandy beach are delights that can alleviate one’s frustrations. Even glimpses of distant sails on the horizon and twilit scenes of snowy rivers contain a kind of courage, for these glimpses incite within one an incisive sensation like falling snow that does not linger in the air; and perhaps the evening gong at the misty Qingliang Temple and the sunset over a fishing village are a kind of visual koan akin to the final line from Zuo Si’s (250–305) “Miscellaneous Poem”: “The strength of youth is fleeting, the end of life is often wistful.”

Thus the “Eight Views of Xiaoxiang” transcend physical space and appeal to people’s senses and sentiments. They are less concrete than the “Ten Scenes of West Lake,” and more scintillating. This scintillation contributes to their ephemerality, like a pear blossom glimmering in the moonlight. The poet Su Dongpo (1037–1101) wrote three poetic inscriptions for Song Di’s Xiaoxiang paintings, the first verse of which ends in an illustrative line: “A guest from Hengyang comes / to view these misty notions.”

In his paintings, Hao Liang draws on these “misty notions” to explore realms that are only tangentially related to the original eight scenes. His mind’s eye resonates with nature, and when nature is turbulent, his heart leaps into action:

When the early spring moon appears

Explore its color

Compare its type

The magnificence of spring flows forth from frozen surfaces and sways in the lengthening shoots of bamboo. The fine snow departs from the sky as if to extol a yet greater wonder. The distant peaks climb into gem-like white clouds, thickly swirling, gently singing in a voice inaudible to our ears. The rocky mountains form towering peaks, imposing cliffs, and majestic peaks, like Fan Kuan’s (960–1030) sketches; or steep hills and rolling hillocks, like Wen Zhengming’s (1470–1559) paintings. These paintings by Hao Liang, composed exclusively with classical brushwork techniques, depart from the dry and bright Eight Views of Xiaoxiang by Muqi Fachang,1 and his imagery differs from that of Mi Fu’s (1051–1107) vivid and saturated approach. Hao Liang creates a dual-layered distance that recalls Xu Xiake’s (1587–1641) blend of vision and thought: “I have learned not to fixate upon the vague firmament above me, nor the nuanced depths of my own inner world, nor the disorderly temptations of the human world; instead, I open my eyes wide and think by moving my feet . . . transcending my flesh and blood, I press forward in the face of danger.”

Hao Liang uses his brush to subtly indicate the footsteps of humankind through this dangerous and difficult terrain. Spring water gushes from a hillside beside the ruined walls of the Wangchuan Villa. We seem to see the ancient Tuo, Yong, Fen, Yangtze, Han, and Ru Rivers in this painting, the dangerous depths and exposed shallows of which pedestrian travelers like Xu Xiake likely had to wade through on their journeys. A wildfire flickers in one of the paintings, Scholar’s Traveling, but we cannot discern whether it is fueled by the underwater music of the desolate wilderness or by the branches crashing together in the wind like the soldier’s swords. In fact, this fire is described well by a beautiful and passionate verse by Isidore of Seville: “Nothing in existence, virtually, that gets created and is not made in the fire. . . . Fire: creates and tames iron. Fire: crafts gold. Fire: incinerates stone to bind mortar and walls . . . melts frozen, binds up molten, softens hard, turns soft hard.”2 Fire is the basic element of creation.

Water, another basic element, appears in Mind Travel: waves crash against precipitous sea cliffs, fomenting the unpredictable creative and destructive forces of nature. Considered side-by-side, these eight paintings undoubtedly express a certain mythical creative principle: a linked order. Concealed in the background is a sacred ray of light that represents a yet higher knowledge. It flickers with a cyanite hue, making the large circle shape in Relics especially eye-catching. Is it Plato’s circle, signifying philosophical profundity, or Giotto’s circle, a symbol of master craftsmanship? Or is it the circle of primordial chaos, wrought by interminable ocean breezes and mountain clouds into a masterpiece of creation?3 We are led to this ultimate question: what do all of the images in the paintings imply? Perhaps it is no more than a spiritual perspective that humans once treasured:

Vast chain of being, which from God began,

Natures aethereal, human, angel, man,

Beast, bird, fish, insect! what no eye can see,

No glass can reach! from Infinite to thee,

From thee to Nothing!—On superior pow’rs

Were we to press, inferior might on ours:

Or in the full creation leave a void,

Where, one step broken, the great scale’s destroy’d;

From Nature’s chain whatever link you strike,

Tenth, or ten thousandth, breaks the chain alike.

These lines come from Alexander Pope’s famous poem “An Essay on Man.” The chain of being is the order that governs the myriad things. However, Pope also admonishes us to take precautions against the arrogance of reason: “ . . . who through vast immensity can pierce, / See worlds on worlds compose one universe, / Observe how system into system runs.” Hao Liang has evidently taken this admonition about man’s limitations to heart, for he uses his brush with moderation and restraint. Nonetheless, his restraint does not prevent him from exploring the vast expanses of the natural order. He uses Eight Views of Xiaoxiang to emphasize the duality of the human condition: the misère et grandeur de l’homme. Perhaps this explains the separate tracks of the titles and the images. Hao Liang’s tableaux contain none of the traditional motifs of homesickness, desolate landscapes, or wistful sorrow. Instead, he uses graceful forms to depict scenes of the world’s creation. His ordered extremes show the primordial circle, resplendent and magnificent, cutting open the dark night, and obliterating sorrow.

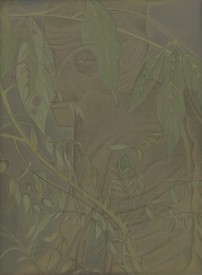

I suppose this order is a fusion of Tao Yuanming’s (365–427) “Peach Blossom” utopia and Laozi’s4 ideal of primitive society: the peach blossoms have been replaced by bamboo shoots. Hao Liang is partial to bamboo, and in previous works, he has placed it in a prominent position in the chain of being. His abstract conception of bamboo recalls Sima Guang’s (1019–1086) fanciful musings: “The bamboo on the island grows to ten meters in circumference, with the appearance of jade coins, its tips woven together, like a dwelling for the fishfolk.” Hao Liang’s special appreciation of objects like bamboo allows him to portray the chain of being as flat and equal, without grades or levels. This is the natural conclusion of his years of conceptual exploration. In the following two sections, we will retrace that exploration in time and return to his earlier works in order to see how he forged his chain of being.

II

The name for Aura, an artwork that Hao Liang completed in early in 2016 by compiling and juxtaposing several other works, originates in a quotation from Walter Benjamin: “What is aura exactly? A strange weave of space and time: the unique appearance or semblance of distance, no matter how close the object may be.” Hao Liang borrowed five classic works from the Bonnefantenmuseum to reveal the order concealed within them: The Lamentation of Christ, The Descent from the Cross, Corpus, Portrait of Evert Zoudenbalch, and Jacob’s Dream at Bethel. These works all relate to God and his servants, and the theme of Aura is revealed in the last of the paintings mentioned above.

According to chapter 28 of the book of Genesis, “[Jacob] had a dream in which he saw a stairway resting on the earth, with its top reaching to heaven, and the angels of God were ascending and descending on it. There above it stood the Lord.” In Les contemplations, a collection of poems published in the 1850s, Victor Hugo described this ladder in eloquent terms:

As on the slope of a prodigious mountain,

A vast mixture of confused noises, from the depths of the shadow,

You see the dark creation descend toward you.

The rock is further away, the animal is nearer.

Like the haughty altar, you seem!

But, say, do you think that illogical being deceives us?

The ladder you see, do you think it will break?

Do you believe, you whose senses are enlightened from above,

That the creation which, slow and by degrees

Rises to the light, . . .

Stops at the abyss of man?5

This is an alternative expression of the great chain of being: it begins with God, followed by angels, humankind, and ultimately, all the myriad things, arranged in a ladder. But this version has its problems, too:

Towards the Good do all things tend,

Many paths, but one the end,

For naught lasts unless it turns

Backwards in its course, and yearns

To that source to flow again.6(Boethius, De Consolatione Philosophiae)

The void is the enemy of God, the world of his creation also hates the void (horror vacui), and nature never skips ahead (natura non facit salturn). Similarly, with Aura, the artist does not forget the links in the chain between China and the West. In his own words, “The poetic metaphor of the ladder from Western religious paintings has entered the Chinese literati’s world. A piece of strange wood, extracted from nature, becomes a vessel of literati aesthetics, and also an indicator of worldview.” This strange wood could be seen as a version of bamboo, entering the artist’s work to fill the void, and substantiating the chain of being.

Another item in Aura: a stele rubbing by Wang Ziruo that releases the soul of the original inscription. It appears as expected through collotype technology, becoming another link in the chain.

Two further items: the portrait of a Chinese literati of ambiguous identity, side-by-side with that of a well-known Dutch clergyman (Portrait of Evert Zoudenbalch). The contrast seems to suggest that the differences between East and West nonetheless resolve to the same ends.

This multifaceted artwork concludes with a Chinese ink-wash painting, which Hao Liang describes thusly: “an arhat contemplates the reflection of the moon in a pool of water, a moment in which a false image emits a true aura”:

Those things that die and those that cannot die

Are but the splendor of the one Idea

Which in his love our Father has begotten;

For the same living Light which so streams from

The lucent Source that it is never parted

From it or from the Love which makes them Three

Through its own goodness focuses its rays

In nine existences like nine reflections,

Itself eternally remaining One.

From there to the remotest potencies

Light falls from act to act until it comes

To make now only brief contingencies.7(Dante, Paradiso)

People will discover that the greatness and sublimity of eternal strength exist because God has cast himself into such numerous mirrors. In the instant in which an aura of holy goodness bursts forth, it illuminates the limitless spiritual elements of creation and permeates downward into the various layers of potential, to the extent that the strange wood itself possesses the power of self-creation. The aura ultimately crystallizes as an organic paradox:

The one Perfect and Best Being . . . does not include itself, for it is not greater than itself; it is not included by itself, for it is not less than itself. . . . It is a term in such wise that it is not a term; it is form in such wise that it is not form; it is matter in such wise that it is not matter. . . . In its infinite duration the hour does not differ from the day, the day from the year, the year from the century, the century from the moment . . .

(Giordano Bruno, De la causa, principio, et uno)

Reproductions like collotype are not the things themselves. They are only phenomena: the moon in the water, the flowers in the mirror. Their quantity and their differences, as presented to our senses, are no more than è puro accidente, è pura figura, è pura complessione: from pure chance, from pure appearance, from pure association.

III

From Xian to Gui, a composite work from 2014, sheds light into Hao Liang’s initial conception of the chain of being. This work offers a scalae idearum (ladder of ideas) that differs from collotype reproduction.

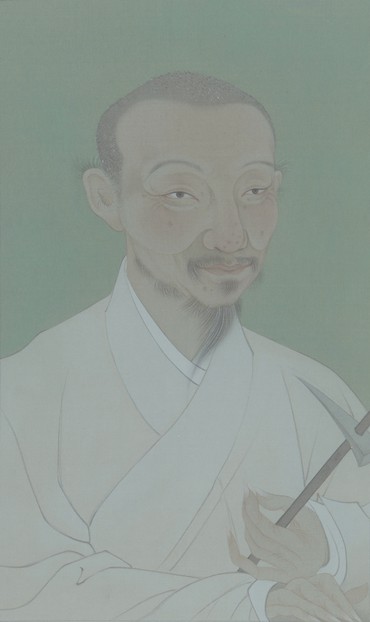

Wang Shizhen (1526–1590) was a leading thinker in sixteenth-century Chinese literary circles. He spoke up on behalf of justice and enjoyed a good reputation throughout the Southeast. He resided among the gardens, with bamboo as his perpetual companion. He once wrote a verse for his friend Wang Weiyi: “In a bamboo forest, I open my scroll and the color of the bamboo runs across it; a dawn of snow, an evening of the moon, a day of clouds, a cold wind blows toward summer. I am always assisted by bamboo.” Lucid and bright with a pen, roaming and profound in thought, Wang left for us a famous work, “Notes from a Bamboo Room.”

Hao Liang painted a portrait of this bamboo-lover standing perched on the tips of a bamboo plant, allowing the viewer to imagine Wang Shizhen transcending the boundaries of time and mortality due to the strength he draws from the lush and verdant bamboo. This supremely apt portrayal also reflects Chinese tradition in its symbolic depiction of an ascetic thinker who frees himself from the mundane world.

In addition to this portrait, From Xian to Gui also includes a series of Wang Shizhen’s letters: objects that embody the literary refinement of Chinese scholars. The custom of collecting the works of famous calligraphers began as early as the era of Wang Xizhi (321–379). Yet the content of the letters are mostly trivialities: greetings, appointments, congratulations, and the like. Although these letters are of paltry literary value, they feature the flowing beauty of Wang Shizhen’s natural and free calligraphy style. Yet the passage of time has lent more beauty to the yellowing paper, and indeed, they are the fruits and flowers of humankind:

Man’s nourishment, by gradual scale sublimed,

To vital spirits aspire, to animal.(John Milton, Paradise Lost)

Farther up on the ladder of ideas is the Daojun Emperor of the Song dynasty, who considered himself to be a Daoist immortal, a label that corresponds to a mythical Daoist paradise known as Penglai. This paradise was said to be composed of countless islands ascending into the sky. Who knows how many people since ancient times have spent sleepless nights imagining the climb from island to island toward a destination to which all the myriad things are inclined.

A painting titled Portrait of Virtuoso is another element of From Xian to Gui, but the face in the portrait seems to also be that of Wang Shizhen. Thus the Virtuoso and Wang Shizhen appear as two embodiments of the same face, perfectly reflecting another strange idea associated with the Virtuoso:

Nothing can satisfy but what confounds,

Nothing but what astonishes is true.(Edward Young, “Night Thoughts”)

Hao Liang’s formulation perfectly balances the wise man’s unique status, corresponding to Goethe’s fanciful philosophy of the “prototype”:

All links take form according to eternal laws,

and the rarest form in secret preserves the prototype.8

If Wang Shizhen ascended to the realm of the immortals through his asceticism, then the Virtuoso himself is the architect of the immortals’ palace. But the Daojun Emperor is a step higher on the ladder of ideas:

Distinguished link in being’s endless chain,

Midway from nothing to the deity.

In the work, this formerly paramount sovereign is juxtaposed with two mortise and tenon joints. The context lends these joints new meaning: are they merely the abovementioned strange wood, or do they represent the ens perfectissimum (an original and perfect object)? This question lies at the heart of our understanding of Hao Liang’s chain of being. The mortise and tenon joints could be nothing more than the handiwork of the Virtuoso. Yet their polished surfaces form a unity of material, contour, and even concept, hinting at the upward curve of the chain of being. They transform verum phisicum (physical truth) into verum metaphisicum (metaphysical truth).

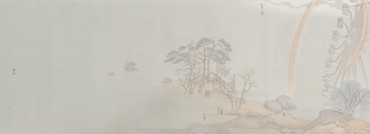

This brings us further back in time to The Virtuous Being. Begun in 2013, this work uses double entendre to make the transformation mentioned above more concrete and accessible. The Virtuous Being is a translation of 此君, characters with two meanings: “bamboo,” a physical object, and “the sage,” a spiritual person. These two concepts—physical objects and spiritual beings—comprise the mountains and rivers of the spectacular and changeable world. Within these mountains and rivers lie the awesome ruins that also appear in Hao Liang’s version of the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang. One part of the installation is the scroll of The Virtuous Being, a long and narrow landscape scroll. For the online archives, Hao Liang divided the scroll into eight sequential images to offer a more detailed expression of the beauty he discovered within relics of the past. I also strive to draw on a classical lexicon to describe these eight sections, because:

With the fine spell of words alone can save

Imagination from the sable chain

And dumb enchantment.(John Keats, The Fall of Hyperion: A Dream)

Section One: A stony ridge separates the waters, rising to arrange the space horizontally in the southern sky, an abyss beneath it; the mountains are washed by fine snow, like a beautiful woman who washes her face and begins to comb her hair.

Section Two: The waters surround the ruins, the winding fence offers scant protection; the water passes under the bridge and weaves through the white stones, the two combining to become something multifarious.

Section Three: Deep among rocky mountains, a winding waterfall ripples through ravines, flying, dashing, pouring, ice crystals of broken jade, radiating pure color, water falling through stones, without knowing where it will end up.

Section Four: Rows of crops, a ring of fine fields; huts and jade-green bamboo, sounds of chickens and people’s words on a blue-green hillside; the bird on the exposed beach, the fish sipping the waves, beyond the clouds and water.

Section Five: A series of forbidding peaks stretch steeply into the sky, upright and exposed, like outstanding calligraphy, like a chain of jade fingers; they outline the stony lakes, hollow and perforated, they inhale and exhale the wind and clouds.

Section Six: The water reflects the light, the willows make no sound, the scene is as before. Only the wooden rafts adorn the lake surface—they were not here in prior days. One day and one night, flowers bloom and wither. One autumn and one spring, things dead are reborn. In the galloping passage of time, the natural spectacle is ever-changing.

Section Seven: This is where the water flows and joins the greater river. The great wheel hangs in the air, encroaching into the boundless, bright sky. The ring of a rainbow appears, a clever illusion, to complete this rare and precious scene.

Section Eight: The dusky green swatch of river, clear of clouds and objects, profound and boundless, seems to say: the end is always imminent, with no transition between being and no longer being, returning to the void, possibly sliding into the void at any moment, it is this precipice that is creation.9

Here we seem to have arrived at the fountainhead of the chain of being, and one can’t help but think of questions of our forebears:

Where ends this mighty building? Where begin

The suburbs of creation? Where, the wall

Whose battlements look o’er into the vale

Of non-existence, nothing’s strange abode!

Say, at what point of space Jehovah dropp’d

His slacken’d line, and laid his balance by;

Weigh’d worlds and measur’d infinite, no more?

In this verse from “Night Thoughts” by the English poet Edward Young (1683–1765), the narrator seems to admit that these questions are too abstruse for simple answers. I do not think that Hao Liang’s art directly answers these questions, but there are beliefs on these subjects concealed within his paintings. His works are certainly difficult to grasp, and even cryptic, for as Eliot said: “Our civilization comprehends great variety and complexity, and this variety and complexity, playing upon a refined sensibility, must produce various and complex results. The poet must become more and more comprehensive, more allusive, more indirect, in order to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into his meaning” (“The Metaphysical Poets”). These challenges faced by the poet are also faced by the philosophically inclined painter. Hao Liang will not directly raise the questions posed by “Night Thoughts,” but variations of these questions are always present, because we fear losing the philosophical excitement of the past, we fear being cut off from the ancient world, and most of all, we fear being unable to find that remote fountainhead. We collect ancient relics; when we happen to find one or two, we are filled with pleasure. We adoringly treasure their elegance, dwell on their contributions to the clarity of the historical record, and seize the opportunity to appeal to people’s interest in the past. But these collections are fragile. A bit of warfare or calamity could easily extinguish them. We hope that they will become eternal objects, but we invariably prove that eternal is impossible, that eternity is void. Indeed, the true message of the history of our universe is:

The scene is extinguished

Yet the feelings remain

This notion lies behind the supplementary component of The Virtuous Being, which is called Research for the Virtuous Being. Bringing our attention to his research process, the artist displays a series of historical objects in order to provide support for the philosophical inferences underlying his artwork. In this way, he ultimately shows that the fragmented stones scattered among the mountains and ruins are in fact the greater work of art. This unexpected addendum is profound in its significance:

Nevertheless, no one among the ancients who learned the Way gained access to it through vacuity and emptiness. Wheelwright Bian fashioned wheels, and the hunchback caught cicadas. If it suffices to release a man’s ingenuity and wisdom, no thing is too lowly. If Sicong succeeds in attaining the Way the zither and calligraphy will have contributed to his achievement, and poetry will have played even a larger part. Once Sicong is able like a bright mirror or clear pond to admit ten thousand images into the one, then his calligraphy and poetry will be even more extraordinary. I will look to these forms of expression by him as indicators of the depth of his attainment of the Way.

These lines from Su Dongpo’s “Narrative of Sending the Qiantang Monk Sicong Back to Lonely Mountain” show that although Su was proficient in Buddhist scripture, he did not delve into “the void.” He followed the model of ancient civilization, recalling the stories of Zhuangzi, in which artisans attain spiritual transcendence and freedom by carrying out their work with great skill and intuition. When he cites the examples of Wheelwright Bian and the Hunchback, he is undoubtedly also thinking of the painter from another chapter of Zhuangzi who “casually and without hurrying . . . half-naked, with his shirt off.”10 These characters stirred the spiritual minds of artists of subsequent generations. In a certain sense, many of Hao Liang’s works are homages to these ancient characters. He also tirelessly studies the classics and persistently draws on the forms of classical calligraphy and painting. He even appropriates ancient material to create expressions akin to those of Magritte, satisfying the taste of contemporary audiences for philosophically abstruse art, and more: his explorations of the world of antiquity have led him to perceive the symmetry between the order of the spiritual realm and the grand solemnity of the cosmos. It is within this solemnity that he locates his artistic inspiration.

1Chinese Zen Buddhist monk and painter who lived in the thirteenth century, around the end of the Southern Song dynasty.

2English translation excerpted from John Henderson, The Medieval World of Isidore of Seville: Truth from Words (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 201. Original: Nihil est enim paene quod non igne non efficiatur . . . igne ferrum gignitur ac domatur, igne aurum perficitur, igne cremato lapide caementa et parietes ligantur . . . stricta soluit, soluta restringit, dura mollit, mollia dura reddit.

3The imagery here is a reference to portrayals of the moon in the Song-Yuan painting tradition. The circle of primordial chaos (浑沦之圆) specifically refers to Zhu Derun’s Hunlun tu. (Trans.)

4The founder of philosophical Taoism who lived during the Warring States period of the fifth or fourth century BCE. (Trans.)

5Comme sur le versant d’un mont prodigieux,

Vaste mêlée aux bruits confus, du fond de l’ombre,

Tu vois monter à toi la création sombre.

Le rocher est plus loin, l’animal est plus près.

Comme le faîte altier et vivant, tu parais!

Mais, dis, crois-tu que l’être illogique nous trompe?

L’échelle que tu vois, crois-tu qu’elle se rompe?

Crois-tu, toi dont les sens d’en haut sont éclairés,

Que la création qui, lente et par degrès

S’élève à la lumière, . . .

S’arrête sur l’abîme à l’homme?

6Hic est cunctis communis amor,

Repetuntque boni fine teneri,

Quia non aliter durare queant

Nisi converso rursus amore

Refluant causae, quae dedit esse;

7Translation excerpted from http://www.italianstudies.org/comedy/Paradiso13.htm.

Original:

Ciò che non more e ciò che può morire

non è se non splendor di quella idea

che partorisce, amando, il nostro Sire;

ché quella viva luce che sì mea

dal suo lucente, che non si disuna

da lui nda l’amor ch’a lor s’intrea,

per sua bontate il suo raggiare aduna,

quasi specchiato, in nove sussistenze,

etternalmente rimanendosi una.

Quindi discende a l’ultime potenze

giù d’atto in atto, tanto divenendo,

che più non fa che brevi contingenze.

8Alle Glieder bilden sich aus nach ew’gen Gesetzen,

Und die seltenste Form bewahrt im geheimen das Urbild.

9La fin toujours imminente, aucune transition entre être et ne plus être, la rentrée au creuset, le glissement possible à toute minute, c’est ce precipice—là qui est la création.

10Victor Mair, Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000).

Text translated from the Chinese by Daniel Nieh; originally published in Hao Liang: The Virtuous Being (Maastricht, Netherlands: Bonnefantenmuseum, 2018)