Joey Frank is an artist and author. He is deeply interested in astrology and parallax vision. Frank lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Sam Lipsyte is the author of five novels and two short-story collections, including The Ask, Hark, and the forthcoming No One Left to Come Looking for You. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, n+1, Noon, Open City, The Quarterly, Best American Short Stories, and elsewhere. He lives in New York City and teaches at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. Photo: Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

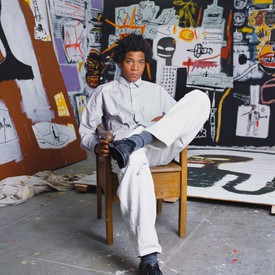

Jordan Wolfson was born in New York in 1980 and lives and works in Los Angeles. Filtering the languages of online and broadcast media through digital and mechanical technologies, and employing an array of invented characters, he crafts enigmatic narratives that explore uncomfortable social and existential topics. Photo: Collier Schorr

Here’s a coincidence: I was dictating this brief introductory text, the text you’re reading, into my phone, a robotic intelligence that translates speech to text. The software understood Sam Lipsyte’s name as “Sam Website.” When Emma Cline first mentioned this project, of pairing Jordan Wolfson and Sam Lipsyte together for her Picture Books series, we were in a car that Jordan was driving, and at a red light, with divided attention, he turned to Emma and said, “Wait, the guy’s name is Sam Website?”

Anyway, when I moved to New York, around 2005, Sam’s first collection of short stories, Venus Drive, was in the collections of all aspiring writers. Since then, a Guggenheim Fellowship and many more books later (my favorite being The Ask), Sam Lipsyte is rightly known as a prose stylist of generational talent. Sam writes stories about the state of the everyman—smart guys but not always smarter than the reader, protagonists like Jason in Friend of the Pod, a cash-strapped Gen X-er who finds himself entangled with egomaniacs. Meanwhile, I’ve known Jordan for many years. Actually, I remember, in the same friend’s apartment where I first saw one of Lipsyte’s books, showing Jordan’s The Crisis (2004), a four-minute video of the artist talking autobiographically, in a cathedral, about his love of art. In retrospect, this work functions as a sort of short story in Jordan’s catalogue. Wolfson is a master of provocation and of channeling feelings in a way that makes them both alien and manageable. He’s particularly potent on issues of anger and dissociation from anger. Emma first asked me to do an astrological reading of these two men, but I can just say that all three of us are air signs and we talked on Sam’s birthday, which happened also to be the summer equinox.

—Joey Frank

Joey FrankWhen Emma asked me to conduct this interview, my first thought was that the ego in your work, Sam, is so different from the ego in Jordan’s work. But I just read your essay “Ghosting the Machine: Humans, Robots, and the New Sexual Frontier,” for Harper’s, which in my mind very much aligns with some of Jordan’s work, especially his animatronic work Female Figure [2014].

Sam LipsyteI think there are lines to be drawn between them.

JFIn Sam’s essay he talks about the future of sex with technology. But Jordan, I want to start by asking you something we’ve never discussed in the course of our friendship: Did you ever develop sexual feelings for your artwork?

Jordan WolfsonNo, for me it was always about sculpture and the viewer. I was actually afraid of it—the artwork—because it was so uncanny in person, so lifelike. I remember standing alone with it in a warehouse in Burbank late one weeknight and its eyes darted up at me. I ran out to my car as fast as I could.

SLThis piece I just wrote for Harper’s was about a trip to the Erotic Heritage Museum in Las Vegas, where I attended a presentation on the future of sex, pornography, and erotic technologies. One of the more interesting things I took away from this assignment was that these tech-sex creators can’t seem to imagine building a doll that doesn’t look like a very conventional idea of what’s sexually attractive or what’s erotic. They might imagine themselves to be transgressing certain boundaries, but there’s something ultimately conservative about the approach. But I relate to that fear you’re mentioning, Jordan—it’s more about the fear of a machine and maintaining a comforting adjacency to the familiar.

JWYeah, Walter Benjamin said this interesting thing, that human beings are terrified of holding wild animals—they need to hold wild animals with gloves—because if they were to hold the body of a deer in their hands, they would feel the animal’s heart pumping and it would remind them of their own consciousness. We have this inability to imagine that wild animals are conscious in the same way we are conscious. That this could occur with a robot or a machine takes this to another level.

JFThat’s a great reference, because, Sam, in your essay for Harper’s you write about meeting, if that’s the right word, this sex doll and how you had to wear gloves to touch her, right?

SLYes, but not so much to avoid acknowledging her consciousness but because—and I don’t know if this was just this particular model or this particular doll—the skin was so delicate that the oils in human skin would destroy it and everyone had to handle her with gloves. She was starting to shred just sitting in a chair for two years with no one touching her. It was strange. I’d have to say that this model was still taking the hike up to the ridge before reaching the uncanny valley.

JFYour article got me thinking about the relationship between the artist and what’s being made, like a Frankenstein or an automaton. Does intimacy or identification factor into that relationship? Or is it always the big-“O” Other?

JWI don’t think intellectually when I’m making art. I would find that disruptive. I don’t think conceptually, either. It’s nice to look back conceptually—or intellectually—on these things, but for me, it’s about feeling and it’s about form. Ultimately, I’m trying to generate some kind of feeling from myself when I’m looking at an artwork. And often that feeling is a feeling of activated confusion brought about when you have a number of opposite things colliding that aren’t supposed to be together, for example.

SLThat’s how I work too. The worst thing is to have an idea. The whole point of making it is to find out what it is. And then you look back and say, Oh, I still don’t even know what it is. I still need other people to tell me pretty much what it is. I’ve often thought Gilbert Sorrentino, a brilliant writer whose book Lunar Follies I think both of you would get a kick out of, said it well: “No artist writes in order to objectify an ‘idea’ already formed. It is the poem or novel or story that quite precisely tells him what he didn’t know he knew: he knows, that is, only in terms of his writing. This is, of course, simply another way of saying that literary composition is not the placing of a held idea into a waiting form. The writer wants to be told; the telling occurs in the act itself. And when the act is completed, its product is, in truth, but a by-product.” That by-product is what other people get from the artist going through the process of that telling.

JWWhen I selected the image for Friend of the Pod, I didn’t even think about it, I just knew that I wanted to do this image of Sam Kinison screaming.

JFWhy do you think, of all things, this was what came to you?

JWAs I was reading Sam’s story, I would write things down. Again, really, I don’t know what to call it other than intuition. I had some other ideas written down too, but Sam Kinison stuck with me. I also had this image of two male lovers from a celebration in Brazil; I thought that would be a nice picture for the story.

JFIt’s interesting—Sam, you have a relationship with stand-up comedy, right? I know you and Marc Maron are good friends.

SLYeah, he’s one of my best friends. What’s interesting is, he has a lot of stories about when he was first starting out and he sort of fell under the tutelage of Kinison, who really brought him to the edge of insanity. So there’s a nice circularity to this Kinison vision that Jordan had. I remember watching Kinison as a kid. That scream was extraordinary. It cut through the malaise, the din. He’s been a preacher, I think. And a lot of podcasters are secular preachers of one kind or another.

JFRight, and we’re speaking about Marc, who has perfected the podcast as a genre, and your story for Picture Books is about a podcaster, Ted Goldworthy, who hires the protagonist, Jason. Ted’s a great archetypical podcaster, right? He’s just this old guy in his basement in New Jersey with this huge confidence; he thinks he knows better than Jason on everything . . . and, well, maybe he does.

SLHe thinks he knows better than everyone—

JFExactly, it feels really very current. We went through the Trump era and now Biden is in the White House—it’s this stream of old men.

SLThe gerontocracy, yes. Absolutely no one is going to listen to this podcast, ever, but he feels he has all these important things to say and he’s got some money, so he’s going to pay someone to help him produce it. These characteristics aren’t in any way unheard of in the contemporary world.

Also, with podcasting in general we’re in this age where stand-up comedy, as a form, has become an aspect of so many people’s lives—everyone’s monologuing. It’s not funny anymore, though—just a slew of people giving their political opinions and their hot takes on cultural events, never interacting. That’s the podcast world we’re in. And with Jason, too, I was interested in developing this character who was hapless, who’s been bouncing around in new-media worlds for years, from gig to gig, never quite landing anywhere.

JWThat’s how I feel about my life [laughs]. I’ve been bouncing around the art world doing this and that.

SLI think you’re doing a little better than the guy in the story [laughter]. But, also, yes, that’s part of it—he’s today’s everyman. This is the life of a lot of people I know, including me on some level, although I’ve been more tied to an institution for a long time. But also, part of the story—especially where it ends—was thinking about how we’re all the heroes and narrators of our own stories and sometimes we don’t realize how much we’re just doomed bit-players in someone else’s narrative. Or NPCs, as the kids say. It was rewarding to build Jason’s interiority, this grand, complex thing, and then have it completely snuffed out. In a manner of speaking.

JFSam, after this novella is released in the Picture Books series, I understand you have another book coming out that’s set in 1993. That feels like a year people keep returning to as emblematic of something in the worlds of culture. Jordan, do you remember we went to that exhibition at the New Museum, NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star [2013]? It had Paul McCarthy’s Cultural Gothic [1992] and Derek Jarman’s Blue [1993], do you remember?

JWI don’t remember that, but when I think about 1993, I think there was really good art being made. And there was also incredible music. On the other hand, 1993 is this point when awful music, which we’re still bearing the repercussions from, emerged in this big way. I’ve been listening to that track “Forever Young” by Alphaville from the ’80s over and over again. I’m somehow obsessed with it. It starts really good—it’s actually beautifully written—and then it spirals and the lyrics seem less and less potent toward the end.

SLThat’s a metaphor for 1993.

JWAnd then, 1993, I think of the Dave Matthews Band and Counting Crows’ “Mr. Jones.”

SLYes, but all of that was happening at the same time as good music.

JWBut the great bands like the Pixies couldn’t survive, ultimately, with “Mr. Jones” taking over the radio, could they?

SLNo. They made some money later doing reunion tours, but they went through some bleak times, I’d have to think. Don DeLillo wrote that the Kennedy assassination broke the back of the American Century, but maybe it was really “Mr. Jones” that did that.

JFBut Jordan, does the art from that time inform your practice? Like McCarthy, Sean Landers, Cady Noland, Felix Gonzalez-Torres . . .

JWOf course. My work really comes from postmodernism, and the 1990s are quintessentially postmodern. Generally there was a certain kind of meanness in these artists’ work that I appreciated, that kind of angry, mean assault—so much was at this aggressive frequency.

SLI was telling a student recently, You’ve got to be meaner.

JWAbsolutely, you’ve got to be meaner. When I’m putting things together, or working on choreography or editing, I try to get the parts together in intuitive ways that fit and then abruptly don’t fit. I don’t actually think about it so much, it’s more of a feeling and “feeling out,” but the result often is that the attitude is hard, kind of mean, then at a certain point it becomes something else and the total form itself tells something.

JFSam, why did you choose 1993 for this new book?

SLIt takes place in the East Village in 1993, and ostensibly it’s about a band, but in a more general sense it’s a quest story. It begins with the bassist waking up and realizing that his lead singer has stolen his bass to sell it for drugs and he must go on a quest across the city to find his instrument and his front man. A variety of obstacles arise . . . a couple of murders and political intrigue and the implosion of a scene. As Jordan was getting at, the year was both a pinnacle and the beginning of the end. And even Donald Trump makes an appearance.

It takes place over three days in the winter, right before the huge blizzard that happened that year.

JFThe funniest, most Jordan sentence in Sam’s piece for Harper’s was this part where he was talking about the robot, and he doesn’t know whether, as a journalist, he’s supposed to have sex with it for professional due diligence. And it’s clear that it’s a museum, so the answer is no. And Sam writes, “Well, yeah, it’s not like you can fuck Michelangelo’s David” [laughs]. I know, Jordan, that Michelangelo’s David is one of those pieces kind of like “Forever Young” for you, in that it drives you crazy.

JWI’ve been to see that work three times. Each time, I spent about forty-five minutes with at least 100 or 250 other people looking at this sculpture. For forty-five minutes, just staring at it. And I’ve never had an experience like that—in a lot of ways, it was like a collective erotic experience. The body is so beautiful, the proportions are so uncanny and weird, that you just can’t stop looking at it. It’s a masterpiece from . . . definitely eight out of ten angles. But there are like two bad angles to look at the sculpture.

JFI just like the idea that with the robots and creating a love robot, there’s this line between what is a sculpture and what is a tool for sex and what is an intimate partner.

JWYeah, Joey, there is a difference. You know, being engaged sexually, with yourself or with a partner, is a different mode from that mode in which one looks at and with art. At least for me, those things are separate. Sam, can you speak to that at all? Because Joey, you keep on going back as if there’s a fetish hidden inside both Sam and me, and potentially there’s not, we’re just human beings who can switch these modes—you know, Sam is doing his writing mode and I’m doing my visual-arts mode. And within those modes, we hope, there’s a space of brutal objectivity that doesn’t exist in our normal lives.

SLI agree with that. Form is essential there. We’re looking to contain the swirl of these feelings and these impulses and visions. That’s the whole point.

JWThe artwork’s no longer an artwork if you have sex with it.

SLYeah, I mean, I believe that you can have an erotic experience in the vicinity of an artwork, but if you’re having sex directly with it, then it’s probably something else.