Eleonora Di Erasmo is an art historian and curator. Since 2008 she has been working for the Cy Twombly Foundation, focusing in particular on the catalogues raisonnés of Twombly’s drawings (vols. 1–8) and sculpture (vol. 2). She runs the Foundation’s office in Rome and together with Nicola Del Roscio she recently curated the project Un/veiled: Cy Twombly, Music, Inspirations.

It must be visible or invisible,

Invisible or visible or both:

A seeing and unseeing in the eye.

—Wallace Stevens, Notes toward a Supreme Fiction, 1942

In Notes toward a Supreme Fiction, the poet Wallace Stevens asks us to look at the sun with eyes that don’t know it, that are unfamiliar with its form, as if they were seeing it for the first time, perceiving its primordial idea, the sun as it was before we existed:

How clean the sun when seen in its idea.

Washed in the remotest cleanliness of a heaven

That has expelled us and our images . . .

. . . There was a project for the sun and is.

There is a project for the sun. The sun

Must bear no name, gold flourisher, but be

In the difficulty of what it is to be.1

The difficulty of being, the awareness of one’s own imperfection in the face of the perfection of nature, sparks in the poet the need to return the sun to its “first idea,” the desire to complete reality in order to reunite it with the reason of the world, to grasp a meaning in it that irremediably escapes the gaze of imperfect beings and is only ever revealed in brief moments, in the form of fleeting epiphanies.2

In a series of drawings made in 1990, Twombly noted the words “Delight lies in flawed words and stubborn sound,” a slightly modified quotation of the ending of Stevens’s “The Poems of Our Climate” (1938).3 The full passage runs,

Note that, in this bitterness, delight,

Since the imperfect is so hot in us,

Lies in flawed words and stubborn sounds.4

The creative process stems from the incessant state of need. The artist feeds on reality, investigating and probing it in all its details, conveying it naked.

Overexposure becomes a filter, a veil that is needed in order to be able to focus the gaze better and perceive what is closest to us, but that we normally struggle to recognize in its original essence. The truth that would otherwise remain invisible to the eyes.

The lens becomes an extension of the eye, “a subsidiary organ of sight, of memory.’5 Thus the use of mythology, the references to classical culture and modern literature, become a means of decoding the world and understanding human emotions, beauty and its contradiction, the universal relationship between things that governs the incessant forward movement of our existence. The coat of white paint with which Twombly covered his sculptures, assemblages of objects found by chance, transfigures them, and in this process of abstraction the artist strips them of their names, of their human trappings, bringing them back to their essence, to what preceded us:

There was a muddy center before we breathed.

There was a myth before the myth began,

Venerable and articulate and complete.6

In their turn, the eyes of the artists invited to take part in Un/veiled, and their music inspired by and dedicated to Twombly’s work, become further filters, new points of view from which to observe the artist’s creations. On the one hand Eraldo Bernocchi, composer of Like a Fire that Consumes All before It, soundtrack of the documentary film Cy Dear (2018), uses the reverberating sounds of his electric guitar to take us on a journey through the flow of memory.7 Time is deprived of its chronological progress, at times dilating, at others turning back on itself, in a continual alternation of instants, of memories of life lived, of meetings, of emotions. On the other hand, with To Neptune, Ruler of the Seas Profound (2019), Isabella Summers writes a personal story about some of Twombly’s most celebrated works, composing in fragmentary recordings and quotations of poems, just as Twombly used to notate and cite fragments from favorite poems in his paintings.

In the same way in which Twombly assembled the most disparate objects to create his sculptures, Pierre Henry, a pioneer of musique concrète and electronic music, manipulated and remodeled audio material—“sound objects”—to produce his compositions. In 1953, as Nicola Del Roscio has written, Twombly was struck by a concert of Henry’s Le Voile d’Orphée (1953) that he heard on the radio, and years later he drew inspiration from it for the paintings Treatise on the Veil (1968) and Treatise on the Veil (Second Version) (1970).8

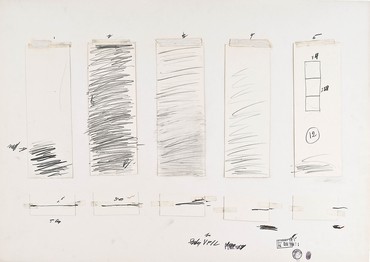

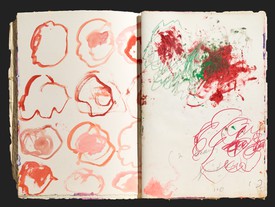

Le Voile d’Orphée opens with the manipulated sound of a piece of cloth being ripped, a sound that serves to symbolize the dramatic death of Orpheus, whose body is torn to pieces by bacchants. The sound expands as if suspended in a time without end, which Twombly conveys in his Treatise on the Veil paintings through a series of continuous lines, parts of broken lines, and numerical inscriptions. Traced in wax crayon on a dark ground, the lines run along the lower part of the two paintings, as if to measure the space of the canvas and beat out the rhythm of an inner tempo, calling to mind the scores of postwar avant-garde music.

That same tempo dilates in the echoing sounds produced by the piano of Harold Budd. He in turn took inspiration from the Treatise on the Veil works to compose his Veil of Orpheus (Cy Twombly’s) (2012), whose cadenced progress, made up of poetic pauses and suspensions, almost seems to be reminding us of the phrase Twombly used to describe his Treatise on the Veil: “a time line without time.”9

Republished from the introduction for the Un/veiled catalogue (translated by Christopher Huw Evans).

1Wallace Stevens, Notes toward a Supreme Fiction, 1942. Available online at https://genius.com/Wallace-stevens-notes-toward-a-supreme-fiction-annotated (accessed July 12, 2022).

2Ibid.

3See Nicola Del Roscio, ed., Cy Twombly: Drawings. Cat. Rais. Vol. 8 1990–2011 (Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 2017), pp. 68–73.

4Stevens, “The Poems of Our Climate,” 1938. Available online at http://thepoemoftheweek.blogspot.com/2006/06/poem-of-week-6192006-poems-of-our.html (accessed July 12, 2022).

5Paolo Maurensig, L’ombra e la meridiana (Milan: Arnoldo Mondadori, 1998), p. 9.

6Stevens, Notes toward a Supreme Fiction.

7Andrea Bettinetti, Cy Dear, produced by Good Day Films, Milan, 2018.

8See Del Roscio, ed., Cy Twombly: Drawings. Cat. Rais. Vol. 5 1970–1971 (Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 2015), p. 9.

9Twombly, quoted in Isabelle Dervaux, “Interstices of Time: Cy Twombly’s Treatise on the Veil,” in Michelle White, Dervaux, and Sarah Rothenberg, Cy Twombly: Treatise on the Veil 1970 (Houston: The Menil Collection, 2019), p. 14.

![Cy Twombly, Treatise on the Veil (Second Version), 1970 [Rome], oil-based house paint and wax crayon on canvas, 118 ⅛ × 393 ⅝ inches (300 × 999.8 cm), The Menil Collection, Houston. Artwork © Cy Twombly Foundation](https://gagosian.com/media/images/quarterly/essay-cy-twombly-imperfect-paradise/Q6fgJVbFdSgX_585x1170.jpg)