Artist to Artist: Rachel Feinstein and Ewa Juszkiewicz

On the occasion of Frieze New York 2021, the two artists discuss remixing conventions, the allure of Rococo, and the importance of research and history within their respective practices.

November 1, 2023

Writer and art historian Jennifer Higgie met with Ewa Juszkiewicz to learn more about the painter’s process, her varied inspirations, and her views on the social and emotional roles of art.

Ewa Juszkiewicz in her studio, Warsaw, 2023. Photo: courtesy the artist

Ewa Juszkiewicz in her studio, Warsaw, 2023. Photo: courtesy the artist

Jennifer HiggieI thought we could start at the beginning: What was your first experience of art?

Ewa JuszkiewiczI remember when I was a teenager, I was fascinated by Early Netherlandish painting, the work of Jan van Eyck, Robert Campin, or Hieronymus Bosch. Their paintings captivated me with their incredible technique and precision. In the National Museum in Gdańsk, my hometown, there is an amazing painting The Last Judgment by Hans Memling. I still remember how impressed I was with this triptych, its extraordinary richness and brilliance of colors.

JHWas anyone in your family artistic?

EJNo, but we had a lot of art books at home, which shaped my taste and sensitivity to art. The first artist who made a strong impression on me when I was a few years old was Picasso. I remember being enchanted by his different periods and his approach to portraiture. I’m convinced that it was Picasso’s work that initiated my fascination with painting.

JHAnd of course Picasso often referenced masks.

EJYes, I’m sure it’s all connected!

JHWhere did you spend your childhood?

EJIn Gdańsk, in northern Poland. It’s a city with a thousand-year history, so on a daily basis I was surrounded by old architecture, monuments, and historic churches full of antique paintings. In a natural way, in my childhood the art of the past was much closer to me than contemporary art.

JHWhen did you know you wanted to be an artist?

EJI feel I was born to be a painter, but I knew clearly from the age of eight.

JHHow did your artistic language evolve while at art school?

EJAt that time my artistic language was still in formation. My works back then were much more expressive. I experimented a lot, explored different media and techniques. But from my perspective today, I think my style developed mainly by studying old paintings—through visiting museums and direct contact with art.

JHAt what point did you become interested in a more feminist reading of pre-Modern paintings?

EJIt was around 2011, when I was researching eighteenth- and nineteenth-century paintings. While I was fascinated by the amazing artistry of portraits from that period—their aura, richness, and harmony—I realized that most of them tended to represent women in a very stereotypical, highly idealized way, according to a male ideal of beauty. Their poses and gestures are often repeated and their facial expressions are uniform. So I felt the need to engage in a dialogue with it. By disrupting historical portrayals of women, I want to break the hold of traditional ways of seeing and give these images new content and meaning. My goal is to disturb existing aesthetic conventions and liberate what is hidden behind them: individuality, expression, vitality.

Ewa Juszkiewicz, The Hunting (after Marie-Denise Villers), 2023, oil on canvas, 70 ⅞ × 55 ⅛ inches (180 × 140 cm)

JHWhen did you first become aware of artists such as the French eighteenth-century portrait painter Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun?

EJI think I first saw her work in the Louvre, several years ago.

JHWhat about it attracts you?

EJIt’s a mix of the brilliance of her paintings and her extraordinary life. She made her way in a male-dominated art world, became Marie Antoinette’s favorite painter, found her own style while employing the conventions of the day, and had great career success, even though she had to flee the French Revolution. I love the quality of her brushstrokes and her deep sensitivity to color.

JHThe women she depicted were very fashionable, obviously, but she represents them as strong, empowered.

EJTrue, some seem strong and confident, others, fragile and delicate. She’s also brilliant at painting very intimate scenes. Her self-portraits with her daughter, for example, transcend cliché. But most of her portraits are highly idealized, which makes them an endless source of inspiration for me.

JHTell me more of your thoughts on the relevance of the art of the past to the art of the present. Do you see what you’re doing as a way of reanimating history?

EJAbsolutely. My work dialogues with history—I reference classical paintings and traditional ways of presenting. By appropriating and processing images from the past, I build new meanings and create my own stories. Such dialogue, in my opinion, brings history to life. It keeps painting alive. While I work from reproductions, transforming certain sections of the painting very freely, I also try to preserve the style and character of the painting I’m referring to, faithfully following the original brushstrokes. This is an important part of my process. For me, it is a symbolic way to find a connection and closeness with a painter from the past. A form of establishing bonds and evoking presence.

JHIs each of your paintings based on an actual painting?

EJMost of them are based on historical artworks, but I do invent characters in some. Sometimes I use my own body as a model.

JHDo you regard your pictures as a form of self-portraiture?

EJNo, not really. When I reference my body, I focus on clichés and conventions of portraiture and rework them. When I pose, it’s an echo of the way women were presented in the past. In other words, it’s not self-expression; I’m just a tool.

JHAlthough your work often references historic painting, there’s something very idiosyncratic about it, too. Could you talk about the role of intuition in your work?

EJIt plays a crucial role. My choices and decisions are guided by my emotions, dreams, and irrational feelings. When a vision for a painting appears, new forms and shapes swirl and grow in my imagination. It happens automatically. I allow my ideas to develop freely and naturally.

JHIn terms of making your paintings, what’s your process?

EJIt is complex and layered. The first stage is research. I look for historical portraits that embody convention, but I also search for intriguing details that catch my attention. It could be interestingly pinned-up locks of hair, a piece of clothing, sophisticated drapery, or the gesture of the sitter. Once I have a vision of how I am going to transform the selected portrait, I build masks and objects that will serve as a reference or a base for my painting. I collect varied wigs, textiles, old jewelry, and plants, which I use in building my sculptures. I then either paint the objects from life or take photographs to work from.

Ewa Juszkiewicz, In a Shady Valley, Near a Running Water (after François Gérard), 2023, oil on canvas, 106 ¼ × 63 inches (270 × 160 cm)

JHYou use quite a traditional painting technique. Could you walk us through it?

EJMy process is time consuming. I build up numerous layers of oil paint and glazes. I pay attention to the details, and sometimes I spend weeks finishing just a section. Recently I have begun sourcing canvas from a traditional Belgian manufacturer. Interestingly, René Magritte is said to have worked on their canvas as well!

JHThat’s a great find!

EJYes, it’s a lucky story.

JHUp close, the surfaces of your paintings are more organic and gestural than you might assume when you see them from a distance.

EJThe diversity of textures in a painting has always been important to me. The oil technique is incredibly attractive precisely because it allows such opportunities to play with the paint, to experiment with textures and opacity levels. I like to try various effects and different combinations. Oil paint is full of infinite possibilities, and the effect is often unpredictable. As a result, the work’s surface becomes organic and alive. It changes depending on which angle it’s viewed from. For me, this is the essence of painting.

JHYour paintings are full of literary references. What impact did books and writing have on the development of your work?

EJA great influence! For instance, Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth (1990), about the oppression of the myth of beauty, was a major inspiration, as were Hans Belting’s Face and Mask (2013), which examines the history of the human face and masks, and Umberto Eco’s Ugliness: A Cultural History (2007). Of course, Linda Nochlin’s essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (1971) has been important to me in terms of its analysis of the structures of gender exclusion. Many years ago I was moved by David Sylvester’s interviews with Francis Bacon in The Brutality of Fact (1987). I like to go back to their conversations and Bacon’s thoughts.

JHWhat kinds of thoughts?

EJThoughts about his process and his obsessions. The role and importance of chance and accident in his painting, and his reflections on painting based on photographs and reproductions. Bacon was completely honest and free in his approach to picture making. He took history and made it his own, for example in his series of paintings based on Diego Velázquez’s portraits of Pope Innocent X.

JHYou’ve also mentioned the impact of Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935) on your thinking.

EJIt’s such an important text for the questions it raises concerning originality and repetition, aura and authenticity, creation and imitation. All of this is relevant to my work in terms of its relationship to reproduction—which Benjamin assumes to be a creation devoid of an aura.

JHIt’s very interesting thinking about Benjamin in terms of your work. You’re reproducing something, but you’re also making it original and giving it a twenty-first-century aura.

EJI have always believed that the most interesting concepts arise from a combination of traditional elements and modern ideas. As we know, the remix is nothing new in art; appropriation has been a common strategy since the beginning of the twentieth century. Also, the history of painting is one of borrowing from, and processing, the achievements of the artists of the past. I follow the conventions of historical painting in some aspects, through classical composition and traditional painting technique, but I change and replace things with my own ideas.

JHThere’s a real focus on fashion in your paintings. It seems to both entrap the women you depict and also lend them a kind of expressive freedom. What do you see as its role?

EJFashion is fascinating because it reflects the era we’re living in. It can be a cure for reality. Our fears and our longings can be reflected in the clothes we wear, too. I grew up in the early 1990s, right after Communism ended in Poland. At that time, everything on the Polish streets was drab, there was no color, everyone was wearing gray. It was tough. The fashions I saw in magazines were such a window to other worlds, full of color and expression. So, back then, fashion meant freedom to me. In terms of the fashions depicted in old paintings, I love how visually rich they are—all the ornaments, geometries, jewelry, gigantic hairstyles. But on the other hand, crinoline and corsets restricted women and determined how they should move, sit, talk. So, for me, historic fashion also symbolizes oppression and discipline.

JHWhat contemporary designers do you like?

EJI love designers who break with convention about how women should look and what shape their bodies should be—the ones who treat the female body in a sculptural way, like Rei Kawakubo, Iris van Herpen, Alexander McQueen, Viktor&Rolf, and Martin Margiela.

JHYou often employ humor, as for example in the wonderfully absurd situations you depict where a woman’s face is entirely covered by the same fabric as the dress she’s wearing.

EJUsing humor and the grotesque and balancing on the edge of absurdity allow me to protest stereotypical perceptions of femininity. I wish to draw attention to the insufficient presence of women in traditional versions of history, including the history of art. Their contributions to culture or science have been marginalized and undervalued for centuries. So many women artists have been lost to history. In some of my paintings, I cover female portraits with plants, fruits, and other elements that were part of Dutch Golden Age still lifes. In this way, I want to highlight the reality of female artists in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In those days, women had limited access to artistic education, to career success as artists (or anything else). For example, they couldn’t openly study anatomy from the nude model, and hence couldn’t receive adequate training. These limitations induced them to paint still lifes. They often became specialists in painting flowers and other botanical compositions.

Ewa Juszkiewicz, Girl With a Fan (after Johann Heinrich Tischbein the Elder), 2023, oil on canvas, 39 ⅜ × 31 ½ inches (100 × 80 cm)

JHI read that you were very influenced by Cindy Sherman’s History Portraits [1988–90].

EJThat’s true! All her work is incredibly revealing to me, from her early 1970s photographs to her most recent material. The way she raises issues of identity, and the image and role of women, is groundbreaking from the point of view of art history and had a strong influence on my own explorations.

JHAlong with Vigée Le Brun, who else is a lodestar from the past?

EJOf the painters whose work I refer to directly, I could mention Louis-Léopold Boilly, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, François Gérard, Joseph Wright, Joseph Karl Stieler, and Thomas Sully. But there are many, many more, of course. As for the twentieth-century artists who inspire me, I have recently been exploring and analyzing the work of the British Argentinean Surrealist artist Eileen Agar, which seems, in some ways, very close to mine.

JHWhat about it do you like?

EJIts poetic nature and use of humor. Agar’s original combinations and solutions, and her brilliant and unusual look at femininity, are fresh and inspiring to me.

JHWhat is it about Surrealism that inspires you?

EJIts focus on human emotions and desires. The way it reaches into the subconscious, drawing from the world of dreams and nature. That there is no place for rationality and convention in it—it’s too full of contradictions and strangeness.

JHAre there Polish Surrealists you admire?

EJI appreciate the work of the sculptor Alina Szapocznikow and the paintings of Erna Rosenstein, but, along with Leonor Fini, my main Surrealist influences are Leonora Carrington and Louise Bourgeois. The work of René Magritte, Meret Oppenheim, and Max Ernst also fascinates me.

JHDo you have a favorite museum?

EJThere are so many! One is the Met in New York. I value their collection of ancient art and European paintings. Their contemporary shows are great, too. Rei Kawakubo / Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between (2017) was a highlight. In Madrid, I love the Prado for its huge collection of Francisco Goya and Hieronymus Bosch paintings, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum’s fifteenth-century Italian collection. In Berlin, I have a favorite painting in the Gemäldegalerie: Portrait of a Young Girl (1465–70) by Petrus Christus. It’s a fantastic painting, and I’m always so touched when I see it. I also enjoy visiting smaller and lesser-known museums, like the Musée national Gustave Moreau in Paris, which was his house and studio.

JHI’ve visited it; it’s so special.

EJYes, it has a magical atmosphere.

JHTo finish up, I’d love to ask: What do you see as the role of art?

EJIt’s a source of new experiences and new emotions. It shapes not only our imaginations but our tastes and our points of view. Art can help us to understand the world more deeply. It allows us to access emotions, but perhaps even more importantly, it can help us understand ourselves. When it comes to my painting, I want it to surprise and intrigue the viewer, but also show how paintings from the past resonate or function in a collective consciousness, and how clichés and patterns are reproduced. I want the viewer to reflect on history and on methods of display, and I want to change commonly held perceptions about beauty. Of course, I don’t have any influence over how my work will be read. I can’t control that. But I do know that without art, the world would be a terribly empty place.

Ewa Juszkiewicz: In a Shady Valley, Near a Running Water, Gagosian, Beverly Hills, November 3–December 22, 2023

Artwork © Ewa Juszkiewicz

Jennifer Higgie is an Australian writer who lives in London. Her latest books are The Mirror and the Palette: Rebellion, Revolution, and Resilience: Five Hundred Years of Women’s Self Portraits (2021) and The Other Side: A Story of Women in Art and the Spirit World (2023).

Born in Gdańsk, Poland, Ewa Juszkiewicz lives and works in Warsaw. She earned an MA in painting from the Akademia Sztuk Pięknych, Gdańsk, in 2009, and a PhD from the Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Jana Matejki, Krakow, in 2016. Juszkiewicz began her female portrait series in 2011 and continues to explore the unsettling possibilities it holds out, evoking the uncanny without compromising the aesthetic harmony of the images from which she works.

On the occasion of Frieze New York 2021, the two artists discuss remixing conventions, the allure of Rococo, and the importance of research and history within their respective practices.

The artist elaborates on the creation of her first solo exhibition in New York.

Lisa Small, senior curator of European art at the Brooklyn Museum, considers the historical precedents for Ewa Juszkiewicz’s painting practice.

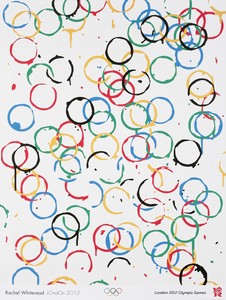

The Olympic and Paralympic Games arrive in Paris on July 26. Ahead of this momentous occasion, Yasmin Meichtry, associate director at the Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage, Lausanne, Switzerland, meets with Gagosian senior director Serena Cattaneo Adorno to discuss the Olympic Games’ long engagement with artists and culture, including the Olympic Museum, commissions, and the collaborative two-part exhibition, The Art of the Olympics, being staged this summer at Gagosian, Paris.

On the occasion of Art Basel 2024, creative agency Villa Nomad joins forces with Ghetto Gastro, the Bronx-born culinary collective by Jon Gray, Pierre Serrao, and Lester Walker, to stage the interdisciplinary pop-up BRONX BODEGA Basel. The initiative brings together food, art, design, and a series of live events at the Novartis Campus, Basel, during the course of the fair. Here, Jon Gray from Ghetto Gastro and Sarah Quan from Villa Nomad tell the Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier about the project.

Art for a Safe and Healthy California is a benefit exhibition and auction jointly presented by Jane Fonda, Gagosian, and Christie’s to support the Campaign for a Safe and Healthy California. Here, Fonda speaks with Gagosian Quarterly’s Gillian Jakab about bridging culture and activism, the stakes and goals of the campaign, and the artworks featured in the exhibition.

An interview with Marcantonio Brandolini d’Adda, artist, designer, and CEO and art director of the Venice-based glassware company Laguna~B.

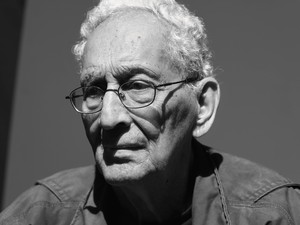

In celebration of the life and work of Frank Stella, the Quarterly shares the artist’s last interview from our Summer 2024 issue. Stella spoke with art historian Megan Kincaid about friendship, formalism, and physicality.

Multi-instrumentalist, singer, songwriter, and composer Lucinda Chua meets with writer Dhruva Balram to reflect on the response to her debut album YIAN (2023).

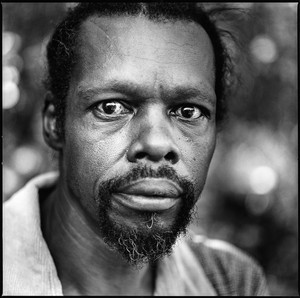

Lonnie Holley’s self-taught musical and artistic practice utilizes a strategy of salvage to recontextualize his past lives. His new album, Oh Me Oh My, is the latest rearticulation of this biography.

Richard Armstrong, director emeritus of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation, joins the Quarterly’s Alison McDonald to discuss his election to the board of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, as well as the changing priorities and strategies of museums, foundations, and curators. He reflects on his various roles within museums and recounts his first meeting with Frankenthaler.

Alice Godwin speaks with the choreographer about his inspirations from literature, visual art, music, and more.