Lisa Small is senior curator of European art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Transform, dissolve my gracious shape, the form that pleased too well!

—Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 1, AD 8

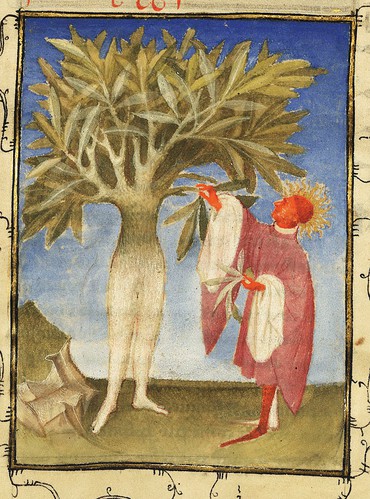

As the beautiful water nymph Daphne tries to escape a predatory suitor, the god Apollo, she makes this plea for help to her father, Peneus. Just as Apollo is about to capture her, Peneus, a river god, grants her wish by turning her into a laurel: her flesh becomes bark, her arms grow into branches, her feet turn into roots, and “her hair is changed to leaves . . . the girl’s head vanishes, becoming a treetop.”1

The striking and ambiguous work of Ewa Juszkiewicz brings back to me Ovid’s classical narratives of transformation and agency (or lack thereof), and their many representations over centuries of European visual culture. Juszkiewicz reimagines eighteenth- and nineteenth-century paintings of fashionably dressed women in ways that disturb the veneers of beauty and gentility. In the historical works, by artists such as Louis-Léopold Boilly, John Singleton Copley, Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, the ladies occupy customary settings: seated on plush furniture, or on hillsides with bucolic landscapes spread out behind them, or simply framed by a neutral background that emphasizes their colorful garments and artfully arranged hair. Their poses and body language are similar from one painting to another: they hold (but do not look at) books; rest their hands gently on pillows, tables, or in their laps; or carry flowers, fruits, or fans. We sometimes know their names, others are now unfamiliar, but, with few exceptions, their visibility in such portraits owed to their (socially and economically dependent) relationship with a man who wished to see them depicted this way and whose wealth was displayed through their finery.

A mood, color, or texture, an unruly strand of hair, or perhaps the arrangement of a bit of fabric: these are the qualities that might attract Juszkiewicz to a portrait. Studying it closely (she works mostly from reproductions), she meticulously renders the textiles and trimmings adorning the subject, skillfully emulating the original artist’s painterly techniques—but in her reinterpretations, the mostly anodyne faces of the original sitters (some bearing only the hint of a smile) are completely obscured, whether by swathes of fabric, intricately plaited hair, or, as with Daphne, an abundance of leaves. By disrupting traditional portrayals in this way, Juszkiewicz draws attention to the visual tropes that defined them, to the period’s societal expectations around women’s appearance and conduct, and to the possibilities those expectations reflected.

The painting Juszkiewicz references in Untitled (After Joseph Wright) (2020), for example, features a sitter wearing a voluminous dress known as a “drapery” that in Wright’s time—the work was created around 1770—was meant to evoke the fashions of the seventeenth century while showing off the eighteenth-century artist’s skill in rendering the sheen of silk.2 The lace-making tools the subject holds (but doesn’t look at), and the scissors and workbag on the table nearby, typify the kind of industrious activity that was admired and deemed suitable for women at the time. In Juszkiewicz’s painting these objects are still evident, but the sumptuous dress fabric has metastasized to envelop the sitter’s head, leaving visible only an errant lock of hair and some pearls.

Obliterated facial features can symbolize psychic erasure, and Juszkiewicz’s images visualize, with both the clarity and the strangeness of a dream, the regimes of fashion and comportment that have constrained women’s lives. But her project isn’t only about amplifying negation or limitation. She isn’t interested in reclaiming personal narratives, or in creating specific identities for her figures; rather, by exchanging the conservative, uniform ideal of likeness—which itself is a kind of mask—for wild foliage, tangled ribbons, or masses of hair, she seeks to grant them a sense of vitality and emotional authenticity. Paradoxically, Juszkiewicz reveals by defacement, evoking traditional portraiture’s fraught relationship between outward appearance and inner life. Like Cindy Sherman’s History Portraits (1988–90), which had a significant influence on the artist, these images foreground the ways in which representations of female identity are distorted and constructed.

The artist’s subversive imagery draws from Surrealist practices of appropriation and juxtaposition, and she is also inspired by contemporary fashion designers such as Rei Kawakubo and Iris van Herpen, who create alternative, nonstereotypical images of the human form through garments that embrace discontinuity, irregularity, hybridization, and biomorphism. She describes her visual interferences as “my protest against the stereotypical perception of femininity. By replacing certain patterns, I want to show women’s individual identity, complexity, and emphasize their uniqueness.”3 Displaced sartorial, tonsorial, and vegetal details may suggest hidden wells of passion and sensuality, or perhaps the transgressive or inverted identities temporarily granted in the masquerade assemblies and balls that were so popular in eighteenth-century Europe.4 Juszkiewicz’s transformations might even read as a kind of allegory: fantastical versions of the nuanced subjectivities and inventive selfhoods that (wealthy) eighteenth-century women might have been seeking in choosing to have themselves painted in the guise of Diana, Flora, or some other mythological or historical persona.5

But her imagery also alludes to misogynist notions around artifice, fashion, and nature that have long been used to disparage and limit women. These gendered constructs were potent in the eras of the portraits Juszkiewicz so evocatively deconstructs. And because she masks women’s faces with the very elements often implicated in these discourses—luxurious textiles, stylish coiffures, and leafy plants (signs of an eternally feminized “nature”)—her images are palimpsests through which such past cultural imperatives continue to reverberate.

The so-called Age of Enlightenment in the eighteenth-century period with which Juszkiewicz often engages witnessed a significant shift in the understanding of the relationship between biological sex and gender. An urgent desire emerged to delineate the qualities, interests, and demeanors that were “natural” to men and women, with the appearances of the latter being of particular concern: men were spectators, women were spectacles. Rationality and practicality were considered male attributes while women were judged irrational and silly. Vanity and a weakness for luxury and ornament had been considered “feminine” traits since antiquity, but in the eighteenth century these essentialist ideas found renewed strength around the burgeoning fashion culture that women were eagerly consuming. Fashion itself, including hairstyling and cosmetics, came to be conceptualized as feminine.6

Women’s apparent mania for fashion was perceived as a threat to the social order: in pursuit of new dresses they might trade their virtue or bankrupt their families, or they might use their fine clothes and cosmetic skills to deceive men. As one writer opined, “Women of quality in Paris display themselves . . . with a mind to taking liberties. They embellish their faces with a delicate pomade, and adorn their bodies with precious stones, whose brilliancy and flash dazzle the eyes. . . . One sees in them nothing but an agglomeration of snares, a tissue of artifices, their inflamed ambition makes them undertake the most extraordinary things in order to seduce the virtue of the grandees.”7 In fact women often instrumentalized their dress and hairstyles to express political allegiances or topical messages, or simply to achieve some measure of autonomy in a society that otherwise granted them little.8 But fashion was still widely condemned as at best frivolous and at worst an indecipherable agent of social and moral chaos: “Lift la mode’s masque and we will see that she is a hideous monster, a disorder without equal, and an abuse worthy of tears. It is impossible to depict her face because it is so plastered with make-up and covered with beauty marks that I cannot tell whether it is a human or a beast.”9 Masking, facelessness, confusion, and monstrosity: this charged language around women and their self-fashioning resonates with the unstable, unknowable identities of Juszkiewicz’s transformed apparitions.

That these sharply painted curls evoke seashells or finely wrought metalwork suggests that Juszkiewicz is as much engaged with still life as she is with portraiture.

The use of cosmetics, or “the vanities and exorbitancies of many women in painting, patching, spotting, and blotting themselves,” as the practice was described in a treatise of 1653 delightfully named The Loathsomnesse of Long Haire, was subject to particular disapproval.10 Although aristocratic Frenchmen had also worn rouge and face powder, by the mid-eighteenth century bright, unblended patches of red were primarily seen on the cheeks of women, where they suggested the glow of youth and health (in people who might possess neither), or perhaps the hectic flush of something more scandalous. Face painting was fashionable, despite being repeatedly equated with vanity and immorality (not to mention risk of poisoning from toxic ingredients such as lead). This assertion from more than a century earlier, which itself echoed longstanding denunciations, still held currency: “this painting and disguising of faces is no better than dissimulation and lying.”11 The connection between artists painting portraits of women and women painting their faces—both systems of deception—was widely noted in the eighteenth century, particularly as a way to denigrate such painters as François Boucher for their “effeminate” style, which many considered all surface and no substance.12

Beauty spots or mouches (flies) were another contested part of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century facial toilette. Popular with women of all classes (and some men), these small pieces of silk or velvet, affixed to the face with ointment, were fluid signifiers. Like tiny imperfections, they were thought to enhance attractiveness, as long as you didn’t wear too many of them at once, as the caption of one eighteenth-century French print of a woman applying them advises: “These artificial spots / Give more vivacity to the eyes and to the complexion / But by placing them badly, one risks / Blighting beauty with them.”13 It has been suggested that the position of such spots on the face was to some degree codified as a symbolic language of flirtation.14

These patches, though, were also associated with poor health: they could be used to cover blemishes or scars, or sometimes even as topical remedies for tooth- or headaches. They were also widely interpreted as signals of venereal disease; William Hogarth often dotted with black patches the faces of men and women whose corruption and downfall were the result of sexual misadventure. There was great concern about the social instability and moral decline that would occur if men were unable to differentiate between the uniformly painted and spotted faces of women of high and low repute, advanced and “appropriate” age, and good and ill health.15

Hair was another important site of women’s self-fashioning. Wild and orderly, intimate and public, hair lies on the blurred boundary between nature and culture. Women’s hair has been the focus of male anxieties around sexuality and power for centuries; one only has to think of the many laws across time and geography that have required it to be covered in public, or of the terrifying snake-haired figure of Medusa. In the eighteenth century, big hair was a marker of status; its complex arrangements and upkeep signaled both the labor required to create it and the leisure of the wearer. From the famed poufs of the 1770s and ’80s—“ridiculous edifices” (so called by a contemporaneous observer) built up to great heights with wool pads, powder, wires, and false hair, and festooned with fruits, flowers, and even stuffed birds or model ships16 —to the sculptural ringlets, knots, and braids of the early to mid-nineteenth century, arrayed across the head like topiary, perhaps no other female body surface was manipulated more flamboyantly or with so much artifice, as many satires and fashion plates show.

The ways in which the natural and the social collide and hybridize in Juszkiewicz’s figures seem to resonate obliquely with these Enlightenment self-fashionings, which provoked what one scholar has called a “pervasive anxiety about female surfaces.”17 In works such as Untitled (after Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun) (2019), for example, a few strands of hair escape from the fabric cocoon that encases the head and a tendril peeks out from behind the wrapped surface like a vestigial eyelash or brow. This may not have been Juszkiewicz’s intention, but the device conjures the measures taken by eighteenth-century women to preserve their extravagant poufs at night. As described in a contemporaneous account, they had to wrap their hair in a “triple bandage which everything [went] under, false hair, pins, dyes, grease, until at last the head, thrice its right size, and throbbing, [lay] on the pillow, done up like a parcel.”18

One of the artists whose paintings Juszkiewicz transforms most frequently is Vigée Le Brun, to whom she has said she “look[s] for a certain intergenerational relationship, sisterhood.”19 Le Brun eschewed the restrictive and ostentatious clothes of her time and claimed to wear only comfortable tunics, shawls, and turbans (which, though, would soon become very fashionable). Her memoirs recount how she styled her own sitters: “As I had a horror of the current fashion, I did my best to make my models a little more picturesque. . . . having gained their trust, they allowed me to dress them after my fancy. No one wore shawls then, but I liked to drape my models with large scarves, interlacing them around the body and through the arms. . . . Above all I detested the powdering of hair and succeeded in persuading the beautiful Duchesse de Grammont-Caderousse not to wear any when she sat for me.”20 Juszkiewicz often enlarges and extends Le Brun’s trademark scarf wrapping. In a second painting called Untitled (after Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun) (2020), which references the very portrait Le Brun described, a bit of the duchess’s natural, unpowdered hair takes its place among leafy fronds, lush grapes, and tied ribbons.

In what are arguably Juszkiewicz’s most unsettling images, she insinuates the (literally) outsized role that hair has played in articulating the female social body by completely replacing all facial features with dense locks. We seem to be seeing the back of the sitter’s head and the front of her body at once, as in the combined perspectives of Cubism. The styles are typically regimented, with precise partings, organized curls, or neat braids, but the hair is also rendered quite sensually, all soft, rounded surfaces and convolutions. Indeed, some of these hairy images bear more than a passing resemblance in form and feeling to an eighteenth-century print, erotic and satirical, of a female figure comprised only of an elaborately styled wig atop a bare derriere and legs wearing stockings, garters, and high heels.21

That these sharply painted curls evoke seashells or finely wrought metalwork suggests that Juszkiewicz is as much engaged with still life as she is with portraiture. Indeed, her paintings seem to address the relationship between those two genres—the way still lifes subjectify things and portraits objectify people, particularly women. These beautiful fruit and plant compositions also evoke the trope of women as belonging to nature, a historical stereotype and limitation that interests the artist. And in referring to still life they embrace a genre that, because academicians and theorists held it in lower esteem, historically posed the least professional and social difficulties for women painters.

Most pertinently, these still lifes are vanitas images. The opulent fabrics that cover the heads like shrouds, and especially the brown, mottled leaves amid verdant foliage, are there to remind us that earthly pleasures are futile, beauty is ephemeral, and all living things eventually wither and die. The word “vanitas,” from the Latin for “emptiness” and “falsity,” shares its etymology with “vanity,” leading us back to the discourses about fashion and deception that circulate around female surfaces. Like fashionable dress, cosmetics, and beauty patches, the ribbons, leaves, and swirls of hair on Juszkiewicz’s figures are unstable signs of concealment and amplification, assertion and contradiction.

1Ovid, The Metamorphoses of Ovid: A New Verse Translation, trans. Allen Mandelbaum (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1993), p. 24.

2See the “Catalogue Entry” section of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, website entry for Joseph Wright (Wright of Derby), Portrait of a Woman, c. 1770, available online at www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437954 (accessed September 6, 2020).

3Ewa Juszkiewicz, in an unpublished interview with Bill Powers, summer 2020.

4See Terry Castle, Masquerade and Civilization: The Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-Century English Culture and Fiction (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1986).

5See Kathleen Nicholson, “The ideology of feminine ‘virtue’: the vestal virgin in French eighteenth-century allegorical portraiture,” in Joanna Woodall, ed., Portraiture: Facing the Subject (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1997), pp. 52–72.

6See, e.g., Jennifer M. Jones, Sexing La Mode: Gender, Fashion and Commercial Culture in Old Regime France (Oxford and New York: Berg, 2004).

7Lapeyre, Les Moeurs de Paris, 1748, quoted in Melissa Hyde, “The ‘Make-Up’ of the Marquise: Boucher’s Portrait of Pompadour at Her Toilette,” The Art Bulletin 82, no. 3 (September 2000), p. 460.

8See Caroline Weber, Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution (New York: Picador, 2006), and Desmond Hosford, “The Queen’s Hair: Marie-Antoinette, Politics, and DNA,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 1 (Fall 2004).

9M. de Fitelieu, La contre-mode, 1742, quoted in Jones, Sexing La Mode, p. 15.

10Thomas Hall, The Loathsomnesse of Long Haire, 1653, 99, quoted in Rulon-Miller Books, “Hippier Hater,” available online at www.rulon.com/pages/books/46392/thomas-hall/the-loathsomnesse-of-long-haire-or-a-treatise-wherein-you-have-the-question-stated-many-arguments (accessed September 6, 2020).

11Hall, The Loathsomnesse of Long Haire, 1653, quoted in Caroline Palmer, “Brazen Cheek: Face-Painters in Late Eighteenth-Century England,” Oxford Art Journal 31, no. 2 (June 2008), p. 98.

12See Hyde, “The ‘Make-Up’ of the Marquise,” esp. p. 457.

13The print is Gilles Edme Petit’s Le Matin. La Dame à sa toilette, 1745–60, after François Boucher. Available online at www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/388453 (accessed September 21, 2020).

14See Peter Wagner, “Spotting the Symptoms: Hogarthian Bodies as Sites of Semantic Ambiguity,” in Bernadette Fort and Angela Rosenthal, eds., The Other Hogarth: Aesthetics of Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), p. 107.

15See Palmer, “Brazen Cheek,” p. 199.

16Madame Campan, Mémoires de Madame Campan, première femme de chambre de Marie-Antoinette, quoted in Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 54.

17Tassie Gwilliam, “Cosmetic Poetics: Coloring Faces in the Eighteenth Century,” in Veronica Kelly and Dorothea von Mücke, eds., Body and Text in the Eighteenth Century (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994), p. 144.

18Louis-Sébastien Mercier, The Waiting City: Paris 1782–88, trans. Helen Simpson (London: George G. Harrap, 1933), pp. 163–64, quoted here from Weber, Queen of Fashion, p. 111.

19Juszkiewicz, email to the author, August 15, 2020.

20Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, The Memoirs of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, trans. Siân Evans (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1989), p. 27.

21The print is Top and Tail, “Drawn by Mr. Perwig. Engraved by Miss Heel,” 1777. Available online at www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/391903 (accessed September 21, 2020).

Ewa Juszkiewicz: In vain her feet in sparkling laces glow, Gagosian, Park & 75, New York, November 17, 2020–January 4, 2021

Ewa Juszkiewicz artwork © Ewa Juszkiewicz