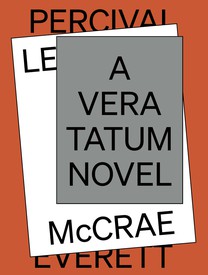

Christopher Bollen is the editor-at-large of Interview magazine. His third novel, The Destroyers, was published by Harper Publishing in June 2017. Photo: Sébastien Botella

Part One

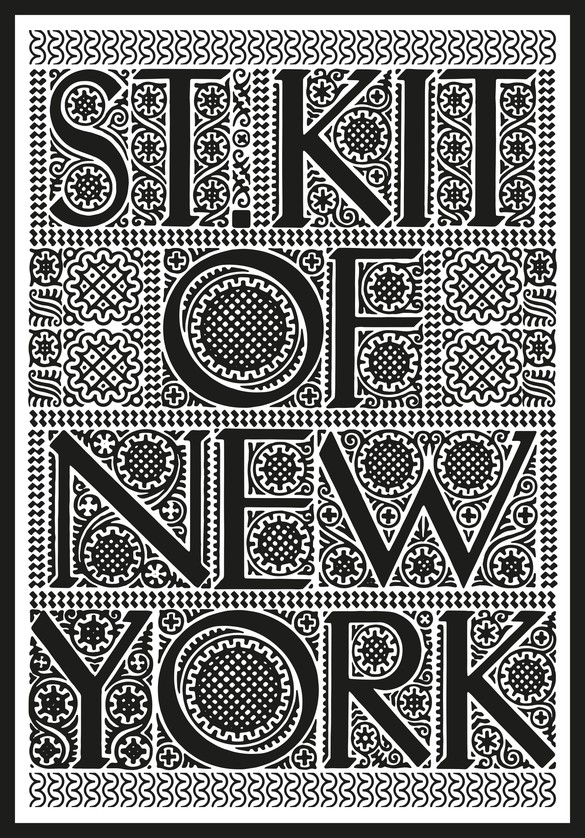

It would be an ordinary day, Kit decided, a sticky, late-spring New York day so unextraordinary and similar to all the others that it might as well be dragged into the spam folder of time.

She’d make a few calls, check in with her gallery to see which of her paintings had sold, meet up with Bruce for a late breakfast at Black Run to hear how his sobriety was affecting his sex life, return the ridiculous neoprene dress that didn’t fit and she’d already been photographed in, and get to her studio by mid-afternoon. If she managed not to be pushed in front of an oncoming subway—an achievement, given the recent rash of public-transportation homicides—today would pass into oblivion and she would rise again, single and productive and hungrier, tomorrow.

Kit yanked up the aluminum blinds on her bedroom window and watched the yellow light agitate the tip of the Chrysler Building. Across the street, the pretty hooligans of the Catholic high school congregated like rival gangs in a prison yard. For once, instead of wishing them dead for their loud morning hip-hop serenades, Kit tried to appreciate the way they modified their school uniforms with so many chains and rips and cinched folds to their skirts and pumpkin-sized sneakers that they utterly negated the whole purpose of a uniform. Maybe she’d paint their portraits and do a series called Youth at Risk that she could use for her show in Zurich next December. “Kit Carrodine traces the mutability of cultural consumerism by focusing on the appropriations of its youngest demogra—.” She had to resist the urge to pen her own press releases before she even began a project; it strangled the creative act from the start. Still, this was good, she told herself, bury your head in the future. Forget today. She walked into the kitchen to brew coffee.

Technically, the coffeemaker belonged to Kai, and she was thankful that he had overlooked it when he moved his belongings out of the apartment yesterday. They had been together for eighteen months. Kit treated her personal life the way others treated seasonal homes in the country. She disappeared so thoroughly into her paintings, months and months in her studio, that finishing a show was a chance to reconnect with her life and make the necessary improvements that had fallen into disrepair while she was away. Kai had been the first problem in need of fixing. While Kit had cast their breakup as an opportunity for them both to grow, she knew, and Kai knew, that she was dumping deadweight. She was successful, and Kai—all those awful, unsellable junk piles that he persisted in connecting to his Appalachian upbringing—was not. If she were to dwell on it, she would admit it was the cloying, singsong alliteration of their names, “Kit and Kai,” always uttered by a friend in a single breath, that proved the first blow to their happiness. Kit had not worked for years in this city to establish herself as an important painter to be referred to as a twosome that sounded like a demented Japanese toy. Still, the memory of naïve, vulpine Kai holding his box of clothes and books at the front door last night momentarily stung her. “You’re not even crying,” he had wailed with enough tears in his eyes for both of them. He was right. She hadn’t cried. And she wouldn’t today. She would get through this first day without regret. Plus, she missed dating women. Kai had always been a bit of a heterosexual experiment for her, like a home chemistry set that failed to turn salt into snowflakes.

Kit opened the front door and snatched up the Friday Times—surely there would be a review of her latest show. She let the advertisement inserts scatter in the hallway as she flipped to the art section. There was no review, and she felt small flares of jealousy over the triumphs of rivals. Why hadn’t Haskell, her gallerist, pushed harder for a review? He knew this was the show, the big one, the culmination of two years of work, and it had already been open for two weeks. Kit had painted a series of mug shots of New York death-row inmates among veils of fluorescent digital glitches and random free-floating emojis and consumer products. Perhaps Haskell was angling for a meatier story in the Times. In a small act of compassion for Kai, she considered it only fair that the first day of his misery wasn’t compounded by another validation of her accomplishments. Kit raked in about $2 million a year after expenses. She wondered what Kai would do now for money.

He had better not sell the drawings she had given him.

Forty minutes later, Kit was on the street, dressed in too-dense tweed for the soft April air pouring through the avenues. She carried the rumpled neoprene dress in its original shopping bag (in lieu of the receipt). The trees were breaking into pink, and the last-remaining magazine shops proclaimed the local headlines: woman pushed in front of D train, assailant not apprehended. Horrible. Horrible that these tiny, doomed magazine shops would morph into nail salons by summer. Even the banks were shuttering their storefronts, but somehow nail salons magically proliferated. The future was manicures. Kit tried to reach Haskell on her phone but got a busy signal. She wasn’t aware that the busy signal still existed. She tried again. Busy. Some idiot assistant had probably left the front-desk phone off the hook. The Haskell Vex Gallery might be too small an operation for her. She had stayed out of loyalty and expected devotion in return. Dammit, Haskell, pick up! She called his cell, but it went straight to voicemail.

Kit hurried down 10th Street, late as usual to meet Bruce. She wished she could text him calm down, a block away. But Bruce, a paranoid unemployed writer who lived off the chrome, manganese, and iron mines of his wrathful South African family, was religious about not using technology. It was noble only in theory. Though approaching fifty, Bruce had the healthy lust of a twenty-five-year-old just off the bus from Omaha, he had a fabulous wit and could always make Kit laugh before noon (not an easy feat, her sense of humor tended to kick in around sundown), and he had a house in San Sebastián where she was hoping to spend most of August. He would be thrilled to hear of her split with Kai (“He’s perfectly adorable, doll, in the one-night-stand, please-no-talking sense”). Kit scurried around the morning’s post–rush hour foot traffic. Everyone on the sidewalk seemed to have a disfigurement—a limp or a misshapen back or some invisible spinal condition that rendered them half-immobile. These were her people, New Yorkers on the street, drifting around the overtended brownstones like dirty pollen particles. She loved living here, though maybe not as emphatically as she had in her twenties; New York, you saved me was no longer a dissident shout but a quiet, grateful whisper like the kind exchanged between an older couple who had long stopped having sex and found their celibacy only confirmed their closeness. When Kit first moved to Manhattan, she had been a bar-back and a waitress. No matter how successful she became, a part of her always expected to end up back in the poverty of her youth. Artists understood starving even when they ordered endless lunch trays of sashimi for their studio staff.

Kit’s phone vibrated with an incoming call marked unidentified. It could be Bruce hounding her from a pay phone. Or Haskell calling from some provisional line if the phones were down at the gallery. She clicked “accept.”

“Hello?” she said. A muffled silence. “Bruce? Calm down. I’m a block away.”

She heard thundery pulses of static like panting breath.

“Hello? Who is this? Haskell? Hello?” A more depressing possibility occurred to her: Kai might have simply wanted to hear her voice. She had never been safe from his old-fashioned conception of romance. “Kai? Jesus, I said no communication. Why are you making this harder on yourself? This is for your benef—”

“Fucking bitch,” came the sexless, leathery voice. “You will die.”

At first she still thought it was Kai. But the primary-school, prank-call pathology didn’t fit the eighteen months she knew of him.

“You will die for what you did.”

“Thanks for the warning. I’ll have my assistant look into it.” She hung up. Unfortunately this was not Kit’s first death threat. Seven months ago, a leading fashion magazine had run a profile on the daughter of a maniacal, bloodthirsty dictator of a former Soviet state. In every photograph the handsome young woman had posed in her home in front of a prominent Kit Carrodine canvas. Kit had no clue how the painting wound up in the hands of the evil dictator’s daughter, and she went on a warpath straight to Haskell about it. “Secondary market!” Haskell had pleaded, arms raised in mystification, as if the secondary market were a divine force beyond control. “We’ll never again sell to the collector who flipped it.” The magazine suffered weeks of social-media persecution about their glorification of the offspring of a major human-rights violator, and it was Kit’s painting that appeared over and over alongside this blonde posed holding her infant baby while attempting to slip on a high heel. (It was the pose that infuriated Kit as much as the inclusion of her painting: why did a woman putting on an expensive shoe suggest the possession of a complex inner life?) The demons of social media briefly turned on Kit, as if she too were guilty of torture and kleptocracy by mere association. She had received dozens of frightening emails, a Twitter campaign to boycott her show at a Los Angeles museum, and thirteen hate-spewing anonymous phone calls. Her regular morning joke upon entering her studio had been, “Any calls for my execution today?”

If there’s one thing in this world you can count on, it’s a short attention span. The bluster didn’t slowly fade; within a week it vanished altogether and no one could recall the fashion story or the country of the dictator’s daughter or the beautiful painting hanging behind her. But Kit was sure there must be one holdout who had finally tracked down her number to burden her with a reminder. She circled through the revolving door of Black Run, theatrically swept the shopping bag over her shoulder, and located Bruce, clearly having failed in sobriety, slumped in a corner booth behind two glasses of white wine.

“You didn’t,” she roared from the doorway, ignoring the petite hostess’s attempts to corral her.

Bruce’s face lit up. “Of course I did. And I’m bringing you down with me.” He flicked the brim of the fuller glass.

On her way to Bruce, Kit passed a table where a couple she recognized sat. The woman was a prominent attorney and the man was on the board of MoMA when he wasn’t off on one of his spiritual quests in the desert. She idled at their table for a minute, swapping supple, meaningless banter. Kit wouldn’t exactly call them friends, although they were more than mere acquaintances. There should be a word for the people you genuinely care for, and enjoy talking to in snatches at a party, but who would not be expected to attend your funeral. Kit said goodbye, glided toward Bruce, and bent down to kiss him on each cheek. When she squeezed his shoulders, he winced.

“What’s wrong? Did you get beaten up by a new boyfriend?”

“No, by my trainer. Every muscle is sore. And you’re late. Again.”

“I’m sorry,” she said, sliding into the seat across from him.

“That’s all right. I ordered company.” He grabbed his wine and took a sip. She gave him a disapproving glance, but she wouldn’t guilt-trip him about it. She loved Bruce enough to tolerate his vices. She might not even recognize him without them.

“I got another death threat.” She enjoyed saying that. It made her feel strangely important. Bruce’s eyes widened with fascination.

“You might be the only artist in the world worth killing. At least your work means something to strangers. You should take it as a compliment.”

“I’ll try to see it that way.”

“I had such a marvelous time at your opening. What a crowd. I could barely see the paintings.” He leaned into the table to signal intimacy. “Doll, I promise I’ll go back to the gallery when I have a free hour to really take them in.” Bruce had all the free hours of every day to do just that. It was as if he, too, were waiting for a positive review to make sure a second trip was worth his while.

“The show’s up for two more weeks. No word from the Times yet.” She huffed and reached for his hand. “Honestly, I need that review. I want the work to get some notice. Otherwise it will just be sold to private collections and no one will ever see it again. What’s the point?”

He rubbed her knuckle tenderly. “Everything eventually moves through the intestines of private ownership and ends up in public institutions one day. Meanwhile, think of the collectors as guardians. Or as benevolent digesters.”

“You make museums sound like toilets. Anyway, that’ll be in, like, forty years. I want them seen now. They’re supposed to be about the Internet. In forty years they’ll be as relevant as the statues at Luxor.”

Bruce retracted his hand. “That’s a sensitive subject. I had a friend—now who was it?—a distant uncle, I believe, who survived the shooting massacre at Luxor. He hid behind a rock for hours, and—”

“Bruce,” she howled. “That was my story. It was my friend’s sister, or was it—oh, I can’t remember. But I told you that story.”

Bruce stared down at his lap in genuine hurt. He loved to tell stories and hated when he was called out on pilfering them from others. Kit sighed and feigned confusion. “Maybe I’m wrong. Tell me again. What was it?” She was absolutely sure she had told him that very story a few years ago over dinner. Bruce immediately snapped to attention, describing the scene of the massacre at the archaeological site with a wealth of gruesome adjectives. Kit pretended to be astonished and actually found herself shocked the moment he mentioned the bullets piercing the tourists as his distant uncle—who was really Kit’s friend’s sister—crouched behind a stone pillar. “Awful,” she whimpered as if hearing of their deaths for the first time. He nodded solemnly.

“The worst,” he agreed. Although now she recalled that Bruce’s reaction was an apathetic shrug when she had described the same piercing bullets to him. It only mattered to him when he told it.

“Well, you’ll love my news,” she said. “Kai and I . . . . ” But her phone began to vibrate on the table. When she flipped it over she saw it was her studio manager, Grace. She lifted the device to her ear. “What?”

“I’m sorry to bother you,” Grace said too meekly. Grace was past the point of doing anything right—everything the girl did was too. She was another problem on Kit’s list of life repairs. “It’s just that I’m getting all these weird calls from journalists. They want to talk to you. I didn’t know what to say.”

“Say yes,” Kit shouted. “That’s good news, Grace, not bad news. We want that.”

“But the questions were really weird. I mean, I didn’t understand them.” Grace would never understand. So much for the practical application of an art-history degree. “It was the Post, the Daily News, Jezebel, and Huffington—”

“I’ll talk to them.”

Grace hesitated. “But. . . I think there’s something wrong, something odd. You should call Haskell.”

“Why?” But Kit decided that, for once, Grace was correct. She hung up and dialed Haskell on his cell. I’m sorry, she mouthed to Bruce and placed her wine glass in front of him to keep him occupied.

Haskell answered after four rings.

“What’s going on?” Kit barked. “I’ve been trying you all morning.”

“Oh, um,” Haskell mumbled. “Oh, Kit. It’s been so crazy here at the gallery.” He sounded nervous and tense, a middle-aged man who had lost his cool. Haskell never lost his cool. She had never seen him so much as sweat. That was one of the reasons she had stayed with him. “I was going to call. You see, it started two days ago. I honestly thought it had something to do with the humidity in the gallery. Or condensation from the air conditioning. So I wasn’t going to bother you. But it’s. . . . it’s not that.” He shouted something indecipherable at an assistant and then whispered into the receiver. “I think we should close for a few days, until an expert can come in.”

“What are you talking about?” Now she sounded nervous and tense. “Close the gallery? No way. You’re not doing that. What the hell is the matter?”

“I. . . I can’t explain it. Something’s wrong with one of your paintings. I think you should come down and see for yourself.”

Kit double-kissed Bruce goodbye and collected her shopping bag, apologizing to him while frantically ordering an Uber. Black Prius. Driver’s name Mamoun. The one problem with Uber was that you couldn’t bribe the driver to speed faster to Chelsea. Kit climbed out of the car on 21st Street and ran down the bleached sidewalk. As she approached Haskell Vex she was struck by a bewildering sight: a line of some thirty people waiting outside the frosted-glass doors to see her show. A rush of ecstasy flooded through her, but these loiterers weren’t the usual, well-heeled, semijaded gallery-goers of strictly Northern European ancestry. They were of all ethnicities and mostly very old or very young, with patchy clothing, and some held rosaries and others white roses. As she sprinted past them she heard one of them whisper, “She’s the one.”

Kit wrenched open the heavy door. Inside the cold white space was a crowd of more unlikely visitors. Some clutched hats reverently over their hearts. One older Hispanic woman was on her knees in the midst of some sort of Bellevue-worthy emotional breakdown. A tall black man was passing out leaflets printed with a calligraphic verse. Two gallery assistants stood at the front desk looking horror-struck. She spotted Haskell stampeding toward her. He grabbed her by the arm before she could ask what was happening. His face was ashen and, yes, sweaty.

“Kit, let me show you. It started two days ago and it hasn’t stopped. I have to say, I do not want this.”

As they entered the main exhibition room the swarm of visitors fell into a hush. Kit gazed at her nine paintings lining the walls. All of them were perfectly normal except for the one on the far wall. There were clumps of white roses underneath it and three more women swaying on their knees. The painting was Untitled, #7 in her Killers series. Kit had covered the canvas in a golden wash. Amid the floating emojis of a bag of cash, a priapic eggplant, and a beach umbrella loomed the mug shot she had lifted from public record of a young black prisoner convicted of murder, whose name she never knew because his particular identity had been of no interest to her. But as she stepped closer, she saw exactly what had brought all of these visitors to Haskell Vex in droves. Her lips went numb, and the shopping bag fell from her grip. No, fuck no, it’s not possible. A seepage of water clung to the young man’s eye, and a tiny amount trickled down the canvas, bleeding the gold. The man in the painting was definitely—unmistakably—crying.

Haskell turned and looked at her angrily as if expecting her to offer an explanation. But Kit Carrodine was not in the business of explaining her artwork, let alone miracles. She stood in the cold room full of people she didn’t recognize, a little Lourdes right here in Chelsea, and all she could think was how happy she’d been this morning, before God came to the art world.

[To be continued]