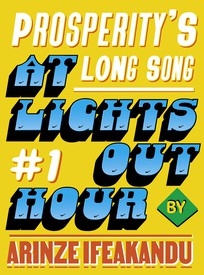

Christopher Bollen is the editor-at-large of Interview magazine. His third novel, The Destroyers, was published by Harper Publishing in June 2017. Photo: Sébastien Botella

Part Two

Know this: Kit was not a believer.

Sure, at thirty-four, she had witnessed her share of miracles. The summer after college, she and her German girlfriend Gudrun had spent an entire night climbing Mount Sinai to reach the peak at sunrise—the apocalyptic purples and dusty apricots pouring across the dawn-bleached desert still haunted her. Six years ago Kit had overslept and missed a train in Madrid that was subsequently bombed by radical separatists; she still had the train ticket pinned to her bulletin board. Her Korean mother in Baltimore had been diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer (the five-year survival rate was less than 10 percent), but wondrously, after only two operations, she was in remission and running mini-marathons. Last winter, while visiting a wealthy collector in Hawaii, Kit had gone for a swim alone and had actually touched a wild dolphin.

These, according to Kit, were extraordinary events; they were implausible and suspicious-sounding but genuinely authentic moments of real-life enchantment. Kit often leaned on these experiences to remind herself that the world still held a cache of magic and mystery, and she occasionally brought out one of these anecdotes at snoozy cocktail parties to entertain listeners. But these were terrestrial miracles, requiring no outside tampering by the Divine. Like anyone in New York who made serious money by exploiting their own talents, Kit felt that she was a chosen person—she might even go as far as to call herself blessed. But God? A maker of supernatural miracles? A mystical visitation by a holy being who, amid the extreme turmoil befalling this planet, chose a Kit Carrodine artwork to spiritually vandalize? Uh uh. No frigging way.

The problem was that one of her paintings—Untitled, #7 of her Killers series, now hanging at Haskell Vex Gallery—was crying, as in leaking water from the eye region. And in the days that followed, no matter how many times Kit swore up, down, and sideways that it was just a case of condensation buildup—a freak accumulation of vapor thanks to the Antarctic temperature at which Haskell set his gallery thermostat—the blogs and newspapers went berserk covering the miracle painting of West 21st Street. There had been articles in the New York Post (surprisingly unbiased), The Cut (a mocking one), Jezebel (even more mocking), and The Daily Beast (a think piece on the mingling of true belief and predatory capitalism). In an attempt to turn a quotidian environmental disturbance into abject sensationalism, the reporters refused to heed Kit’s appeals to sanity—Condensation, it’s only condensation!!! The gullible faithful came in droves to the gallery while the rational skeptics accused both Kit and Haskell of attention-seeking charlatanism. The final irony had not been lost on her: she had prayed for the blizzard of press she was currently receiving—the story had even drowned out news on the search for the New York serial subway pusher—and it was this very exposure that was threatening to destroy every last shred of her credibility in the art world. Last week she had been a serious artist and a rising star; this week she was a local carnival act and a falling meteor.

If Kit ever did meet God, she would punch Her/Him in the stomach (after thanking Him/Her for sparing her mother).

Kit ascended from the tomb that was the Greenpoint Avenue subway stop. One sleeve of her nubby beige cardigan was bunched at her elbow while the other engulfed her blood-speckled fingers: she had chewed three hangnails on the ride to her studio while refusing to look at any of the newspapers folded in the laps of her fellow riders. Before reaching her studio in a former soap factory on the waterfront, she predicted that the steel grate would still be shuttered over her door. That would indicate that the last of her assistants had fled the sinking ship—two had quit by email yesterday and one had concocted a weeklong family emergency in Minnesota that was so deranged it almost sounded credible. To her genuine surprise, though, the grate was lifted. She entered the cavernous concrete rectangle. Its floor was stained in spray-painted outlines of long-removed canvases, not unlike, Kit always thought, police tape around homicide victims.

Usually Kit’s first sight of her studio manager, Grace, was the emotional equivalent of rubbing alcohol on a cut. But today Kit was touched by Grace’s loyalty in showing up. Kit smiled in gratitude even as the young woman was sweeping up slides she’d obviously toppled onto the floor. From here out, Kit promised herself, she would no longer take her staff for granted. She vetoed the plan to fire Grace; instead she might offer her a raise.

A mug of tea sat steaming on Kit’s drafting-table desk, clearly placed there by Grace (who really was a wonderful, brilliant studio manager). Kit noticed the mug was bleeding a water ring onto page four of the Daily News. “Heaven help us! Prominent New York artist’s miracle painting cries crocodile tears, says gallerist.” Says gallerist? Kit quickly scanned the article, rummaging her eyes over the five paragraphs for Haskell’s name. And there it was, two paragraphs in: “Mr. Vex assured reporters that the painting is a clever hoax, perhaps intended by Ms. Carrodine as a sly reference to medieval church statuary. He refused further explanation as to the source of the strange tears.”

Kit felt as if a bullet the size of a taxi had just plowed through her body: Haskell was supposed to defend her, not throw her under the nearest bus. She dialed the gallery on her cell phone. As she waited for someone to pick up, she stared at the two images accompanying the article. One was a photograph of her from a year ago at an opening at the Whitney Museum—not an unflattering shot, in which Kit posed with an annoyed-but-humored crumple to her lips. The paper had cropped in on her, cutting the face of the man next to her in half. It was her ex-boyfriend, Kai. He was grinning open-mouthed and his one visible eye was roller-coastered wide; he looked like a fool, but a fool she missed. She wondered how he was handling their breakup. She could have used Kai by her side and in her bed the past few days, someone gentle to steady her erratic brainwaves. Kit took a compact mirror from her purse and placed it perpendicular to the cropped photograph, doubling the half-moon face, briefly returning Kai to the illusion of a complete person.

“Haskell Vex Gallery, please hold.”

Kit was thrown into the purgatory of badly dated indie rock. The second image that the Daily News ran was a reproduction of Untitled, #7, pretears. Kit examined her own painting, gazing past the forest of emojis—cash bag, eggplant, beach umbrella—and down to the barely visible face of the young black murderer. She had studied his mug shot for weeks while painting it, duplicating every wrinkle and bend of his mouth and nostrils. Kit probably knew this man’s face better than anyone else on the planet, maybe even better than he did. Were inmates allowed mirrors on death row? It was a tough face, menacing but resilient, with a wide jaw and forehead and the disbelieving eyes of someone who realized he was caught whether or not he was guilty. She didn’t know his name or the particulars of his crime—when conceiving the Killers series she had found it meaningful not to know his name or background, to treat him as the state did, another statistic to be processed and incarcerated.

“Haskell Vex, thank you for holding,” a voice chirruped through the receiver.

“This is Kit Carrodine. Get me Haskell immediately.”

“Oh,” moaned the assistant. Oh, as in, the problem is calling. “Umm.” Kit was losing her patience. “He’s gonna have to call you back. He’s in a meeting.”

Patience. Breathe. “Listen. What’s your name?”

“Marcella.”

“Hi Marcella.” Kit was preparing her standard pecking-order retort: Just so you know, Marcella, it’s my art on the walls that allows Haskell to pay you to sit up front and look pretty while pretending to read Deleuze and put me on hold. So do me a favor. Tell Haskell he has two minutes to find the door to his meeting room and call me back. But Kit found that for once she didn’t have the nastiness in her. She just said limply, “Could you please ask him to call me as soon as humanly possible.”

She looked out the window at the skyline of Manhattan shining in the spring sun, the slender skyscrapers with steeples and spires, like gilded granite churches. Deep in the cracks of that metropolis, the trees were budding pink and yellow. It had only been a few horrific days, she told herself, don’t let a week be a life sentence. The miraculous tears will stop and life will go on. Kit considered buying a plane ticket to some faraway destination until the scandal blew over—Palermo or Baia do Sancho or San Sebastián, or hadn’t she discovered via Facebook that her old girlfriend Gudrun had opened a bed-and-breakfast in Munich? But she rejected the fantasy of escape. Kit, like all successful New Yorkers, was at heart a survivalist and she knew she’d stand her ground.

“Excuse me,” a frail voice whispered behind her. Kit spun around to find Grace standing a foot away, shoulders hunched and purple-white hands held like a frozen clap at her waist. “Could I talk to you for a moment?”

“Of course,” Kit wheezed, in a tone she hoped sounded like affection. “I’m always here for you. What’s on your mind?”

Grace nodded toward page four of the Daily News. “I feel terrible about what’s happening and all the negative attention you’re receiving.” Grace was putting it mildly—four art magazines had canceled features and there had been all of zero reviews of the show. The art world had unanimously shunned any mention of Kit Carrodine for fear of contamination. To them, Kit had committed the mortal sin of stirring the passions of the masses. “It’s just that”—Grace put her hand on her forehead as if gauging her own temperature—“I’ve been having to handle all of these crazy calls from religious people this past week.”

“I told you to tell them, condensation!”

“I have,” Grace swore. “But people on the phone are praying at me. Asking me to pray with them. And those are the nice ones.” Grace blushed. “There have been angry ones too. Accusations.”

“Like what?”

“Just—” Grace stumbled, afraid to broadcast those insults to their intended target. “It doesn’t matter. Look, I really admire you, and I know none of this is your fault. But I think I need to tender my resignation.” Kit reached for Grace’s tiny hands but the young woman recoiled. “I never told you this,” Grace continued, “but my family back in Colorado Springs was really Christian.” Grace’s eyes glistened. “It was hard for me to get away from that. Really hard. And now all this talk about miracles is making me feel super uncomforta—”

“Please don’t leave me.” Kit was taken aback by the spontaneity of her own pleading. She tried for control as she repeated, “Please don’t.” A call came in on her cell and she instantly picked it up, hoping to hear Haskell on the other end. It was not Haskell.

“You disgusting, evil cunt,” growled the sexless leathery voice. Her death-threat caller was back. “Shame on what you did. You will die for this.” Kit hung up without uttering a word. Announcing that someone wanted to kill you for your wickedness was not the secret to wooing disgruntled employees. It took ten minutes of begging and nodding and sharing horror stories from youth—and also the promise of a raise—for Grace to agree to stay. After they shook hands, Kit lifted the Daily News article and pointed to Untitled, #7.

“This painting,” she said. “Do we still have the original mug shot in our files?”

Grace bit her lip. “I think so. I can look. Toby was in charge of—”

“Can you dig up the identity of this convict? Find out his name and where he’s in prison. And any information on the crime.”

Grace nodded. “I forgot to mention,” she whispered sheepishly. Kit worried she’d ask for more vacation days. “Kai keeps phoning too. He says he needs to talk to you. He’s—”

“No,” Kit replied definitively. She resigned herself to getting through this crisis on her own.

When Haskell finally called, Kit barked his newspaper quote at him. “A clever hoax?”

“What was I supposed to say?” he snapped. “Should I have admitted that it might be a sign from God for all I know?”

“You were supposed to say condensation! Because that’s what it is.”

“But it isn’t!” he roared. “I’ve had four of the city’s top heating and cooling experts into the gallery to check the equipment. Everything’s normal. Each expert guarantees that isn’t what’s causing the tears! 100 percent no! It has nothing to do with the conditions of the gallery. Don’t you dare try to pin it on me!”

So this was how her eight-year partnership with Haskell would end: wrestling over who would take the blame.

“What are you saying, Haskell? If it isn’t condensation, then are you trying to tell me it is a miracle?” Haskell laughed. It was the dry, mechanical laugh of an empiricist, a realist, a man who did not for a split second believe that the world was run by much more than chaos and the gravitational tug of the sun. “Whether or not we have proof of the gallery’s humidity levels, you could have just said it was condensation and the whole circus would have vanished.”

“No, Kit, I’m not taking the blame,” Haskell hissed. “I’m not ruining my reputation to save your ass. If I take the rap for this shit storm, every artist I represent will be walking out the door or demanding an entirely new gallery due to my negligence. I can’t afford it! I’ve already taken a loss, and I don’t simply mean in terms of respectability. None of your paintings has sold. No collector in their right mind wants to get ten feet near a series that’s become a laughing stock. My only chance of a profit is selling Untitled, #7 to a southern mega-church! No, it’s your painting, your fault.” Haskell took a long, well-deserved inhale, having fatigued on a rant that Kit wished had been a few degrees less accurate. The Haskell who spoke next was more considerate, and Kit tried to forget the ugliness of five seconds ago. “Look, it isn’t good. But I am on your side. I’ve found a conservator in Los Angeles who is flying in tonight to examine the painting.”

“Why not a conservator based in New York?”

Now Haskell was frugal about his insults. “No one decent here was willing. This woman is a pro and she’ll do it discreetly. And when we find the cause, we’ll notify the press. Basta! This lunacy will stop once and for all. Now, do I have your permission for the conservator to run tests tonight on Untitled, #7? Legally I need your permission.”

“Yes,” she relented. Yes, he had her permission. The conservator could chip the whole eye off the canvas as long as she uncovered the source of the water. “How are the crowds?” she asked. “Is it still a Catholic mass at the gallery?”

“I hired guards to keep them out,” Haskell said. “I couldn’t allow it any longer. These people on their hands and knees, singing hymns and weeping, when I’m trying to run an art space. As of this morning, none of them is allowed inside. They weren’t pleased. Your parishioners are congregating at 7 pm in the basement of St. August’s over on Seventh Avenue. Kit, I don’t know if you’re up for it—” He paused.

“Up for what?”

“It might not hurt for you to go there and make an announcement. Tell them it isn’t a miracle. Tell them you used special paint. Hell, tell them one of your assistants was sneaking in and throwing water on the painting. It could really help in terms of disbanding the pilgrims. And who knows? Maybe it isn’t too late to patch this hole in your career.”

—

The subway had only gotten as far as Third Avenue before an announcement came over the speaker that “due to a criminal incident,” service was temporarily suspended. As Kit was climbing the steps to the street, a heavyset woman in a macramé coat nodded to her and said, “Someone was pushed in front of the subway at Union Square!” Kit asked if the perpetrator had been apprehended, but the woman just shrugged—“Same ol’ dangerous city of psychos,” she said, and shuffled off. Was it evil that Kit hoped the latest attack by the subway pusher might steal the attention away from her ridiculous crying painting? Maybe her salvation was this serial murderer—maybe killers did provide some essential benefit to humankind?

Kit walked the fifteen blocks to St. August’s. Because of the stalled train, she was half an hour late meeting Bruce, who was leaning against the church’s wrought-iron gate with his hands in his jean pockets and his black-leather jacket zippered to his chin. Bruce had been the only friend Kit could think of who’d be willing to attend the meeting with her. He tapped his watch and she waved her hands in apology.

“I know,” she called. “I’ll pay for the wine after.” She kissed his cheeks.

“The real miracle would be your punctuality,” he complained.

“Ha ha,” she said. “I don’t know why I’m doing this. I don’t want to face a room full of lunatics who should be permanently committed for believing that a gob of oil paint applied to Belgian linen is capable of showing emotion.” She shook her head and looked at Bruce, expecting him to reply with an even more cutting remark. Instead, he squinted at her sadly.

“I think it’s beautiful what you’ve given them,” he said simply, “and what they’ve given back to you in return. Just because it isn’t the people you expected to react to your work—”

“Don’t do that,” she warned him. “Don’t play devil’s advocate just to be provocative. This idiocy over a trickle of water is destroying everything I’ve worked for. It’s not funny.”

“It’s not funny,” he agreed. “But Kit, artists don’t get to choose their audiences, nor do they own the rights on what their work comes to mean. You should respect—” Bruce cut off. He must have caught the anger brewing on Kit’s face and decided she wasn’t up for an evening seminar on art and ethics.

“Let’s get this over with.” Kit stormed toward the doors of the church with Bruce racing behind her. They located the staircase in the vestibule and descended together in the dark. Kit heard the singing first, hymns about the Lord and mountains falling to dust. Bobbing candles painted tiger stripes on the walls. When they reached the bottom and turned a corner, they entered a cafeteria filled with sixty or seventy candle-lit bodies. There were all races, all ages, and, Kit assessed, mostly the lowest fourth of the city’s income spectrum. Some held posters of Untitled, #7 amateurishly photographed or blown up from the Daily News article. A few had glued blue yarn running down from the convict’s right eye. Kit turned, considering escape over the planned announcement that the tears had been a prank, but she was already spotted. A cute Chinese girl came up to her first, grabbed her hand, and kissed the knuckles. Kit almost pulled her hand away but didn’t. An ancient woman in a wheelchair was zooming toward her, the tears on the woman’s face rerouted by the deep wrinkles of a smile. Within a minute, Kit was swallowed by her fans, thanked and hugged tenderly and palmed on the back. People were crying all around her, and a lean white man was so overwhelmed he could barely tell her that she had restored his faith in a better life after this one.

“I really didn’t do anything,” she tried to explain. “You see, I’m an atheist. It’s all been—”

“God performed the miracle, yes, but you created the stage.”

An attractive, elderly black woman in a lavender suit was marching toward Kit. The woman’s arms opened and, before Kit could protect herself, she was consumed in a tight embrace. Kit felt the heaving breasts and the sticky smell of perfume. The woman touched her cheeks, staring up with love.

“Thank you,” the elderly woman sobbed. “I can never repay you for what you’ve done. Neither can Ronell.” Kit was on the verge of asking who the heck Ronell was, as well as clarifying that this had all been an embarrassing mistake. But Kit didn’t ask or clarify. And because she didn’t, her entire life changed: “How did you know to paint him?” the woman went on amid sobs. “How did you know he is innocent? My boy never murdered anyone, but the police didn’t listen. The police didn’t listen because they needed someone to be guilty.” Moans of agreement trafficked around them. “Only now, because of your painting, your miracle, the world has started to pay attention to his case. You have given Ronell what no one else ever dared. A chance. Oh, bless you. You have been sent as a savior of truth by the Lord.”

Kit stepped out of the church into the blue-black evening where her phone found reception. She dialed the number and waited for an answer. Haskell said hello.

“Call off the conservator. You no longer have my permission.”

“Kit.” He sounded startled. “She’s just arrived. Don’t be silly.”

“I will sue the fuck out of you if she touches that painting.”

“Are you on drugs? Have you been drinking? Kit, are you stoned?”

“It’s a miracle, Haskell. It’s a miracle as long as it can’t be explained. Call her off. The painting is crying.”

[To be continued]