As the Keith L. and Katherine Sachs Senior Curator of Contemporary Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Carlos Basualdo has organized the exhibitions Bruce Nauman: Topological Gardens (2009), Michelangelo Pistoletto: From One to Many (2010), and, with Erica F. Battle, Dancing around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp (2012).

Founding director of Gagosian Rome, Pepi Marchetti Franchi has overseen more than forty exhibitions at the gallery since it was established, in 2007. Raised in Rome, she spent many years living in New York, including the eight years she was working at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: Andy Massaccesi, courtesy Mutina

In an oeuvre spanning almost fifty years, Giuseppe Penone has explored the subtle levels of interplay between humans, nature, and art. His work represents a poetic expansion of Arte Povera’s radical break with conventional mediums, emphasizing the involuntary processes of respiration, growth, and aging that are common to both human beings and trees, with which he is so deeply involved. His works can be found in many major museum collections around the world.

PEPI MARCHETTI FRANCHIAs the editor of this book, how did you first approach the project?

CARLOS BASUALdoI started by identifying the needs of those who might want to learn more about Giuseppe’s work—scholars, collectors, the general public. When we began discussing the project in earnest, I was struck by the fact that there was very little in English that took into account the full complexity of the work, none that grasped the work comprehensively.

PMFYour approach structures the book into two parts. The first volume contains many different perspectives on the work, including authors who have different professions, backgrounds, and bases of knowledge. The second component, a series of eleven booklets, explores the core themes and interests that Giuseppe has carried through his career. That overall view reveals, among other things, how the work often develops in series or families through which, Giuseppe, you explore an idea, or the potential of a material. Your interest in the branches of trees, say—in a way all those branches grow out of the same trunk, but they develop quite independently. Showing trees stripped of their bark, for example: you began that practice very early on and you’re still moving forward with it.

GIUSEPPE PENONEIt’s often a question of rediscovering the form that is already present within the material. In the case of those works, it’s about discovering the tree as it was at a certain point in its growth.

CBThis book will be very different from any earlier publication on the work, mostly because of how we articulated this possibility of a more global perspective. For the first part of the book, we worked with writers who I thought represented the different worlds that have come in contact with Giuseppe’s work—the French context, for example, which is extremely important in relation to an understanding of Giuseppe’s work. Giuseppe has had a number of very important shows in France, from the retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 2004 to the major exhibition at the palace of Versailles in 2013. There is a large body of writing on Giuseppe in French, not only by art historians but by philosophers and others. So the book includes a wonderful essay by Rémi Labrusse, who knows the literature thoroughly and will thoughtfully address it as well as the work itself of course. Then there’s Emily Braun, one of the most important American scholars of Italian art and the curator of the excellent Alberto Burri retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York last year—I could not leave her out of a book of this kind. We also very much wanted more varied perspectives, so we invited, for example, the British scientist Timothy Ingold, whose field is social anthropology—a field of knowledge that has allowed him to tap into Giuseppe’s work in a way that enriches the debate enormously.

We realized that it was crucial to accompany these different perspectives with a comprehensive overview of the work, which we thought needn’t be chronological but had to be systematic. We then proposed making a booklet dedicated to each major theme in Giuseppe’s work introduced by a text by Daniela Lancioni. Daniela is an Italian scholar who has worked with Giuseppe for many years. For the second part of the publication, Daniela has developed a series of chapters that let the reader follow the various directions the work has taken over time. These, then, are the two parts of the book—on the one hand different perspectives on the work, coming out of different cultural worlds and different contexts of reference, and on the other an overall analysis of the work, structured in separate chapters and punctuated by texts by Giuseppe that I have selected from his own writings.

We wanted the structure of the book to correspond as much as possible to the structure of the work. Since the form of Giuseppe’s work has much to do with its intellectual structure, we wanted to try to get closer to that in the book as well.

GPYes. At the same time, I think the way to address the work is by talking about sculpture. Knowledge of materials, and the pragmatic aspects of making the work, are fundamental for me. They’re how I understand why one work has one form and another has a very different one, even though the basic concept that generated them is the same.

PMFThey’re different aspects and moments of an experimentation that stems from the same intentions.

GPThat stems from intentions and also from doing—from the direct relationship with the material. This, I believe, is what gives the work its character. I don’t take a literary approach to form, I try to understand a language that talks about doing, and about the form that can be developed from the material itself.

CBUnderstanding through doing, and it’s the process of doing that develops form.

GPYes, and that form is almost always already present in the material.

PMFSo it’s a question of revealing something already there in the material, something you establish a dialogue with.

GPThe interesting thing about this book is the way it looks at the work. This collaboration with Carlos is completely different from other experiences I’ve had: it approaches the work by analyzing it as a totality not only through the vision of an art historian but through an examination of its context, an attempt to explain why it has the specific identity it does, being tied to a region, a particular culture, that of Italy and the Mediterranean. That doesn’t always happen—there’s a tendency to isolate the work, to insert it into the context of a single aspect of art history, whereas it’s obviously in dialogue with reality and with everything that goes into making up that reality. This approach is also developed through the book’s form, its concept, its design—the design marries perfectly with that idea.

CBYes, the form of the publication as an object was key to us, we discussed it at length, both among ourselves and with Paul Neale, our wonderful graphic designer.

PMFGiuseppe, your work is recognized internationally and has been very influential for many younger artists. Is there anything you think has been overlooked at all? Anything this book could focus on or correct?

GPEvery book is necessarily partial, it can’t cover everything. But the strength of this one is that it addresses the problem of dealing with the work from different viewpoints, analyzing it in a way tied not just to art history, or to any one specific context. That enriches the work a great deal. The book basically synthesizes the concerns I myself have had in making the work, which haven’t always come from the world of art history but also, perhaps, from philosophy, or from literature. In that way the book mirrors a reality in the work and enriches its interpretation, opens up other possibilities of analysis. It is always the moment that is lived that suggests the reality that is seen.

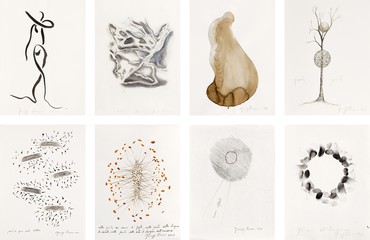

CBI absolutely agree. One important element that emerges clearly from the book is the importance and richness of your drawings, which are used for the covers of the publication’s several different booklets. The drawings have multiple meanings: you use drawing both to plan works and as works in themselves, and all the degrees between.

GPFor me, drawing is a way to organize ideas, to try to understand them. Maybe you start with an idea, a suggestion, and you clarify it through drawing, or through writing.

PMFYes, when you and I have worked together I’ve often seen you want to sit down and write about how to tackle a certain project. You’ve really needed to do that.

GPYes, it’s a way of schematizing and clarifying the points between thoughts. Thoughts accumulate and overlap, there can be so many aspects, but through drawing, through writing, you can collect them in a synthesis.

CBWritten language has always been important to you.

GPYes, but I don’t write for the writing itself, I write to clarify ideas.

CBThe pencil itself, as wood and graphite, plant and mineral, is tied to the materiality of your work; the pencil’s materiality is tied to the work’s materiality. For you, I think, writing is a material.

GPYes, somewhat. Writing has a particular identity at a particular moment. The drawing, meanwhile, is an expressive form that can be understood independently of the specificity of language—a drawing can be understood by a Japanese person, an African, a European, more or less in the same way, it has this universality. I think its permanence in time is its most interesting characteristic. We have drawings from 30,000 years ago and we still more or less understand their meaning; but we can’t understand writing from 30,000 years ago. That immediacy, that capacity, sometimes, to recognize even the feelings in a drawing is an extraordinary quality, a sort of universality—perhaps only music comes close to it. So drawing is very important to me, and opening each booklet with a drawing seems to me to be a wonderful way to show the medium’s importance in the development of the work.

PMF How is it possible to condense an entire career or a body of work within a single book?

CBI believe that the book’s importance lies in our intention to do precisely that, even if we know it is not entirely possible. What we can say or do at this particular moment is try to bring that moment fully to bear on the work. That I think is the greatest ambition—that and the hope that some of the things found in the book will prove useful in the future.

GPAbove all, it has to be an object that we want to make, that doesn’t bore us. That’s the only way to avoid boring the reader as well.

Artwork © Giuseppe Penone. Photos: Angela Moore, except booklet drawings © Archivio Penone and © Ellen Page Wilson. Conversation translated from the Italian by Marguerite Shore