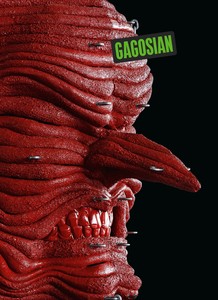

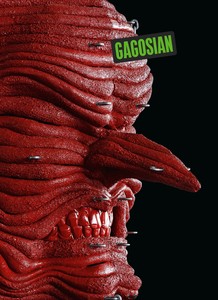

Now available

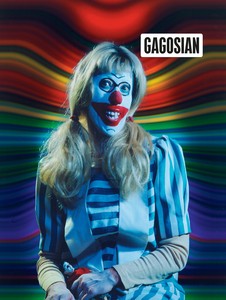

Gagosian Quarterly Fall 2022

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

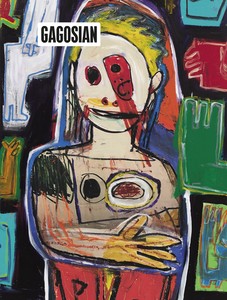

Winter 2018 Issue

One year after the opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, Jean Nouvel and Giuseppe Penone sat down with Alain Fleischer, Pepi Marchetti Franchi, and Hala Wardé to reflect on how the museum and Penone’s commissioned artworks for the space came to be.

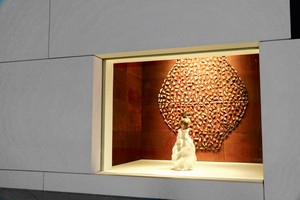

The geometric-patterned dome of the Louvre Abu Dhabi © Louvre Abu Dhabi. Architect: Jean Nouvel. Photo: Roland Halbe

The geometric-patterned dome of the Louvre Abu Dhabi © Louvre Abu Dhabi. Architect: Jean Nouvel. Photo: Roland Halbe

On November 8, 2017, Emmanuel Macron, president of France, and Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum of Abu Dhabi unveiled the magnificent Louvre Abu Dhabi, designed by Pritzker Prize–winning architect Jean Nouvel. Ten years in the making, the museum’s extraordinary design has won accolades worldwide—it was hailed “a galactic Arabic wonder” and an “utterly original blockbuster building” by the New York Times and the Financial Times alone. The structure comprises a mesmerizing 490-foot-wide geometric-patterned dome, which filters sunlight to create what’s been called “a rain of light” on the medina of fifty-five individual but connected buildings arranged below, including the museum’s gallery spaces. A universal museum for the Arab world, the institution, according to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, aims to focus on “stories of human creativity that transcend individual cultures or civilization.”

Penone is one of two contemporary artists, the other being Jenny Holzer, who were invited to respond to the building and its mission with a site-specific permanent commission. Titled Germination, Penone’s three-part installation takes center stage under the museum’s dome, creating a subtle yet powerful dialogue with the surrounding architecture and the landscape beyond it.

We recently sat down with Penone and Nouvel to discuss the extraordinary experience the building offers. Over toasted almonds and raspberries at Nouvel’s home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, followed by a hearty lunch at the legendary Colombe d’Or across the street, we learned about the opportunities and challenges presented by this unprecedented endeavor. We were joined by Hala Wardé, Nouvel’s partner on the project, and the film director Alain Fleischer, who is currently producing a documentary on the museum.

—Pepi Marchetti Franchi

ALAIN FLEISCHER How did this project begin?

Giuseppe Penone Well, when I first came to Jean’s studio in Paris, in June of 2014, I’d been contacted about the project by the Louvre, and I’d seen images of it in the press, but that visit was the first time I saw the maquette. What really struck me was that it had a hole so you could get your head into the interior—it was a great idea to see the space on that scale.

Jean Nouvel Yes. . . . But you did have to crawl on all fours to get in!

GP Yes, but putting your head into the space gave you a way to understand it, it gave you the feeling. Afterward I was asked to propose works for two windowlike vitrines built into the walls, one opposite the other, in a collaboration with la Manufacture nationale de Sèvres. But looking at the maquette and at the drawings, I thought there’d be an opportunity to propose a third work, the bronze tree, to connect the ideas in the two vitrines.

JN We need to make clear, though, that on this project I’d asked at the start to have artists working with me. When I say with me, I mean with the architecture: I wanted their work to be completely and permanently integrated into the building. I always say that architecture is the mother of the arts, it’s there to welcome artists in. Beyond the fact that architects are artists, they’re also the welcomers, and they have a role as coordinators, determining a hierarchy among spaces and among the meanings of those spaces for their occupants. I wanted the building to be marked in two ways: once in its flesh, in its walls—and for that I immediately thought of Jenny Holzer, as an artist of inscription—but I also wanted works that were architectural in scale, that would mark the main public spaces and would relate to the elements. Because that’s what there was on the site—sky, sea, and sand—along with a long history of earlier life.

That was what I thought of you for: I wanted someone who could do something with the space in full awareness of the elements. You had a lot of freedom and you used it. I was delighted, of course, to have the tree in the middle, given that the tree calls for meditation on the vault of the heavens, it seems to me, or in any case on its symbol, the building’s dome, since architecturally a dome is always a symbol of the sky. So you were working with a sort of theoretical infinite as your horizon, because even while a dome is finite, it evokes the universe. That must have been difficult, since your work had to confront the building without clashing with it. The tree manages that perfectly, and it also talks about history.

GP When I first went to see the building, my immediate reaction was that it married perfectly with the idea of the sand dune. There was probably a scattering of sand dust on the dome.

JN I prefer it like that.

GP It’s incredible. And there’s this feeling of something floating in space, but what I found extraordinary was that architecture archetypally is the thing that protects those inside it, shielding them from the sun and the elements, and it’s this primordial function of architecture that your building epitomizes. That was my first thought, and my second had to do with the way the dome fragments light, this extraordinary rain of light in the interior. It was in response to that idea, embodied in the architecture, that I came up with the tree. I chose a tree with a structure of branches going off in all directions, and I set mirror elements in different places to index certain aspects of the architecture. Usually when I do something for a place, even just for a temporary exhibition, I try not to create a contrast with the space and the view but instead to engage them in dialogue, to create a synergy. There’s no point making something that competes.

Louvre Abu Dhabi roof plan with dome. © Architect: Jean Nouvel

JN It became clear to us very quickly that the tree and its branches would link directly to the dome. And looking at it now, it seems, amazingly, to be readable in two ways, both as the tree ascending and as if a fragment of the dome were descending, like a kind of petrified bronze lightning coming down to the ground. And at the top of the tree, the edge between tree and dome can be very difficult to pick out, depending on the time of day.

GP Exactly.

JN Obviously the mirrors complicate that again, because they introduce a geometrical element that relates to the apertures in the dome. So there’s an osmotic quality that at the same time effects a kind of dematerialization. All that is symbolic—in fact, if you agree that a dome symbolizes the cosmos, it’s obviously ultra-symbolic. And when you have the branches connecting these elements in these two different ways, and becoming increasingly polysemic, you look at that and you see there’s a relationship, but what’s up there and what’s down here? What is that relationship? Does the tree touch the dome or does it not? Why is there a tree here in the first place? Why is it bronze? All these questions get mixed up together.

GP It connects earth and heaven.

Giuseppe Penone, Jean Nouvel, and Hala Wardé reviewing the model for the Louvre Abu Dhabi, 2014. © Photo: HW architecture

Jean Nouvel and Giuseppe Penone pictured with Leaves of Light during the museum’s construction, 2017. © Photo: HW architecture

JN Trees generally have an osmotic relationship to the sky: they always let some of the sky through, so they seem to be dissolving into the sky.

GP The other aspect was the earth. I didn’t want to have the tree springing out of the floor, that would have felt very unnatural. So I thought of enlarging a handful of earth. It’s like a base that isn’t a base, which relates to and completes the idea of the tree.

JN It symbolizes the earth, and it’s one more mystery.

GP As a form, it’s not immediately legible. You only understand it later.

JN I don’t know if you ever understand it, but you don’t have to. The tree emerges out of something, whether it’s a rock or what you don’t know, but it rises up in a totally abnormal way. Yet the question of anchoring, of rooting, is solved, because if you’d had a slender trunk going into the floor, that would have been bizarre.

GP The entire installation comprises three individual works under the overall title Germinazione [Germination]: the bronze tree sculpture; a vitrine with a terra-cotta vase; and another vitrine in which, on a porcelain wall, there’s a drawing developed out of the thumbprint of Sheikh Zayed, founding father of the United Arab Emirates. The tree establishes a dialogue with the space and its architecture, while the two vitrines connect with the museum’s mission and region.

I’d been told about the idea that the museum should be a museum of global culture, and that’s what prompted me to create a work with handfuls of earth from all over the world. Earth has memory, a memory of the animal, mineral, and vegetable life of the place it comes from. Another concern I had was to relate the work to the reality of the country; there isn’t a pictorial tradition in that culture but there’s a tradition of pottery, a tradition of ordinary, useful objects. Vases are found in every culture, and the shape is anthropomorphic, stemming from the human body. So in one of the vitrines I created a vase shaped like the profile of a pregnant woman. It’s made out of clay found in various parts of the world, and on the wall behind it I’ve drawn its shape again, using pigments from different regions of the world. In the other vitrine is the drawing Propagazione (Propagation), made at Sèvres on a porcelain wall and developed out of the thumbprint of Sheikh Zayed.

JN That was a wonderful idea, to get clays from different parts of the world. They have different textures, different colors, and there’s a symbolism there as well.

GP The idea of placing a fingerprint, of introducing touch, the fingerprint of Sheikh Zayed, who has an almost holy status, so that would help tie the work to that particular place. Toward the end of his life, the sheikh couldn’t write his signature any more, so he used a fingerprint. And I got a photo of that print.

Hala Wardé A very poor photo.

GP A very poor photo, and I had to interpret it somewhat for the lines, but after a long struggle to get it, at least I had a basis I could work on. Afterwards, I redid that drawing so it corresponded to every line in Sheikh Zayed’s thumbprint.

JN The work is so symbolic of the country’s identity, it’s wonderful. It’s exactly what was needed—to mark a building with a permanent work, it has to include messages of basic importance, things that anchor the building. If architecture is to relate to its context, it must include elements that couldn’t be moved anywhere else. In any particular place, I always try to do things you can’t do anywhere else. Obviously these things have to be specific to each case, and in Abu Dhabi everything works in relationship to the dome. Everything is symbolic of the country, its topography, its earth, its trees. And all this work with the light and with the ground leads to art that’s different in kind from the objects displayed as part of the collection, because a collection changes over time. So you have two categories of work in the museum, one integrated with the architecture and part of the place forever, and one in the collection and capable of wandering off from time to time, coming back, even disappearing.

Exterior view of Louvre Abu Dhabi. © Louvre Abu Dhabi. Architect: Jean Nouvel. Photo: Roland Halbe

GP Unlike the works in the collection, the works that are integrated with the architecture are also necessarily contemporary with it.

JN Yes, they testify to the moment. They testify to the relationship between the architecture of the time and the art of the time.

GP Which is not the same as a curator’s choice of contemporary works for the collection. Personally I’m happier to have my work integrated into the architecture than to have it just join the collection.

AF Giuseppe, you’ve done very beautiful works where you’ve marked the surface of water through the effects of something other than light.

GP It’s bubbles of air.

JN I’ve always wanted to inscribe something in water.

GP You mentioned that to me when we first met, and I said that I preferred a drawing on water, and in fact I’ve done a work like that: there’s a surface in the pool with holes in it, and air bubbles rise up from it and create a drawing on the surface of the water. The piece appears and disappears, a bit like breathing: you see the bubbles trouble the water surface for five or ten seconds and then disappear. I’ve done that at Venaria, a palazzo near Turin. It works even in the cold because compressed air is warmer than the water, and stops it from forming ice.

AF What leads you to an artist for a particular building? You don’t always do that.

JN No, but it’s always a question. First of all it’s a question for the client: we often make a proposal, but the art is the first thing to go. Many projects never get started. After that, of course, we have to find out whether the artist is interested. And then, for a long time now I’ve been deeply troubled by France’s 1-percent principle [the obligation to spend 1 percent of the cost of a public building project on art]—it makes for little things that come in after the rest, have no relationship to the place, and take up a lot of time. And the procedures for choosing the artists, and the places where the art will go—it’s a bureaucratic process, and that’s not how art should get into a building. I think the artist is a maître d’oeuvre in the same way the architect is, and the art is a significant part of the building. That was how it was in earlier eras with artists and craftspeople: just look at our civilization’s religious art, sculpted tympana, carved capitals, stained-glass windows, wrought iron, painted ceramics—they’re completely inseparable.

Giuseppe Penone, Leaves of Light – Tree, 2016, bronze and stainless steel, 689 × 472 ½ × 472 ½ inches (17.5 × 12 × 12 m). Architect: Jean Nouvel. Photo: Roland Halbe © Louvre Abu Dhabi

GP There wasn’t a distinction between the different domains.

JN You might think the abstraction of modern architecture would have helped it to integrate art, but exactly the opposite has happened. Paintings and tapestries go up on the walls, sculptures punctuate corners, but it’s rare to find a really osmotic relationship.

GP Very few architects really think about art.

JN Yes, and when you think about the entire history of architecture, that’s incredible. Something’s gone wrong.

AF Jean, can you imagine creating art for your buildings yourself? You originally wanted to be an artist.

JN Yes, I wanted to be an artist, but I soon realized I could do something with architecture, and in the end there’s not that much of a difference. It’s what suited me, really.

GP In the past there were sculptors who were also architects, such as Bernini and Michelangelo. There was a continuous dialogue between these different possibilities. It’s only recently that you see a specificity to each form of expression. The difference is, architecture has a responsibility and function of providing habitable space—it’s practical—while art is generally free from the need to be available for use, unless it falls into being decor.

JN Something that’s changed a lot in the contemporary period is that artists now claim absolute autonomy—in the age of the white cube, they’ve wanted to be alone in the world—and with a commissioned work you can’t do exactly what you want. But many masterpiece Renaissance paintings were commissions, and the commissions of tough clients who had clear and constraining demands. I think it’s important to bring back the idea of integration: the artist shouldn’t be all alone in the world. And accepting commissions doesn’t stop you from doing what you want elsewhere, in freestanding works for museums and collectors. It’s absolutely necessary for artists to return to the kind of permanence involved in giving a place its character. Because a place that gets its character through art has another advantage: it will have that character forever, and if you want to see it you have to go there, it will never move elsewhere. It represents a complete recharacterization of a city, a neighborhood, a building, a garden, whatever. Art really has to get back into everyday life.

GP In my work, if an exhibition is to be a good exhibition and it’s outdoors, whether it’s there for two weeks or three months, it has to look as if it’s there forever. That’s the only thing that allows the work to be. Otherwise it’s just something that’s been put there, that has no roots. So when we began our collaboration I was comfortable with it, because I’m in the habit of thinking about the place and the work together. The work has to be integrated into the space, has to form part of the space. Otherwise it becomes decor, something you can put somewhere and move around. That kind of independence of art from reality is rarely right for my work.

Giuseppe Penone, Earth of the World – Vase, 2016, terra-cotta and porcelain, vase: 18 ⅛ × 12 ¼ × 12 ¼ inches (46 × 31 × 31 cm); base: 45 ¼ × 30 × 21 ⅝ inches (115 × 76 × 55 cm). Photo: Greg Garay

JN Museums sometimes accentuate that when they uproot art, taking religious works, say, and removing them from their original conditions, losing the effects of light, scale, materials, and place. Those works suffer an amputation—they’re seen and interpreted in a context in which they can no longer be felt.

AF Did the two of you talk a lot before deciding what to do?

JN Not a lot, no, but as much as we needed to. It was important to me to explain the building to Giuseppe, to tell him about my thinking, and for him to understand what he had the right to do.

GP At one point they told me the tree was too big, that I’d have to make it smaller. There were a few restrictions like that.

JN And of course everyone wanted their say. That’s democracy—but art and democracy don’t always go together very well. You have to see what’s legitimate in those terms; people have to understand that the artist is there to create a place, a place for everyone, for the whole society. Artists are generous in their philosophy: they’re there to enrich, they’re there to testify, they’re there to do the very best they can. That’s how you create something that’s a testimony to its time. It’s not something you can do piecemeal.

AF You choose artists in terms of what you know about their work, obviously, but when you invite them to participate in a project, are you specific in what you ask for? Do you know what you want?

JN I’m not very specific. I’m specific about my thinking on what it means to have a work permanently integrated with the architecture, but once that basis is established, I always hope to be surprised. I’m not at all someone who says, You’ve got to do this, you’ve got to do that. On the other hand, I also know what I don’t want, which is a clash. It’s easy for an artwork to destroy a space.

Earth of the World – Vase, with Giuseppe Penone’s Earth of the World – Clay Lumps, 2016, terra-cotta and iron, 237 ⅜ × 177 ⅝ × 11 ⅞ inches (603 × 451 × 30 cm). Photo: Greg Garay

GP In my case the whole thing started with the vitrines.

JN Yes, that was the Trojan horse.

GP The vitrines in a space like that offer endless possibilities, there were a lot of things I could have done. There’s really no such thing as a good space or a bad space; some are certainly better than others, but in principle, if you can integrate the piece with the environment, it works. If you have a really high-quality space, it will work that much better, but even in a very ordinary space, if the piece has a real, honest relationship to it, it will work.

AF Jean, have you ever changed a space to adjust it to an artist’s proposal?

JN Oh yes, I’m ready to do that. I just have to be convinced. If it’s suggested that I alter a space for an artwork, I often have no problem with that at all, I see it as a way of developing the architecture. And I enjoy working with artists as professionals who have something to say when considering architectural or spatial features in depth. When you work in greater depth on certain parts, it really shows—those areas become loci of crystallization, they become expressive.

AF Giuseppe, is it very different for you to work with an architect rather than a collector?

GP It’s unusual for me to get a commission from a collector; my collectors generally buy something they’ve seen, the work is already made. And then, when I can, I go see how it ought to be installed, to make sure it’s properly received. With architects, though, you make a proposal. The proposal becomes a project, and a project is complex. A young architect’s main concern is to get work built; only if it’s built will later commissions open up. So there’s often a level of dependence, the architect isn’t completely in control. In painting or sculpture, on the other hand, you can do something completely personal and autonomous. Maybe a commission will follow, but the approach is very different. The difficulty of making great architecture is that it’s dependent on a commission, which the making of a sculpture is not.

JN That’s also a matter of collaboration, of shared ambition.

GP Yes, of course, but it can be difficult for someone to imagine a work. The architect, the sculptor, the artist, may be able to see it in their minds, but it can be hard to make others understand it. I’ve found that people often prefer a rendering done on a computer to a great drawing, because they don’t necessarily know how to read a drawing.

JN They’re not always attuned to feeling, essentially. They want to understand, and understanding is useful, but the crucial thing is feeling.

Giuseppe Penone, Propagation, 2016, drawing on porcelain, 141 ¾ × 165 ⅜ × 4 inches (360 × 420 × 10 cm)

AF Jean, would you say that most of today’s best new buildings are related to culture, to art: museums, opera houses, concert halls?

JN I don’t think that’s true.

AF Can you give me examples of remarkable buildings that aren’t cultural centers?

JN Religious spaces continue to inspire. And there’s plenty of bad architecture in the museum and gallery world. I think the commissioners in that world, though, are often more accepting, more ready to allow certain freedoms. They’re often open to a building that stands out, that’s iconic—in fact that’s often what they’re after. And that can lead to the production of more-heroic architecture. Though that’s certainly not always the case.

Peter Zumthor’s thermal baths in Vals aren’t a museum, and they’re a contemporary masterpiece. His chapel, too.

GP Let’s not forget that museums are cultural institutions, intended to communicate, to disseminate, so the buildings are often better known than others.

JN Yes, that’s true. But the program of a museum puts many constraints on the interior. I think a lot of museum buildings follow an ethos of “Look beautiful and keep your mouth shut!,” which isn’t exactly architecture’s role.

GP I want to ask about moral rights, because the integrity of an artist’s work has to be respected and there are generally accepted rules. You can’t alter a painting.

JN I’m in favor of buildings changing and developing; it’s simply a question of realizing that there are different ways of doing it and getting it right. There has to be respect for the integrity of the original work, whether it’s art or architecture—it’s as simple as that.

Pepi Marchetti Franchi The Louvre Abu Dhabi is a truly extraordinary building and an extraordinary collaboration. It’s a unique example of an important European museum opening an exhibition space in the heart of the Arab world. Did that context play a role when you were developing the project? Or is it perhaps, Giuseppe, the same to you as doing a piece someplace more ordinary?

GP Obviously doing a work in the Emirates now gets a lot of attention. The same thing done elsewhere would attract less interest.

PMF Do you find it critical to know about the tradition and the region? Or not?

GP Of course you immerse yourself, you learn, but you don’t have to live in a country to make work there.

Giuseppe Penone, Propagation, 2016, drawing on porcelain, 141 ¾ × 165 ⅜ × 4 inches (360 × 420 × 10 cm)

PMF And you, Jean?

JN Well, you’re always somewhere, and you have to reveal that somewhere, you have to get deeper into that somewhere. So, depending on where that somewhere is, your response will differ. To me, buildings aren’t interchangeable, they have roots, they have reasons for being that go very, very deep. And probably in a situation like Abu Dhabi, given the comparative roles of culture and religion there, to show different forms of thought over the ages, and to show that things are different, and extraordinary, in other places, takes on a very political significance. A museum like this one may have been more keenly awaited there than elsewhere because it’s in a situation where it’s meant to present a universal art. We’re also expected to prove that the creation of a total work of art is possible in the prevailing historical, geographical, and political conditions there.

HW Giuseppe, when we were in Abu Dhabi and the tree was being installed, there was a pretty extraordinary moment as it was getting more and more upright, and then suddenly it was completely absorbed by the dome. I felt there was something at that moment that you hadn’t anticipated.

GP That’s true. I’d seen the work against the sky, but when we were there, it fused with the ribs of the dome, and that surprised me to some degree.

AF You had a little adventure together, you and Hala: you chose this tree from among all the other trees.

GP Yes, we did. There was a problem of size, there was a problem of form, and I had three possibilities of trees that for various reasons had to be cut down: one possibility was a very beautiful tree, but it didn’t work from a budgetary point of view. There was another tree that I thought might work, but then we found this third tree, which was bigger but there was a place where it was missing a branch. I added that back in later, and reworked the overall shape, but at that point I still wasn’t sure. Then I was concerned that it shouldn’t come too close to the skin of the building, that was another worry. But we did it, with Hala, and we made the right choice.

PMF Where did you find it?

GP In my woods in San Raffaele, near Turin.

HW There’d been a lot of discussion to get to that point, because in fact, when you saw the dome, the idea came to you right away.

PMF You’d seen the dome in a drawing at that point, but not the real dome.

HW It didn’t exist yet, but when you saw the site you could imagine it.

GP When I was first there I couldn’t see the dome, but I could see the scale of the architecture.

PMF Were the buildings up?

HW Yes, the buildings were up but the dome was still under construction.

GP I was surprised that Jean agreed to have the work where it is, almost in the middle of the dome.

HW But Jean was very keen on that idea. It’s true there were people who wanted to decide on the locations for the permanent works; we had to explain that it was the artists who had to choose.

GP For the vitrines there was no choice, but I suggested doing the third work.

HW The tree, which was installed in the center. It’s become a meeting point, you hear everyone on their phones: “Where are you?” “I’m by the Penone tree.”

All artworks by Giuseppe Penone © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Interview translated from French by Dafydd Roberts

Since studying literature, linguistics, and anthropology, Alain Fleischer has taught in a number of universities and in film, photography, and art schools in France and abroad. A laureate of the Académie de France in Rome, Fleischer created Le Fresnoy–Studio national des arts contemporains, serving as the institution’s director since 1997 on assignment for the French ministry of culture.

Founding director of Gagosian Rome, Pepi Marchetti Franchi has overseen more than forty exhibitions at the gallery since it was established, in 2007. Raised in Rome, she spent many years living in New York, including the eight years she was working at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: Andy Massaccesi, courtesy Mutina

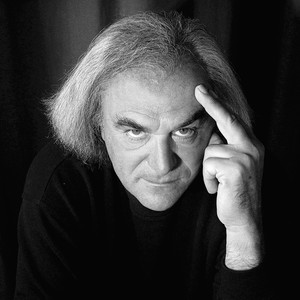

Jean Nouvel is a key protagonist of intellectual debate in France regarding architecture, and was a founding member of Mars 1976 and Syndicat de l’Architecture. First assistant to the architect Claude Parent and inspired by urban planner and essayist Paul Virilio, he started his first architecture practice in 1970. Nouvel’s strong stances and somewhat provocative opinions on contemporary architecture in the urban context, together with his unfailing ability to inject originality into all the projects he undertakes, have formed his international image. Photo: Katarina Premfors/The New York Times/Redux

In an oeuvre spanning almost fifty years, Giuseppe Penone has explored the subtle levels of interplay between humans, nature, and art. His work represents a poetic expansion of Arte Povera’s radical break with conventional mediums, emphasizing the involuntary processes of respiration, growth, and aging that are common to both human beings and trees, with which he is so deeply involved. His works can be found in many major museum collections around the world.

Hala Wardé is the founding architect of HW architecture. Long-term partner of Jean Nouvel, Wardé led the Louvre Abu Dhabi project and the One New Change development in London. In 2016, HW architecture won the architectural competition for the Beirut Museum of Art, the future landmark museum in Lebanon.

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

Le Couvent Sainte-Marie de La Tourette, in Éveux, France, is both an active Dominican priory and the last building designed by Le Corbusier. As a result, the priory, completed in 1961, is a center both religious and architectural, a site of spiritual significance and a magnetic draw for artists, writers, architects, and others. This fall, at the invitation of Frère Marc Chauveau, Giuseppe Penone will be exhibiting a selection of existing sculptures at La Tourette alongside new work directly inspired by the context and materials of the building. Here, Penone and Frère Chauveau discuss the power and peculiarities of the space, as well as the artwork that will be exhibited there.

As spring approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, Sydney Stutterheim reflects on the iconography and symbolism of the season in art both past and present.

Elizabeth Mangini writes on Giuseppe Penone’s installation of two sculptures at San Francisco’s Fort Mason.

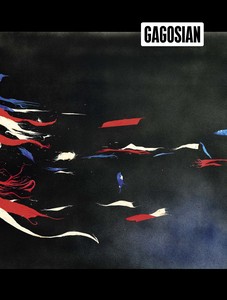

The Spring 2020 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #412 (2003) on its cover.

An outdoor installation by Giuseppe Penone in San Francisco’s historic Fort Mason features two life-size bronze sculptures cast from fallen trees. The project continues the artist’s long investigation of the perpetual give-and-take between humans and nature. In this video, Penone discusses what drew him to this landscape and the concepts behind the installation.

Gagosian director Pepi Marchetti Franchi speaks about Giuseppe Penone’s recent exhibition in San Francisco, detailing the various works and their relationships to the artist’s long-standing sculptural practice.

Jenny Saville reveals the process behind her new self-portrait, painted in response to Rembrandt’s masterpiece Self-Portrait with Two Circles.

Giuseppe Penone discusses his new monograph, The Inner Life of Forms, with the book’s editor Carlos Basualdo, senior curator of contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, at the Greene Space, New York. Hosted by art critic Deborah Solomon.

The Winter 2018 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available. Our cover this issue comes from High Times, a new body of work by Richard Prince.

In the small skiing village of Gstaad, among the towering mountains of the Swiss Alps, lies a surprising and ambitious exhibition of sculpture by Giuseppe Penone. Susan Ellicott tells the story of how this installation came to be.

The Spring 2018 Gagosian Quarterly with a cover by Ed Ruscha is now available for order.