Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Fall 2022

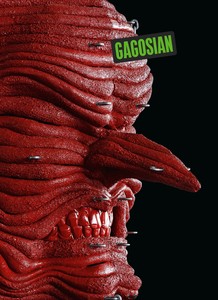

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

Spring 2020 Issue

Elizabeth Mangini writes on Giuseppe Penone’s installation of two sculptures at San Francisco’s Fort Mason.

Giuseppe Penone, Idee di pietra (Ideas of Stone), 2004, installation view, Fort Mason, San Francisco, 2019–21

Giuseppe Penone, Idee di pietra (Ideas of Stone), 2004, installation view, Fort Mason, San Francisco, 2019–21

In Rotterdam a large tree hovers preternaturally three feet above the ground, in Münster a fallen trunk becomes the conduit for a spring, while in Rome architectural fragments seem precariously lodged in a tree’s high branches. Walking among Giuseppe Penone’s outdoor sculptures, one has the sense of being in a landscape at once surreal and surprisingly natural. With an installation at Fort Mason, a former military site now part of Golden Gate National Recreation Area, San Francisco joins a select group of international cities to host the artist’s bronze tree sculptures. Penone’s public works, which illuminate the correlations between organic forms and their environment, have graced the grounds of such storied landscapes as the royal gardens at Versailles, the Boboli Gardens/Forte Belvedere in Florence, and New York’s Madison Square Park. Several are on permanent display in such cities as Paris, Rome, and Abu Dhabi.

Emerging as an artist in Turin in the late 1960s, Penone was first associated with Arte Povera, a critical and curatorial conceit that recognized a penchant for experience over representation among emerging Italian artists. Along with these peers, Penone’s works were included in landmark exhibitions, from Venice to Kassel and from Amsterdam to Tokyo. Penone’s persistence in working with organic forms has also led critics to link him with the Land and environmental art movements that were emerging in the late 1960s, but his material and conceptual commitment to sculpture often exceeds the boundaries of stylistic terminologies. Through five decades of making and exhibiting art around the globe, Penone has become one of the most recognized Italian artists of the postwar era by probing the place of human activity in the natural world.

In Alpi Marittime (Maritime Alps, 1968), one of his earliest works, Penone measured the effect of his touch on young trees in the woods of the Maritime Alps, making long-term sculptural interventions that he documented in photographs. The most succinct of these was a metal cast of his hand that he attached to a young sapling, which grew around it. Penone later became known for carving industrial wood planks so as partly to recover the organic forms of the trees from which they had been milled. In these Alberi (Trees, 1969–), a reversal of human intervention introduced new perspectives on the “lived” experience of organic materials over time. The large-scale bronze works that Penone began to make in the 1980s are rooted in such investigations, bringing conceptual and material criticality to the ancient traditions of sculpture as public monument.

Most radically, the forms and materials of these works have the potential to shift one’s perception of time itself.

The two works installed in San Francisco are La logica del vegetale (The Logic of the Vegetal, 2012) and Idee di pietra (Ideas of Stone, 2004). Together they exemplify central tenets of Penone’s art, offering a glimpse of the breadth of a half-century of production. Penone’s large-scale public installations provide an incisive view of his career-long investigation of the role of the artist in society. His conceptual engagement with the site also allows a focus on the complex histories of land use. Most radically, the forms and materials of these works have the potential to shift one’s perception of time itself.

Idee di pietra is a towering bronze tree that lofts several large river stones high in its bare branches. This striking combination of materials and forms inspires awe as well as trepidation. The weathering bronze mimics the trunk from which it was cast so well that this carefully engineered sculpture presents itself as natural. The vertical assemblage appears to be the monumental result of a decades-long struggle between gravity and photosynthesis—opposing forces here held in tension—in contrast to boulders that the artist has installed on the ground nearby. The installation asks us to reflect on the form-giving relationships between organisms and their environment.

In a recent interview, Penone remarked that trees in nature perfectly model the work of the sculptor, since they conserve experience in their very structures. A tree’s size, the condition of its bark, the thrust of each branch, all testify to its interactions with its environment. At Fort Mason, Penone’s sculptural trees are installed on the grounds of the Great Meadow, among Monterey cypresses, sequoias, and other species both native to the region and introduced to it by California’s many waves of immigrants. The integration of Penone’s bronzes among these live specimens creates an intensified experience of both nature and art, prompting us to consider the complexity of the earth’s ecosystem and the role humans play in it.

Giuseppe Penone, La logica del vegetale (The Logic of the Vegetal), 2012, installation view, Fort Mason, San Francisco, 2019–21

La logica del vegetale further reinforces the interconnectedness of organic life. Here a twisting bronze trunk sprawls horizontally across the meadow. Its massive upended root ball presents a visually arresting tangle of bronze forms. Meanwhile, the branches of this seemingly felled tree recede into the distance, like five fingers at the end of an outstretched arm. At the tips of these bronze branches five living trees rise vertically, all native varietals planted by the artist (valley oak, coast live oak, California bay laurel, and bigleaf maple). Emulating the way decomposing matter reaches beyond itself to provide for the survival of other organisms, the work underscores the interdependencies inherent to our existence.

Works such as La logica del vegetale are at their rhetorical best in long-term or permanent installations that give their live elements a chance to grow. Albero delle vocali (Vowel Tree), a similarly recumbent bronze trunk, has been installed in the gardens of the Tuileries in Paris since 1999, allowing visitors to witness a changing dynamic between the sculpture and the landscape. The five live trees planted at the ends of that tree’s bronze branches have matured over two decades, while vines and other flora camouflage the artifice of the sculpture’s root end. Allowed to stay in place for decades, the work becomes slyly subversive, inserting a large, apparently dead tree trunk into a meticulously manicured Baroque garden. Similar permanent installations of Penone’s take root in Kassel, Maastricht, and Turin. Presenting the evolution of forms, structures, and materials over time, such works index the ways in which even the smallest human actions impact the material world.

Penone’s works often allow us to set our own, corporeal sense of time against the more extended lifespan of a tree, a stone, and ultimately the earth itself.

Indeed, Penone’s outdoor sculptures spark the recognition that the landscapes and parks in which they are installed are not really “natural” at all. Instead, they are palimpsests of human occupation, intervention, exertion, and sculpting of the earth. The area that is today Fort Mason was once part of the homeland of the Ohlone people. In the eighteenth century Spanish settlers recognized the strategic value of the site, overlooking the sole access from the Pacific Ocean into San Francisco Bay, and founded a military battery there in 1797. Over the ensuing two centuries, the land passed under Mexican control (1822), was seized by American rebels (1846), and by the time of the Civil War had become an upscale neighborhood. The site of relief camps after the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, it was an important embarkation point for US troops heading to the Pacific during World War II, all before becoming part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area in 1972.

In terms of human activity, struggle, and development, the 250 years since the late eighteenth century constitute a long time. That period encompasses all of the US presidents, more than fifteen family generations, countless wars and battles, endless building campaigns, the invention and obsolescence of many technologies, the identification and development of cures for a good number of diseases, and so on. Two hundred and fifty years, though, may be a small part of a tree’s life. Several species can live over one thousand years, and California’s prized sequoias (Sequoiadendron giganteum) can survive for more than three thousand. Penone’s works often allow us to set our own, corporeal sense of time against the more extended lifespan of a tree, a stone, and ultimately the earth itself. Gauged by such yardsticks, a political cycle, a human lifespan, or even the longer life of a particular culture seems remarkably brief. Occupying their intersection of sculpture and vegetation, Penone’s public works bring the profound aspects of organic life into focus.

Given this network of concerns, it comes as something of a surprise that it has taken so long for any of Penone’s monumental trees to go on public view in Northern California, whose residents consider themselves at the forefront of progressive environmentalism. But like Idee di pietra, the Bay Area is marked by fundamental tensions between opposing forces: social activism versus rampant, technology-driven capitalism, or the preservation of ancient forests such as Muir Woods versus the development of an increasingly ephemeral culture. Without providing solutions to such disparities and conflicts, Penone’s works at Fort Mason offer an opportunity to reflect on them, showing that the same complex interdependences exist in the natural world. Adopting the temporal perspective of nature, even for the relatively brief moment of our encounter with his sculptures, can profoundly affect our worldviews and, ultimately, hopefully, our actions.

1 See “Giuseppe Penone: Gli alberi: sculture perfette,” video interview, Rai Cultura, 2014. Available online at www.raicultura.

it/arte/articoli/2018/12/Giuseppe-Penone-gli-alberi-sculture-

perfette-1fa8f82c-f4f6-4bb2-8874-4043af51a2c5.html (accessed December 1, 2019).

Giuseppe Penone at Fort Mason, Fort Mason, San Francisco, October 24, 2019–March 28, 2021; presented by Gagosian in partnership with the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy and Golden Gate National Recreation Area through the Art in the Parks program

Artwork © Giuseppe Penone/2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris; photos: Matthew Millman

Elizabeth Mangini is an art historian and associate professor at California College of the Arts in San Francisco. Her monograph Seeing Through Closed Eyelids: Giuseppe Penone and the Nature of Sculpture is forthcoming from University of Toronto Press.

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

Le Couvent Sainte-Marie de La Tourette, in Éveux, France, is both an active Dominican priory and the last building designed by Le Corbusier. As a result, the priory, completed in 1961, is a center both religious and architectural, a site of spiritual significance and a magnetic draw for artists, writers, architects, and others. This fall, at the invitation of Frère Marc Chauveau, Giuseppe Penone will be exhibiting a selection of existing sculptures at La Tourette alongside new work directly inspired by the context and materials of the building. Here, Penone and Frère Chauveau discuss the power and peculiarities of the space, as well as the artwork that will be exhibited there.

As spring approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, Sydney Stutterheim reflects on the iconography and symbolism of the season in art both past and present.

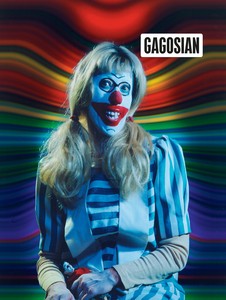

The Spring 2020 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #412 (2003) on its cover.

An outdoor installation by Giuseppe Penone in San Francisco’s historic Fort Mason features two life-size bronze sculptures cast from fallen trees. The project continues the artist’s long investigation of the perpetual give-and-take between humans and nature. In this video, Penone discusses what drew him to this landscape and the concepts behind the installation.

Gagosian director Pepi Marchetti Franchi speaks about Giuseppe Penone’s recent exhibition in San Francisco, detailing the various works and their relationships to the artist’s long-standing sculptural practice.

One year after the opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, Jean Nouvel and Giuseppe Penone sat down with Alain Fleischer, Pepi Marchetti Franchi, and Hala Wardé to reflect on how the museum and Penone’s commissioned artworks for the space came to be.

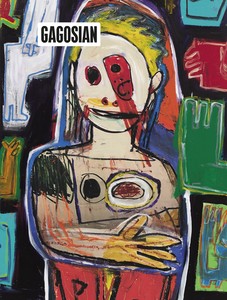

Jenny Saville reveals the process behind her new self-portrait, painted in response to Rembrandt’s masterpiece Self-Portrait with Two Circles.

Giuseppe Penone discusses his new monograph, The Inner Life of Forms, with the book’s editor Carlos Basualdo, senior curator of contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, at the Greene Space, New York. Hosted by art critic Deborah Solomon.

The Winter 2018 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available. Our cover this issue comes from High Times, a new body of work by Richard Prince.

In the small skiing village of Gstaad, among the towering mountains of the Swiss Alps, lies a surprising and ambitious exhibition of sculpture by Giuseppe Penone. Susan Ellicott tells the story of how this installation came to be.

The Spring 2018 Gagosian Quarterly with a cover by Ed Ruscha is now available for order.