Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Fall 2022

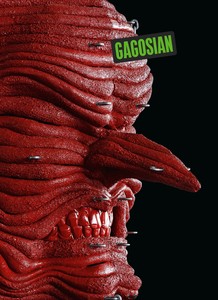

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

Fall 2022 Issue

Le Couvent Sainte-Marie de La Tourette, in Éveux, France, is both an active Dominican priory and the last building designed by Le Corbusier. As a result, the priory, completed in 1961, is a center both religious and architectural, a site of spiritual significance and a magnetic draw for artists, writers, architects, and others. This fall, at the invitation of Frère Marc Chauveau, Giuseppe Penone will be exhibiting a selection of existing sculptures at La Tourette alongside new work directly inspired by the context and materials of the building. Here, Penone and Frère Chauveau discuss the power and peculiarities of the space, as well as the artwork that will be exhibited there.

Photograph of the execution of Giuseppe Penone’s frottages in La Tourette, Éveux, France. Giuseppe Penone, Le Bois Sacré (The Sacred Forest), 2022, prepared canvas oil and wax pastel. Photo: © Archivio Penone

Photograph of the execution of Giuseppe Penone’s frottages in La Tourette, Éveux, France. Giuseppe Penone, Le Bois Sacré (The Sacred Forest), 2022, prepared canvas oil and wax pastel. Photo: © Archivio Penone

Frère Marc ChauveauGiuseppe, we’re happy to welcome you to La Tourette, where you’ve just spent four days working. But you already knew the priory, having been here about ten years ago with students from the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris, where you taught. Why are you returning here and what do you think of the place ten years later?

Giuseppe PenoneActually, this is my third visit to La Tourette because I’d already been here, at your invitation, to see the space with your brother, Bernard, several years before I brought my students. I didn’t create anything afterward; it’s a difficult space, you have to think before you do something. And the second time you invited me, I thought it could be a good experience for my students. They came to the priory and stayed for a few days, identifying places where they could make and install works related to the space. It was an extraordinary experience, of course, because it allowed them not only to conceive works but also to display them in a well-known artistic context.

FMCNow you’ve been invited to make and exhibit works here yourself. Since the priory was built by Le Corbusier, it has a special kind of architecture—unesco has classified it as a World Heritage Site—and it’s also housing for a community of ten Dominican friars. What does it mean to you to exhibit in a monastery where a community lives, works, and prays?

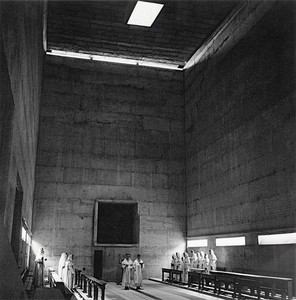

Le Couvent Sainte-Marie de La Tourette, Éveux, France. Photo: Bildarchiv Monheim GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo

GPIt’s a unique experience. This is something I’ve never done before. There was something that struck me about the architecture, and I didn’t feel completely comfortable with it at first: we see nature in the priory, but we don’t enter nature. The priory is closed in on itself. It’s like a body with eyes that can see outside, but all life is contained inside. The windows don’t open and there are very few ways to get in touch with the outside. This creates a bit of tension in the space. But the fact that there was this life, this activity, that there were people working inside a place like this—a place of meditation, a place for the spirit, for art, for prayer, for a relationship with the sublime—this interested me. It shows an openness: making a space available for this kind of activity is a great gesture of generosity on the part of the priory friars toward the visiting public and artists.

All these reflections led me to choose works for the space that I hope will be able to dialogue with it, but that also, above all, relate to imagery absent from the monastery. It’s a very austere building, with very little Christian iconography, but that iconography is present in the imaginations of the people who come here. My works present a range of subjects that may have links with Christian iconography. I’m Italian, Italy is a Catholic country, and even if you’re not a believer, you’re influenced by the iconography of religion, which comes to you through the nature of the space, through the history of the people who have lived there. Even if we don’t think about the history of the country where we were born, where we live, we’re completely impregnated by it.

FMCThe presentation of your work at La Tourette may renew people’s understanding of it. I think, for example, about the works you plan to put in the refectory, A occhi chiusi [With Closed Eyes] and Avvolgere la terra [Envelop The Earth]. They’ve been shown in exhibitions and in museums, but their placement at the back of the refectory will enrich them with a different meaning.

Giuseppe Penone, Albero in torsione sinistra (Left Twist Tree), 1988, larch wood, 328 ¾ × 15 ¾ × 10 ⅝ inches (835 × 40 × 27 cm). Photo: © Archivio Penone

GPIt will give them a different meaning because I’m drawing on a range of feelings about the rigor of the architecture combined with the spiritual purpose for which it was made. I’m thinking of installing a work linked to hands, the gestures of hands. Objects inspired by gestures that are very simple and humble and ordinary will be placed on a wooden table. There are people eating in this space, but it’s not a restaurant, it’s something else. This is the spirit I’m hoping to capture: seeing something seemingly ordinary in a different, unexpected way.

FMCCould you speak about the beam that you plan to put in the church, sculpted in the form of a tree? For us, the friars, there may be connections between the beam of the cross and the tree of life.

GPThis is a work I made in the ’80s, out of a roof beam. It’s imposing, very large, eight meters [twenty-six feet] long. I shaped it as a tree, but it has things like nails, traces of its function, embedded in it, and they give it a meaning that similar works I’ve done don’t have, because there’s a story in the wood to do with a very simple function, supporting a building. And in the space of La Tourette, it takes on another dimension and becomes a symbolic object.

FMCYes, because it’s shown in the church, in the symbolic and sacred space between the stalls and the altar.

GPA church is not a neutral space. We enter the church and we’re in a space made for a purpose, which is that of prayer, of the spirit, and of belief in divinity. It’s a space with a meditative purpose that other spaces don’t have. Here, people will observe the work more closely and see it differently.

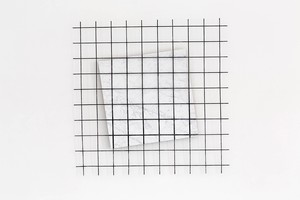

Giuseppe Penone, Corpo di pietra – rete (Body of Stone – Grid), 2018, white Carrara marble and iron, 59 × 59 × 2 ¾ inches (150 × 150 × 7 cm). Photo: © Archivio Penone

FMCYou’re exhibiting not only works that you’ve already made but works you’re creating specifically for the priory. I’m thinking, for example, of the chapter room, an important place for us that we use as a chapel in the winter. What is the work that you’ve created for this place?

GPMuch of the priory’s religious life is based on reading and recitation. Reading is done in books; there are books that are essential for the liturgy, so they’re used every day. This interests me because there’s a manipulation of the book. The book is not only an object holding words and prayers, it’s also something that we take in our hands, we touch, we turn the pages. There’s a beauty in the quality of the book itself—the binding, the paper, these elements of that kind—and also in relation to the body of the speaker, because one holds it in one’s hands. There are traces of the person’s hand on the book. This idea was the basis for the work in the chapter room, which is made of fingerprints on canvas. I tried to copy the color of a particular book, creating a kind of landscape where the fingerprints become like leaves and form a space of vegetation.

FMCAnd the book you chose from the library is a liturgical book, a Dominican missal that we use very often.

GPYou sent me photos of three books that I could use to create the work, and that was the one I liked best, because it had a kind of simplicity. Its dimensions also seemed right to me, allowing me to create a work that measures about three meters by two meters [10 by 6 1/2 feet].

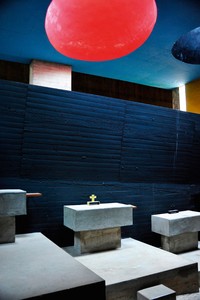

Le Couvent Sainte-Marie de La Tourette, Éveux, France. Photo: © Archives of Le Couvent de La Tourette Following spread, left: Le Couvent Sainte-Marie de La Tourette, Éveux, France. Photo: Archimago/Alamy Stock Photo

FMCYou’re also attentive to the architecture of the priory. You mentioned the rigor of Le Corbusier’s architecture, with its exposed concrete. We have walls in the priory with rough-cast casings; many architects who visit mention the “skin” of the concrete. And of course this idea of concrete skin must affect you, since it goes to the heart of your work on touch and sensation.

GPAll the concrete here was laid using planks of wood. The technique is rarely used today but it was the old method: wooden planks were assembled to make a casing and the concrete was poured inside it. Le Corbusier kept the unfinished appearance of the concrete, the imprints of every piece of wood. That gives it life. I think of each piece of wood as having the form of a tree inside it.

The building’s form can be compared to what you see in a group of trees. All the friars’ cells are framed by balconies that have small stones embedded in them, creating a vibration like the vibration of leaves. Then there are the columns, which we can think of as trunks. The whole structure that supports the floor of the building can be compared to the bases of trees. There are also roots: the crypt of the church is in contact with the earth. It’s the only part that touches the ground. All of these elements suggested to me the idea that a kind of sacred wood is embedded in the architecture of this place. From that idea I thought of doing a rubbing revealing the skin of the building. I did that using the system of sixty-three colors that Le Corbusier developed for his architecture. I had sheets made measuring 40 centimeters by 40 centimeters [15 3/4 by 15 3/4 inches], which is the size of the meditation square in each cell. Then, on sixty-three of these sheets, I did rubbings of the different parts of the building: the crypt, the church, the beams, the coatings, and the rest, following the idea of the structure of a tree.

FMCYour use of the sixty-three colors of Le Corbusier’s palette is new in your work; you usually use more natural colors, like green or ocher.

Le Couvent Sainte-Maria de La Tourette, Éveux, France. Photo: Archimago/Alamy Stock Photo

GPYes, but I don’t think it’s really that different, because I always work with existing materials. It’s not as if I created the colors to do the rubbing; I used the colors of the person who created the architecture. The palette is completely connected and coherent to the architecture.

FMCLe Corbusier built the priory on an agricultural estate. So we’re in the country; from much of the building we can see the trees of the forest surrounding us. This dialogue with nature is important—as you say, Le Corbusier was very attached to the imprint, the trace, of the wood in the unfinished concrete. This makes the building part of the brutalist trend of postwar architecture; it’s totally different from his purist architecture of the interwar period. It’s a real aesthetic choice Le Corbusier made, which you demonstrate with these rubbings.

GPFor Le Corbusier, it probably represented a freedom in relation to what he’d done before. There’s a kind of acceptance of the defects and character of the material. These surfaces aren’t soft to the touch; they’re aggressive, they have a very strong character. All of this enriched the relationship with the skin of the architecture. It demonstrates what I was trying to say before, the idea of sacred wood embedded in the materials of the priory.

FMCGiuseppe, what’s your approach to sculpture? Particularly in connection with the architecture of the priory?

Photograph of Giuseppe Penone in his studio, Turin, Italy, with Le Bois Sacré – Troncs/Piliers (The Sacred Forest – Trunks and Pillars), 2022, prepared canvas oil and wax pastel, in 24 parts, each: 15 ¾ × 15 ¾ inches (40 × 40 cm). Photo: © Archivio Penone

GPMy job has been to observe material and to reveal the forms it has. My work is an indication of form, not a creation of it. The first works I did put my body in direct relationship to a growing tree: I brought my body into contact with the tree, and the tree memorized the moment of my presence. I perpetuated this contact with a steel cast of my hand that I placed on the trunk of the tree. As the tree grew, the imprint of my hand was patterned into its flesh.

After that, I did a work in which I found the form of a tree inside an industrial beam. This was the period when there was a minimalist approach to sculpture; industrial elements were displayed as they were. I took this industrial element and found the form of a tree in it. It was one of the first works I did in 1969, and it gave me the idea of continuing to do this work, revealing the forms inside the beams, the forest inside the wood.

The same idea led me to the work in marble, revealing the veins and making sculpture from them. The veins in marble are actually layers of material inside the block. By cutting the block, we can see them as veins, as if they were the veins in our bodies. Using this idea, I made the works I call Anatomie [Anatomies, 1992–]; there are some in the exhibition here. The idea of revealing something in the material is the same principle that led me to think of architecture as sacred wood, as if there were in it an existing form, which I tried to demonstrate with the rubbing technique.

To create work based on architecture, on a single building as steeped in history, and as important for the history of architecture, as the priory of La Tourette, was a very exciting experience for me, inspiring me to create a series that encouraged—

FMCA culmination.

GPThe culmination of an idea that was present in my work but had not yet found a complete form. The series encouraged me to do that with great joy.

Giuseppe Penone à La Tourette, Convent de La Tourette, Éveux, France, September 6–December 24, 2022

Artwork by Giuseppe Penone © 2022 Giuseppe Penone/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Le Couvent Sainte-Marie de La Tourette designed by Le Corbusier © F.L.C./ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2022

Frère Marc Chauveau, Dominican and art historian, has lived for twenty years in the convent of La Tourette, built by Le Corbusier in the Lyon region of France. Since 2009, he has curated contemporary art exhibitions, inviting artists to establish a dialogue between their works and those of Le Corbusier.

In an oeuvre spanning almost fifty years, Giuseppe Penone has explored the subtle levels of interplay between humans, nature, and art. His work represents a poetic expansion of Arte Povera’s radical break with conventional mediums, emphasizing the involuntary processes of respiration, growth, and aging that are common to both human beings and trees, with which he is so deeply involved. His works can be found in many major museum collections around the world.

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

As spring approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, Sydney Stutterheim reflects on the iconography and symbolism of the season in art both past and present.

Elizabeth Mangini writes on Giuseppe Penone’s installation of two sculptures at San Francisco’s Fort Mason.

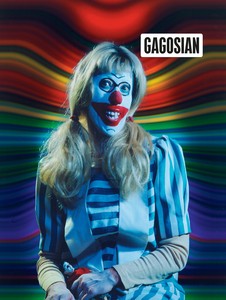

The Spring 2020 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #412 (2003) on its cover.

An outdoor installation by Giuseppe Penone in San Francisco’s historic Fort Mason features two life-size bronze sculptures cast from fallen trees. The project continues the artist’s long investigation of the perpetual give-and-take between humans and nature. In this video, Penone discusses what drew him to this landscape and the concepts behind the installation.

Gagosian director Pepi Marchetti Franchi speaks about Giuseppe Penone’s recent exhibition in San Francisco, detailing the various works and their relationships to the artist’s long-standing sculptural practice.

One year after the opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, Jean Nouvel and Giuseppe Penone sat down with Alain Fleischer, Pepi Marchetti Franchi, and Hala Wardé to reflect on how the museum and Penone’s commissioned artworks for the space came to be.

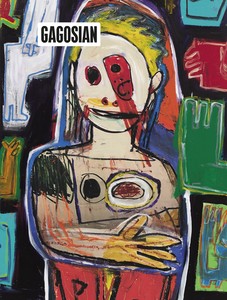

Jenny Saville reveals the process behind her new self-portrait, painted in response to Rembrandt’s masterpiece Self-Portrait with Two Circles.

Giuseppe Penone discusses his new monograph, The Inner Life of Forms, with the book’s editor Carlos Basualdo, senior curator of contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, at the Greene Space, New York. Hosted by art critic Deborah Solomon.

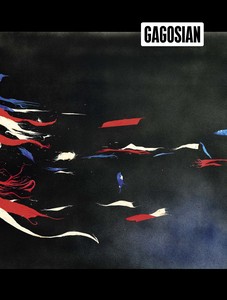

The Winter 2018 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available. Our cover this issue comes from High Times, a new body of work by Richard Prince.

In the small skiing village of Gstaad, among the towering mountains of the Swiss Alps, lies a surprising and ambitious exhibition of sculpture by Giuseppe Penone. Susan Ellicott tells the story of how this installation came to be.

The Spring 2018 Gagosian Quarterly with a cover by Ed Ruscha is now available for order.