Flags

Gillian Pistell writes on the loaded symbol of the American flag in the work of postwar and contemporary artists.

December 4, 2017

Ed Ruscha sat down with JoAnne Northrup of the Nevada Museum of Art to discuss the exhibition Unsettled, which the two co-curated. The show features a broad selection of art and artifacts spanning two thousand years by eighty artists to tell the story of the Greater West, a super-region stretching from Alaska to Patagonia, and from Australia to the American West.

Ed Ruscha, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, September 2017. Photo courtesy Nevada Museum of Art

Ed Ruscha, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, September 2017. Photo courtesy Nevada Museum of Art

JoAnne NorthrupThe Nevada Museum of Art has taken an interest in a super-region that we call the Greater West, which starts in Alaska, extends down the West Coast of the Americas to Patagonia, and over to Australia. We are interested in not just looking at our region around us, the Sierra Nevada Great Basin, but at the super-region. When you look at a map of Pangea, you can see that all those areas used to be joined, so it’s like that whole sweep of the left part of Pangea. So Pangea, reunited, that’s what we’re aiming for. And Ed Ruscha, you’ve been a resident of the west coast for quite some time.

Ed RuschaYes, for decades. I moved out west from Oklahoma City and never thought another thing about it. And that seems connected to the foundation of your idea, that people migrated west and never really looked back. I like to hike in remote areas and when I’m in the middle of nowhere and I’m hiking, I always look back over my shoulder to see where I came from, but when people migrated west, they never looked back. They just kept coming. It was a phenomenon. So here we are.

JnYes. It’s something that the director of our Center for Art and Environment, Bill Fox, calls the land of the endless horizon. People who headed west in general were looking forward and not looking back to where they came from. That’s why these people are so innovative, unorthodox, and forging a new path. That’s what the Unsettled exhibition emphasizes. The innovation and the unorthodox perspective of the artists from the Greater West. And your work is a through line in the exhibition that serves as punctuation for artists from different millennia and different areas of the greater west.

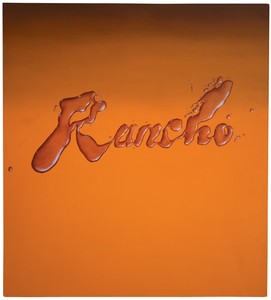

Your works often include humor. One of the works in our show is from the Romance with Liquids series. Where does this come from?

Ed Ruscha, Rancho, 1968, oil on canvas, 60 × 54 inches (152.4 × 137.2 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York

ERI have no idea where that comes from, but maybe it had to do with having pancakes for breakfast and then putting maple syrup on it and watching it ooze and goofing on that. Then wanting to make some painting out of it.

JNThere is a work by Nicholas Galanin included in the exhibition. I like to think of Nicholas Galanin as the Ruscha of the young indigenous contemporary art world [laughter]. I love how he has used language in a really arresting way, it grabs our attention. In the exhibition, it is hung near your work and I love the way that it’s sort of in conversation with your work. You and I have talked quite a bit about the indigenous artists and how they take something and make it new.

ERYes, and then I wonder, you must have had to travel far and wide to find these people. Because a lot of them live in somewhat remote locations, don’t they?

JNYes, Galanin lives in Sitka.

ERAnd still these artists are up to speed with what’s happening in the world of art today. In the development of modern art, it seemed to settle into a couple of places in the world. One location was Paris, where everybody thought that’s where the great art came from, and then New York. So all art seemed to emanate from these two places. Nowadays, there is no one place—with modern communication and people seeing everything all at once, artists are picking up on every possible avenue of expression. I’m not surprised that Nicholas is into his own thing, but it’s also riveted to the development of modern art.

JNYes, it’s definitely connected to the contemporary art dialogue. In another piece by Galanin called Your Inane Perspective, he’s doing a somewhat Duchamp-ian thing, where he’s photographing found objects. But it’s the language that’s important. And that seems true to the perspective that you bring to your words and your phrases, this idea that you don’t have to really do anything, you just put it there and let people run with it.

ERYes, so in a sense this could be construed as something almost like a readymade, something that you find in the world and record. He probably goes through a process that we do not understand. I’m not surprised that more young artists are doing this same type of thing today. Their work doesn’t necessarily look alike, but it comes from a lot of the same sources.

JNYes, from plumbing language and explaining its possibilities. Another artist in the show is named Allison Warden, she is also a Native Alaskan artist. She’s a rapper, Twitter poet, and performance artist. We’ve incorporated her work into this show by scattering a number of her Twitter poems throughout the galleries. Her work is simply language, it doesn’t have any physicality to it. It’s just out there and you can put it wherever you want. Though I still feel like it corresponds in a way to some of the things that you’ve done. It’s all based in language, the various meanings that we can derive from language, and particular combinations of words. I really like the conversation that develops between your word paintings and the works by young indigenous artists. It’s almost like you’re sitting down at a table with these people, and you guys come from different perspectives but you all have something to say and you find each other fascinating.

ER[Warden’s work] on its own would traditionally be considered more exclusive to the world of poetry and not really connected to visual arts. But people today are media-jumping and blending all the mediums together. Now you can dance on this stage and have it be considered art. It’s just brought to us into a different context.

JNAnother artist in the exhibition, Wilson Díaz, who has two different bodies of work included is from Colombia and he’s very focused on the coca plant and its significance to Colombia, especially the transformative quality of coca and how it’s been used for cocaine. He wrote out, using coca seeds, all the different indigenous words for coca. So he too is using the power of language to suggest. You have the chemical name of coca and then the indigenous names and you can see that all the names are related to a purpose. Coca has a very deep history with healing and sacred rituals. He’s another example of an artist using language in the twenty-first century as a way to present perspectives on identity. Also, there’s a section of work in the exhibition that I like to call “Paintings and Prints made with Weird Stuff.” Which is one of your specialties, right Ed? [laughs]

JoAnne Northrup and Ed Ruscha with the artist’s Chocolate Room (1970, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, September 2017

ERWell, I’ve gone through some stages that I look back on with puzzlement. But I just got tired of one medium, so I wanted to check out something new. For example, I’ve used pastel and gunpowder.

JNAre those works combustible?

ERWell, none of them have exploded yet [laughs]. But I suppose there’s always a first time for everything.

jNI sincerely doubt if anyone who owned one of these works would allow a match to be near it.

ERBefore I started using gunpowder, I was using graphite, which was greasy and difficult to use. Gunpowder was more pastel-like, errors could be corrected a lot easier. It had a totally different feel to it, and so I just adopted that for a few years, to make art.

JNYou have a pretty good job, huh?

ERWell, I guess. I take my lunch pail to work.

JNA workaday guy?

ERYeah.

JNMore weird stuff. This is a painting with Pepto-Bismol in the media.

ERWell now, this is an oil painting where I left an empty circle that I later filled with Pepto-Bismol. I liked the idea of using that because it’s got a certain identity and look to it.

JNIn 1970, you were invited to participate in the Venice Biennale. The theme was printmakers and printmaking. How did you come up with the idea to work in chocolate? How many candies did you have to unwrap—I want to know everything.

ERI was working in London at a place called Electo Workshop. They made silkscreen prints and etchings. I was there for a few weeks using alternative materials like axel grease, caviar, chocolate, and dairy cream. The Venice Biennale invitation came and so I found myself there, not knowing what I was going to do. It was an off development of the idea that I had been working on two weeks earlier. So I thought, “Maybe I’ll continue this,” and see it with some newer vision. I was given a room and I was given a silkscreen printer, and the idea of making shingles and shingling the walls with pieces of paper covered in chocolate, actual chocolate. I was just completely absorbed by it. We had to find enough chocolate in the city of Venice to produce this thing and it became a kind of a frenzied operation. I had a friend named Brooke Alexander, who has a gallery in New York, and he dropped everything to help me find all theses Nestlé tubes of chocolate. And I think we bought every last one of them in the city of Venice. I don’t know if they ever recovered from that. [laughter] It was a matter of pretty much knowing what the limits of the thing were going to be. After we got them all hanging on the wall, I remember exiting for the last time and as I walked out I saw a trail of ants coming in. [laughter]

I was given a room and I was given a silkscreen printer, and the idea of making shingles and shingling the walls with pieces of paper covered in chocolate, actual chocolate. I was just completely absorbed by it.

Ed Ruscha

JNI believe our exhibition is the fifth time that the chocolate room has been made. Each time it’s made anew. So those are not tiles with Nestlé chocolate from 1970. We made it with Hershey bars this time, all the Hershey bars at Costco. I just love that this work redefines printmaking, it’s not about prints carrying an image, it is an immersive installation. It’s brilliant and it holds up perfectly well over the course of time. Everyone loves that installation, I’m so happy that the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles lent us this.

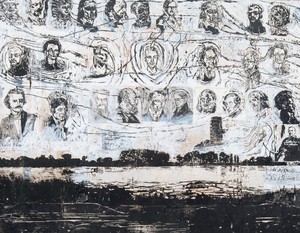

The second time you represented the United States in the American Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was in 2005 with a piece called Course of Empire after Thomas Coles’ series from 1833–36 with the same title. Your perspective on Course of Empire is quite different than Coles’. Could you tell me anything about those paintings?

ERIn the 1990s I was trying to air some thoughts and images with architecture and profiles of domestic buildings. I painted these pictures all in black and white, and I had an exhibit of these paintings, but then nothing ever came of it. So I still had all these paintings and then around 2000 I saw Thomas Coles’ paintings at the New York Historical Society. I loved his title, The Course of Empire. He painted pictures of a savage state in one scene and then people move in and create a civilization, and then the third painting has a flourishing society, and then the fourth one depicts the battles and destruction of this city, and then the fifth painting it is almost back to the savage state. It’s more philosophically on the money as far as the way civilization is going. He painted his pictures quite different from mine. His scenery was not always taken from the same spot like mine. Anyway, I made new paintings that acted as updates of my original black and white paintings, but I did them in color. That’s basically the format for this series. There’s a painting on the right that’s an answer to the one on the left.

JNYou have done some curating and I wanted to discuss the notion of the kunstkammer, or the cabinet of curiosities, which are displays that bring together the natural, the artificial, the exotic, and the man-made to create a wonderful combination. In fact, that really inspired the creation of our exhibition, in that we are trying to channel through twenty-first century eyes, the notion of bringing these disparate things together to present a fascinating conversation between objects.

ERI was invited to Vienna to go through the collection at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. They also have an archeological museum there, so there are two great depositories of art and archeology. Somehow the phrase “The ancients stole all our great ideas” was swirling around in my mind and I thought, well this would make a great title for what I’m going to do here, which is to borrow works from past histories in the world of painting. I managed to get two Pieter Bruegel paintings and some Raphael paintings. From the archeological museum, I borrowed a stuffed coyote. And there was a meteorite from Arizona. This has been done before, they invite different artists to come in and look at the collection and then borrow pieces to make an exhibit. Sometimes the artists will put their own work in as a contrast. I didn’t really want to do that. But I was very happy with the way it turned out.

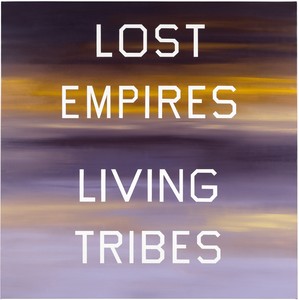

Ed Ruscha, Lost Empires, Living Tribes, 1984, oil on canvas, 64 × 64 inches (162.6 × 162.6 cm), Marciano Collection, Los Angeles

JNAn artist included in the exhibition named Wendy Red Star is a Crow Indian and she created a series called Four Seasons, one of which is called Indian Summer. She’s using actual ceremonial Crow objects in the image, but she also has also included a lot of fake things, and I love how that corresponds to the notion of the Kunstkammer, the combination of fantasy and reality. Her work is in conversation with your piece Lost Empires, Living Tribes. What is this work about?

ERWell, sometimes words come to me in different ways. I have a way of maybe taking a word or combination of words, adding my vision to it, and making it official by making a painting of it. It’s really that simple. I just liked the combination of words—it wasn’t meant to direct anyone’s line of thinking down a particular avenue. In other words, I’m not really trying to communicate with anyone through this. It’s just a combination of words that are blunt and focused in their own way.

JNAnother work, this time by Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, who is a member of the Flathead Nation, is a painting called Herding. The work is about borders and how constructed borders impede on the migration of people and animals. The notion of the West that your cowboy picture is espousing. Or at least it feels cinematic. Pairing these two together shows completely different perspectives.

ERWell, I don’t know what makes it romanticized, but I was trying to get away from hard edge. In fact I was trying to get away from a lot of things, and smoky images helped me get out. That’s why I started making silhouettes. This is one of them. I can’t really say much more about this, except that it has some little snippet of time. Though there’s no specific connection to time—it could be today or it could be in 1840. And I liked the idea that it was timeless.

JNFinally, I just want to talk a little bit about desert artists, of which you are one, because you spend a lot of time in the Mojave Desert, isn’t that right?

ERI do spend time there, though I don’t, you know, set up a canvas.

JNNo plein air paintings?

ERNo, but it informs me. I love the desert and then I bring that experience back to the city in my head. It just twists itself around and gets down into my work in various ways. I don’t adapt the imagery of the desert particularly, but I am inspired by it.

Artwork © Ed Ruscha. Special thanks to Ed Ruscha, Mary Dean, JoAnne Northrup, Amanda Horn, and the Nevada Museum of Art. Unsettled is on view at the Nevada Museum of Art through January 21, 2018. It will then travel to the Anchorage Museum in the spring of 2018 and the Palm Springs Art Museum in the fall of 2018.

Gillian Pistell writes on the loaded symbol of the American flag in the work of postwar and contemporary artists.

Jacoba Urist profiles the legendary collector.

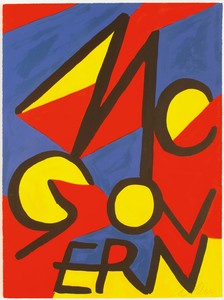

Against the backdrop of the 2020 US presidential election, historian Hal Wert takes us through the artistic and political evolution of American campaign posters, from their origin in 1844 to the present. In an interview with Quarterly editor Gillian Jakab, Wert highlights an array of landmark posters and the artists who made them.

Lisa Turvey examines the range of effects conveyed by the blurred phrases in recent drawings by the artist, detailing the ways these words in motion evoke the experience of the current moment.

Gwen Allen recounts her discovery of cutting-edge artists’ magazines from the 1960s and 1970s and explores the roots and implications of these singular publications.

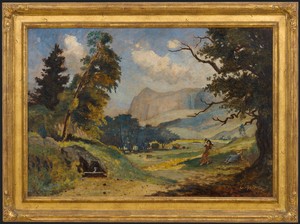

Ed Ruscha tells Viet-Nu Nguyen and Leta Grzan how he first encountered Louis Michel Eilshemius’s paintings, which of the artist’s aesthetic innovations captured his imagination, and how his own work relates to and differs from that of this “Neglected Marvel.”

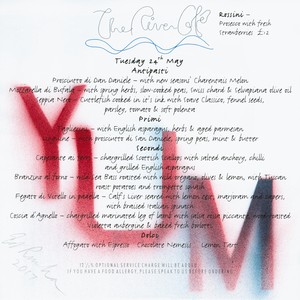

London’s River Café, a culinary mecca perched on a bend in the River Thames, celebrated its thirtieth anniversary in 2018. To celebrate this milestone and the publication of her cookbook River Café London, cofounder Ruth Rogers sat down with Derek Blasberg to discuss the famed restaurant’s allure.

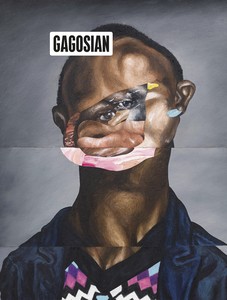

The Fall 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Sinking (2019) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn on its cover.

In conjunction with his exhibition VERY at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebæk, Denmark, Ed Ruscha sat down with Kasper Bech Dyg to discuss his work.

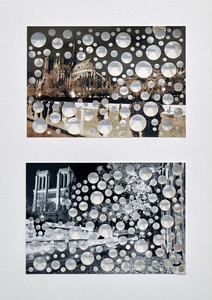

An exhibition at Gagosian, Paris, is raising funds to aid in the reconstruction of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris following the devastating fire of April 2019. Gagosian directors Serena Cattaneo Adorno and Jean-Olivier Després spoke to Jennifer Knox White about the generous response of artists and others, and what the restoration of this iconic structure means across the world.

An exhibition at the Broad in Los Angeles prompts James Lawrence to examine how artists give shape and meaning to the passage of time, and how the passage of time shapes our evolving accounts of art.

Ed Ruscha sat down with Tom McCarthy and Elizabeth Kornhauser, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to discuss the nineteenth-century artist Thomas Cole, whose Course of Empire paintings inspired a series of works by Ruscha more than a century later.