Leta Grzan joined Gagosian Beverly Hills in 2011 after working at Mitchell-Innes & Nash and Christie’s. She has worked closely with the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, mounting exhibitions of the Times Square Mural in 2002 at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, and later resurrecting the Greene Street Mural in 2015 at Gagosian’s Chelsea gallery.

Viet-Nu Nguyen has been the curator of the Ovitz Family Collection in Los Angeles since 2007.

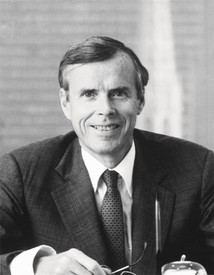

Ed Ruscha’s deadpan representations of Hollywood logos, stylized gas stations, and landscapes distill the imagery of popular culture into a language of cinematic and typographical codes that are as accessible as they are profound. Ruscha has had twenty-one solo exhibitions with Gagosian since his first exhibition with the gallery in 1993. Photo: Gary Regester

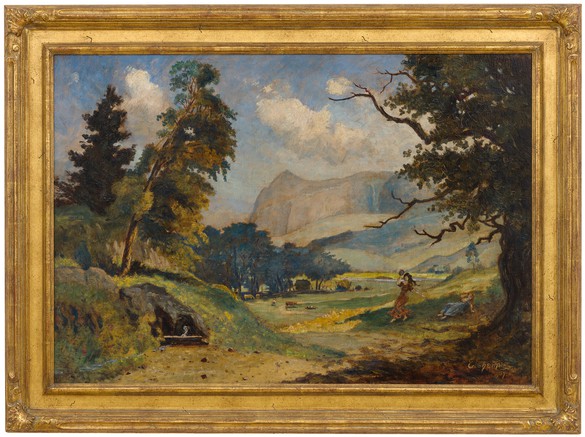

Ed Ruscha I was introduced to Eilshemius’s work by my friend Paul Karlstrom, a scholar from San Francisco who is with the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. In the late ’70s, Paul had taken great pains to make a book about Eilshemius’s life and art, and it was there that I saw the first reproductions. Later I found out that some of my friends, like [the artist] Peter Schuyff, collected his work.

Leta Grzan What was your initial reaction to the work?

ERThe first few times I saw the works in person, I would sort of grab myself and say, “Well, this is not my type of art, is it? Why would I be interested in this man’s work?” But it did interest me, primarily, in the beginning, because he was interesting. He’s almost like a character out of a Victorian novel. He was born wealthy and lived well almost all of his life until the end of it, when he was destitute.

Viet-Nu NguyenYes. He was a lifelong bachelor and completely infatuated with his mother.

ERExactly. In addition, he pictured himself as knowing a lot about the world. He would write these letters to the editor of the New York Sun, using pseudonyms like “God of Art” and “Neglected Marvel,” “Versatile Inventor,” “The Very God of Lyricism,” “Wonder of the World.” How about that? There’s also something unpredictable and contrarian about him that I was drawn to—I’ve read a few of those letters and they’re very funny. He finishes one off by saying, “The tendency of the New York press to brush me aside continually will not be tolerated by, Yours sincerely, Louis Eilshemius.” I like that sign-off.

This complexity makes him—alongside his work—a very compelling voice in the art world. There was something dark and clumsy about his work. At the turn of century he was painting pictures that very much reminded me of Marcel Duchamp’s paintings. I could see right away why Duchamp would single this man out for attention. People were quick to call his work primitive and undisciplined, but he actually went to beaux-arts school, he had formal training, but he just went off on his own. He painted so many pictures in the first two decades of the century and then suddenly, in 1920, stopped painting altogether, except for his last two paintings from 1937. The one of the burning zeppelin, a nod to the crash of the Hindenburg zeppelin in New Jersey that year, is a particular favorite—what a way to cap off your life as an artist, to be doing all these little nymph paintings and then finish it off with one of a zeppelin burning [laughter].

He’s an artist’s artist. He’s completely vanguard. I put him in the category of somebody like George Ohr, you know, the Mad Potter who also was a self-proclaimed genius.

Ed Ruscha

VNHis biography definitely adds to his likability. The art world loves an eccentric, a tortured soul. He was a voluntary outcast. It’s interesting that he cared so much about what critics thought. After all, why bother writing those letters if you didn’t really care to be part of the established art world?

ERWell, he didn’t like to be put down. I don’t think he appreciated that, so maybe he did care about how he was received. And for a long time, he was just a product of neglect from the art world. He would try to get anybody to come to his studio, to the point of writing to people saying, “Come by my studio.” And then he’s got all these little side interests, like he writes poetry, he publishes a magazine, and he offers classes at his studio on how to make frames [laughter]. Have either of you seen this personal publicity handbill from 1910 that he put out? I’ll read it to you: “You make money by making your own picture frames. How to make picture frames your own self can be learned by taking lessons at 20 dollars an hour of Louis Eilshemius, MA, who has recently discovered an easy way to create them. His self-made frames are very light in weight, do not break, are attractive, no wood is used, made with little labor, are luminous. learn.” The word “learn” in all caps. But what did he use, plaster or something? What would he use?

VNMaybe he was referring to his practice of painting frames onto the actual paintings.

ERYes, perhaps. He had this unique way of painting frames with a shadow on two sides and a flash of reflection on the other two sides. And he did that with most of his paintings. The dark is usually at the left and the top and the light is on the right and the bottom.

Beyond the uniqueness of his character, my interest continued as I started discovering other things in his work that were really pretty good, like the way he deals with trees. He’s got trees that kind of talk, you know, the way they’re growing and pointing, and they seem to gather and grow in from surprising places in the composition, almost forming frames of their own around the picture.

VNMost of his paintings are deeply American in location, and the titles make this even more clear. He seems to have preferred woods, forests, and waterfalls, whereas much of your work depicts mountains and deserts.

ERMy use of those types of terrain is not based on love of mountains necessarily, but love of thinking about mountains. It’s more from memory and invention.

VNThey’re not drawn from life.

ERNo.

VNDo you think Eilshemius drew from life?

ERWell, he certainly grew up with that thinking in art—that an artist would go out to a scene and set up a canvas and paint that scene. His work suggests that but I don’t know, there’s so much fantasy . . . certainly he wasn’t seeing satyrs and nymphs out in New York.

LgHe was quoted as saying “A landscape without a nude is incomplete,” and he recommended that other artists take his hint and place their nudes outdoors. Looking at Eilshemius’s work with the frames and your Spied Upon Scene works, you’ve not heeded this advice—there’s an absence of the figure entirely. Could you tell us a bit about that?

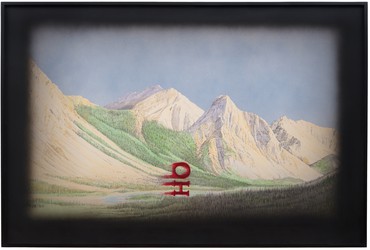

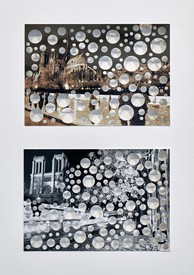

ErI think there’s just a coincidence of imagery that plays against my work and his work that I began to wake up to. It was mainly this idea of the picture frame. My drive in this series was not to create a picture frame but to create an idea that you would be focusing on a trapped vision, like you’re being shown something. This big round black thing with a hole in it could have gone over there, but it doesn’t. They’re just these plastic picture-making methods that seem to coincide.

LGMany of his paintings have—within the frame—this circular motion of bringing you into the center. It’s another way of controlling the composition and the viewer’s eye.

VNIs there any sort of idea of surveillance in your work?

ER I don’t know whether I would call it surveillance or not, but I’m interested in an open view. With the Spied Upon Scene series, the thing I’m interested in is that maybe there was just black to begin with and then it began to open up and suddenly there’s a scene there. It’s like slow storytelling.

VNWhen you look at Duchamp’s work now that you know of Eilshemius, do you find yourself seeing any interesting overlap?

ERWell, when I look at Eilshemius’s work, I definitely think of Duchamp’s work. Some of Duchamp’s earliest paintings were little waterfalls, scenes in the woods with trees, and that sort of thing is quintessentially Eilshemius. Maybe that’s why Duchamp appreciated Eilshemius. They’re two unusual characters.

LGYou were once quoted saying about Duchamp’s Chocolate Grinder [1914], “It was like a mystery that did not need explaining to me. I’ll never need to take an intellectual delving into that subject—not because I’m afraid to, but because I don’t think there would be that much to offer over something that just has its own power.” Do you feel that way about Eilshemius’s work as well?

ERI think that people have tried to dissect Eilshemius’s thinking. They certainly did with Duchamp, especially scholars; but that’s unlike the reaction to Eilshemius. Most people view him as a kind of parlor painter. They were interested in him but they never really dug into him. I’m sure there are people I haven’t read of who have found really interesting things in his work, but the truth of it is that he was obscure for a long time.

VNI think he was, and continues to be, really misunderstood. Due to the subject matter of his work, many thought he was a creep and a pervert, but I bet he never even saw a naked woman in his life, because these nymphs are so perfect: their smooth buxom bodies and their long flowing hair. They read as an idea of woman to me.

LGThey seem to be floating. None of them are quite grounded, so there’s not a reality to them in the picture.

VNThe way Eilshemius depicts women is almost like how you depict mountains. It’s an idea of a woman and an idea of a mountain.

ERYes, that’s a good way to put it. But you can look at these little nymph ladies that he’s painted and they begin to talk to you. I mean, they look like there’s some kind of frustration and some pent-up secrets in this man’s life that prevented him from really opening up, but I think he did through paint. I mean, we could go at it like a psychoanalyst, couldn’t we [laughter]?

VNI think there’d be a lot of sessions involved. But there is this distance in the work, and I think there’s this idea of looking and not touching, of living in one’s imagination, that’s a big part of his work. I’ve noticed this in your work too. You’re looking at those mountains in the Spied Upon Scenes from a distance, almost like a telescopic view.

ERWhen using that halo effect, of the frame or the peephole, it can be like looking into a window or out of a window. And mine, more or less, look out the window. You might say his look into the window. That makes him a peeping tom. And that makes me just a common observer of landscape [laughter].

VNApparently when Pablo Picasso saw Balthus’s work for the first time, he said, “You must be looking at Eilshemius’s work” [laughter].

LGJeff Koons has cited him in the past and is a fan of his work. Henri Matisse, Louise Nevelson, and Ugo Rondinone, among others, have also expressed admiration.

ERThis isn’t surprising. He’s an artist’s artist. He’s completely vanguard. I put him in the category of somebody like George Ohr, you know, the Mad Potter who also was a self-proclaimed genius. So we’ve got these self-proclaimed geniuses to deal with. We don’t have any of those today, do we?

LGThere might be a few I could name [laughter].

VNDo you think he was the most insider-y outsider or the most outsider-y insider?

ERMaybe he tiptoed over the top of the whole thing and then in 1941 said, “Okay. That’s enough. I’m leaving.”

LGDo you think if Duchamp hadn’t found him, he would have been found by someone else along the way?

ERYes. I think it would have been inevitable. He did hundreds of paintings and the subject matter, especially those nymphs, gives his work a consistency that would have been recognized eventually. He was bound to catch the attention of some facet of the art world.

Ed Ruscha artwork © Ed Ruscha; photos: Jeff McLane Studio; Ed Ruscha: Eilshemius & Me, Gagosian, Davies Street, London, June 18–August 2, 2019