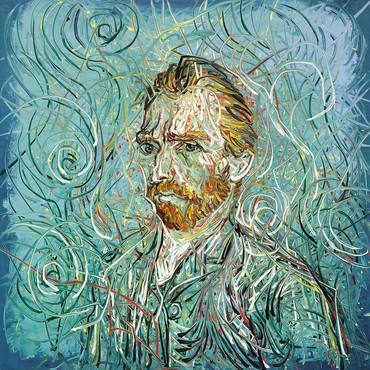

What led you to make these paintings “after” Van Gogh?

Zeng FanzhiTo be frank, if it had not been for this presentation, I would not have thought of making these new works. My previous perception of Van Gogh was limited to a generic idea of “a great artist.” However in the process of creating them, I gradually gained a deeper understanding of him—not as literally as this might sound, but in the sense that I, as an artist, came to perceive the spontaneous emotion of another artist. Creation is sometimes like a game; but at other times it makes you feel lonely, with nothing you can count on. There is no solution, but to keep working on it. It carries a special meaning for me to realize this.

How would you situate Van Gogh? When did you first learn about him?

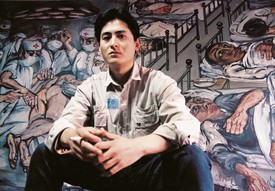

ZFVan Gogh is hard to avoid, not only for Chinese artists, but for artists anywhere in the world. I first got to know him when I was still a student. I came across his works in the March 1980 issue of Meishu, the cover feature of which was dedicated to Van Gogh. In 1982, when I was 18, I bought some posters of his works, among which Hospital at Saint-Rémy, painted in 1889, was my favorite. I even placed it on the wall near my bed so that I could look at it every day. The dynamics of the twisting pines and the unique compositional structure were inspirational. But then for a long period of time, I became somewhat reluctant to discuss him, since he was too popular and talked about so excessively by everyone. This changed when I visited a museum in Europe and saw one of his landscape paintings. I was totally captured by his strong and determined brushstrokes. This led me to re-examine his art. I should stress that his paintings still excite me a lot. I can sense the courage with which he insisted on his own way. However harshly he was criticized, I know he was a man of perseverance. He showed no hesitation in any stroke of his paintings.

In the process of painting a self-portrait, my mentality is best described as “recollecting the past, anticipating the future, contemplating the present,” a state of mind which enables me to better perceive and break through myself.

Zeng Fanzhi

Why did you pick Van Gogh’s self-portraits as your specific subject matter?

ZFThere are multiple reasons. To me, Van Gogh might have been reflecting on himself by constantly turning to self-portraits, making this genre an important area in his oeuvre. The self-portrait served as a window for him to express himself, and he referred to it constantly in his correspondences with other artists. I aim to study him via the same window.

My subject matter is based in this instance on his self-portraits. At the beginning I try to re-experience the way in which he viewed himself as I paint his face on the canvas. There were times he demonstrated confidence, while at others, he showed no desire, as if he were a monk. As I work, I feel like I am gradually befriending a stranger. In the next stage, I add my marks over the painting, using my lines to cover and even “submerge” his face. Eventually I make his image emerge once again from the sea of lines. As I progress, I increasingly have the feeling that I am playing a little game with a friend of mine. Mentally, I feel relief when I create these works. I paint in a meticulous way, attentive to many visual details, but I am not emotionally burdened when I do so and I do not deliberately imbue the works with any special meaning. The more I paint, the stronger the impression I get that Van Gogh is like a character from a fairy tale. I cannot explain why. But as soon as I finish the works, he becomes a legend in my heart.

The self-portrait is also a significant genre for myself. Ever since I was a student, I have been particularly interested in portraiture. When I was 22, I painted by far my most satisfying work, which is a self-portrait of me looking into a mirror. Every time there were important instances and changes in my life, I always sensed a strong passion to paint self-portraits: when I moved to Beijing in 1993 and my life changed forever; in 1996, when the Mask Series reached an important stage—to my mind, at least; and in 2005 and 2009, when I was part of several international exhibitions. In each of these periods, I painted a self-portrait, and collectively they have become a kind of documentary of myself. After each experience of self-observation and reflection, my past is seemingly emptied and I am reborn. In the process of painting a self-portrait, my mentality is best described as “recollecting the past, anticipating the future, contemplating the present,” a state of mind which enables me to better perceive and break through myself. Painting a self-portrait is a process of internal inspection and self-reflection.

Do you view Van Gogh differently now compared to when you were a student?

ZFWhen I was in school, I focused more on his skills, techniques and forms of expression, as if admiring a master. Nowadays, I try to ponder his psyche by considering the historical contexts of his time. Some aspects of his personality are obvious from his paintings and need no verbal explanation. His brushstrokes illustrate his mixed feelings of ultimate loneliness and arrogance. He does not seem confused to me but rather clear-minded and committed; otherwise he could not have painted those strokes with such confidence. All these move me so deeply that they resonate in my inner self.

I know you pay great attention to the interrelationship between art and nature: you emphasize the attainment of aesthetic experience by observing nature. This echoes Van Gogh, who preferred to paint and draw in situ.

ZFI agree with him that one should work hard on sketching in situ. It was this kind of training that allowed my young self to learn what painting truly means. However, my perception of nature has subtly changed, as I have adopted an Eastern understanding: nature as painted is an imagistic symbol, metaphorically signifying my state of mind and ideals. Every one of us is part of nature: we are simultaneously inspired by and reflect it.

How do you perceive Van Gogh? What differences, similarities and relations are there between his style and yours?

ZFI think our styles are drastically different. We live in different eras and are rooted in different cultures. It is natural for our respective art to take different paths. Van Gogh’s inspiration to me is largely spiritual; in practical terms, it should be easy for the audience to identify our differences from our artworks.

Artwork © Zeng Fanzhi