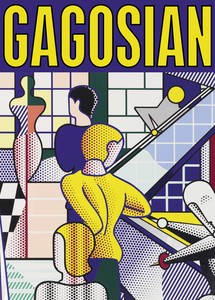

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2024

The Summer 2024 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail of Roy Lichtenstein’s Bauhaus Stairway Mural (1989) on the cover.

Winter 2018 Issue

Dorothy Lichtenstein sits down with Derek Blasberg to discuss the changes underway at the Lichtenstein Foundation, life in the 1960s, and what brought her to—and kept her in—the Hamptons.

Dorothy Lichtenstein in Roy Lichtenstein’s studio in Southampton, New York, 2013. Photo: Kasia Wandycz/Paris Match via Getty Images

Dorothy Lichtenstein in Roy Lichtenstein’s studio in Southampton, New York, 2013. Photo: Kasia Wandycz/Paris Match via Getty Images

Derek BlasbergI’m so happy to be in Southampton in the middle of the week! Normally I only come out for the weekends, but you live here full-time, right?

Dorothy LichtensteinI stay out here as much as I can. We bought this house in 1970. We kept a place in New York for a few years, but eventually we just let it go.

DBWhat drew you guys out here?

DLWe first bought a house with some friends, but with teenage boys it got crowded. At the end of the summer of 1969 we got a call that this house, which was originally just a garage, was available. It had a path to the ocean and my job in those days was going to the beach! We looked at it, said yes, and then came out here the following summer. We didn’t move back for twelve years.

DBI bet in 1970 this town looked a little different than it does now.

DLAre you kidding? In 1970, even the butcher closed and went to Palm Beach in the winter.

DBLet’s start at the beginning: where were you born and raised?

DLI’m a Brooklyn girl. I went to Midwood High School, a public school in Brooklyn, and then I went to a small girls’ college in Pennsylvania, called Beaver College at the time. It’s been renamed Arcadia, but when I went it was called Beaver and there were no end of jokes. Arcadia has now become a serious art school.

DBYou didn’t study art in college, did you?

DLI studied political science but I did minor in art history. My family was completely involved in Democratic politics, that was their social life and their political life—my dad was eventually a judge in New York. So I’m a genetic Democrat. After school I came back to New York and got a job in a small art gallery on the Upper East Side called Bianchini Gallery. I started in 1963, and in 1964 we did this great exhibition called The American Supermarket, which is how I first met Roy. We asked Roy and Andy [Warhol] if they’d put an image on a shopping bag. I met Roy when he came in to sign the shopping bags.

DBWow. I wonder where those shopping bags are today.

DLWell, they’re around! I have a pretty battered one. Back then, no one could have known what was going to come of this moment. When I met Roy, I had a broken leg and I was in a cast. A few people like George Segal and Claes Oldenburg signed it, which I think about sometimes, because back then, after several months I didn’t care who’d signed it—I wanted it off and I never wanted to see it again.

DBThe idea of preservation and conservatorship didn’t apply at the time.

DLHonestly, no one actually thought that anyone was going to make it really big. Back then, a “successful” artist was someone who didn’t have to have a day job, like drive a cab or teach at art school, to pay the bills. You’d made it if all you had to do was your art.

DBDo you remember the first time you and Roy laid eyes on each other?

DLIt was when he came in to sign these shopping bags. But at the time he had a girlfriend he was seeing, and he had promised her that he’d take her to Paris when he had his first show at the Sonnabend Gallery there. The good soul that he was, he took her and then called me up when he and she had separated officially.

DBDo you think anyone working and living at the time had any idea that they were on the verge of an artistic moment or revolution or culture shift? Could you feel something in the air?

DLWhat I felt in the air as a culture shift was more political. The real changes didn’t start happening until the end of the ’60s—Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, two Kennedys were shot, the Vietnam protests. Yes, some things were happening in the art world, but even within that there was all this other political stuff happening.

DBI’m curious because my generation glamorizes the ’60s so much and I always wonder if it was as great as we portray it in films and in fashion.

DLYou know what? It was! It was really free, with a sense that the world was changing. Even the idea that women could throw away their bras—I remember in the late ’50s, girdles and gloves were a must! The art world embraced it, of course. San Francisco had a really big movement and London too. The whole idea of Carnaby Street was a big thing. But, I mean, maybe Coachella makes everybody feel great now? [Laughter] I do think we knew there was a new freedom. I mean, people were breaking out of the mores. Certainly sex was really a huge part of it. A friend always says, “If you can remember that time, you weren’t there.”

Dorothy Lichtenstein and Roy Lichtenstein, 1968. Photo: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

DBThat’s a good line!

DLBy the ’70s, though, a lot of people had moved away: Bob Rauschenberg moved to Florida, Jasper [Johns] moved up to Stony Point, even Andy bought a house in Montauk. There came to be the idea that you could escape.

DBWhen were you and Roy aware of your relevance in the timeline of art history?

DLMaybe never. He always had this idea that fame is fickle. He would joke that one day someone was going to shake him awake and give him his medication. He certainly appreciated the success, but it was never a defining moment. The first time a painting was sold in the double-digit thousands he got a check from Leo [Castelli] and said, “We’re thousandaires!”

DBWhat do you think about the prices now?

DLI think all money is funny. I mean, nobody really knows what a billion looks like. I mean, I wouldn’t mind having it but I don’t think people can really spend that kind of money. The idea of a million dollars used to be huge, but now you can’t even buy an apartment in New York City with it. Money has changed, and now with things like Bitcoin it makes you realize it’s all an abstraction anyway.

DBWhat do you think Roy would make of the prices today?

DLI think he’d take them with a grain of salt—but he would take them! [Laughter]

DBEveryone has these crazy stories like, “Oh, my grandfather bought a [Jean-Michel] Basquiat for fifty bucks.” We glamorize the idea of the money curve. I’m sure people ask you all the time what prices were like in Southampton when you moved out here.

DLOf course, and we actually got a really good deal on this land. There was nothing that cost more than $200,000 around here, if you can believe it.

DBDid you still follow the gallery world when you moved out here?

DLI did. We would go in for openings, and there were other artists who lived out here. We had the chance to meet [Willem] de Kooning because he was living out here too. At some point people began to talk about “the Hamptons,” but before that we didn’t even have that term. Prior to that it was still East Hampton or Southampton and hadn’t been lumped together into one fabulous destination.

Roy Lichtenstein and Dorothy Lichtenstein, 1968. Photo: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

DBYou announced last month that the Lichtenstein Foundation was winding down, and that much of its collection is going to the Whitney Museum of American Art. They must be terribly excited.

DLWe’re all really happy about it! The Whitney picked things that are relevant to what they already own or aspire to, but it’s right in our neighborhood. It’s right down the street [from the Lichtenstein studio]! I think it’s just great. But it will take a while, we’re thinking maybe six or seven years, because it’s a study collection that the Foundation has given.

DBWhen did you start making that decision?

DLPractically since it started. I would wonder, “When is this going to be over?”

DBThe New York Times had a great quote from the Foundation’s director, Jack Cowart: “We wanted to get out of the art-holding business.”

DLRoy never wanted a museum. Also, the other artist [the Whitney] has a lot of is Edward Hopper. I love Hopper’s work too. It just seems to make sense, and they’ve already been doing some events at Roy’s studio. I mean, I’d like to see the studio become part of the Whitney—not a Lichtenstein museum, but in whatever way it would be useful to them.

DBI like their educational programs, and they have all this awesome programming. I wonder if other artist foundations will follow suit.

DLSome foundations already do their own thing. The Rauschenberg Foundation has a big residency in Florida, which is amazing. They invite a dozen or so artists every six weeks to come down, some of whom actually get to work in Bob’s studio.

DBThat must be such a treat for them!

DLI think it’s amazing for them. There’s a lot of freedom in it and it’s multidimensional. There are choreographers and writers and curators and artists, so everybody really does a different thing. They plan to go on for a long time and have the resources to do so. I believe Jasper is planning a residency in his Connecticut place. We’re not going to have a residency [in the Southampton house and studio]. Anyone who buys this will tear it down!

DBI hope not!

DLI hope not too, but it’s the way.

Roy was very clean and almost zenlike. He didn’t leave a mess behind. Then I look around at my desk and wonder who’s going to have to deal with this? He had a steady way of working and even living. I used to joke about how predictable he was and he would joke that he should take curmudgeon lessons just to have more edge.

DBTo be more of a tortured artist?

DLRight. But he got to do what he loved to do, you know? And do it well and earn more than he thought he would probably get as a professor. So I think he really appreciated it. He had that genuine sense of being lucky.

Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

The Summer 2024 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail of Roy Lichtenstein’s Bauhaus Stairway Mural (1989) on the cover.

Alice Godwin and Alison McDonald explore the history of Roy Lichtenstein’s mural of 1989, contextualizing the work among the artist’s other mural projects and reaching back to its inspiration: the Bauhaus Stairway painting of 1932 by the German artist Oskar Schlemmer.

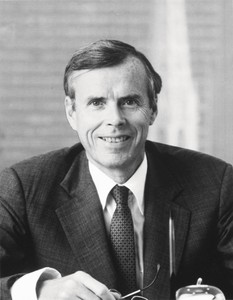

In celebration of the centenary of Roy Lichtenstein’s birth, Irving Blum and Dorothy Lichtenstein sat down to discuss the artist’s life and legacy, and the exhibition Lichtenstein Remembered curated by Blum at Gagosian, New York.

Gagosian and the Art Students League of New York hosted a conversation on Roy Lichtenstein with Daniel Belasco, executive director of the Al Held Foundation, and Scott Rothkopf, senior deputy director and chief curator of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Organized in celebration of the centenary of the artist’s birth and moderated by Alison McDonald, chief creative officer at Gagosian, the discussion highlights multiple perspectives on Lichtenstein’s decades-long career, during which he helped originate the Pop art movement. The talk coincides with Lichtenstein Remembered, curated by Irving Blum and on view at Gagosian, New York, through October 21.

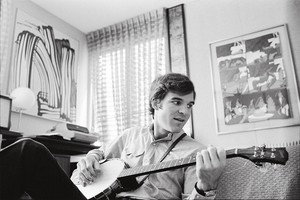

Actor and art collector Steve Martin reflects on the friendship and professional partnership between Roy Lichtenstein and art dealer Irving Blum.

Jacoba Urist profiles the legendary collector.

Against the backdrop of the 2020 US presidential election, historian Hal Wert takes us through the artistic and political evolution of American campaign posters, from their origin in 1844 to the present. In an interview with Quarterly editor Gillian Jakab, Wert highlights an array of landmark posters and the artists who made them.

The Fall 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Sinking (2019) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn on its cover.

Jenny Saville reveals the process behind her new self-portrait, painted in response to Rembrandt’s masterpiece Self-Portrait with Two Circles.

Gillian Pistell examines Roy Lichtenstein’s aesthetic developments in the years 1961 to 1965.

The Winter 2018 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available. Our cover this issue comes from High Times, a new body of work by Richard Prince.

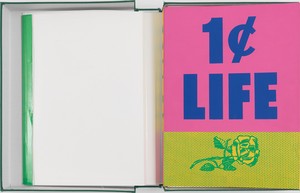

A 1964 publication by the Chinese-American artist and poet Walasse Ting and Abstract Expressionist painter Sam Francis.