Gillian Pistell joined Gagosian in May 2017 as a researcher and writer. She received her doctorate in art history from the Graduate Center, CUNY, in February 2019. Prior to Gagosian, she worked as a research assistant in the Modern and Contemporary Art Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and has contributed to several scholarly publications, including Pen to Paper: Artists’ Handwritten Letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

In the autumn of 1961, performance artist Allan Kaprow arranged a meeting between Roy Lichtenstein and Ivan Karp, director of the influential Leo Castelli Gallery in New York. The purpose of the meeting was to show Karp four of the new “comic book paintings” that Lichtenstein had recently made. The paintings, The Engagement Ring (1961), Girl with Ball (1961), Look Mickey (1961), and Step-on Can with Leg (1961), featured cartoon-like depictions of mass media imagery, some taken from comic books while others from advertisements, and combined elements painted by hand with concepts borrowed from mechanical reproduction.1 Namely, Lichtenstein utilized the Benday dot method, or dots of color from the four-color process printing system (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black) to create secondary colors and shading. Kaprow recognized the radical nature of these canvases, particularly in the continuing wake of Abstract Expressionism. Lichtenstein had developed an entirely new aesthetic language that transformed the visual culture of everyday life into a subject matter for high art—the beginnings of what would become known as Pop art.

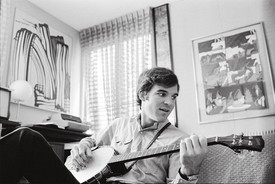

Kaprow and Lichtenstein met while teaching at Douglass College, part of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Kaprow had been teaching at Rutgers since the early 1950s, and had spearheaded what would become a thriving avant-garde art scene, largely motivated by the ideas he learned from musician John Cage, whose classes he attended at the New School in nearby New York. Cage inspired Kaprow—along with numerous other artists of the time—to embrace aspects of everyday life in art, rather than use art as a means to escape life.2 Subsequently, Kaprow penned the essay “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock” two years after the venerated Abstract Expressionist’s death, in which he offered a novel perspective on Pollock’s contribution to the development of avant-garde art: “Pollock, as I see him, left us at the point where we must become preoccupied with and even dazzled by the space and objects of our everyday life, either our bodies, clothes, rooms, or, if need be, the vastness of Forty-second Street.” He went on to clarify: “Objects of every sort are materials for the new art: paint, chairs, food, electric and neon lights, smoke, water, old socks, a dog, movies, a thousand other things that will be discovered by the present generation of artists.”3

Kaprow’s cohorts at Rutgers, including Robert Watts, George Brecht, Lucas Samaras, George Segal, Robert Whitman, and Geoffrey Hicks, likewise assumed this radical stance of embracing contemporary life in art, and it was into this atmosphere that Lichtenstein arrived with his Abstract Expressionist and post-painterly canvases when he joined the faculty in 1960. Lichtenstein’s new colleagues encouraged him to abandon the dominant styles to which he had adhered for the previous several years, and to remember that “art doesn’t have to look like art,” as Kaprow often stated. This encouragement grew stronger when Lichtenstein’s new colleagues discovered his painterly drawings of the iconic American cartoon characters Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. They praised his use of conventional “low culture” for high art, and urged Lichtenstein to further push that notion.4 Consequently, Lichtenstein created the seminal Benday dot, comic-inspired paintings for which he is most known today.

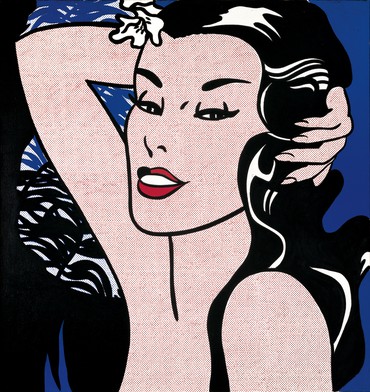

Among these early forays into comic book imagery were numerous depictions of women. Though women would figure periodically throughout Lichtenstein’s career, their appearance as focused subject matter was notably prominent in this beginning phase, from 1961 to 1965. Many take the form of high-drama depictions of women in the throes of emotional angst—typically at the hands of men—from melodramatic scenes in comic books.5 Others, however, were modeled off the ever-present advertisements in magazines and other printed publications like the Yellow Book, a telephone directory that was consistently replete with small, illustrated ads for local businesses. Indeed, two of the four paintings shown to Ivan Karp in the above-mentioned meeting were of women: The Engagement Ring and Girl with Ball. It was these paintings of women that sparked Karp’s interest, specifically Girl with Ball, and prompted him to encourage Leo Castelli to represent Lichtenstein at his gallery.6

The women in Lichtenstein’s 1961–65 paintings are as anonymous as they are beautiful. The predominating palette in these works, of red, yellow, blue, green, and black, emphasizes their mass media sources, while also ensuring that the works maintain a strong compositional integrity—a quality further ensured by Lichtenstein’s method of using a rotating easel which allowed him to rotate his canvases to confirm that their compositions worked when positioned in all possible orientations.7 Girl with Ball, painted in yellow, blue, and red, with bold black lines, falls in this category of depictions of archetypal women; the figure was based on an advertisement for a resort in Pennsylvania’s Poconos Mountains. In the painting, however, Lichtenstein generalized the woman’s features, flattening whatever sex appeal she might have to match the commercialized aesthetic of the Benday dots in which she is represented.8

Karp called Lichtenstein a few weeks after the meeting to inform him that Castelli had agreed to represent him, and Girl with Ball was subsequently added to the gallery’s show An Exhibition in Progress (Bontecou, Chamberlain, Daphnis, Higgins, Johns, Langlais, Moskowitz, Rauschenberg, Scarpitta, Stella, Twombly, and Tworkov), during which Rauschenberg’s works were gradually replaced with those by the other artists in the exhibition’s title.9 Following that show, Girl with Ball entered the collection of the eminent architect Philip Johnson, who then gave the work to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where it remains today. Additionally, Girl with Ball was included in Pop! Goes the Easel, organized by the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston in 1963, along with two other examples of his work, Brattata (1962) and a work listed as Head of Girl (1962), which is today known as Head: Red and Yellow, in the collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York—the pendant to Head: Yellow and Black.

Head: Yellow and Black and Head: Red and Yellow push further the generalization employed in Girl with Ball and other paintings based on mass media advertisements. These works are composites of numerous ads that were ubiquitous throughout the 1950s and 1960s for make-up, hair products, and household goods that often included illustrations of women with universally fashionable features: well-coiffed hair, boldly outlined and made-up eyes, and tinted lips. Many examples of these advertisements remain in the archives of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, and from these clippings, one can piece together the compositions of these paintings. In Head: Yellow and Black, the woman sports a carefully sculpted short and curly hairstyle, reminiscent of that made famous by Elizabeth Taylor in the 1950s. Her eyes are highly stylized, with perfectly arched eyebrows and eyes heavy with mascara and liner. Her features are perfectly smoothed to two dimensions, which works both to make her ageless and to merge her with the yellow and black Benday dot background. She is clearly a representation of a woman rather than a specific depiction of one, glossed over by the ideals imposed on women through cultural demands perpetuated by commercialization like that from which she is modeled. As with the dramatized depictions of women taken from comic books, Lichtenstein here molded the idealized, archetypal woman of his time.

Lichtenstein’s comic book paintings, made between 1961 and 1965, coincide with the years of his separation from his first wife. While the comic book paintings were responsible for launching his career as a Pop artist, and have since become synonymous with his name, they are in fact quite thematically different than the rest of his mature body of work, which largely dealt with high-art subjects and movements. Lichtenstein steadfastly maintained that the narrative aspects of his comic book paintings did not interest him; rather, he used comic book scenes “for purely formal reasons.” The correspondence between these high-drama scenes and the turmoil in his personal life, however, is hard not to notice, and many suggest that perhaps—however unconsciously—Lichtenstein expressed his own emotions through these subjects.10 Though one cannot determine with any certainty that Lichtenstein’s dramatized and idealized pictures of women during this early career are connected to his turbulent personal life at the time, the possibility offers fascinating insight.

Head: Yellow and Black, with its exaggerated Benday dots, bold lines, and reductive palette of black and yellow represents a key turning point in Lichtenstein’s career. He had discovered a radical new direction for art—one that was in its infancy, and that he bravely presented with the encouragement of like-minded artists and supportive gallerists who sought to promote new turns in the American art landscape. Positioned at this critical beginning moment of Lichtenstein’s career, Head: Yellow and Black is not only representative of a turning point for the artist, but can be seen even more broadly as a founding work in the history of the Pop art movement.

1Clare Bell, “Chronology,” in Roy Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, ed. Sheena Wagstaff and James Rondeau (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), p. 346.

2Bradford R. Collins, “Modern Romance: Lichtenstein’s Comic Book Paintings,” American Art 17, no. 2 (Summer 2003), pp. 63–64.

3Allan Kaprow, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” in Reading Abstract Expressionism, ed. Ellen G. Landau (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), p. 187.

4Collins, “Modern Romance,” p. 64.

5Roberta Smith noted this likely association between men—or “boys”—and the mental state of the “girls” in Lichtenstein’s paintings in her review of Gagosian’s 2008 exhibition Roy Lichtenstein: Girls. Roberta Smith, “The Painter Who Adored Women,” New York Times, June 11, 2008, p. E1.

6Bell, “Chronology,” p. 346.

7Dorothy Lichtenstein cited in “Conversation,” in Roy Lichtenstein: Girls (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2008), p. 10.

8“Roy Lichtenstein: Girl with Ball,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79665 (accessed April 12, 2019).

9Strangely, Lichtenstein’s name was not added to the title of the exhibition. One can surmise that his work was a last-minute addition to the exhibition, and that there was not enough time to change the title accordingly.

10For an example of this interpretation, see Collins, “Modern Romance.”

Photos (except Look Mickey): Rob McKeever