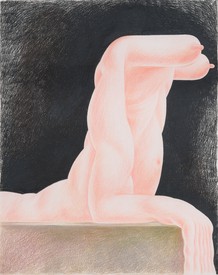

Through softly luminous portraits of bulging, distorted figures, Louise Bonnet probes the experience of what it means to inhabit a body. Her protagonists walk a line between beauty and ugliness, between absurdist, knockabout comedy and extreme psychological and physiological tension. Inhabiting sparse landscapes and boxed in by the edges of the canvas or the page, they act out dramas of profound discomfort that plumb the depths of the artist’s subconscious. Photo: Jeff McLane

I often refer to movies in my head, and they are probably how I learned to understand the world. As a child in cloistered Geneva, I did not have a TV and we rarely went to the movies; my parents listened only to the news or to classical music on records or the radio. I remember they had Janis Joplin’s Pearl and the Beatles’ “White Album,” but nothing much from after 1975. When I would see movies—and as a teenager, when VHS tapes became available—it had a profound effect. If you grow up without that kind of window on the world outside, when it comes in, it’s revelatory.

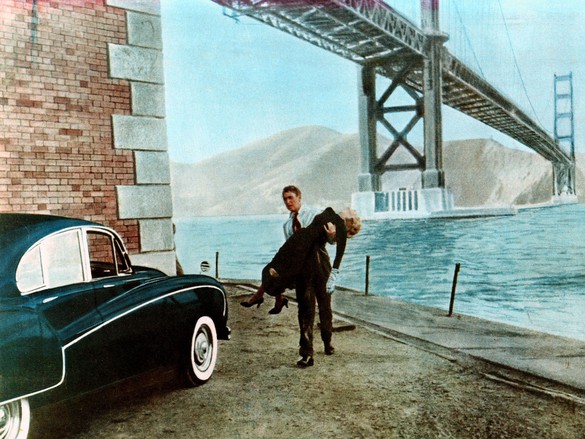

Vertigo, 1958

My mom took me to see Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo at a revival movie theater in Geneva when I was around twelve or thirteen. From the first minute, with its opening title sequence by Saul Bass, I was glued to my seat, and in a way, I still am. I was young enough to be freaked out by the ghost/reincarnation story line and then the narrative took a turn and became scarier and weirder than I could have imagined. There is this incredibly strong armature behind everything in the film—it is so tight, so perfect, even the people are perfect, corseted, contained. Every move and shot and detail is thought through and has a purpose, but they are out of control.

Things are so much scarier if there is a very rational base. Everything seems so normal at first—James Stewart is the epitome of normal—and the result is that you let yourself be led into the depths.

I read somewhere that Hitchcock tried to put lights in Kim Novak’s suit when she comes out and is finally looking the way James Stewart wants her to, so that she would glow in this way that you can’t figure out. It didn’t work, but the idea is so great—magic tricks to make your reality collapse. Tricking people’s brains into thinking what you want, and they don’t even know it’s happening. Like the first scene in Hitchcock’s Marnie (1964), where she is tightly clutching a very clearly vagina-shaped handbag under her arm for a really long take. The whole movie is about her vagina.

I was not surprised to learn that Hitchcock may have been sadistic; he builds these perfect setups for you that look so innocent, and then corrupts them and you in a slow, masterful, voyeuristic way. It’s really magic. I try to use these tricks in my work also. There are things behind that you can’t see . . .

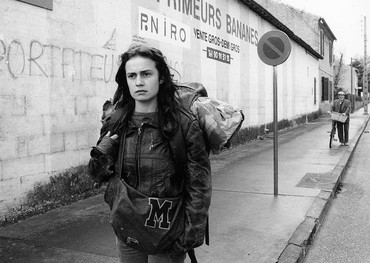

Vagabond, 1985

When Agnès Varda’s Vagabond came out in the 1980s, I was in the middle of being very confused about Madonna. At the time she was being sold (to me, or as I understood it) as a feminist who was unapologetically in charge of her sexuality. This may have been true, but to me her persona seemed to be steeped in exactly what men wanted from women, just in a more aggressive form. Writhing on the floor as a virgin in a bra—was that feminist, and was I supposed to emulate it?

Anyway, I saw Vagabond around the same time, and it was so far removed from any of that—these two women and how they reacted to their environments were so vastly different. I didn’t want to emulate the film’s protagonist either, of course, but she is so mysterious, secretive, complicated, and heartbreaking and so clearly in complete opposition to the Madonna persona. The film never explains why she is on the road and homeless, and she makes no excuses for her actions or behavior. Varda never judges her but rather shows her with unobtrusive empathy—to us she is a real, full human, even though we know almost nothing about her. Shooting on film gives the misery and dirt of her environment a transcendence and dignity; the light and some of the images of the countryside reminded me of van Gogh.

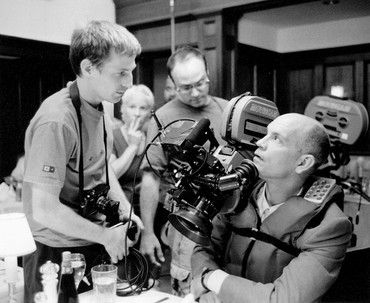

Being John Malkovich, 1999

When I saw Being John Malkovich, I was in LA and working for the streetwear brand xlarge. Spike Jonze, who directed the movie, was around, and had even made a small short for the company. A couple of my friends worked on the movie too, so seeing it was completely exciting and felt really close. But most importantly, it gave me the feeling that you really could do whatever you wanted, that you should do whatever you wanted, that if you just let it fly, you could get, and give to other people, this feeling of being rushed into a wave or something.

Maybe for me the movie captures the feeling of youth, when you are invincible and inventing everything. It’s still rare to see a movie and truly have no idea what will happen next—how did Charlie Kaufman think to write all of this? I hate and love the feeling of intense jealousy when I see something that I think is really good, something that I will never get close to approaching. That usually happens when the artist has let go of trying to get your approval, of trying to be friends with you, the viewer, or listener, or reader. That disregard is insulting and awe-inspiring at the same time.

Under the Skin, 2013

I loved Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin for so many reasons, but mostly all the minutiae. Not much happens throughout most of the movie; it’s just a succession of hypnotic, transfixing images, a mix between 2001: A Space Odyssey and William Eggleston with a slow, whooshing heartbeat. The sounds in it are something I still think about, as well as the lack of sound where it should be. Removing something will sometimes make it more visible.

This is again a movie that doesn’t try to explain itself; it trusts the viewer to understand, and it is full of secrets. I am interested in secrets and minutiae in my own work. You can build trust that people will feel without revealing everything. There is beautiful, precise technique, giving structure and a platform to the movie, to the small details. It is also about control and trying to let go, trying to escape control. Visually it is one of the movies I feel closest to—I love the mix of high and low, of technique at the service of making what is smaller or baser more visible. If you try to constrain and control everything, things will come out in worse, more spectacular, interesting ways, like how squeezing a balloon will deform its shape and make it explode.

La haine, 1995

Everything that’s going on right now—the racial tensions, the well-deserved rage—reminds me of Mathieu Kassovitz’s film La haine. When it came out, French movies (not all, but a lot of them) could still be very old-school, very stilted, with actors enunciating every letter—they were acting. Watching La haine was probably what seeing nouvelle vague movies for the first time felt like. Like nouvelle vague or Italian neorealism, the film looks without sentiment at people and situations that weren’t usually shown in movies. The dialogue is so fast and real, not stylized, and it communicates the deadening boredom and alienation of life in the banlieues. The characters talk about nothing interesting, they’re boring and unlikable as well as funny most of the time, but you know they are real and you care about them. They move through landscapes and through a Paris that has none of its usual romanticized or sentimentalized aspects, and it feels so urgent, so like life. Everything turns in one second that you don’t really see coming, which feels like this is the way it would be in life. There is so much work behind making something that seems completely natural, when you need to be completely fearless so the message will get heard.