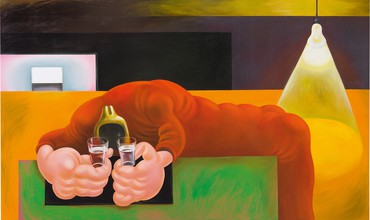

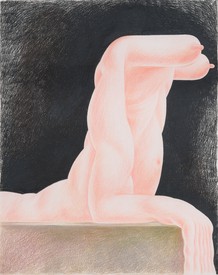

Through softly luminous portraits of bulging, distorted figures, Louise Bonnet probes the experience of what it means to inhabit a body. Her protagonists walk a line between beauty and ugliness, between absurdist, knockabout comedy and extreme psychological and physiological tension. Inhabiting sparse landscapes and boxed in by the edges of the canvas or the page, they act out dramas of profound discomfort that plumb the depths of the artist’s subconscious. Photo: Jeff McLane

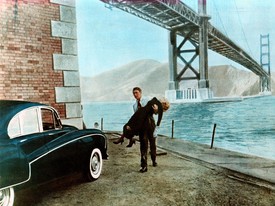

Miranda July is a writer, filmmaker, and artist. Her most recent book, Miranda July (Prestel, April 2020), reimagines the monograph as an oral history on her career to date. July’s story collection No One Belongs Here More You won the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award for 2007. She wrote, directed, and starred in the feature films The Future (2011) and Me and You and Everyone We Know, which won the Caméra d’Or at the 2005 Cannes Film Festival, a Special Jury Prize at that year’s Sundance Film Festival, and was recently added to the Criterion Collection. Her latest film, Kajillionaire, which she wrote and directed, world-premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival was released by Focus Features in September 2020. Photo: Olivier Zahm

Miranda JulyIt’s funny seeing you onscreen when we now live so close to one another. But I wouldn’t have gotten to see you if not for this conversation.

Louise BonnetI know, it’s been so long.

MJQuarantine wasn’t a good time to be neighbors for the first time [laughs]. I know the point where I came into your life, but will you give the short version of your path, or your painter’s story?

LBI moved to LA in 1994 from Geneva, where I was born. I went to art school in Geneva and then I moved here for a year off, thinking I’d go back, but I never left. I’ve never even lived anywhere else in the States but here. A few years ago, two things happened: I started to try oil painting and it was a revelation, and I decided that I would never care again what other people thought. Which I can’t actually always do, but it was a conscious decision to try and stop thinking about it.

MJWhen was that?

LBI still have the first oil painting I made, so that was 2013.

MJIt’s interesting because I remember you saying you’d figured something out. I remember you actually asked Mike [Mills] and me to come for a studio visit. And I didn’t go to art school, I don’t know the conventions of studio visits, so I remember that struck me. I thought, “What? Why the hell would she want that?” But I think what you were doing was sort of formalizing your practice for yourself.

LBThat’s a good point. To have someone I admire come over and formally look at my work, to put myself out there, felt like a big professional step.

MJI remember you saying, “Okay, I need a gallery now.” I always think it’s interesting: how do you go about that if you’re not super well connected with the local art school or other scenes? And I was like, “Well”—this is embarrassing for me—I was like, “Sometimes when I go into galleries, the people working there recognize me and say hi, so maybe let’s just go to some galleries together.” I was hoping I could be that connection. And so we went around to some galleries and literally not one person looked at either of us [laughs].

LBI remember we went to Hannah Hoffman and we walked around really slowly for a while, and sort of lingered, and they never looked up [laughs].

MJGiving them every opportunity. It’s so crushing when that doesn’t work, when no one recognizes you. It’s not like I’m JLo but I was so ready [laughs]. I was like, “Yes, we’ve got to crack this.”

LBIn a way, that day felt like the beginning of something serious.

MJYeah, now that I think about it, it was another case of setting your intention. You were exposing yourself—you were saying, “This is what I want. I’m open to this.” And then from my point of view, it all happened really quickly after that. I mean, I know I had nothing to do with it. It was just so satisfying to watch.

LBI really appreciated that you would do that with me, and that you wouldn’t be embarrassed or feel like it was beneath you. I needed to find creative ways to get myself out there because it’s true, since I didn’t go to art school here I didn’t have that network. And I didn’t really know how to do it, either. I think the trick is studio visits, to get people to see your work and it can hopefully speak for itself.

MJRight. I mean, in the end, it’s always the work. The right eyeballs have to fall on the work and let it naturally do its job. And now, just looking at your paintings, there are many things I wonder. Can you talk me through how the ideas came for some of these new paintings?

LBI usually actually try to not have ideas, to stop thinking. But this period, this quarantine, is kind of a nightmare for me; to have this panicky endless stream of no plans, no structure, and I was thinking, “How do you structure time so it doesn’t have this feeling of being unmoored?” Being Swiss, I really need plans and lists, and I don’t like unpredictability or spontaneity, really. I was thinking about those medieval books, the books of hours: a prayer book, with text and images, that set out all the times in the day, and even the year, when you were supposed to do certain things and say certain prayers. That seemed so soothing and exactly what I needed. I’m not religious at all, but Christianity has such a good way of structuring things, right?

MJRight. I guess the whole point of that kind of religion is that life is scary without an imposed structure.

I think that’s my whole practice: to freeze the scary things—rage, death—so you can look at them from the outside.

Louise Bonnet

LBYeah. But then they come up with these unbelievably scary things within that.

MJRight [laughs]. Like scary things that are named are better than formless ones.

LBYes. Actually I think that’s my whole practice: to freeze the scary things—rage, death—so you can look at them from the outside. In freezing events, you’re able to remove yourself from all these feelings and fully look at them. And they don’t look back at you. I think that’s why I don’t ever paint eyes. You can be a voyeur.

MJYou said you try not to have ideas—it’s funny, I’m always asked where my ideas come from as a writer and a filmmaker and I try to give an answer like yours, because it’s closer to the truth. It’s coming from the unconscious and the rigor of it is to take care of that unconscious space. How do you take care of that space? Did the book of hours help you to do that, or is there some more direct connection between this work and those books?

LBWell, each of my paintings is based on a time of day. Being stuck in the house during quarantine, I draw from everyday domestic activities. So I realized that that was the structure I needed and I was looking at this book and it came together. The process is not to try to come up with stuff but to let it happen.

I need to be alone a lot to be able to get in touch with this unconscious space. But it’s hard right now.

MJHow did your life change during the pandemic? It’s an adjustment both logistically and mentally to be painting for a future you don’t really understand. I know on the one hand, we’re people who don’t go to work in the same way that people in other professions might; our work is self-generated. So that’s good. But this thing of the kids leaving the house to go to school is also crucial [laughs], as it turns out.

LBI really like having a deadline, which comes back to the need for plans. But aside from that, I was able to terrify my family enough that they would leave me alone and let me work—otherwise it’s just such a nightmare at home [laughs]. I mean, I do need to deal with everyday stuff for the kids being unable to have a normal life. But in a way, aside from this anxiety—anxiety about the future and the state of things—day to day it’s not that different, actually.

MJRight.

I want to see work made by women of this age. It seems valuable to me, and something that’s largely missing.

Miranda July

LBAnd right now, [my husband] Adam is taking care of a lot of the family stuff and I am so lucky to have someone who is completely supportive and encouraging. But I have to say that also, when I decided to really put myself out there with the paintings, it coincided with my last kid going to school for a period of time long enough that I could sustain a train of thought.

MJI think it’s important for people to hear that—that there are many different ways a painter’s life can look. There’s this emphasis on starting at this particular time in your life when you’re very free, but the truth is, you will find your freedom. You’ll find opportunities to reunite with your mind. And it’s a great mind—your mind at this age I feel is a pretty special thing. I want to see work made by women of this age. It seems valuable to me, and something that’s largely missing.

LBI can’t remember who said that your life doesn’t have to be chaos for you to make great art. This tortured-artist myth—I mean, I’m sure some people are like that, but you also don’t have to be at all.

MJIt’s such a privilege, the tortured-artist thing. You either have to be a man with a wife who’ll take care of everything or really wealthy. I think part of me would love to be more tortured, but I just can’t afford it [laughs]. My torture tends to end at six every day. You know, there are real responsibilities. There shouldn’t be one kind of artist’s voice we get to hear.

I was looking at what I see as these kind of vaginas in the tops of the blonde hair that you painted, and I was thinking about vaginas and breasts and how consistent these images have been in your work. You have this voice—or rather, it can look that way from the outside, codified and consistent, but there’s actually constant transformation there, and realizations that no one else knows about. So I’m wondering how your painting language has changed, and what you’ve become more or less interested in over time.

LBI think it’s just that I do need to work every day and not see anyone and just do it, and things change on their own. I get more confident and interested in more of what’s hidden, the story behind the painting, rather than showing everything or trying to explain everything. Now I’m more comfortable just being vague—even to myself.

MJRight. Gosh, that sounds nice. I want to screenshot that idea. Hold on, I am actually going to write it down.

That’s sort of the sweet spot, when you let go in that way. I know writing is a different process, but this idea could help me right now: “Just let it make less sense.” There’s more room than you think. One thing that our work has in common, I think, is this mixture of humor and pain—bodies and pain and humor and sex. Often there’s something really quite painful or uncomfortable that I’ll end up writing in a way that is funny to me.

LBYes.

MJAnd it’s really like you’ve redeemed yourself—you’ve redeemed that part of life in a way where it doesn’t lose any of its pain but it’s open now.

LB The feeling doesn’t take full shape if you can’t laugh about it, right? But it’s also funny because I just finished a painting and I’m like, “Oh my God, that’s a penis again.” I didn’t really set out to make a penis.

MJYeah. I think one reason I love talking to you is the space you get as an artist: you get to paint these body parts, these vaginas, these penis-y things again and again, and no one goes, “What’s up with that?” A seriousness is granted. Whereas if you’re in popular culture—

LBPeople are more judgmental.

MJIt really becomes as if you don’t know that you’ve written about butts again and again in different ways, like I have. I’ll be like, “Oh shit, butts come up again in this thing.” And, well, why the fuck not? It’s very limited, what we have here. There are really only a few symbols; whatever is there in your unconscious, that’s what you have to work with.

LBYes, and in addition to humor, I think about the relationship between pain and beauty. Those medieval Crucifixion pictures are so amazingly rendered: dead Christ with these sores and mold that are incredibly detailed and lovingly done. When I saw Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining [1980] for the first time, I felt the same thing: oh my God, you can show these gruesome things and feelings but it’s symmetrical and it’s beautiful.

MJWhen speaking to other artists, I’m always curious about . . . what does it feel like to be you? What’s the speed of your mind? For me, I’m sort of constantly rushing and there’s a voice in my head that’s pretty harsh and admonishing, like I’m in trouble a lot of the time—it’s almost like I’m in a video game or something.

LBI think one of the big things I have is a feeling of being trapped, of trying to escape many things. But I’m a coward too—I can’t do drugs, for example, I’m scared of that stuff. So being able to be in my studio and paint and not think and listen to audio-books is my escape. Just now I’m listening to the history of Deutsche Bank: it’s interesting, but it’s not going to overwhelm and interfere. The audiobook makes me mad, but it’s sort of like this invigorating outrage-y feeling, you know, like coffee. But basically, I think, in my head, the main thing is I’m trying to escape everything all the time.

MJGod, I’m really with you on that [laughs]. I was looking at your paintings and thinking how, for a director, light is everything. It’s emotion. That’s always a big question, what I want the light to be like in my films. You’re working with light too, but you have to create the light. It’s not from electricity, or from the sun; you’re making it. The things that are so teeth-gritting to me about your work are the different opacities and sheens and densities and volumes—so much of that is light.

LBActually, that was what happened with oil. You can do that with oil, manipulate light. I mean, some people can do it with other mediums, but with oil you can have really thick, deep, filled-in colors. Sometimes it feels like the medium does what you want on its own. It’s just amazing.

MJWild, yeah.

LBI don’t know if people who went to school to study oil painting are used to it, but I’m still amazed.

MJRight. Some of it is just pure joy in getting to work with the medium. How lucky it is that this medium actually holds meaning on top of its form.

LBI couldn’t do anything else, really. Which is why what you’re doing is so amazing, being able to move between art forms—writing, filmmaking, performing. You’re like this flower bush that can grow all these different leaves and flowers and buds and succeed at making them all wonderful. I’m more one of these cacti that just go straight up and that’s it, until they get a fungus and fall over at some point.

MJIt’s really just that I’m counterdependent. That’s a new phrase I’ve learned, meaning, I never want to be too dependent on a person. And I now realize I’m the same way with my work. I choose not to be artistically monogamous as a form of security, because I can’t trust anyone or anything [laughs]. Anyways, we’ll work on that later. I do actually have Zoom therapy after this so I’ll just move right on into that [laughs].

I relate to the way you use reality to the degree that it’s useful—as a sort of common code, but not as our only common language or even our most effective one. Are there times when your work becomes too real, or else too abstract? Is there a line you can walk that feels the best to you right now? I’m thinking about what you were talking about earlier, about getting to be vague. I imagine that has to do with how much you literally need to tell a story. Could you talk more about that?

LBRight now, I feel like I want to tell a story more, because everything’s so bizarre. Someone said the paintings I’m currently making are like allegories of something.

MJLike collecting the tears.

LBYeah. I do go back and forth with trying to be more abstract. I always thought removing stuff was the way to go, but now I’m not actually sure anymore. Right now I’m actually wondering if I should add stuff, like more threads of stories, and environments in which you can really get lost.

MJThat’s making me think of a genre I’ve seen: paintings of rooms where every detail of the room is a world. You feel like you’re there, like you could almost walk around in that room. That’s what I imagined when you said that.

LBYeah, those types of enthralling environments. I’ve done many paintings in the past that feature one figure; now, more people are appearing in my work. I think with more than one figure, relationships emerge, and you can make a story in your head about them.

MJYeah, you can. I noticed I was doing that—I was trying to see secrets. Well, I can’t wait for your opening. I know it may not happen on schedule, but I can’t wait for when it does. I heard a therapist say on the radio that it’s really important for us during this time to plan events in our future, even what we’re going to wear—it helps our mood. That’s going to be one of the events in my head to get me through this: Louise’s opening.

LBI want to see what you’re going to wear.

MJI want to stand among many other admiring people and look at your new paintings. The thought makes me want to weep.

Artwork © Louise Bonnet; photos: Jeff McLane

Louise Bonnet: The Hours, Gagosian, Park & 75, New York, September 29–November 7, 2020