Ali Subotnick is an independent curator based in Los Angeles. She is adjunct curator at the Hammer Museum, where she was previously curator (2007–17), and curator-at-large for Los Angeles Nomadic Division (LAND).

The characters who populate Louise Bonnet’s surreal universe exhibit extreme abnormalities; headless figures with gargantuan noses, peculiarly shaped breasts, inflated butts, and oversize digits and limbs bend, twist, point, poke, and prod, revealing both their extraordinary capabilities and their limitations. With the flexibility of Plastic Man or Gumby, each gender-ambiguous creature provokes an undeniable discomfort, as we reflect on our own humanity and corporeality. In short, Bonnet makes you squirm. She counts fine artists such as Philip Guston and Peter Saul as influences, as well as comic illustrators including Tex Avery, R. Crumb, and Basil Wolverton. Bonnet grew up in a time when comic artists were highly regarded for their deft technical abilities and vivid imaginations, and she regularly read Métal hurlant (Howling Metal) and Tin Tin, among other classics of the genre. Mashing up bits and pieces of those influential artists with her own distinct visual language, Bonnet’s contorted figures expose our inescapable physicality, and how at times—if not all the time—we humans can feel deeply awkward and uneasy in our own skin.

Bonnet started out making traditional figurative paintings and drawings, but she recalls a very clear moment when things shifted for her. She had become increasingly disinterested in the images she was producing and kept thinking about how they would be received by others, especially her artistic heroes. She grew so tired of these voices in her head that she decided to take six months and focus solely on drawing faces. That intensive exercise ultimately led to her signature inflated, droopy, and swollen noses. The absence of faces—or depiction of only the balloon nose—followed, and continues today, because she never found a way to make them interesting. For Bonnet, exaggerated features such as noses, feet, butts, and hands provided much more excitement and inspiration, while faces tend to attract all of the attention without adding anything. She stopped trying to produce pleasing illustrations and chose to focus on making images that could evoke that feeling of uneasiness in one’s own skin. Working with oil paint expanded things further, so she took a pause from her drawings, which up until then were primarily sketched in ink and tended to be somewhat flat. When she came back to drawing about five or six years ago, the experience of creating these figures in oil paint and those visual images stayed prominently in her mind’s eye as she developed a technique to depict her characters in colored pencil with a substantial illusion of depth and volume.

With this new series of colored pencil drawings, Bonnet relinquishes the full-bodied, mostly erect larger-than-life figures depicted in her paintings, concentrating instead on the form and characteristics of the sphinx. Throughout the centuries, this mythical animal has been represented in a variety of poses and configurations. A hybrid creature, the sphinx is generally composed of the head of a woman (typical of the Greek tradition), the body of a lion, human breasts, and a falcon’s wings. The head of the monumental Sphinx of Giza (a male creature, following Egyptian convention), carved from a single piece of limestone by ancient Egyptians during the reign of the pharaoh Khafre (c. 2520–2494 BCE), is adorned with a royal headdress and represents the sun god, Ra-Horakhty. Bonnet was attracted to the power that the sphinx symbolizes and its embodiment of aggression and rage, in addition to its hybrid composition, fusing animal and human parts, which harks back to shape-shifting characters in her favorite horror and science-fiction films.

Mythologized in the story of Oedipus as a merciless and treacherous animal who guarded the entrance to the Greek city of Thebes, the Sphinx killed (or, in some versions, cursed to death) anyone who failed to answer her riddle: What walks on four legs at dawn, on two legs at noon, and on three legs in the evening? Oedipus proffered an answer: Man, who crawls on four legs as a baby, walks on two as an adult, and in old age relies on a cane as a third leg. Angry and frustrated that he had solved her puzzle, the Sphinx threw herself off a cliff. The riddle, like Bonnet’s characters, reminds us of the versatility and malleability of our bodies, and the physical challenges of aging.

Bonnet takes many liberties in rendering her unconventional sphinxes, transforming the ancient creature into an acrobatic superheroine symbolizing power, transformation, and the infinite possibilities of the imagination. She approaches each drawing with a vague idea of the pose or positioning in mind but welcomes the inevitable discoveries that arise as the image evolves, and if she likes a detail, she might amplify it in the next drawing. Some of the stances are so visceral that we can physically feel the stress on the knees, or the strength and ferocity conveyed through a proud chest and shoulders. Each drawing offers an alternate perspective, highlighting various body parts and postures, mirroring how one might view a sculpture. Bonnet has chosen to provide only partial views of several of her characters, and many of them are cut off abruptly so the full figure is never revealed, leaving us to fill in the blanks.

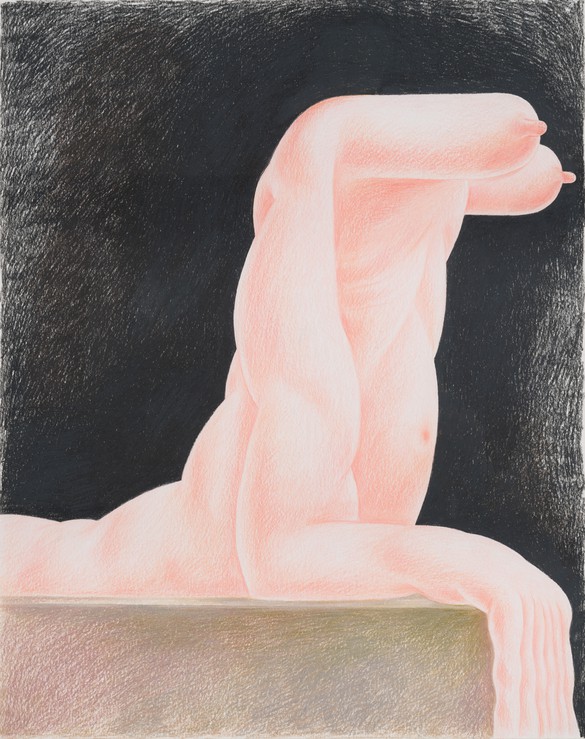

The wry sense of humor and penchant for the absurd at the core of Bonnet’s paintings persists in her drawings. In these grotesque, ludicrous, and endlessly delightful compositions, she playfully explores a variety of exaggerated body parts such as feet, spines, nipples, and breasts as well as contortions and distortions of the human/animal. Like the characters in her paintings, the sphinxes are headless, except for an occasional miniscule hair helmet, which serves as a stand-in for a face or head. In Cobra (2021), the tiny, perfectly coiffed, flipped-out bob rests atop a sphinx’s muscular shoulders with arms extending behind her like wings. The body is only partially revealed, with the arms reaching the edge of the paper well above the elbow. The exceptional breasts on this particular sphinx feature protruding bumpy nipples that resemble coronavirus particles. In this drawing, as in several others, the figure rests on top of a pedestal like a static sculpture; however, the gently curving abdomen conveys a sense of movement, appearing on the verge of rocking back and forth, right off the ledge. The representations of sphinxes on bases imply stillness, yet these creatures live in limbo, arrested mid-motion, paused between transforming from flesh to stone, or vice versa. Some of the bases are in fact depicted as marble with visible veins, as in Seated Sphinx Pink Marble (2021), in which a sphinx adorned in a long green dress sits, knees bent, oversize feet and extra-long (and sort of creepy) curling toes on the floor below.

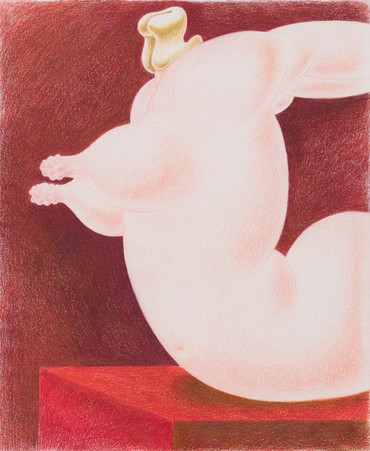

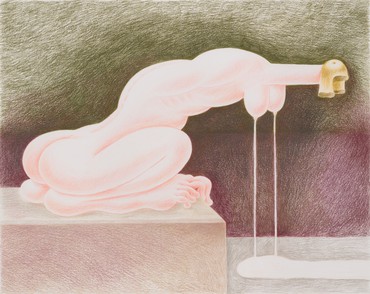

After she began making these drawings, Bonnet recognized a resemblance to the paintings of anthropomorphized, futuristic machines by an artist she admires, Konrad Klapheck, as evidenced in the shelflike breasts of Seated Sphinx Pink Marble. In Crouching Sphinx Red Base (2021), one of the more dramatic depictions of powerful breasts, which also demonstrates an affinity to Klapheck, a small pipelike neck leads to ridiculously long breasts that emit milklike light projections, while the extreme curvature of the spine suggests a serious case of scoliosis. Her thick thighs and bent knees lead to toes that curve up to grip two bulbous butt cheeks. In Heroica (2021), another drawing dominated by the breasts, the sphinx folds over in a backbend, with milk spraying from the prominently puckered nipples and a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it little hairpiece topping the shoulders. Keeping with the body and its liquid emissions, one of the more outlandish and complex drawings (Leaking Sphinx, 2021) depicts a kneeling sphinx whose feet stretch out with its toes gripping the edge. An elongated curvy spine leads to a narrow tubular neck, topped with a Cleopatra-style hairpiece. On the underside, two supple breasts discharge steady streams of milk that pool on the floor below. Like the figures in Klapheck’s paintings, this creature verges on objecthood and could almost double as a sink, with breasts for faucets.

Bonnet’s sphinxes feel more immediate, rougher, and rawer, yet each one, situated between stone and flesh, evokes a visceral reaction.

Several of Bonnet’s sphinxes represented in the traditional kneeling pose, as in Crouching with Toes (2021), portray visceral gestures such as toes delicately curled under and pressing deeply into the bottom. The big toes on Kneeling Sphinx 1 (2021) also poke into the pillowy rear, but from a different vantage, so that we may at first focus on the pressing of the toes, but then the three-quarter view draws our gaze up past the folded knees and torso to the delicately rendered ribs and spine to finally land on another pair of unforgettable breasts that point off the page. These breasts extend out from the shoulders like the twisting balloons used to make balloon animals.

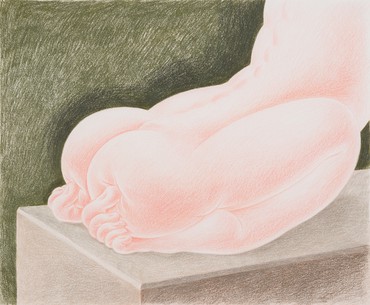

Resembling a guard dog, the protagonist of Resting Sphinx Black Background (2021) features those same erect, protruding breasts that replace the head entirely. Sitting in a cobra pose, she exposes her ample, round abdomen, and we follow her long and muscular right arm down to the elbow resting on the pedestal with seemingly infinite fingers cascading like a waterfall over the front of the base. Not to play second fiddle to the breasts, another drawing (Seated Green Marble, 2021) depicts an ample rump, so thick and heavy that the fleshy pink butt cheeks can barely fit onto the forest green marble base. It’s the type of ass a Kardashian might envy.

Bonnet’s beguiling approach to the classical sphinx lures us in, where we discover less overt gestures and moments—skin folds and juicy wrinkles take on a heightened primacy. Perhaps owing to their smaller scale and the soft rendering of their pencil-drawn forms, these drawings convey a sense of intimacy that distinguishes them from the paintings. In contrast to the fully formed and imposing figures that populate her canvases, Bonnet’s sphinxes feel more immediate, rougher, and rawer, yet each one, situated between stone and flesh, evokes a visceral reaction, but in a less threatening manner, with a diminished intensity that’s perhaps a bit more palatable.

Louise Bonnet: Sphinxes, Gagosian, Basel, June 3–July 31, 2021

Artwork © Louise Bonnet; photos: Jeff McLane