Dodie Bellamy writes genre-bending works that focus on sexuality, politics, and narrative experiment, challenging the distinctions between fiction, essay, and poetry. In October 2021, Semiotext(e) simultaneously published her essay collection Bee Reaved and a new edition of her 1998 PoMo vampire novel The Letters of Mina Harker.

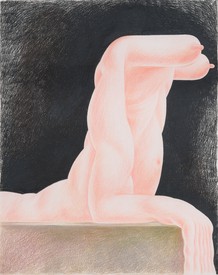

Through softly luminous portraits of bulging, distorted figures, Louise Bonnet probes the experience of what it means to inhabit a body. Her protagonists walk a line between beauty and ugliness, between absurdist, knockabout comedy and extreme psychological and physiological tension. Inhabiting sparse landscapes and boxed in by the edges of the canvas or the page, they act out dramas of profound discomfort that plumb the depths of the artist’s subconscious. Photo: Jeff McLane

Dodie BellamyReading through some of your earlier interviews, I was surprised at the resonance between my experience and your experience. You’ve brought up David Cronenberg’s The Brood [1979], and Cronenberg was an incredible influence on me when I was young. In part because of his engagement with “body horrors,” if we can call it that?

Louise BonnetRight, yes. When I was a kid in Switzerland, we used to go to a town in the mountains that looked a lot like the world in that film—the snow, the buildings, the 1970s fashion. All the adults there looked like those people in that movie, I had exactly the snowsuit that the kids wear in it. So to watch this familiar terrain turn into this horror around the mother and the children, where everything goes through a metamorphosis and people are deformed, was really powerful.

DBIt’s interesting that you use that word “deformed.” When I was reviewing various press coverage of your work, people kept using that word, which I found kind of offensive. I couldn’t believe somebody would call those figures deformed [laughs]. It struck me as arrogant to presume.

LBI know what you mean, but because I love horror movies so much, to me it’s kind of a compliment.

DBIt’s true. And in horror movies there are these transformation scenes, transformations of the body, that are so key, which I see in your work. I even went back and read Ovid’s Metamorphosis, to come at it from another angle—these themes of being in the middle of a transformation. Which brings up another thing I wanted to ask you: what’s your relationship to narrative?

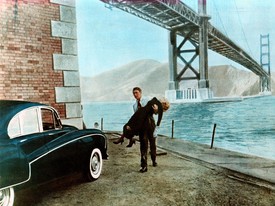

LBBecause my first loves were books and movies, I think a lot in terms of those mediums. Paintings work with time differently from those forms, but I try to explore where they could converge; I like the idea of viewing the paintings like they’re in the middle of a movie, almost like a still. There’s a story before and after what you’re seeing, but it’s not given away. Sometimes I don’t even know what it is.

But back to horror movies, I think they also appealed to me because, at least in a certain subgenre, the women in the films are more powerful than in other genres, and in general, power functions differently across the narrative arc. Power is given to people who usually don’t get much in other movies, right?

DBBut there’s that whole thing that Carol Clover wrote in Men, Women, and Chain Saws [2015] about “The Final Girl,” you know, and how she emerges in the 1970s as this archetypal character that then recurs with great frequency. And she’s usually the virginal figure, of course—

LBYes. But that’s where those Cronenbergs are different.

DBAbsolutely, he’s nothing like that.

LBOr in The Shining [1980], you don’t think Shelley Duvall’s going to come through at all and she does, even though at the beginning of the movie she starts as a classic submissive female figure in the context of that family. That film also truly scared me because Jack Torrance reminded me of my father in some ways, and their family dynamic, without the murder or even actual violence, mirrors something really intense for me.

DBAbsolutely, I think many of us have that experience where the father isn’t by any means a figure of strength and safety, he’s erratic. And one of the scariest parts of the movie is when you read his typewriter.

LBYes!

DBSo it’s like the writing, or creation, becomes a source of horror [laughter].

LBWhy do you like horror movies?

DBWell, it started when I was a kid, but at different ages they’ve appealed to me in different ways. I think a lot of women I know, artists and writers, very much relate to the whole notion of monstrousness, the idea that to be female is to be treated in many ways as a monster in conventional society. In my life and work, I always want to get to some kind of visceral connection, and sex and horror is a place to do that. I was always interested in the visceral, the libidinal. So that’s a through line, but then horror became something else when I had this series of drug flashbacks for five years, so I could really relate to those transformation scenes in movies. When the flashback comes on and everything’s fucked up and creates this energy and tunnel vision—it’s really one of the most terrifying things that’s ever happened to me. That that kind of alienation from one’s physicality is portrayed and meaningful in horror is appealing.

LBMe too, exactly. I had flashbacks too for a while. I was really afraid of drugs . . . well, my mom was really afraid that I’d do drugs, and thought it was the worst thing you could do, which I believed. Because of that, I had no notion of how to use drugs or what they did to you, so when I ate a piece of hashish the size of a pack of gum, it was like what I’d imagine would be having a schizophrenic meltdown. I was really not normal for like,

a year.

DBSee, we really are like twins [laughs]. Do you continue to feel the effects of that?

LBNot as much, but I think that some experiences most people don’t think twice about are more loaded for me because of it. Like, you know when you’re thinking something, but you’re also realizing that you’re thinking it, and you’re judging the way you’re thinking it, so there are two or three people inside of you? Ugh. To get out of the flashbacks and panic attacks then, I became a huge hypochondriac. I would think I was having extremely dramatic heart attacks, maybe vaguely glamorous, now that I think of it, very Madame Bovary. It was a way to deal with anxiety, to obscure it, to trick it on the wrong path, I think, because as I’ve gotten older and started dealing with, sometimes, actual illness, reality is much less cinematic, less glamorous. I wasn’t envisioning the beige plastic bedpans. You know, being actually sick is so less momentous . . .

DBAnd there’s also something about the bureaucracy of the medical system; it’s so dehumanizing that you’re not in control, like you might be in the hysterical moment, actually.

To connect back to what we were saying about transformations and panic-induced or flashback-induced states of being, and how that relates, or doesn’t, to our love of horror movies and our creative practices, do you see resonances in what you’re working on now?

LBI think it’s all linked. The panicking about not being in your body, or being too many people in your body [laughter]—you know, it’s maybe like throwing up, where it stops you, freezes the moment, and then it’s outside of your body, where you can look at it.

DBSo this work in some way is an experiential kind of dysmorphia.

LBDefinitely. When I was a child I had a fever that developed into this thing called the Alice in Wonderland syndrome.

DBOh, I’ve never heard of this.

LBI don’t know if people have it as adults—it’s a kind of hallucination where you feel your limbs growing, it feels like they’re becoming these gigantic balloons.

DBThat reminds me of something else I thought when I was reading about your work. You know how when you’re a child, you basically don’t know the rules of the physical world, and you learn them while growing up? When I was a kid, like very, very small, I would have these two nightmares. In one of them there’d be a rope that was thin and would get thick and would get thin. Another would be some animal, like an elephant, that would get big and small. That’s all that would happen, and it would terrify me.

LBI had a friend who had this thing where she would feel like she was moving back and forth, knowing all along that she wasn’t actually moving.

DBOh, they do that in horror movies!

LBExactly. Something was doing this bouncing thing inside her and she couldn’t control it—and it was rhythmic. I think that’s the most frightening, the rhythmic thing. Because it won’t end.

I like the idea of viewing the paintings like they’re in the middle of a movie, almost like a still. There’s a story before and after what you’re seeing, but it’s not given away.

Louise Bonnet

DBLike the drug flashbacks, there was no guarantee that they were going to end. Sensing that one little thing could change in the brain and you wouldn’t be yourself anymore . . . it’s not knowledge you really want to have, right?

LBIt’s terrifying. The fact that our bodies function at all is just crazy. We went to see the Endeavor, the space shuttle in the California Science Center here. It looks like it’s made of papier-mâché and Scotch tape, the most fragile-looking material. I even thought at first that it was some sort of mock-up, a stand-in for the real thing, but no. To realize that this thing could go up in space—

DBAnd be so fragile-looking? Wow.

LB There were also those pods for the astronauts to fall back to Earth in, and they look exactly like Jiffy Pop popcorn bags. The fact that they had people in there they could contain, the machinery worked and everything, but that’s like our bodies, right? It makes you feel like just one thing could go wrong and it’s over, but the fact that it also goes right just seems so unlikely.

DBI think more people than you imagine have had some sort of experience where they question the stability of their body and their experiences, and your work taps into that.

LBThat’s the negative part of it.

DBYeah, let’s talk about the positive.

LBNo, no [laughs], I don’t mean negative as some sort of moral evaluation; it’s just maybe something people don’t really want to be feeling.

DBAnd the paintings have a beauty to them, as well. Journalists use the word “ugly” a lot in the articles, but you don’t see them as ugly. Or do you?

LBNo, I don’t. But I’m also okay with that description—ugly, to me, isn’t really a bad quality. Maybe that’s also why the figures in the paintings aren’t looking at the viewer, so you can’t really shame them. They’re in their own world, and impervious to judgments of the beauty/ugly variety.

DBThey’re not of our world. I like that. Are they also outside of gender? Some seem more male or more female, but is it more correct to think of them as androgynous?

LBIf they have clear sexual attributes, it’s to show something, but that something isn’t usually gender. I’m interested in seeing what your body does to you rather than defining any sort of limits or separations.

DBThat feels very writerly to me. I’m always telling students about the concept of foreground. If everything’s so detailed, nobody can enter; some things have to be more lovingly cared for and then other things should be more sketchy, so that there’s a contrast.

LBExactly. I’m getting more and more comfortable letting things be unclear and not worrying about it and moving on to something else.

DBYou mean you just take a break? Or you just end the painting?

LBNo, for example, if I start telling myself, “Oh, I should do . . . ” this or that, there’s this feeling of being bored and trapped that comes up, and it usually starts with my asking myself, “But what will people think?” That’s a full stop right there. I’ll just let whatever it is be what it was up until that point. Another description of how I work is that I’m getting something out, expelling something, and I want to look at it, but it can’t look back at me.

DBIf you saw their eyes, how would that change the gaze?

LBI’m not interested in a relationship with the figure. It’s about me being able to look at it, there’s no back and forth between us. I did decide to paint a face in a painting I’d just finished and it took weeks, it was very difficult to find a face that gave some agency to the figure but still wasn’t looking at me or sucking all the attention. I’m usually more interested in what emotions you can show with other things in your body than your face.

DBIt seems very precise, and enigmatic at the same time. You’ve talked about it in terms of voyeurism.

LBYes, exactly, voyeurism. You know how Tom of Finland takes this erotic subject, basically something he wants to jerk off to, but he puts so much work and attention into it? The work is perfectly made. He doesn’t just stop when the image fulfills its libidinal intention, he really sees it through. I like that.

DBSo do your paintings excite you?

LBYeah, at first, but they take so long that it wears off [laughs].

DBI know. I’m a very slow worker in my own life.

LBI like it when men, usually, get turned on, but when the fact that they get turned on is very disturbing to them.

DBThey get turned on by your paintings?

LBYeah.

DBIt sounds like that doesn’t feel like a violation to you?

LBI like it if they’re turned on—

DBBut disturbed [laughs]. That’s perfect.

LBIf they’re just turned on, that means they’re not getting it, I think.

DB[laughs] But you haven’t heard of women getting turned on by them?

LBOh absolutely, yes. But I would say, I’m not really making work to turn people on, it’s more a by-product of the feeling of being out of control, of humiliation.

DBShame is kind of cousins with masochism, right?

LBRight.

DBIn one of the many interviews with you that I read, you were talking about how you look at these figures with a nonjudgmental gaze, that that was important. Some of the interviewers seemed like they weren’t doing that.

LBTo me, these figures are always dignified, and I’m in no way being mean to them or making fun of what they’re engaged in. That’s important.

I’m also okay with that description—ugly, to me, isn’t really a bad quality. Maybe that’s also why the figures in the paintings aren’t looking at the viewer, so you can’t really shame them.

Louise Bonnet

DBWould you be able to talk about the influence of comic book artists and illustrators? Of course, since I’m in the Bay Area, I think of R. Crumb immediately—you’ve mentioned him in the past, and I’m curious about what in his comics drew you to them. They’re often read as really macho, guy things and it seems like you’re very much interested in this sort of female or feminine version of the body and embodiment.

LBBecause I grew up a bit isolated from pop culture, a lot of the political discourse that was going on in the ’80s wasn’t really reaching me. I felt a bit like an alien in life for a long time, and I didn’t completely understand all the subcurrents of the contemporary world. So when I saw those comics, probably in middle school in Switzerland—because Europe is more like the Bay Area, where comics like R. Crumb are celebrated more than, say, Superman—I think I understood them in maybe a naïve way, or at least in a personal way outside of the context where I now realize most people interpret them. I didn’t take it as, you know, the male gaze and being overpowered. To me it was more, Oh, you can draw a woman like that and she’s amazing and she’s a giant, she’s covered in hair—

DBThose women are really powerful, it’s true.

LBI wasn’t very enlightened.

DBAnd what does “enlightened” mean?

LBIt’s a realization that I’ve had later in life. When I was in Switzerland, I think I just accepted things as they were. If a woman was objectified, I didn’t see it as odd or unjust in the way I do now. It was just normal.

DBEven in Switzerland? I thought of it being very liberal there.

LBThere are pockets of progressive people, but the rest is . . . they’re pretty repressed. I went to art school in Switzerland and no one was gay.

DB[laughs] On the surface.

LBExactly. I’m sure the desire was there, but no one was out. It was very, very repressed.

DBSo Los Angeles must have seemed like—

LBOh, it was incredible. After two months I thought, I’m never going back.

DBThere are lots of places you could have gone. What made you come here?

LBReally only because I knew people, and I could stay with them. If they’d been in Oklahoma I would have gone there.

But so, yeah, I took art and comics at face value at that time—it was exciting, you could just do this or that with it. I didn’t fully get into the subtext of it until later.

DBI think people have to do a lot of relearning in order to have a different version of women’s relationship to reality. It sounds like you didn’t have to do some of that relearning because you didn’t really have it down in the first place.

LBI’m learning it all now, still. I always thought, Oh, what I’m doing isn’t political, or, I don’t have an agenda. And then I realized, I absolutely have one.

DBYeah, you absolutely do [laughs].

LBIt had to arrive on a stream of consciousness, shutting down a lot of overthinking.

DBTotally. Shutting off that censor can be the hardest part of working on a project. At least for me, with writing, I have to shut it off totally and just do these things I think are so crazy that nobody’s going to relate to them. And then, you know, this other part of the brain, the editing part of the brain, can come in. But it has to be under control or the editing part will get rid of everything that makes the piece alive.

LBRight. When I want to do something, I can see it, I sketch it really fast, and then I basically shut off and do it.

DBJust really enter that body.

Artwork © Louise Bonnet; photos: Jeff McLane

Louise Bonnet: Onslaught, Gagosian, Hong Kong, May 31–August 6, 2022