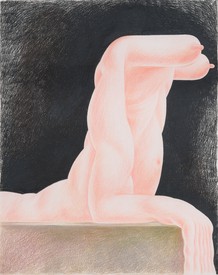

Through softly luminous portraits of bulging, distorted figures, Louise Bonnet probes the experience of what it means to inhabit a body. Her protagonists walk a line between beauty and ugliness, between absurdist, knockabout comedy and extreme psychological and physiological tension. Inhabiting sparse landscapes and boxed in by the edges of the canvas or the page, they act out dramas of profound discomfort that plumb the depths of the artist’s subconscious. Photo: Jeff McLane

Freja Harrell joined Gagosian, New York, in 2011, focusing on sales, developing exhibitions, and working closely with a number of the gallery’s artists.

Freja HarrellI remember you calling me after the Supreme Court draft opinion leaked, incensed and eager to do something in support of reproductive rights. Tell me more about what moved you to create the painting Red Study (2022), and your decision to donate the proceeds to Planned Parenthood.

Louise BonnetI wanted to do something tangibly helpful. And since I didn’t want to become an ACLU lawyer—or rather, I can’t—I thought at least I could make a painting, sell it, and give the proceeds to Planned Parenthood.

FHSo when you decided to make this painting, you came at it from that perspective? You wanted to make a work that dealt directly with these issues?

LBYes. It shows a woman who’s bleeding, but is in charge of what’s happening: she has agency and has made a decision. There’s blood, so it could be her period, a miscarriage, or an abortion, or indeed another medical situation—it’s ambiguous. She’s not victimized or—

FHStigmatized.

LBExactly. She knows her body and she’s in charge of it.

FHBans on abortion are connected to other aspects of reproductive freedom, like social structures and power arrangements of gender, race, class, religion, and immigration status. How do these themes of the body, control, and agency figure in your work generally? These topics seem to pervade your practice more broadly.

LBWomen’s bodily fluids, and women’s bodies in general, are controlled by men in a lot of ways.

FHAnd we pander to their gaze.

LBYes. Because we’re generally raised to think that’s our worth. The fact that other people can literally tell you how your body is supposed to work or not work is just so offensive. Blood plays a similar role here to the urine in my triptych—

FHYour painting, Pisser Triptych (2022) that was exhibited in the last Venice Biennale?

LBExactly. The act of urinating may be seen differently based on cultural constructs of gender. Generally speaking, it’s seen as sort of macho for a man to take his penis out and pee in public. By contrast, women have to hide. They are not allowed to leak and if they bleed, it’s to be hidden—it’s regarded as disgusting.

FHRight. And similarly, if a man is bleeding publicly, the cultural assumption would be that he had gotten into a fight. It’s glorified. The result of an act of dominance.

LBAnd heterosexual men are biologically attracted to women when they are fertile and fertility involves bleeding. And yet, it’s not meant to be seen.

FHRed Study is obviously very bold. Do you feel that putting these issues front and center, showing a woman in her power while bleeding, can make people more aware of the stigmas around this? Does art have that power?

LBI think it’s important to make public statements when it comes to sending a message about basic human rights. It’s vital to name things—not to choose a vague or poetic word for abortion and blood. No one wants to have an abortion—it’s a very difficult thing to live through. Not to trust women to make that choice for themselves is oppression. So I wanted the work itself not to skirt around the topic or pretend that women aren’t talking about what happens to them and their bodies. I want to actually talk about it directly.

FHBe explicit about the subject matter.

LBYes. And it doesn’t have to be pleasant, because it’s not.

FHSo if we look at Red Study, the female figure’s stance really conveys power. She’s bold and confident, almost defiant, feet firmly planted and moving forward. She appears to be in control, but at the same time, her hand is digging into the flesh of her hip—a gesture that conveys angst or pain.

LBExactly—it hurts, and it’s scary and sad. But all these emotions don’t mean you’re a victim, or that you shouldn’t be in charge of your decisions, or should have to hide.

FHAnd it’s complicated—you can be feeling all these emotions at once. I think it’s interesting where you’ve looked to for inspiration, including at a lot of medieval art.

LBIn a lot of medieval art, urine can be like a blessing—for example, an angel urinating on a woman to bring good luck getting pregnant. I found an image where a woman, maybe the Virgin Mary, is floating in the sky with rays of light coming out of her vagina, and a bunch of knights are kneeling on the ground beneath her, their faces upturned, receiving the light.

FHTo partake in the glory, in a way.

LBYes—it doesn’t seem to be urine, but rather glory. Some sort of halo or something. This is definitely not the way this subject would be portrayed now.

FHThe conical structure in Red Study is interesting, because you can hardly call it a stream: It almost feels like a divine light emanating from within her body. You’ve also talked about how you can’t be certain if it’s coming out or going in.

LBYes—it looks as if it could be painful, but also could perhaps be providing a kind of release. Really it’s about not having to pretend or hide.

FHIt’s almost like a third leg.

In many of your paintings, the figure is confined within a tight space. What were your thoughts about composition in relation to this theme?

LBI usually play with claustrophobic framing. In this instance, the terrible feeling wrapped up in the Supreme Court decision is that they’re trapping people. Trapping them in their own bodies, in their own lives. The composition makes the woman look gigantic; I wanted her to look monumental.

FHYour work obviously carries surreal undertones. Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) talked about how Surrealism allowed her to communicate female desires and the female experience in a way that she couldn’t really do through other modes of art. Is this something that resonates with you?

LBYes, that you have to create a world that doesn’t exist—

FHAn inner world.

LBYes, it’s an inner world and perhaps in Carrington’s time, you had to use Surrealism to be allowed to depict that world. Now, I don’t think I have to be as secretive. But on the other hand, it feels surreal that we have to fight again for long-held human rights.

It’s vital to name things—not to choose a vague or poetic word for abortion and blood. . . . So I wanted the work itself not to skirt around the topic.

Louise Bonnet

FHAre there any artists or creators in general—writers, perhaps, or filmmakers—who influenced you when you were creating this painting?

LBFor this one specifically, I was looking at Japanese woodblock prints. They provide a kind of rigid architecture that makes it feel safe to enclose the craziness happening in the scene—like a set.

FHIt’s a little filmic in that sense.

LBYes. I also looked to Paula Rego (1935–2022), who made a series of paintings depicting abortions. They’re unbelievable. The body language of the women is unmistakable. There’s no trying to veil it, even though the women’s faces are pretty passive. They are shown on beds, some lying, some with their knees up and legs apart, and you feel everything through their bodies and their positions.

FHSo you were thinking about the way Rego uses the body to express emotion?

LBYes. And the hands. There is one work where a woman looks like she’s holding another person, but then you realize her fingers are not actually touching them.

FHAnd it was during your recent visit to Venice that you saw Rego’s work in person for the first time?

LBYes. I hadn’t understood how amazing it was until then. I was totally floored. She really conveys all these feelings through the body and not the face.

FHMaybe that’s really what this is all about: expressing the feelings of an inner world in ways that other women can relate to, but many men perhaps can’t.

LBYes, I wonder what [Supreme Court Justice] Samuel Alito would think Rego’s women are doing.

FHBecause they’re not explicit.

LBMaybe he’d think they’re praying for him.

Artwork © Louise Bonnet; photos: Jeff McLane

Learn more and donate to Planned Parenthood.