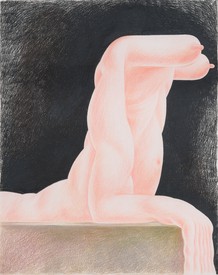

Through softly luminous portraits of bulging, distorted figures, Louise Bonnet probes the experience of what it means to inhabit a body. Her protagonists walk a line between beauty and ugliness, between absurdist, knockabout comedy and extreme psychological and physiological tension. Inhabiting sparse landscapes and boxed in by the edges of the canvas or the page, they act out dramas of profound discomfort that plumb the depths of the artist’s subconscious. Photo: Jeff McLane

Naomi Fry is a staff writer at The New Yorker, where she writes about culture in its various forms.

Naomi FryI just rewatched The Brood a couple of weeks ago. When curating your selection of movies, what was it about this film that attracted you vis-à-vis your art and your interests?

Louise BonnetIt was the first film that I knew had to be included, because it touches on so many things I’m familiar with. Canada at that time looked a lot like Switzerland, where I grew up, and then the clothes, the cult around this male psychiatrist figure, the rage—the manifesting of rage really touched something. The fact that Cronenberg can depict these things without being sloppy or too emotional—even though actually it is emotional—really speaks to me.

NFI probably watched The Brood for the first time as a teenager. Seeing the film now, it struck me that aesthetically it’s fantastic. The compositions are so beautiful. It’s an interesting combination of a completely gorgeous arrangement and a very unpleasant, you know—

LBAlmost everything else. [Laughter.]

NFAlmost everything else, right? As a painter who portrays distended, engorged, uncomfortable bodies, but in beautiful, very large-scale tableaux, is that something that resonated for you in any way?

LBYes, I think that what I took from it—and also from Dead Ringers [1988], which I love—is Cronenberg’s seriousness. He’s not making fun of his characters; he’s taking the grotesquerie and the rage and the insanity seriously in an intellectual way. I try to do this as well, depicting peeing and bleeding in my paintings as dignified and important.

NFIn a previous conversation we had for Cultured magazine online, we spoke about periods and mammograms and all of these things that are given some space in this movie. But The Brood is arguably not done from a feminine perspective. Cronenberg’s a male filmmaker. I’m wondering if you feel that the work you do is connected to your subjectivity as a woman? Do you feel like these questions about body horror touch you from that angle?

LBYes. But for a long time I didn’t think that it had anything to do with that. My work had nothing to do with any sort of pointed messaging.

NFBecause it’s embarrassing, in a way, right? You don’t want to be corny about it—

LBRight. I don’t want to be scold-y or—

NFYou don’t want to overburden it with a kind of second-wave feminism.

LBIt’s truly this: if you’re yelling, no one can hear you. But then I realized, Actually, this is all I want to talk about. I think I’m just trying to do it in a way that’s visible and that people can hear without feeling berated to the point of tuning out. But I do think being extremely uncomfortable and thrown off-balance is very interesting.

I think I see everything as a movie screen. When I paint, in a way, I’m painting scenes from a movie.

Louise Bonnet

NFAs an artist or as a viewer?

LBFor a viewer. Cronenberg makes everything look great, and you feel terrible, but you can’t blame him for it because he’s just showing you something and you can see it because he paid attention to it. With Dead Ringers—I mean, I have a daughter who’s seventeen and she hates anything I show her—

NFBecause she thinks you’re trying to teach her something?

LBWell, there’s that, and also that it’s sexist—things I never even thought were sexist.

NFOh, it’s not progressive enough—

LBYeah, she’s offended. Sorry. [Laughter.] So I showed her Dead Ringers, thinking she was going to leave the room, but it really holds up. She liked it; she really got it. That’s a rare thing, actually, because it’s old.

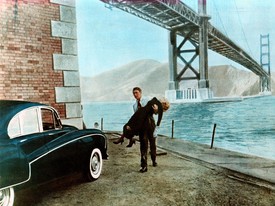

NFYeah, at this point it’s old, which is terrifying to admit, right? In general, with selecting the movies for this series, including All That Jazz, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Under the Skin, and Kung-Fu Master!, among others, what bound your selections together? They all have to do with the body being unwieldy or seeking to regain control in some way, but the particular movies that you selected, what called to you about them?

LBThat’s true: in all of them the character is out of control in some way, but there’s always an expected element—they’re trying to gain control of something and it’s a bit unclear. I know that A.I. [Steven Spielberg, 2001] is a bit of a controversial choice. I remember the first time I saw it, it made me so angry I got out of the theater and I yelled—

NFWhy were you angry?

LBBecause it pulled these emotional strings that seemed so obvious to pull and I felt manipulated.

NFBecause it was Spielbergian, commercial?

LBYes, exactly. But I never forgot it. And then I kept watching it, and it had to be Spielberg doing it, I think, because he can pull those strings. And it’s such a raw, basic message. It doesn’t let go at all, ever. Not at all.

NFRight, it sort of hits the nail on the head repeatedly for two hours.

LBWhich is really pretty rare.

NFYeah, I mean, props. [Laughter.] I have a friend who’s a painter who a couple of days ago said to me, “I can’t watch a movie through. The way I approach my work and the way I think about things, it’s very hard for me to have a drawn-out narrative presented in front of me for two and a half hours.” It was an interesting perspective that I hadn’t expected to hear from her. For you—as a painter who is affected by cinema, by movies—do these two mediums exist in tandem?

LBI think I see everything as a movie screen. When I paint, in a way, I’m painting scenes from a movie.

NFBecause they’re scenic and grand in size?

LBIt’s true that I like that you can stand in front of my paintings and not see the edges. I like to hang them low so you’re in them. And the framing definitely comes from movies. There’s also a narrative in each of the works. I don’t know what it is, even, really, but the images are picked from my head and painted as scenes from movies.

I didn’t have a TV when I was growing up, which ruined me in a lot of ways. And when I would go to the movie theater, it would be so unbelievably overwhelming and shocking, because there was no ramp-up. We would almost never go. When we did, we would go and see films like—remember that Disney cat-from-space movie?

NFCat from space?

LBTruly, I remember one of the first movies I ever encountered, which floored me, was the story of a cat—

NFAnimated?

LBNo, I think it was live action.

NFDoes anyone here know what this is?

Audience memberThe Cat from Outer Space [Norman Tokar, 1978], I think.

NFIs it literally called The Cat from Space?

LBYes!

NFOkay, now I have to seek this out.

Through all these movies, the idea of the viewer feeling what is happening onscreen in their bodies rather than necessarily in their minds is part of the intent and significance.

Naomi Fry

LBNo, you don’t. [Laughter.] But when I saw it, I was like, Oh my God. I’m basically still floored by movies, more than almost any other art form. I see almost everything through that lens. But I don’t like people [laughs], so I could not make a movie.

NFBecause that’s a very different thing, right? You act alone versus having to collaborate with a trillion people. That always seems like a nightmare to me.

LBWriting is probably the same, right?

NFYeah, totally. I don’t want to work with anyone. [Laughter.]

LBSo I found the next best thing, in a way.

NFI was interested in your selection of All That Jazz [Bob Fosse, 1979] as part of the body horror canon. I think I can see why you chose it, but it’s not an immediately obvious choice.

LBI’m not an athletic person, so seeing anyone who can do things with their body that way is amazing to me. I also love workplace minutia more than anything.

NFThat’s so interesting, because you were just like, I hate people, I don’t want to work with others—

LBI want to look at it, I don’t want to be part of it at all.

NFYou just want to see people having tiffs and—

LBRight. And the characters in All That Jazz are dancing, so I can’t be jealous in any way because I couldn’t do it at all. I can fully look at it without feeling—

NFCompetitive in any way—

LBYes. Between the dancing and the fact that the main character is dying—I’ve had so many panic attacks about dying, you know, as one does, I guess—

NFAs one does, yeah.

LBIt’s done in such a way that it made me feel better. I think all these movies, in a weird way, are sort of life-affirming for me. Even The Brood.

NFHow is The Brood life-affirming?

LBI think it provides a letting go, as bad as it is. The rage is out there.

NFSomething is happening and not being repressed.

LBYes. The most subversive film in the group is Kung-Fu Master! [Agnès Varda, 1988]. I don’t think it could be made now. Basically, Agnès Varda put her own son in the movie. And the story of the movie is that the woman played by Jane Birkin has an affair with the teenager played by Varda’s son.

NFHow old is his character?

LBFourteen.

NFOh. Oh, Agnès Varda. [Laughter.]

LBIt’s unclear if anything is really happening. Still, it’s extremely shocking. But so subtle. And Jane Birkin’s character is having this whole midlife crisis—again, with her body and everything—

NFOf course.

LBAlso, it seems like they’re all basically playing themselves. I’m sure it’s just because they’re good actors. It’s very, very disturbing, but also so empathetic.

NFThis you put in the category of the failure of the middle-aged female body—to be ruled by something your body is doing, being older and making choices, clearly physical choices, that are so crazy. As you said, the way Agnès Varda deals with things is at once subtle and very shocking—more so, I think, than The Brood, really.

Through all these movies, the idea of the viewer feeling what is happening onscreen in their bodies rather than necessarily in their minds is part of the intent and significance of the films, right? That you’re kind of jolted physically?

LBExactly.

NFYou feel gooey and meaty and all of these things that you don’t usually feel in everyday life.

LBWell, you try not to.

NFYou’re consistently resisting that, in fact. And these movies bring you back to that state.

LBYes. Back to the body. A visceral response, to me, is the most powerful.