Alexander Wolf is a director at Gagosian in New York. Since 2013, his projects at the gallery have included exhibitions, communications, and online initiatives. He has written for the Quarterly on Piero Golia, Nam June Paik, Robert Therrien, and other gallery artists.

Robert Therrien’s home and studio fill a two-story, fifty-foot-wide concrete building in an industrial section of Los Angeles not far from the University of Southern California. The first floor is a workshop whose orange-painted plywood walls are dotted with flattened objects made of wood and sheet metal: sculptural sketches of bows, pitchers, snowmen, and other familiar things. Many of these images were originally adapted from plastic stencils that Therrien used as a boy to learn how to draw.

Therrien’s enduring yet constantly evolving subjects—which also include mirrorlike ovals, oil cans, church steeples, coffins, and tambourines—tend to hold some personal significance. The mirror, for example, is “a female image, my mother”; the snowman is “the closest to a human figure, myself or a man.”1 But for Therrien the key test is the extent of an image’s familiarity to others, even if perceptions diverge. (Is a bent-cone shape a witch’s hat or a chess piece?) His snowman—reduced to three overlapping spheres—may derive from the snowy Chicago winters of his youth, but any narrative dimension depends on what the form conjures in the eyes of the viewer: it’s all perspective. (Turned on its side, the snowman becomes a bulging storm cloud.) Other muses include kitchenware, furniture, the studio itself, and Therrien’s apartment in the same building. His tendency to use what is most immediate to him makes one wonder which among these rooms and their furnishings might serve as his next subject.

The studio was designed to Therrien’s specifications in 1989. It is divided into eight spaces, four downstairs and four up, each approximating the dimensions of the one-room studio he worked in before constructing this one: a room on Pico Boulevard of about 30 by 22 feet, dimensions he had grown accustomed to, having worked there since 1972.2 Tellingly, he also divided his first museum exhibition—in 1984, at LA’s then nascent Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA)—into six rooms of this size. As Heather Pesanti, who curated an exhibition of Therrien’s work at The Contemporary Austin in 2015, observes, “The Pico studio has left an indelible physical and psychological imprint on the artist’s life, functioning as both the underlying plan for his workspace and a psychic current driving the work and rooms that have emerged from his studio walls.”3

A wide staircase leads to a large, bright, gallery-like space with white enamel floors, which Therrien uses in part to consider how his sculptures will appear in galleries and museums. (A precarious stack of giant plates, modeled on the artist’s own kitchen plates, is currently the first sculpture visitors see upon entering the Broad in Los Angeles. In an imposing trick of the eye, the plates can seem to quiver as one walks around them, even giving vertigo on occasion.) One section of the space is currently dominated by a massive shipping crate whose interior is a freshly painted white room. In a handful of recent works, Therrien has used these freestanding rooms as the spatial equivalent of blank canvases, enabling him to posit objects and architectural elements as the subjects of still, carefully staged scenes: a wood-paneled office, furnished only with a stack of tambourines and a ladder to an escape hatch, or a vertiginous corridor leading to a pair of emergency doors. These contained environments are the latest and largest results of what Therrien has called his ongoing “figure-ground play.” No title (room, pants with tambourines) (2014–15), for example, also features a stack of tambourines in the foreground, and what appears to be a pair of pants—they are in fact painted cardboard—hung on the far wall. The work derives from an earlier photocollage, a composition that Therrien has transcribed seamlessly from two to three dimensions, but for one change: in the original the background element is a coffin, which bears an eerie resemblance to the trousers that have replaced it. This investigation of the relationship between objects and space is also evident in Therrien’s drawn images, which almost always hover in the center of the page, and in his early wall-mounted sculptures, which appear to recede into the wall.

Therrien’s tendency to use what is most immediate to him makes one wonder which among these rooms and their furnishings might serve as his next subject.

Alexander Wolf

This kind of spatial ambiguity—parallel to dramatic fluctuations of scale—has informed Therrien’s art since some of his first engagements with large exhibition spaces, in which he altered existing architecture to achieve more abstruse settings. (He also seems to prefer such indeterminate conditions in daily life. He has said of living in Los Angeles, “You’re in a large metropolitan area but it seems small because you can’t see very far due to the smog. This is psychologically more comfortable.”) The shipping-crate rooms give him a way to explore how his images exist in space within individual works. As with any sculpture, one must walk around them, especially since the interior elements sometimes transcend the frame of the room, continuing onto the exterior walls. To observe them in a gallery is to drift between the real world and the corners of Therrien’s imagination.

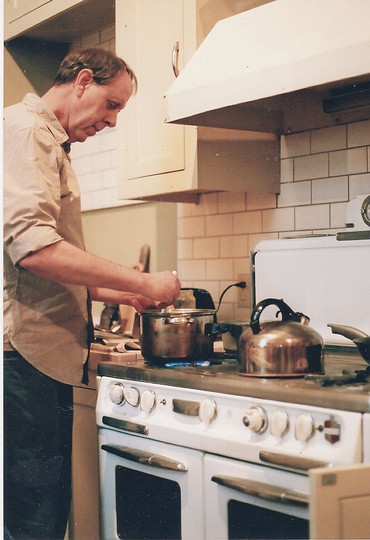

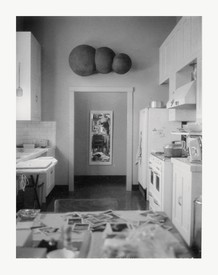

A door in a corner of Therrien’s studio leads to his apartment, where beige-painted walls and brown linoleum flooring feature throughout. The pink-and-white-tiled kitchen is like a stage set, with a great chasm between the tops of its metal cabinets and the soaring ceiling. There are also a spartan bedroom, a bathroom, and an office area with a walk-in closet packed with vinyl LP’s, tape cassettes, and CDs. Adjoining the kitchen is a space called “the other room,” an in-between area with a wooden table and four chairs that were made famous when Therrien replicated them at three and three-fifths times their size, a towering example of his ability to adapt the most immediate things to supernatural effect. These often include furnishings that could be described as standard or ubiquitous, heightening the surreal impression when they shift in scale.

Beginning in 2012, Therrien and his two-person studio team began to meticulously replicate the many two- and three-dimensional contents of a wall in this “other room.” Using these copies, they made a mirror image of the wall on its other side—an interior wall of the studio—including facsimiles of the several photographs and drawings that were pinned to it at the time, as well as carefully mapped pinholes and cabinetry. Later, visitors to the exhibition at The Contemporary Austin experienced the wall as an image, or collection of images, on the far wall of a freestanding room—complete with beige paint color and brown linoleum floor—to be observed but not entered. Walking around the sculpture, titled No title (room, the other room) (2012–14), one saw the wall’s uncanny reflection on its back.

Therrien has used these freestanding rooms as the spatial equivalent of blank canvases, enabling him to posit objects and architectural elements as the subjects of still, carefully staged scenes.

Alexander Wolf

When Therrien’s building was close to completion, he was told that it would need an indoor dumpster to be up to code. A small room, no larger than a walk-in closet, was constructed beneath the staircase for the purpose.4 The room is accessed by a set of dutch doors, a feature of Therrien’s grandparents’ house during his childhood and a recurring subject in his artmaking. For Therrien, the independently swinging top and bottom halves of the doors “represent a sort of balance.” Space for him is an active presence that he manipulates to explore questions related to perception and perspective. And in the end this tucked-away closet—a nook better suited to certain intimate projects than any other area in the vast studio—has, like all other facets of the space, had a higher calling. Curator and art historian Margit Rowell, who organized an important exhibition of Therrien’s work at Madrid’s Reina Sofía in 1991–92 (among several other Therrien projects), wrote in 2007,

On my first visit to Therrien’s studio in the late 1980s, he showed me a room under the stairs that was a very private, even magical place. I remember that this is where I first saw the plastic stencils, which surprised me. Also, in this Ali Baba’s cave, I found Kodak boxes filled with small torn-out newspaper illustrations, cut-out comic book characters, and fragments of Therrien’s own drawings. The small, rectangular room was relatively empty, and I remember saying to myself: “Here is Bob’s real universe; here is where everything begins.”5

As an artist whose primary subject is the slippery nature of perception, Therrien is especially involved in the matter of how his work is seen. In particular he seems to have sought specific settings for exhibitions of his early wall-mounted sculptures, which, seen together, gave the impression of amply spaced pops of primary color in otherwise white rooms.6 Following the precisely scaled galleries he created for his 1984 exhibition at MoCA’s Temporary Contemporary, he made a rotating exhibition of such works at Leo Castelli’s New York gallery in 1986–87, sometimes forgoing the main gallery spaces for a more intimate basement.7

Therrien’s engagement with exhibition space evolved into sculptural/architectural interventions that presaged his most recent room works. In 1992, for documenta IX, he covered the walls of an attic space at Kassel’s Museum Fridericianum with sections of cardboard painted white, creating an ambiguous space into which he inserted subtle visual notes, mounting a cabinet of matching white on one wall and applying three tiny cutouts of bluebirds to another.8 That same year, at the Angles Gallery in Santa Monica, he used wood and cardboard to create Bench Room, a work of multiple levels holding long bright-red benches: a transient meeting place that enabled awkward interactions.9

Simultaneously, Therrien’s elegantly pared-down representations of objects gave way to increasingly realistic representations of tables, chairs, kitchenware, and other items, often greatly enlarged. He now replicated familiar things at multiples of their actual scale, with a level of precision that invited viewers to suspend their own disbelief. Photography was key to the success of these works: Therrien took hundreds of Polaroids from underneath his kitchen table (a wooden Gunlocke model), assuming the perspective of a small child to capture its undersides and legs, as well as four matching chairs (and the feet of various guests).10 The images would serve as the basis for Under the Table (1994), the nearly four-times-larger replica—an adult can stand underneath each piece of furniture.

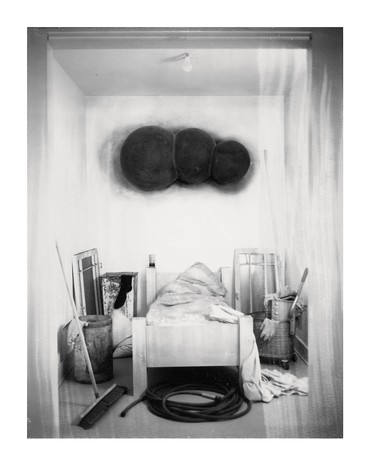

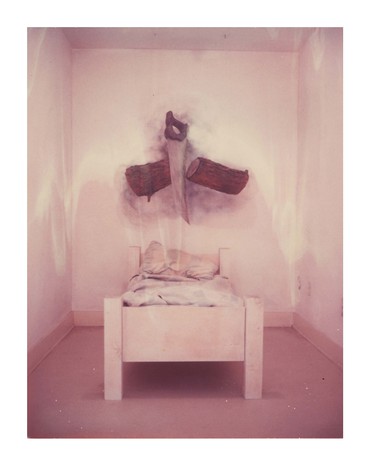

These two practices—the alteration and staging of spaces, and the use of photography as a drafting tool—merge in many more black and white Polaroids that Therrien shot in the room under the stairs and elsewhere in the studio. In 1995, he collaborated with the art critic and poet John Yau on Dream Hospital, a limited-edition book comprising a text by Yau and photogravures made from eight such Polaroids.11 The cover image was shot from the room’s entrance—as if gazing through a keyhole, or in this case perhaps between the dutch doors—and the ceiling, walls, and floor serve as built-in framing elements. Above a shabbily made-up wooden bed is a cartoonish apparition of a saw cutting through a log. Here Therrien plays upon photography’s supposed veracity, levitating self-possessed objects in a modest bedroom (the image clearly anticipates the surreal stagings in the freestanding rooms). Other photographed yet unlikely scenes include flying beards, tangles of phones and wires whirling through the air, and running barbeques. These impossible images are closely linked to the equally impossible sculptures, which sometimes appear in the photographs, and at other times are triggered by them.

Alike objects congregate in various corners of Therrien’s studio—here a few old Cosco high chairs, there a group of long-spouted oilcans, and many molds and stencils for his recurring images. One day around 2000, Therrien received several red-plastic-mold samples in the mail. Over time, the molds attracted other red objects: red sneakers, crayons, fake bricks, fake strawberries. At some point the collection was moved to the room under the stairs, where it continued to grow—a red gas lamp, a red quesadilla grill, a red kilt appropriated by a friend from her old Catholic-school uniform. Therrien imagined that a red-haired family might live in the room. Its contents were mostly found, but included some objects the artist made: an egg carton, for example, held large red-plastic drops. (He has also made stainless steel drops the size of rugby balls.) By 2007 the collection had grown to 888 objects, making the room no longer enterable.12 Since that year, the objects have been shipped and reinstalled for exhibitions at Gagosian New York and at Tate Britain, which now owns the work in partnership with the National Galleries of Scotland.

The departure of this collection, which came to be known as Red Room, left the room under the stairs vacant, available to Therrien for new projects . . . or for storage. One recent morning it was filled to the brim by two floor-to-ceiling stacks of massive Revereware pots and pans, like the kitchen cabinet of an untidy giant. But within Therrien’s studio, where one struggles to grasp the expansive, constantly changing spaces and the familiar but curiously large objects within them, it was easy to imagine that I was in fact small, and the pots and pans were just as they should be.

1All quotes from Robert Therrien are from Margit Rowell’s interview with him in Robert Therrien, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1991).

2The dimensions of Therrien’s former studio were confirmed in an email from Therrien to the author, July 31, 2017.

3Heather Pesanti, “Robert Therrien,” The Contemporary Austin, 2015. Available online at www.thecontemporaryaustin.org/exhibitions/robert-therrien/ (accessed August 2, 2017).

4Therrien described the impetus for the closet to the author during a studio visit on June 5, 2017.

5Rowell, Robert Therrien, exh. cat. (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2008), p. 33.

6Ibid., p. 24.

7Maureen Mahony, a consultant who has worked closely with Therrien ever since she organized several exhibitions of his work at the Leo Castelli Gallery during her tenure there, discussed Therrien’s Castelli exhibitions, studios, and room-related works with the author on May 23, 2017.

8See Gregory Salzman, Robert Therrien Polaroids and Drawings, exh. cat. (Santa Fe: site Santa Fe, and Toronto: York University Art Gallery, 2000).

9Mahony, conversation with the author.

10Ibid.

11Therrien and John Yau, Dream Hospital (Santa Monica: Jacob Samuel, 1995).

12See Rowell, Robert Therrien (Gagosian), pp. 33–34.

Artwork © 2017 Robert Therrien/Artists Rights Society/ARS, NY