An architect and a historian, Jean-Louis Cohen holds a chair at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts and one at the Collège de France. His forty books include Architecture in Uniform (2011), The Future of Architecture since 1889: A Worldwide History (2012), and Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes (2013).

The designs of Frank Gehry, one of the most innovative architects working today, grace numerous metropolitan skylines around the world. Known for their deconstructivist approach and creative use of materials, his buildings incorporate a wealth of textures that lend a sense of movement to his dynamic structures. Gehry is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including the Pritzker Architecture Prize (1989) and the US Presidential Medal of Freedom (2016). Photo: © Alexandra Cabri

Rani Singh is director of special projects at Gagosian, Beverly Hills. Her work focuses on strategic planning and legacy management for artists, exhibitions development, museum outreach, and programming.

Frank Gehry: Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings, Volume One, 1954–1978, the first of eight planned volumes, is more than a catalogue of Gehry’s drawings. It’s an opportunity to see the evolution of his vision, exemplified by the medium that has remained paramount in his creative process: drawing. To this day, Gehry’s sketches and drawings are critical to his architectural concepts. They are, for him, “the process to get to an idea.” Produced under the direction of Staffan Ahrenberg, publisher of Cahiers d’Art, and edited by architectural historian Jean-Louis Cohen, the catalogue raisonné gives us a comprehensive view of the work that defines one of the most expressive architects of our time. In an industry where the final product is reliant on many hands and machines, Gehry’s drawings are an intimate peek into his creative process.

—Rani Singh

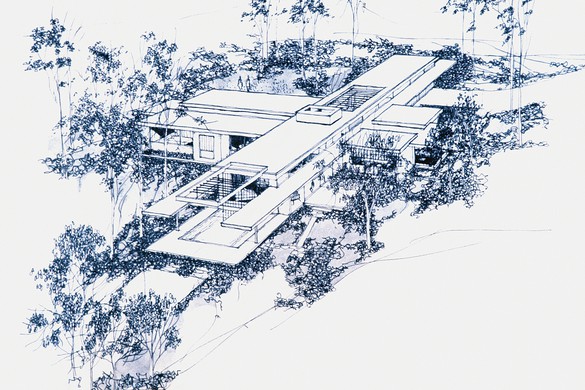

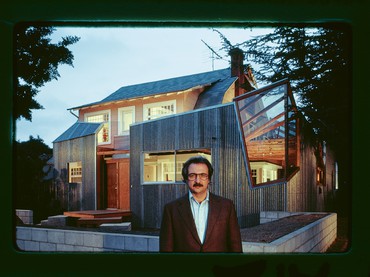

Jean-Louis CohenFrank, we’ve been in conversation for forty years, since I first came to see you in your wonderful house, which is the highlight of this volume. This is a particular book in the realm of books about architecture. There are lots of oeuvres complètes, complete works, out there, but they’re usually filled with photographs of buildings and final plans. This book is about the process—or, I should say, it’s about two processes. The first, of course, is the design process: how buildings are imagined, developed, and finally built, or remain unbuilt. The second is the process of your development as an architect: the process that took you from the late 1950s, and the Steeves House in Bel Air, to your own house in Santa Monica in 1978. What we see in the book, through a series of seventy-five built or unbuilt designs, is the process that led you to become Gehry, that put you on the map, ending with your house, which completely redefined the discipline of architecture. So it’s a curtain opening in terms of the full catalogue raisonné, and it’s of course a curtain opening in terms of your work.

My first question is about this period of your life. How easy was it to become the architect you wanted to be in Los Angeles during that time?

Frank GehryI had no clue who I wanted to be. The Santa Monica house was circumstantial: we were going to have a child, Berta and I, and we needed to move out of an apartment. My mother convinced Berta to go out and find a house because I would never do it. So Berta bought a house, and I looked at it and said, “Well, we’ve got to do something.” I kind of liked the idea of building a new house around the old house and having them both exist and talk to each other. That was the idea. We didn’t have much money so we built it on a shoestring, and it leaked [laughter], and a lot of other things. Anyway, there it was. We fixed the leak.

But the neighbor across the road came over to me and said, “What are you doing here? You’re ruining our neighborhood” [laughs]. And I looked at him and said, “Well, your house has a chain-link fence in the backyard, right?” He said yes. And I said, “So I’m just building in the spirit that you set.”

JLCBut it took you some time to arrive there.

FGWell, like everything else, it’s intuitive, right? I didn’t plan to disrupt the neighborhood. I was interested in asking could it be raw like that and could we still find some comfort in it, could it still be comfortable to live in. And it was cheap [laughs]. I was inspired by a lot of people.

JLCYes, this is one of the most fascinating aspects in these years. You meet artists, you build for artists. I’m thinking of important structures that are in the book, like the Danziger Studio and Residence [for graphic designer Louis Danziger, Los Angeles, 1963–65], like the Davis Residence and Studio [for artist Ronald Davis, Malibu, 1972]. And you installed the works of artists, particularly at LACMA [the Los Angeles County Museum of Art], beginning with the [Billy Al] Bengston show in 1968. Can you say something about your relationship with the LA art scene of those years?

FGSo, I was a truck driver. I went to night school. I took a class in ceramics. The ceramics teacher—it was Glen Lukens, the great ceramist—said he was building a house by Raphael Soriano. He took me to see the house. There was Soriano in a beret, all in black, telling the guys how to put the beams in the house, big steel beams. The next day in class, Lukens came over to me and said, “You aren’t going to make it in ceramics but you really looked excited about architecture.” So he enrolled me in a night class in architecture. And that’s how it started.

The Danziger building attracted a lot of funny people. Ed Moses—who I became friends with later—was on the construction site regularly, watching the building go up. He brought Kenny Price once, and he brought Bengston—I forget who else, but they all kind of started talking to me, inviting me into their social world, and it felt much more comfortable than what my architectural peers were doing in LA. To those peers the Danziger building was an affront to architecture.

I like the idea of a collaborative client/architect relationship where something unpredictable grows. . . . It doesn’t come from any rules.

Frank Gehry

JLCBut it was the only contemporary building reproduced in Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles book [Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies] of 1971.

FGYeah. When Banham called me, I didn’t take the call and I refused to have him come to see it. I told him it was my first building and I wasn’t ready for prime time [laughs]. They published it anyway.

JLCCan you say something about the early practice of installation in your work? Beginning with the Bengston show, where you installed sheets of corrugated steel and half-painted plywood, there’s something that appears first in the museum gallery and then leaks out to the street.

FG It’s hard to relive that installation. By that time Billy and I were friends, so he asked me to do this show. The director of lacma, Ken Donahue, and [the curator] Maurice Tuchman, who was there—they didn’t have a big budget and they were worried that I was going to go out and buy raw plywood and corrugated metal and they said they didn’t want that. So I went down to their storage room and there was a bunch of painted plywood there that had been used in a previous show. So I used that.

Then I got the guy from the Hollywood Wax Museum, Spoony Singh, to come over, and I said, “Can you make an image of Billy Al?” So we made Billy Al with his head and all the stuff. Billy Al was a motorcycle rider, so I borrowed his motorcycle-racing outfit. We got a motorcycle. And that was the entry to the show.

JLCThe Davis house is another pivotal project that connects you with an artist. It was published in Architectural Record under the title “The Search for a ‘No Rules’ Architecture,” a phrase that was one of your statements and your first slogan in the mid-1970s: “no-rules architecture.” Can you return to the Malibu intrigue?

FG[Laughs] Yeah. So in the profession of architecture there are all these little enclaves. New York had one, and at Princeton they were having a lot of high-level philosophical discussions about what architecture was. If your work didn’t fit into that, you were no one. And I couldn’t fit into it. I mean, I’d studied art history, I knew what they were alluding to, but it didn’t make it for me.

I think my relationship to the LA artists was a big factor: it was a comfort zone. I didn’t have to explain myself and they were very supportive. I felt like I wasn’t screaming in the wilderness. So I just never bothered to meet with the architects—I was kind of interested, but not really.

JLCYour projects with artists are probably the most poetic statements of that period of your work, but I think it’s also interesting to see you operating with other programs, among them commercial programs—the stores you designed for J. Magnin, for example, where you experimented with light, with acoustics, with interiors, with ideas that would later filter into your museum projects. This probably goes back to your early years working with Victor Gruen in the 1950s, designing supermarkets and shops.

FGWell, when you design a shop, you have to design a place where they’re going to sell stuff; that’s the reason they’re going to build the room. I think there’s a respect for the client’s needs. I’ve never had a problem with that. I like the idea of a collaborative client/architect relationship where something unpredictable grows out of that relationship. It doesn’t come from any rules. The project has to meet a budget, it has to be safe to go into—you have to meet all those criteria. But then what? And the “then what” is the interesting thing.

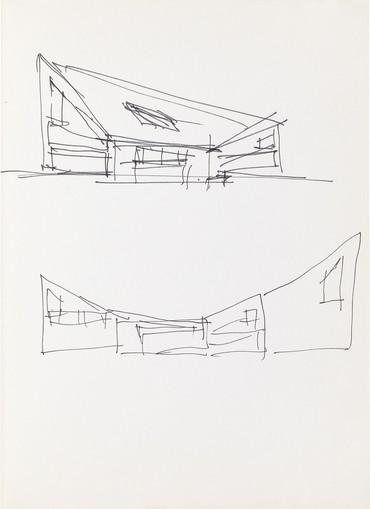

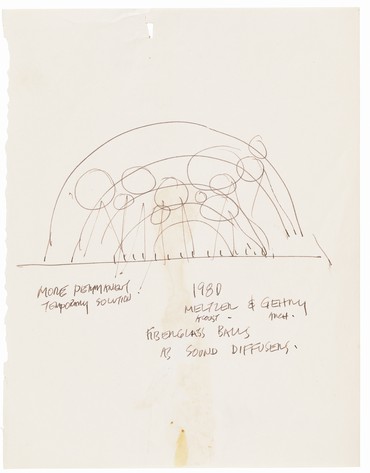

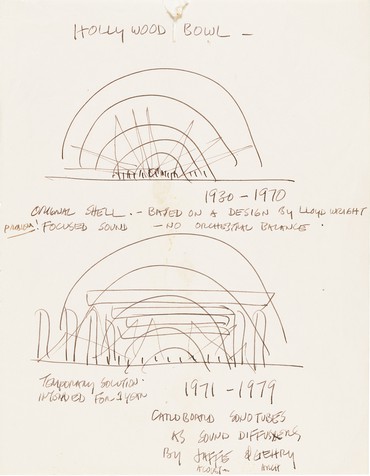

JLCOther projects of that period are also foundational to me. You’ve worked on major music projects; you’re currently working on a new building for the Colburn School in downtown LA. What’s striking is your engagement with spaces for music in these early years: the Hollywood Bowl [1969–76], the Merriweather Post Pavilion of Music [Columbia, Maryland, 1967], the Performing Arts Pavilion [Concord, California, 1971–75]. Was it already important in your life at that time?

FGWell, yeah, my family name was Goldberg, and Bach created the Goldberg Variations [laughter]. I was born in Toronto and Glenn Gould was playing them. In my high school I was responsible for a graduation event, and I got Oscar Peterson, who was nineteen at the time, to come and play for it. I was into jazz. I used to go to classical concerts—my mother took me from when I was a kid.

The music projects were circumstantial, though. The Concord Pavilion called and asked me to do it. They had a jazz drummer, Louie Bellson. I met him and that gave me the energy to work on it.

JLCYou also worked with acousticians, as you do now with Yasuhisa Toyota. That’s been a major aspect of your work, trusting competent people who bring you additional knowledge and expertise, and it was already present in your early work.

FGErnest Fleischmann, who was the director of the LA Philharmonic, opened all the doors to exploration.

JLC And the connection started at the Hollywood Bowl.

FGYeah.

JLCYou were alert to music, you were alert to the arts and engaging in the art scene—but there’s very little in your writings about cinema. Is it an art form you’ve ignored or don’t want to address?

FGThe great thing about cinema for me when I was starting out was that it was like a protective cover. The East Coast thought of LA as Hollywood, so all of us worked under the radar. Nobody cared that much. And it was very, very good, I think, for all of us.

JLCSo it was a self-conscious attitude in respect to LA—

FgI knew a few famous movie stars, some of whom I befriended, but it was never about that. The ones I met were more artists and really interested in the art world.

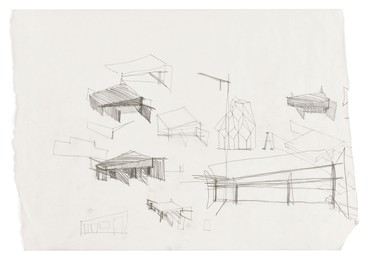

JLCA slightly different issue. This book is not a book of projects, it’s led by the drawings—mostly your own and sometimes drawings by others, including Gregory Walsh, who was a classmate of yours. Can you address this question of you drawing like Greg, Greg drawing like you, and other people contributing to this immense production, which is now stored at the Getty Research Institute, where much of your archive resides?

FGWell, one thing I should say about Greg is that he’s a classical pianist. So working with him on our projects for school, we would stay up all night working and listening to the Goldberg Variations [laughter]. He really got me into the highest level of classical-music thinking.

During that period we contrived to learn to draw the same so that we could work on each other’s projects for different deadlines. And now, with some of the drawings, I can’t tell whether they’re mine or his.

JLCYes, all the tricks historians use to identify drawings don’t work—the way cars, trees, people are drawn is totally similar. Maybe your handwriting is more specific.

FGWell, neither of us could draw people, so that was great [laughter].

JLC This book is the prototype for many more to come. When we started, five years ago, you, Staffan Ahrenberg, and I decided to make eight volumes. This took into account only the production to 2012, but almost ten years have passed since then and you continue to design and build intensely. So I don’t know where we’re ultimately going to land.

Basically, the story is what I would call a diachronic story: project after project with sketches carrying the narrative within each. We see the projects through the sketches. Sometimes there are almost none, sometimes there are hundreds, as with the beautiful Santa Monica Place Shopping Mall [1973–78], for example, which is now only a memory. The intent was to try to document the movement of the project: the different options, the turns in the relationship with the client, how the projects appeared. This is very clear, for instance, in the case of the Davis house, where one finds your sketches echoing what Davis was doing in his painting.

So it’s a sort of genetic story of each project based on sketches, plus other types of materials—ephemera, correspondence, notes—that give an account of what happened. I really love the way you wrote letters in those days, Frank, with fantastic one-liners, and you still continue today. I will only mention one that for me characterizes your work of that period. Mies van der Rohe famously said in an interview, “I don’t invent new architecture every Monday morning. I don’t want to be interesting, I just want to be good.” And in a letter to someone you said, “I don’t want to be good, I just want to be interesting” [laughter]. For me that’s the key to this part of your work and what follows.

FGA lot of people worked on these projects over the years. It’s not the sound of one hand clapping. We have 160 people in the office today.

JLCThat’s true. The book is also very explicit about the design team for each project. I’ve been talking with some of them from that time, hearing stories that allow me to understand better what happened.

FGIt’s a collaborative effort.

JLCAnd we see traces of that process in the drawings: “Let’s ask Frank what he thinks,” and we see your intervention with your answers. It’s clearly a chronicle. Anyway, hopefully we’ll see two more volumes in the coming year and a half. And I think we’re up for much more after that, since you’re—

FGI’m just beginning.

JLCYou’re going full speed ahead.

Text adapted from a conversation presented as part of Gagosian’s Building a Legacy initiative at Gagosian, Beverly Hills, in early 2020.

Works by Frank Gehry © Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66)