Paul Goldberger, whom the Huffington Post calls “the leading figure in architecture criticism,” won a Pulitzer Prize for his writing in the New York Times. The author of several books, including Why Architecture Matters and Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry, he has also served as architecture critic for the New Yorker and Vanity Fair, and he holds the Joseph Urban Chair in Design and Architecture at the New School, New York. Photo: Michael Lionstar

The fish that gives its shape to Frank Gehry’s fish lamps is not, as legend has it, the carp that he saw swimming in his grandmother’s bathtub that she would kill to make gefilte fish. Gehry’s grandmother did indeed buy a live carp every week when he was growing up in Toronto eight decades ago, and the image remains vivid in his mind. But the reasons the fish became totemic for him—the reasons he has echoed its shape in forms ranging from monumental sculpture to lamps—are more complex, and go deeper than his childhood, if not so far back in his life. Much of Gehry’s career as an architect has been based on an exploration of basic geometric forms and how they can be twisted, torqued, or divided into pieces to create new compositions that feel at once highly active and restful, even serene. Gehry has always been fascinated by curves and fascinated by movement. A fish, of course, represents a combination of the two: its form is a complex curve that resolves into a serene shape, and as it glides through the water, its undulations seem almost to accentuate its natural curves. Even when the fish is at rest, something about its shape seems to express movement. The scales, meanwhile, suggest that the fish is not quite so pure an object as it first appears to be, and that its appealing shape, at least on the surface, is made up of many little parts that come together—another tie to Gehry’s architecture, which often is made of disparate pieces that the architect has assembled into a coherent whole.

But the fish is more than a metaphorical expression of Gehry’s architecture. Its shape is primal. The fish is ancient, and its very connection to prehistoric times gives it another level of meaning for Gehry. In the mid-1970s, as architects began to move away from modernism and seek ways in which to incorporate historical form into contemporary architecture, Gehry was both intrigued and appalled. He shared the feeling that modern architecture had worked itself into something of a dead end, and he understood, at least intellectually, the appeal of looking with renewed sympathy at the historical architecture that a previous generation had all but dismissed as irrelevant. But in his heart Gehry remained a modernist. For all that he understood the limits of modernism at the time, it was never in his nature to look backward. He had never been comfortable with mimicking the forms of the past, and he was far more interested in finding other ways out of the dilemma of modernism’s aesthetic fatigue. The fish, for Gehry, was one of those ways—its form was emphatically not modern; perhaps even more to the point, it was not really a part of the architectural vocabulary at all.

No small part of Gehry’s pleasure in his appropriation of the fish shape stemmed from the fact that it was a way of upping the ante of historicism, so to speak. You want history? I’ll give you history, Gehry was saying. At a lecture at UCLA he went right to the point: “I can’t understand why we’re going back to the Greeks when we could go 300 million years back,” he said. Gehry was close to many of the postmodernists of the 1970s and ’80s, especially Philip Johnson, whose view of things seemed, at least briefly, to be on the ascent. But Gehry’s mocking rhetoric made it clear he had no interest in aligning himself with Johnson’s architectural approach, which he found glib and sentimental: “It was decorative, soft and pandering and all the things I didn’t care about, and I didn’t know how to deal with,” he later told the writer Barbara Isenberg. “The rest of the world seemed to be excited about it, but I was left behind. The train left the station with a new conductor, and I didn’t know how to get on it.”1

If the fish allowed Gehry to thumb his nose at historicism, it allowed him to do the same to critics who found his work too abstract, too unusual, or too distant from forms they recognized. No one could fail to recognize a fish.

So Gehry turned to the fish, at least in part as a way of solving the dilemma that postmodernism presented for him. He may have been making jokes when he said that the fish—which he called “the perfect form”—represented the return to history that the postmodernists advocated, but he was absolutely serious about seeing it as an inspiration for a new way of making modern architecture that would be both more sensual and more geometrically complex than the conventional modernist box. The double curves of the fish form fascinated him. So did its delicate skeleton, light and graceful in itself. The fish, he said, offered “a complete vocabulary that I can draw from.” He had plenty of other inspirations for his work, of course, but nothing else seemed so cogent a summary of his aesthetic. And it gave Gehry, an architect who generally shied away from conventional forms, the opportunity to use one of the most familiar shapes there is, and make it his own. If the fish allowed Gehry to thumb his nose at historicism, it allowed him to do the same to critics who found his work too abstract, too unusual, or too distant from forms they recognized. No one could fail to recognize a fish.

A fish is not a building, however, and its shape does not lend itself to being one. Gehry first experimented with using the fish form in the design of an entry colonnade for the Smith residence, an unbuilt project of 1981, in which “jumping fish” set a rhythm for the series of columns, at once extending traditional architectural form and subverting it. That same year Gehry tried to blow up a fish to the size of an entire building in his design for a hotel in Kalamazoo, Michigan, part of a larger downtown renewal project that was ultimately designed by another architect. Kalamazoo would have been only half a fish anyway: Gehry cut off the head, and stood the lower half of the body of the fish vertically, so that it could be taken, at least from a distance, as a sinuous tower. That same year, Gehry proposed a sculpture of an entire fish, balanced on its tail, as the centerpiece in the courtyard of a renovated complex of studio lofts on Crosby Street in Lower Manhattan, another project that was never realized.

At around the same time, Gehry was invited to participate in a project initiated by the Architectural League of New York that paired architects with contemporary artists and asked them to create something that neither would be able to do on his own. Gehry’s partner was the sculptor Richard Serra, with whom he concocted a gargantuan bridge to connect the Chrysler Building with the World Trade Center, both of which could be seen from the windows of Serra’s downtown Manhattan loft. Serra designed the supporting pylon at the Chrysler Building end, which would have been a huge tilted pylon set in the East River. Gehry designed the pylon at the other end, which he envisioned as a skyscraper-size fish, rising out of the Hudson River and holding the bridge’s cables in its teeth. Here, the fish made thematic sense in a way that it did not in Kalamazoo. It was leaping out of the water and catching the cable, a witty reversal of the normal relationship of a fish to a casting rod. It is hard not to think that Gehry was highly influenced here by his friends Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen—sculptors very different from Serra—since the bridge fish, like Oldenburg and Van Bruggen’s work, is a familiar object blown up beyond monumental scale to yield an object at once amusing and disquieting.

Gehry was excited less by the Oldenburgesque aspect of the bridge project than by what he had discovered when he produced a mock-up of a section of the skyscraper’s skin out of glass fish scales, which was that the scales created a complex, layered surface that was exactly what he would want, should he ever design a real skyscraper. He continued to look for ways in which to use the fish as a literal form and not merely as a metaphor for his architectural aspirations. In 1983, he proposed a glass fish, this time set horizontally, as a pavilion for an exhibition of architectural follies organized at the Leo Castelli Gallery by Barbara Jakobson—the first time he proposed creating a fish at the scale of a small building, with the interior a single room. (The Castelli fish was to be accompanied by a coiled snake, which Gehry envisioned as a private prison, its inmate supervised by the occupant of the pavilion. It is a rare instance of Gehry having created a semblance of a narrative for one of his projects, rather than letting their forms speak for themselves.)

Gehry had flirted from time to time with other creatures as well. He envisioned an abstracted eagle as the crown of the skyscraper he proposed as his entry into a mock architectural competition in 1980 that was intended as a contemporary homage to the one of the most famous architectural contests of all time, the 1920s competition to select a design for the Chicago Tribune tower. Another eagle topped the pediment of a porch Gehry designed for the house of the architectural historian Charles Jencks, which Jencks did not build.

But not all of his early attempts to insert biomorphic form into architecture were unrealized. Gehry’s design for the restaurant Rebecca’s, near the beach in Venice, California, was completed in 1985, its most striking feature a pair of large Gehry crocodiles hanging from the ceiling. There was also a mammoth chandelier in the form of a glowing octopus, made of thousands of individual hanging crystals, and two large standing lamps that, like the Kalamazoo project, took the form of the body of a fish, without its head. (Gehry commissioned several of his artist friends in Los Angeles to create other elements of the restaurant. Ed Moses made a window with images of tarantulas, Peter Alexander made a mural in black velvet, and Tony Berlant designed the front doors. The restaurant was demolished in 1998.)

After Rebecca’s, several other fish projects went forward. Gehry designed a 14-foot-high glass sculpture of a fish for the retrospective exhibition of his work at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in 1986, and a 37-foot-long fish with scales of plywood was built in Italy in 1985 as a traveling sculpture installation commissioned by Italian fashion house GFT. If the Italian fish came closer to being a real piece of architecture—it was possible to enter it and remain within it—the shape of the Minneapolis fish, thrust upward with its tail curved beneath it, prefigured the shape Gehry would use for his first truly monumental fish, the Fishdance Restaurant on an industrial waterfront site in Kobe, Japan, finished in 1987. The Fishdance is a complex of three structures: a copper-clad spiral that is an abstracted version of a coiled snake; a large, shedlike structure with a glass tower; and, most important, a 70-foot-high fish sculpture sheathed in a mesh of chain-link metal. The fish is the tallest element in the complex, but it looks as if it were about to leap higher still—Gehry’s belief that the form of the fish inherently connotes movement seems even more apparent at this large scale. The enormous fish is at once a realistic sculpture and a pure abstraction—you feel it both ways, as Gehry does. That is the real triumph of the Fishdance: it makes you understand the inherent nature of a fish, even as it makes you view it as a pure, swooping shape.

It was in 1983, after Gehry had been playing casually with the form of the fish for a couple of years, that he was approached by the Formica Corporation, which had recently introduced a new plastic laminate called ColorCore. Unlike traditional plastic laminates, which have color only on the surface, ColorCore features color that extends all the way through the material, giving it edges that are the same color as the surface. To draw attention to the design potential of its new product, Formica was commissioning noted designers to create new objects with it, and invited Gehry to be part of the group. He agreed, as much because he was intrigued by the fact that the material was translucent—at least in lighter colors—as with its color consistency. Mixing the light, translucent colors and darker ones, which were more opaque, in the form of a lamp seemed to Gehry an appealing way to explore this aspect of the material. At first, he did not think of the project as having any connection to his interest in the fish form, and his earliest attempts at lamps had nothing to do with fish. One was essentially a box, which Gehry, frustrated, felt was little more than a version of Isamu Noguchi’s famous paper lamps rendered in Formica. It was only when one of the prototype lamps was accidentally broken that Gehry noticed that it had shattered into shards, with rough edges that might, to others, have been thought to resemble arrowheads. But to Gehry they were the scales of a fish, and suddenly he realized that his ColorCore project could be a lamp in the form of a fish or, for that matter, a snake.

And thus the first set of fish lamps was created in 1983, almost by accident, not as a deliberate design project so much as part of a corporate effort to promote a new material. To fabricate the lamps, Gehry turned to Tomas Osinski, an artist and craftsman who had helped him with other projects over the years; Osinski, working from Gehry’s sketches, created multiple variations of both fish lamps and snake lamps out of ColorCore Formica, all of which glowed from within, highlighting the translucency of the material. Gehry kept the first fish lamp and turned the second one over to Formica, and then one of the lamps was seen by an art dealer, who offered Gehry $100 for it. Word of the lamps began to spread through the art world, and the collector Agnes Gund asked Gehry to create one as an engagement gift for her brother, the architect Graham Gund, which Gehry sold to her for $1,000. Requests from Philip Johnson, Jasper Johns, and Victoria Newhouse followed, confirming that the lamps had quickly become a fashionable item to collect. More lamps followed, and in 1984, Gagosian Gallery put twenty of them on exhibit at their space at 510 North Robertson Boulevard, Los Angeles.

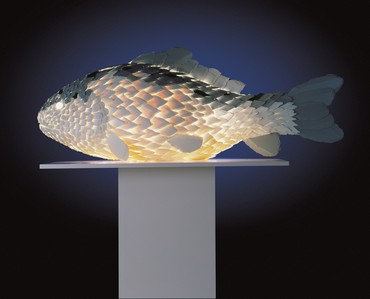

For all that Gehry wanted to celebrate the fish as a creature in motion, the lamps in the first exhibition were somewhat static: the fish sat on pedestals, some simple boxes and some of Gehry’s own design, and they seemed to stare straight ahead, frozen in space. They were illuminated sculptures more than true lamps, since they provided no ambient light to speak of, but by calling them lamps and not sculptures Gehry made them seem a bit closer to architecture, rendering them more distinctive than sculptures, and hence more valuable. Many artists had made sculptures of fish, but there had never been a lamp in the form of a fish, and these early lamps looked like nothing anyone had ever seen before. Gehry had not yet narrowed his focus to the carp, and the early fish tended to be shorter, stockier, even a bit puffier than the carp. They glowed elegantly, but a bit ominously at the same time.

By the late 1980s, Gehry was winning major commissions as an architect, and while the lamps continued to increase in value, they seemed more like a footnote to his career than a central preoccupation. Their ongoing appeal lay, at least in part, in the connection they offered to his early years, when his work was rough-hewn, celebrated everyday materials, and affected a certain air of casualness. The Formica fish lamps seemed to belong more to the Gehry of plywood and chain-link fencing than to the Gehry of titanium and stainless steel—indeed, they seemed particularly at home in early Gehry projects, such as his own house in Santa Monica, where the first fish lamp has remained for thirty years.

In 2012, Gehry returned to the making of fish lamps, and their design reflected the evolution of his architectural work in the intervening decades. If the early fish lamps are like Gehry’s house in Santa Monica—rough, stolid, direct, and strong—the later ones are the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, or the Walt Disney Concert Hall, full of energy, lyrical shape, and a graceful grandeur. The sense of movement that Gehry sought to express is now absolutely clear. The new fish lamps were not created with the digital software that enabled Gehry to engineer and build his newer architectural forms, but they might as well have been, since the second generation of lamps seems to leap, to dive, to jump; the fish have become lithe and acrobatic, and they seem almost to reflect the curves of Gehry’s buildings.

The new fish lamps are for the most part considerably larger than those of the first generation, and more admittedly sculptural. When they were shown in 2013 at Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills, in an installation designed by Gehry (which was followed by similar exhibitions in Paris, London, and, in 2014, Hong Kong), together they almost formed a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total experience of light, form, and space, not a series of disconnected, one-off pieces. There were fish on walls, fish standing on their heads like acrobats, fish hanging from the ceiling. The fish played off each other, sometimes in choreographed arrangements that recalled water ballet. Where there was a fish on a pedestal, which is how they were all displayed in the show twenty-nine years earlier, it was now likely to be larger than the pedestal, ready to fly off it. Everything in Beverly Hills, and later in Paris, London, and Hong Kong, was part of a larger composition, orchestrated by Gehry so that the new fish commanded the expansive space with a degree of self-assurance, not to say showmanship, in a way the originals never could.

Yet the fish remain, still, all of a piece: more connects the first- and second-generation Gehry fish than divides them. The recent fish have not lost the sense of quirky mystery that marked the originals, the sense that there is something at once beautiful and outrageous about them. Like their predecessors, the new fish glow, their ColorCore Formica scales still blending translucency with opacity, and they possess a sumptuousness that surely compensates for the loss of the raw, tentative energy of the first generation of fish lamps. Like Gehry’s architecture, the fish lamps have matured, and with them he has built on what came before, not rejecting it but bringing out of it something grander, more powerful, and even, at its best, majestic.

1Barbara Isenberg, Conversations with Frank Gehry (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), p. 127.

Artwork © Frank Gehry; text originally published in Frank Gehry: Fish Lamps (New York: Gagosian, 2014)