Miciah Hussey is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York. He holds a BA in art history from Vassar College and a PhD in English Literature and Critical Studies from the Graduate Center at the City University of New York. His writing has appeared in Artforum, Art in America, The Henry James Review, and Victorians.

It is in playing and only in playing that the individual child or adult is able to be creative and to use the whole personality, and it is only in being creative that the individual discovers the self.

—D. W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality, 1971

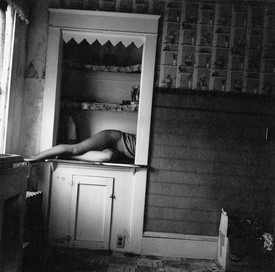

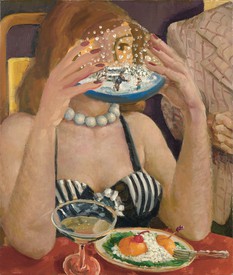

Bodies are unruly things, and we are preposterously entangled with them. But Finnish photographer Iiu Susiraja unknots this relationship by positing embodiment as just another readymade in an object world held under the sway of her fecund interiority. In a series of humorous, formally complex self-portraits, she interacts with a battalion of banal household items, employed as part prop, part costume, part dramatis personae. In one, she poses in a simple blue bathing suit with a single crooked mannequin arm swimming between her fleshy thighs, in another she holds a fish whose eyes have been popped out and placed on her shirt like nipples, and, in one of her more baroque tableaux of dollar-store fever dreams, she is dressed like the Easter bunny, rides an elliptical machine, and holds a grim reaper’s scythe blunted with a faux cottontail. Below the surface of her eccentric compositions is an investigation of a number of issues clustered around the body—issues of size, of gender, of performance—that questions how we see ourselves as functioning with and among a network of things. Articulating a series of playful if provisional object relations, her photos compel an accounting for excess that is not merely physical but also psychic.

The static portrayals held within the confines of Susiraja’s photographic frame riff off British psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott’s notion of the “transitional object”—those soft or hard toys that usher the infant into the realization of things that are “not me.” While neither the teddies nor the blankets nurtured by the child, the readymades of late capitalism engage Susiraja in a cathexis that enacts, in a visual idiom, what Winnicott calls the transitional phenomena of experiencing. He claims that this space between interior and exterior life “shall exist as a resting-place for the individual engaged in the perpetual human task of keeping inner and outer reality separate yet interrelated.”1 Susiraja animates this resting place by representing herself at play, treating her own body with the same plastic objectivity with which she approaches the plungers, folded shirts, balloons, and other items in her photos. Like Melanie Klein’s “depressive position,” which offers part-objects to nourish a self in process, Winnicott’s resting place, especially as illustrated in Susiraja’s work, is a potent site of creation—not only resulting in striking compositions but also illustrating a surplus stratum of self. Both the fun and the pathos of her photographs come from its striking inversion of Winnicott’s notion of “fantasying”: the empty daydreams of a false omnipotence in which “what happens happens immediately, except that it does not happen at all.”2 Susiraja instead makes images of real life and relationships to the world. The more oddball the object she employs, the wackier the mise-en-scène, the more she explores herself beyond the boundaries of a body, extending her interiority to repurpose an object world into a site where dream and life can be the same thing.

But what glimpses into psychic interiors do Susiraja’s photographs offer in this time of sequestered isolation? More astute than the TikTok dance-offs that occupied many in the recent quarantine, these works confer a plentitude of formal rigor and intellectual pleasure on the kind of domestic play that Susiraja elevates into incisive cultural critique. Via outré interactions with the inanimate, her work dismantles the old Enlightenment standby of mind/body dualism: in blurring the dichotomy between obdurate physicality and dynamic being, she is able to capture a self constantly querying itself. Through her props, no matter how banal, how perverse, or how silly, Susiraja actively rethinks the underpinnings of embodiment—its physicality in space, its culturally induced performances of gender, and its biologically compelled sexuality. Susiraja’s blank stare at the viewer—registering a moment of affectlessness just prior to the surprise of being caught in flagrante delicto—defers narrative and the closing in of the violence of overdetermining signification.

Susiraja is fond of her own translation of Swedish poet Bruno K. Öijer: “As long as they have the wrong picture of you, they can’t harm your life,” which is an apt motto for both visual and psychic rhythms in her work. In presenting “the wrong picture,” she obviates cultural conclusions many may draw from a kind of body that is alternately demonized or fetishized. But further, she draws a stark line in the sand between art and life—a line all the more necessary because of how her body may invite insidious autobiographical readings. As any person of size may tell you, sneering eyes of fellow commuters and unsolicited health advice from strangers are just two of the many ways in which the overweight body signifies a sort of crowdsourced narrative of not-so-tacit judgment and blame. However, the “wrong picture” becomes the armor for a “life” unharmed by a barrage of violent “body-negative” sentiments encased in the biased cultural eye. Furthermore, such barbed whimsicality more importantly points to a creative interior life that is celebrated as the agent of visual provocation. Susiraja disregards the autobiography determined by others in favor of the prelingual chora of her own off-kilter accoutrements. Stripping the contemporary object world of its use value, she resuscitates it for its indeterminate formalism, humorous non sequiturs, and potential to articulate a visual dream logic of self-creation out of domestic detritus.

1D. W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality, 1971 (reprint ed. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2005), p. 3.

2Ibid., p. 37.

Artwork © Iiu Susiraja

“New Interiorities” also includes: “Becoming Together” by Alison M. Gingeras and Jamieson Webster; “Living Death” by Jacqueline Rose; “Vera, Lateral Puncture” by Deana Lawson; “You Should Leave” by Alissa Bennett; and “Pathologically Optimistic: A Conversation with Paul B. Preciado”