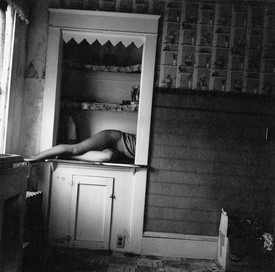

Alissa Bennett is the author of Dead is Better, a twice-yearly zine devoted to tales of woe, depravity, drug crimes, and love. The cohost, with Lena Dunham, of the podcast The C-Word, she is working on her first novel. Photo: Leigh Ledare

Among the most oft-repeated anecdotes of author Patricia Highsmith’s life is one that reputedly took place before she was even born. Pregnant and facing the calamitous uncertainty of a failed marriage, Highsmith’s mother, Mary, is said to have resorted to drinking turpentine in an attempt to abort the fetus inside her. “It’s so funny,” Mary would later tell Highsmith, who as an adult found pleasure as a Sunday painter, “that you love the smell of turpentine.” That one might eventually develop a fondness for the agent of their would-be death sits neatly within the broader scope of Highsmith’s work, which recurrently deconstructs the intimacies between criminally minded charlatans and their accidentally complicitous faux-amis. She is widely hailed as the high priestess of suspense fiction, but her power as a writer is often most acutely revealed in the interstitial moments of calm that interrupt her depictions of violent rupture—the anxious hours that pass before understanding that a force-fed dose of poison has not killed you after all.

A critical component in Highsmith’s development and deployment of literary tension is the construction of the prismatic identity, and though frauds, fakes, and counterfeits surface with great regularity across her pages, at each antihero’s core is a profound desire to locate the supplemental other. In Strangers on a Train (1950), Guy Haines objects immediately to Anthony Bruno’s train dining-car proposal for a quid quo pro murder, but the liminal space that stretches between stations offers sufficient suspension of reality to stoke Bruno’s fantasy that he has encountered a partner in crime. Highsmith often used travel as a literary device, and the exchanges and self-contemplation that unfold between departure and arrival typically serve as stages on which her characters can rehearse the manifold consequences of possibility. It is only in these caesuras that Highsmith’s antiheroes can manage to consolidate their identities, only in the in-between that they find ways to briefly stave off the burden of their profound alienation.

Much analysis of Highsmith’s work has been dedicated to her own notorious misanthropy: she has been characterized as an eccentric, an alcoholic, a misogynistic lesbian, and a profligate fibber with ugly prejudices and an acid tongue. Despite her legendary distaste for humanity at large—she famously once remarked “I don’t like anyone”—she perhaps came closest to confessing her longing for a steady collaborator in The Price of Salt, a work that is widely referred to as her “lesbian novel.” Published in 1952 under the pseudonym Claire Morgan and later rereleased under Highsmith’s own name and with the title Carol, the book details the relationship between a nineteen-year-old shop clerk and a dissatisfied housewife whose chance encounter in a department store sets into motion a socially verboten love affair. Fleeing an impending court case that threatens to expose Carol’s lesbianism, the women leave New York and drive west until they are sufficiently liberated by distance to act on their mutually repressed desire. To move, in Highsmith’s literary universe, is to defy the bondage of identity, to cast off the claustrophobic psychic genealogies that dictate to each of us how and what we are supposed to be.

In both fiction and life, Highsmith viewed peripateticism and relocation as the only true opportunities for reinvention of the self (or selves).

It is telling that Highsmith returned most often to the character of Tom Ripley, the strangely sympathetic psychopath whose audience roots for his continued freedom despite the homicidal immorality of his actions. The writer’s devotion to this particular protagonist, and the literary acrobatics she repeatedly employed to ensure his freedom, are perhaps indicative of a fantasy that all transgressions dissolve if we are only able to get far enough away from them. Much like Ripley, the writer expatriated to Europe in the early 1960s, a gesture that established geographic distance between herself and a personal history she thought better off discarded. In both fiction and life, Highsmith viewed peripateticism and relocation as the only true opportunities for reinvention of the self (or selves). To remain rooted too long, to be too fixed to one place, opens one up to the violence of discovery. “No writer would ever betray his secret life,” Highsmith once wrote to a friend. “It would be like standing naked in public.”

If Highsmith did not betray her secret life, she certainly detailed her tools of evasion. The impressive volume of her work—she completed twenty-two novels, eight thousand pages of journal entries, and eight collections of short stories—suggests a woman compelled to write herself out of the intractable oppression of reality. Though her characters’ sociopathic restlessness often brings them to the verge of exposure, they constantly find another forgery, another boat or bus or car that loops them back into a perpetual process of becoming.

And what would Highsmith make of 2020’s global lockdown and grounded planes? Of our hermetically sealed borders and dry-docked steamer ships? I do not imagine her weeping over flabby loaves of dough or wistfully text-messaging a hairdresser in commemoration of a missed appointment. I envision no artificially cheerful toasts conducted via computer screen (Highsmith preferred the company of her pet snails to parties anyway), no piles of doomed arts-and-crafts projects going to seed in wicker baskets, no half-finished jigsaw puzzles. Like all professional fugitives, Highsmith would have known that the interstice is the perfect place to plot an unlikely getaway and that the best crimes are hatched while we are locked up tight in our cabins, late at night and drifting across the sea.

It seems particularly fitting that in her own final moment of transit, Highsmith tried her hand at one last bluff. Lying in a hospital in Locarno, Switzerland, she reportedly drove her devoted accountant from her bedside by repeatedly uttering the phrase “You should leave” with a grave insistence. Once safely unattended in the room, Highsmith closed her eyes and promptly died. We are, she maybe wanted to suggest, always able to figure out who we want to be next when we get to be alone.

“New Interiorities” also includes: “Becoming Together” by Alison M. Gingeras and Jamieson Webster; “Living Death” by Jacqueline Rose; “Vera, Lateral Puncture” by Deana Lawson; “Pathologically Optimistic: A Conversation with Paul B. Preciado”; and “Resting Place” by Miciah Hussey