Jacqueline Rose is internationally known for her writing on feminism, psychoanalysis, literature, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. On Violence and On Violence against Women will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the spring of 2021. A regular writer for The London Review of Books, she is professor of humanities at Birkbeck University of London.

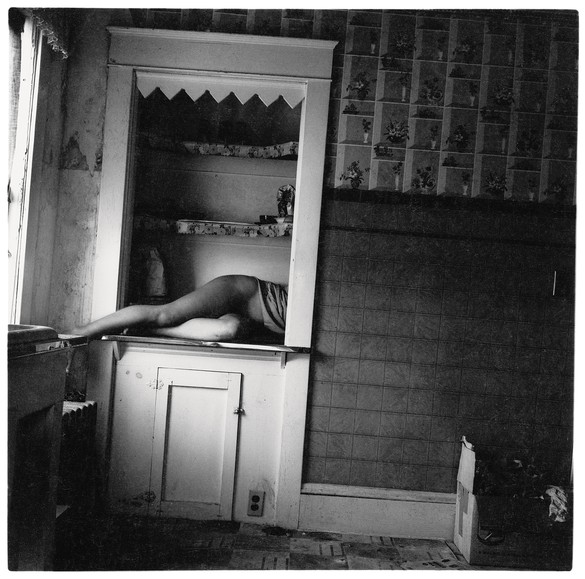

What exactly is being asked of people when they are told to “stay at home” or “self-isolate” in response to the covid threat? In a recent BBC Panorama report on women who have managed to escape their abusers during lockdown, one woman was asked, “What did the ‘stay at home’ message mean to you?” “Death,” she replied almost inaudibly, and then repeated the word as if not expecting to be heard.1 Her partner damaged her internally, she said, and burned her with cigarettes “so no one would want me.” He also never left her alone in a room; she was isolated, yet never by herself: cut off from most human contact and at the same time deprived of privacy, robbed of the capacity to find a way through her own thoughts. This is isolation without interiority, solitude leeched of its inner dimension, loneliness without redress. It leaves you with no one to turn to, including yourself. The “self” in “self-isolate” is therefore a decoy. It forgets all those situations—incarceration, torture—where isolation is something that one person (with the power) inflicts on another. Above all, it leaves no room to ask what happens, during a time of collective trauma, to the mind’s innermost relationship to itself.

No less misleading is the mantra, at the center of lockdown policies worldwide, that staying at home will save lives (or, in one sinister government ad widely circulated on Facebook, “If you go out, you can spread it. People will die”). Without consideration of whether staying home is possible, or what might follow when it is, this turns the body into a lethal weapon outside the sacred precincts of the home. The formula is an avatar for privilege and injustice. What are the advantages of staying indoors for a family crowded into an airless slum? Or for the low-paid workers living in cramped conditions as a result of the rising, pandemic-fueled demand for cheap factory-produced food? Against decades of feminist argument, the phrase also makes the fatal error of suggesting that the moment you reach your front door, you are safe. In the United States, women are being prevented by their abusers from washing their hands so that, even in isolation (especially in isolation), their fear of infection will increase.2 In England, one couple sat listening to Boris Johnson on the radio when he announced the lockdown. “He looked over at me,” the woman later described her husband, “he had his arms folded and his chest out, ’cause he knew that would intimidate me, and he said, ‘Let the games begin.’” He then raped her in an invisible, silent world: curtains closed, front door locked, TV and music both turned up so loud that no one could hear her screaming “for someone, for anybody.”3 This is isolation at degree zero, trampling over the relics of what, not so long ago—though it feels like the distant past—was meant, for some at least, to have been a relatively safe world, a time when women in many countries, though not all women, felt more or less free to walk out the door. Neither health benefit nor saving grace, the official guidance has proved itself to be the hidden accomplice of cruelty, a spur to violent gender-based crime.

Slowly these stories are coming to light. The problem is global—the “shadow pandemic,” in the words of a United Nations report4 —yet for some reason it does not seem to have crossed the minds of those in government that lockdown would be a nightmare for women trapped in abusive relationships (though I am not sure why this should come as any surprise). Visits to the website of Refuge, the United Kingdom’s largest domestic-abuse charity, have increased during the pandemic by 950 percent; at one point there was a 700 percent increase in calls in a single day.5 True, there was a clause in the UK Coronavirus Act of April 2020—intended, we have since been told, for women abused in their homes—allowing that not everyone would be able to self-isolate. But the only person who seems to have made use of that clause is Boris Johnson’s unelected chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, to excuse his breaking of lockdown rules when—infected with covid-19—he traveled with his family to stay with his parents in Durham. By doing so, he smashed any remaining confidence in government policies, putting thousands at risk. Britain shares with the United States one of the highest infection and death rates in the world.

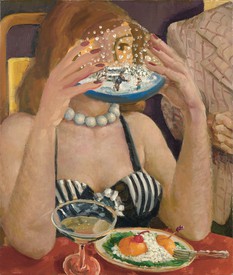

Women are being punished—paying with their lives—for a death that has become too visible, for the bodies that are failing and falling all around, as defenses start to crumble and the phobic core of being human rises to the surface and explodes.

It took nineteen days after the lockdown began for funds to be released to women’s refuges, which were desperately straitened after years of government austerity policies. During that time, eleven women were murdered by their partners—more than double the average number for such killings during an equivalent period before the pandemic.6 “If you think it was bad before,” the husband said, “you are in for a rough ride.” (“Let the games begin.”) Lockdown had emboldened him, giving him a new lease on life and on death. Another woman, pregnant, was force-fed—it started as a game, almost like a fetish, she said. Her partner boasted that he didn’t have to “cover up” any more while repeatedly assuring her that she was safe at home (he would not let her leave the house to attend a hospital pregnancy scan).7 Annie (not her real name) had endured two years of domestic abuse when the restrictions were imposed: “It was at this moment she finally started to believe her partner would kill her.”8 Abuse in a time of pandemic—angry men walking into shuttered rooms with “guns” blazing and a soft voice. Or, as one poster plastered across London puts it, “Abusers always work from home.”

Although more men than women worldwide are dying of covid-19, we are faced with a new “femicide,” the term originally coined by Diana Russell in 1976, and that the pandemic has brought out of the dark. With reference to covid, psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva uses the term “feminicide,” since it is women’s presumed “femininity” that is at stake.9 There is, Kristeva suggests, a central “phobic core” to all humankind, an inner fear of mortality and of life’s fragility that we normally push to the back of our minds, stuff into the back drawer of the arrangements through which we organize and delude ourselves. Against such unconscious knowing, it is above all the task of women to make their partners, children, and dependents feel secure, to sweep the dirt and debris away. This is the heartbeat of so-called “femininity,” to which, of course, in a time of pandemic, no woman can possibly be equal (nor at any other time, it should be said). Feminicide, then, is the enraged response to women who betray this prescribed essence of the feminine. They are being punished—paying with their lives—for a death that has become too visible, for the bodies that are failing and falling all around, as defenses start to crumble and the phobic core of being human rises to the surface and explodes. To which we might add that women are being assaulted by men who feel, as they too are confined to the home, that they are being turned into women.10

We are living an epoch of permanent grief, a time of psychic reckoning that feels too much to endure. Cherished illusions are suddenly stripped bare—it is as if the end of illusion, an end that Freud fervently desired in relation to religious belief, had suddenly come upon us without warning out of the skies, summoning the deepest fears of the soul. It was Freud’s argument that religion served above all to keep fear of mortality at bay; his mistake was to think that, for that very reason, any such belief was an illusion that, over time, the powers of the reasoning mind were bound to dissipate. (Surprisingly for Freud, that argument runs contrary to a basic tenet of psychoanalysis: nothing perishes in the unconscious.) Today, faced with this new psychic dispensation, many rulers across the globe are battening down the hatches, laying down the law as to what they can or will tolerate, internally and in the world they claim to own. It is not working. The world refuses to bend to psychotic conviction, to the omnipotent belief in the powers of the human mind (Jair Bolsonaro, Donald Trump). In a time of pandemic it rapidly becomes clear that you cannot force the world to your will—the wager of dictators throughout history. Nor can you pretend that the body is within your control, now or ever. A virus mutates, shunts invisibly through the atmosphere, carries itself by means of droplets we cannot even feel on our face (which is why the reassurance provided by wearing masks is so flimsy). At any given moment, and regardless of the precautions we take, covid-19 could be anywhere.

The problem, then, is not only that women are being sent back to the home, where they are once again taking on the lion’s share of domestic work, home schooling, and everything else; it is also that, according to a well-worn tradition and grievance, this reality is unseen.

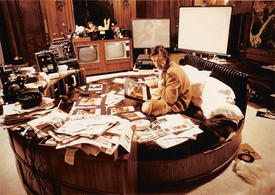

And yet, in the teeth of this unbiddable reality, the mind’s capacity for delusion, for transcending and at the same time wallowing in the mire, if anything intensifies—especially for those who feel power slipping from their grasp. As the extent of viral spread registered in Brazil, a spread largely the outcome of Bolsonaro’s denials, he boasted that the people of his country could swim in excrement and emerge unscathed (why they would want to do so is unclear).11 The analogy is as revealing as it is nonsensical: unlike shit, a virus does not respond to muscular exertion, which in fact it often fatally undermines; it cannot be expelled. Bolsonaro has further stated that if we must fight the virus—a major concession—we must do so “like fucking men.”12 The only reason, he insists, that he has a daughter, who was born after his four sons, is because at the moment of her conception, he had a moment of weakness and failed properly to concentrate.13

The options for women are stark: back to the 1950s, “the Great Leap Backwards,” as it is being termed (backlash with a vengeance); or straight into the eye of the storm.14 Today, all women’s hard-won workplace victories in terms of hours, promotions, and equal pay, and in relation to child care and domestic labor at home, are in danger of being lost (not that any of this had been fully achieved prepandemic). “With the schools closed,” Eliot Weinberger writes in his essay “The American Virus,” “45 percent of men say they are spending more time home-schooling than their wives. Three percent of women say their husbands are spending more time home-schooling than they themselves are.”15 The problem, then, is not only that women are being sent back to the home, where they are once again taking on the lion’s share of domestic work, home schooling, and everything else; it is also that, according to a well-worn tradition and grievance, this reality is unseen. (I remember my shock as a young woman when a friend made the obvious point that the success of domestic work is measured by its ability to wipe out every last trace of itself.) Angela Merkel has warned of a creeping “retraditionalization” of roles.16 The domestic workload of women in France has tripled since March.17 In Spain, more than 170,000 people have signed a petition protesting against this “regression.”18 In the United Kingdom, the “early years” sector is on the brink of collapse: one in four preschool nurseries risks closure within a year.19 According to the British campaign group Pregnant Then Screwed, more than half of pregnant women and mothers expect the pandemic to have permanently damaged their careers.20

We might then ask how it is that according to a survey of 194 countries conducted by the Centre for Economic Policy Research and the World Economic Forum, countries dealing much better with covid-19 are led by women: Germany’s Merkel, New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern, Denmark’s Mette Frederiksen, Taiwan’s Tsai Ing-wen, Finland’s Sanna Marin, Barbados’s Mia Mottley—a fact that has received little attention.21 Fewer cases. Fewer deaths. Women leaders are apparently both more risk averse with regard to fatalities and more willing to take risks with the economy, which, for most male leaders, is the privileged, inviolable domain, the driver of the “normal” to which they are so keen to return (as if, given the state of the world, “normal” is something that anyone should want or believe themselves to be). Taking the true measure of death, it would seem, is paradoxically the only way to prevent it from carrying off thousands, if not millions, of people before their time. In Barbados, tests were carried out several weeks before the first case had even been identified.

To live, you have to allow death into the frame. You have to open the inner world to what is most painful to contemplate.

“The evolution of civilisation,” Freud wrote in Civilisation and its Discontents, “is the struggle for life of the human species.”22 But to struggle for life, you first have to recognize death as its inevitable outcome, which is why Freud could also assert without contradiction that the human organism wants above all to die after its own fashion.23 To live, you have to allow death into the frame. You have to open the inner world to what is most painful to contemplate. In a letter of 1929 to Albert Einstein, Freud warned that psychoanalysis will always provoke resistance, because getting people to turn inward, away from the outer world where “dangers threaten and satisfactions beckon,” is so contrary to nature that it feels as if someone were “twisting their necks.”24 Today, psychoanalysts—faced with the strained intimacy of the virtual session—are confronting an outpouring of anguish, unbidden memories, traumas never before spoken of, alongside a struggle to hold on to one of the few spheres in our culture where the task is to accept the fullest psychic responsibility for oneself (psychoanalysis as the opposite of housework in how it deals with the mess that we make). Needless to say, this fractured shared space could not be further from a threatening home in which your only options are to smother your thoughts, get the hell out, or hang on in there for dear life. It might be too that this, or something close to it, is a space in which aesthetic work becomes possible, offering us another form of creative accountability, exposing the fault lines of the moment, providing a countervision in an unjust and collapsing world.

In these remarks I have overstated the division of the sexes—focusing on the worst-case scenarios as, under the pressure of the pandemic, the most forbidding versions of sexual difference are granted an ugly new freedom to roam. At the same time, we should remember that it is the—life-saving—wager of psychoanalysis, for both men and women, that everyone in the unconscious and in their deeds is capable, even under duress, of being more flexible in their identifications, less obdurate in their hatreds, always potentially other to themselves. Nor, crucially, as Black men are gunned down by police and vigilantes, is gender division the only fake division in our culture that, underscored by the pandemic, is tearing people apart on and off the streets. Nonetheless, the harsh fate of so many women in lockdown, alongside the gift of women leaders who are beating their unique path through disaster, might have a lesson to teach us. If the hardest task in the struggle for life is to give death its place at the core of being human, then perhaps one reason so many women are being punished during this pandemic is because they are more willing to do so.

1“Escaping My Abuser,” Panorama, BBC, August 17, 2020.

2See Andrew M. Campbell, “An Increasing Risk of Family Violence during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Strengthening Community Collaborations to Save Lives,” Forensic Science International Reports, April 12, 2020. Available online at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7152912/ (accessed September 7, 2020).

3“Escaping My Abuser.”

4United Nations, Policy Brief: The Impact of Covid-19 on Women, April 9, 2020, 19. Available online at www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/report/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en-1.pdf (accessed September 7, 2020). Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director, UN Women, “Violence against Women and Girls: The Shadow Pandemic,” April 6, 2020. Available online at www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/4/statement-ed-phumzile-violence-against-women-during-pandemic (accessed September 7, 2020).

5Mark Townsend, “Revealed: surge in domestic violence during covid-19 crisis,” Guardian, April 12, 2020. Available online at https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/12/domestic-violence-surges-seven-hundred-per-cent-uk-coronavirus (accessed September 7, 2020). Gaby Hinsliff, “The coronavirus backlash: how the pandemic is destroying women’s rights,” Guardian, June 23, 2020. Available online at www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/jun/23/the-coronavirus-backlash-how-the-pandemic-is-destroying-womens-rights (accessed September 7, 2020).

6“Escaping My Abuser.”

7Ibid.

8Jamie Grierson, “‘I live in fear of the unknown’: Life in a Refuge under Lockdown,” Guardian, May 21, 2020. Available online at www.theguardian.com/society/2020/may/21/i-live-in-fear-of-the-unknown-life-in-a-refuge-under-lockdown (accessed September 8, 2020).

9Julia Kristeva, “La situation virale et ses résonances psychanalytiques,” webinar, June 14, 2020. Available online at www.ipa.world/IPA/en/IPA1/Webinars/La_situation_virale.aspx (accessed September 8, 2020). On femicide see Diana E. H. Russell and Nicole Van de Ven, Crimes against Women: Proceedings of the International Tribunal (Millbrae, CA: Les Femmes, 1976).

10See Andrea Long Chu, Females (London and New York: Verso, 2019).

11See Tom Phillips, “Jair Bolsonaro claims ‘Brazilians never catch anything’ as Covid-19 cases rise,” Guardian, March 27, 2020. Available online at www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/mar/27/jair-bolsonaro-claims-brazilians-never-catch-anything-as-covid-19-cases-rise (accessed September 8, 2020).

12Jair Bolsonaro, quoted in Phillips, “Brazilian left demands Bolsonaro resign over Coronavirus response,” Guardian, March 30, 2020. Available online at www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/30/tp-captain-corona (accessed September 20, 2020).

13See Kate Lyons, “Far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro wins presidential vote—as it happened,” Guardian, October 8, 2018. Available online at www.theguardian.com/world/live/2018/oct/28/brazil-election-2018-second-round-of-voting-closes-as-bolsonaro-eyes-the-presidency-live?page=with:block-5bd63991e4b05fc14b59ed46 (accessed September 8, 2020).

14Hinsliff, “The coronavirus backlash.”

15Eliot Weinberger, “The American Virus,” London Review of Books 42, no. 11 (June 4, 2020).

16Angela Merkel, quoted in Kate Connolly, Ashifa Kassam, Kim Willsher, and Rory Carroll, “‘We are losers in this crisis’: research finds lockdowns reinforcing gender inequality,” Guardian, May 29, 2020. Available online at www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/may/29/we-are-losers-in-this-crisis-research-finds-lockdowns-reinforcing-gender-inequality (accessed September 8, 2020).

17Ibid.

18Ibid.

19Hinsliff, “The coronavirus backlash.”

20Ibid.

21See Jon Henley, “Female-led countries handled Covid-19 better, research finds,” Guardian, August 19, 2020, available online at www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/18/female-led-countries-handled-coronavirus-better-study-jacinda-ardern-angela-merkel; and Judy Stober, Letters, Guardian, August 25, 2020, available online at www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/24/women-excel-in-handling-covid-19 (both accessed September 8, 2020).

22Sigmund Freud, Civilisation and its Discontents, 1930 (1929), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. James Strachey in collaboration with Anna Freud, vol. 21 (London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1961), p. 122.

23Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, 1920, in The Standard Edition, vol. 18 (1955), p. 39.

24Freud, letter to Albert Einstein, March 26, 1929, quoted in Ilse Grubrich-Simitis, Back to Freud’s Texts: Making Silent Documents Speak, trans. Philip Slotkin (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996), p. 11.

“New Interiorities” also includes: “Becoming Together” by Alison M. Gingeras and Jamieson Webster; “Vera, Lateral Puncture” by Deana Lawson; “You Should Leave” by Alissa Bennett; “Pathologically Optimistic: A Conversation with Paul B. Preciado”; and “Resting Place” by Miciah Hussey