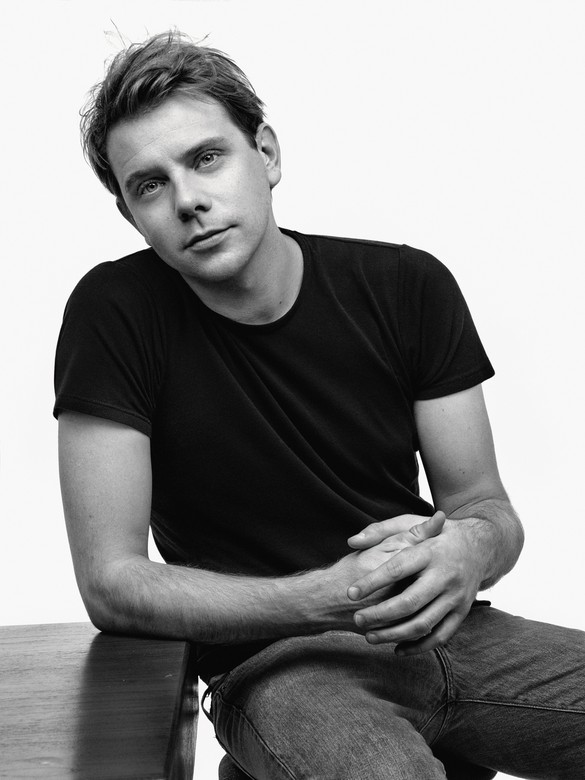

Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

Derek BlasbergYou and I are supposed to talk about the intersection of the fashion world with art and contemporary design, but with you, there are so many places to start. You head the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize; you have a collaboration with the estate of Tom of Finland that’s about to come out; you’ve worked with the foundation of David Wojnarowicz—

Jonathan AndersonWe have another one coming out with Wojnarowicz soon too.

DBAnd another with Paul Thek. So where do you want to start?

JAAt the beginning? I’m the creative director of two brands, Loewe and my own brand, JW Anderson. I’ve always asked, “How do you show your influences and at the same time create a platform to convey a message?” At Loewe I wanted to build a platform that was trying to break down the barriers between craft and art and fashion. That’s why we started the Craft Prize, and to use the influence of the brand to promote young, new, or forgotten talent.

DBIn fashion we’ve seen many crossovers with art—an obvious example is what Gianni Versace did with Andy Warhol—but I haven’t seen as much emphasis put on crafts or handiworks or textiles as you do. Why was that a big deal for you?

JAOne of my fashion heroes, whom I’ve never met, is Issey Miyake. Since the early ’80s, Issey Miyake, through his work, has promoted people like the potters Dame Lucie Rie and Jennifer Lee; he’s been looking at craft and thinking about how his platform could promote it. I’ve always been personally interested in doing that too, so how could I, with a brand based on the art of making bags by hand, give a bigger audience to an artist who makes amazing ceramic bowls or glasswork? I wanted to give more exposure to craft as a discipline and at the same time increase people’s knowledge of it. Craft has had this odd connotation that it’s not contemporary art, but I think, in today’s world, we’ve broken down all these barriers. When you look at people like Lucie Rie or Hans Coper, their works are sculptural and they’re just as important as sculpture. When I look at a Coper, I think it can be just as powerful as a Giacometti.

DBWhen you told your bosses at LVMH that you wanted to create a prize for crafts, what was their response?

JAThey were incredibly supportive. I should mention that Loewe has had a foundation for poetry since the 1980s, awarding one of the most important prizes for poetry in the Spanish language. [The Fundación Loewe’s poetry prize, the Premio Internacional de Poesía, was established in 1988 by the foundation’s president at the time, Enrique Loewe, together with the poet Luis Antonio de Villena and the editor Jesús Visor.] So with the Craft Prize I hoped to add another rung to that foundation and then not even stop there. We’ve done things outside of craft too, working with people like the artist Anthea Hamilton when she did the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain. We helped her make the costumes that she wanted. The Foundation is an evolving thing, and yes, it’s got the word Loewe in the name, but for me it was where we could put money and support into something more detached from the brand. It’s got its own team, it’s got its own thing. And I think it’s very important today. We’re seeing this throughout the world: brands need to be able to recognize their cultural responsibility. For Loewe it was about protecting artisans, the people who make these things.

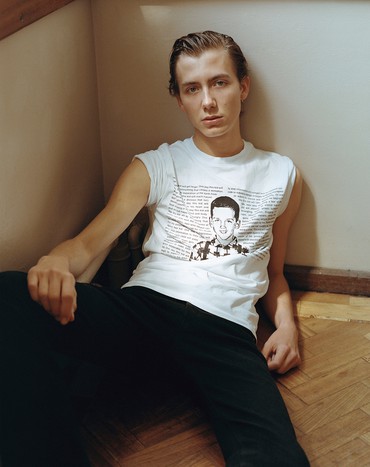

DBI know that you started your eponymous brand, JW Anderson, before you started working with Loewe. Talk to me a bit about your process and how fine art informs what you do.

JALet’s take David Wojnarowicz. I’ve been obsessed with him since university. He was like a gay icon to me. When I was conceptualizing the identity of what we were trying to build as a brand, I thought Wojnarowicz’s burning-house image [1982], for instance, would complement but not overpower the general attitude of the guys we were hoping to dress.

DBHave you ever seen Matthew Lopez’s play The Inheritance [2018]?

JAYes.

DBFor some reason, when you mentioned Wojnarowicz’s burning house, it reminded me of the house that appears at the end of the first act.

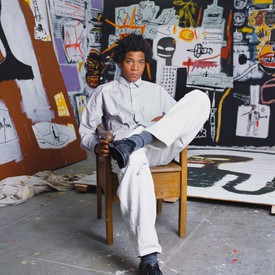

JAWhat’s fascinating about good art like Wojnarowicz’s is that it will always conjure something. Whether it’s about politics or the aids epidemic or Vietnam, when art is very good it will hold its political value in different periods. It doesn’t matter if it was done in the early ’80s, it’s still relevant today.

DBYou do much in the queer art space.

JAWell, I am queer.

DBWait! You are?

JA[Laughs] I like the relationships in that space. Peter Hujar with David Wojnarowicz. Then you have Paul Thek—all of these interesting dialogues. Look at Paul Cadmus, George Platt Lynes: they’re in different time periods but the support mechanism is similar. It’s like defiance through art. I like the romance in it. Sometimes I struggle with blockbuster art because I feel like I can’t find the romance. I like digging into movements of people. Think of someone like Tom of Finland: he comes out of World War II, does these images that birth a clothing movement, a queer-culture movement, a very provocative aesthetic, and at the same time you have people like George Platt Lynes taking incredible pictures in the ’40s—like, incredible pictures.

DBIt took me a long time to come around to Tom of Finland’s work as an artistic movement. I was such a prude, I always wrote it off as pornography or fetishism.

JAIt took me a long time to get my head around Tom of Finland, too. I remember many years ago I bought two drawings that had been a gift from Tom of Finland to the owner of a cinema in Glasgow. They came up at auction. What I found so amazing about them is, he was the most incredible draftsman. If you look at the level of detail in there, those drawings are incredible—they come to life and they’re ultimately about storytelling. When I fall in love with something I get very obsessive about it. One of my all-time favorite historical artists is Paul Thek. I struggle to think how people like Damien Hirst would exist without Paul Thek.

DBOften, for me anyway, legitimizing fashion in the eyes of contemporary-art people can be a daunting process. Does it ever come up in your process, or when you’re working?

JASometimes I do get scared that we’re not going to do the art justice, but that’s my only fear. Over time, I’ve started to develop a barometer of when is the right moment and when is the wrong moment, because you have to give it space—sometimes it’s better to support an artist than to work with them.

DBI don’t know a lot about Paul Thek’s work except this one series called Diver [1969–70].

JAI love that series. It’s all painted on newspapers and then suspended between sheets of glass. One of his most famous series is the Meat Pieces [1963–66], which look like slabs of meat set in tanks—those are what remind me of early Hirst. I’m always looking at precursors. What I love about the art world is that you’re able to be referential and that’s okay, because that’s progress.

DBIs it hard to be referential in fashion?

JAIt’s harder because we haven’t built a culture of reference. I think it’s good that Hirst goes back to Thek’s meat idea: when I think of Thek’s slabs of meat with flies on them, I think of Hirst’s cow head with flies, and of the progression of an established idea with a different viewpoint.

DBWhereas in fashion, if you re-create something you’re copying.

JALook at Andy Warhol re-creating the Mona Lisa. And don’t forget that Robert Rauschenberg was screen-printing too. In art, ideas are cumulative, whereas in fashion I think they can sometimes be combative.

DBTo be candid with you, before I came to the Loewe Craft Prize, I never thought much about the relation between fashion and craft. Was that sort of the point?

JAI don’t think it was intentional in the beginning, but I’ve seen the support mechanisms the Craft Prize has given to craftspeople and I think it’s really brought craft into consciousness. Edmund de Waal has done something similar. I’ve met Edmund several times. We used to have a store in Ibiza and he did a show at the museum there; I also remember that when I was at university and was collecting ceramics, across the road from the British Museum there was a little ceramics gallery that was selling some of his small, domestic pieces. That’s when I first bought his work. Years later he did a talk for us and I could see his contributions in terms of the ceramics landscape. Now, with Gagosian, he’s really transformed craft into contemporary art. He took a massive step, and it’s blurred this boundary, which I think is good because it’s in the blurring of boundaries that I think you find excitement now. A lot of amazing textile artists have cropped up in the last ten years.

DBIt’s nice to see the lines blending, merging, seeping into each other.

JAI did a show [in 2017] at the Hepworth Wakefield [museum in Wakefield, West Yorkshire] called Disobedient Bodies, and that was the moment when I started to fall in love with the idea of breaking down barriers between architecture, contemporary art, dance, and theater. I tried to put everything onto a creative map with no hierarchies between fashion and contemporary art and ceramics. When I did that show, one of my all-time favorite ceramicists, Magdalene Odundo, did these incredible vessels. I was obsessed with how they crossed into this bodily form—they look like they’re alive. There’s something about making something with your hands in coil format. They’re quite physical pieces. But yeah, she is a hero of mine.

DBYou’re doing a service to this art form.

JAA lot of people maybe ten years ago weren’t really thinking of craft as art, or giving it creative merit. What I hope is that through talking about it more, and with the Loewe Craft Prize and what I do with JW Anderson, we’re shining a light on it. Tapestry can be as powerful as painting. There was a historical period where tapestries were considered one of the highest and most expensive art forms. Look at the tapestries Raphael designed for the Sistine Chapel.

DBYou’ve been to the Cloisters in New York, haven’t you? With all those great unicorns?

JAYes, but not recently.

DBWell, there you go. Next season?

JAUnicorns. Done!