Gillian Jakab is an editor, online and print, of Gagosian Quarterly and has served as the dance editor of the Brooklyn Rail since 2016.

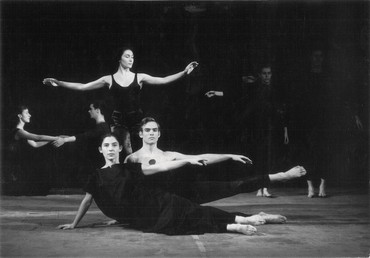

Aileen Passloff’s journey through dance was uncommonly long and wide-ranging. A choreographer and educator as well as a dancer, she maintained a career spanning seventy-five years and the genres of ballet, modern, and postmodern dance. Her joy in movement lit up the lives of countless colleagues, students, and audiences. Passloff’s passing in November 2020, at the age of eighty-nine, drew an outpouring of tributes from around the world.

Passloff’s work flowed with the artistic currents of New York. Born in the Bronx in 1931 and raised in Queens, she studied as a girl at the School of American Ballet, expanded her interest to modern dance at Bennington College, and then, after graduating, flourished in New York’s avant-garde scene of the 1950s and ’60s, for part of that time as a member of the pioneering postmodern collective Judson Dance Theater. Passloff reveled in these radical communities, but unlike her more renegade peers, she also revered the traditions from which they broke. Dance critic and historian Sally Banes writes of her, “Some of her dances are . . . nostalgic tributes to great memories of ballet, or folk dance. Others were resolutely modernist.”1

There was no containing Passloff’s artistic curiosity. She studied flamenco in Spain, winning a Fulbright to research there. Her love of the stage extended to the theater, where she acted in plays by the Cuban-American playwright María Irene Fornés, an Obie-winning production of Gertrude Stein’s What Happened, and others, and even to film, where she made an appearance as a dancer in Stanley Kubrick’s Killer’s Kiss (1955). Passloff ran her own company for a decade before she became the L. May Hawver and Wallace Benjamin Flint Professor of Dance at Bard College. She taught there for over forty years, inspiring generations of students, many of whom would become lasting friends and collaborators. One, Charlotte Hendrickson, recalled Passloff choreographing for her up until her last days: “the creativity and love of life just burst out of her,” Hendrickson told me in a recent phone call.

In early 2020, before the covid pandemic struck the city and made such moments impossible, I visited Passloff one morning in her Upper West Side apartment. Surrounded by the Abstract Expressionist paintings of her sister Pat Passlof—who decided to live her life without the final “f” in Passloff after finishing a painting only to realize that there wasn’t enough room for her full signature—and brother-in-law Milton Resnick, we flipped through binders of photos and program notes, chatting about her lifelong love affair with dance.

We got rid of the boxes, so there were collaborations between people, and not for money and not for fame—just to make something that was worth looking at or listening to.

Aileen Passloff

Gillian JakabWhen did you begin dancing?

Aileen PassloffWell, I’ve danced forever. There isn’t a time that I can remember when I didn’t dance, from before school, before kindergarten. Dancing’s like breathing: it’s as much a part of being a person as laughing and crying and screaming and the rest of the things we do. But I began studying formally at the School of American Ballet [SAB] when I was thirteen.

GJYou’re a fellow native New Yorker.

API am. Where is your family from originally?

GJMy father was born in Hungary and his family escaped to the States when he was young. My mother’s side came over from Russia but have been here a couple more generations.

APMy ancestors are Russian-Polish and Polish. My grandmother on my mother’s side came over when she was eleven, and she was the oldest of her siblings. I always wanted to get stories from her. She was so glad to be in this country; she only spoke in English even though her English was poor. She went to work when she was eleven so that the younger siblings could go to school. And then she became a peddler, selling woolen goods and threads and things like that, because in those days women made their own clothes. And she traveled down south to Georgia by herself, and put six kids through college, without ever having been to school a day in her life.

GJWhat a strong and giving person.

APShe loved life. She’d get a kick out of taking a walk and seeing grass and bugs and birds and all this stuff, and we’d giggle and laugh together. I loved her a lot.

GJFinding joy in the everyday! It’s inspiring to look back at our ancestors and all they’ve given us.

You came from a classical-ballet training, uptown at SAB, and then became known in the experimental downtown dance scene. When did you discover these different forms?

AP My background was very strictly Russian classical ballet. I had never seen modern dance before I went to college [in 1949] and I thought it was weird. I thought, What are they doing sitting on the floor and wiggling? The teacher would say, “Revolve around your soul and get into your groin,” and it was [Martha] Graham stuff. I didn’t even know what Graham was. I just picked Bennington College because it was the best for dancing, but I was a fish out of water when I arrived.

GJWere there particular dance artists who inspired you along the way?

APJimmy [James Waring] was so instrumental throughout my life. We were both at the School of American Ballet, along with David Vaughan and Vincent Warren. Jimmy did everything—he taught and made costumes and collages. Jimmy was about opening doors. At the time, modern dancers and ballet dancers sniffed at each other.

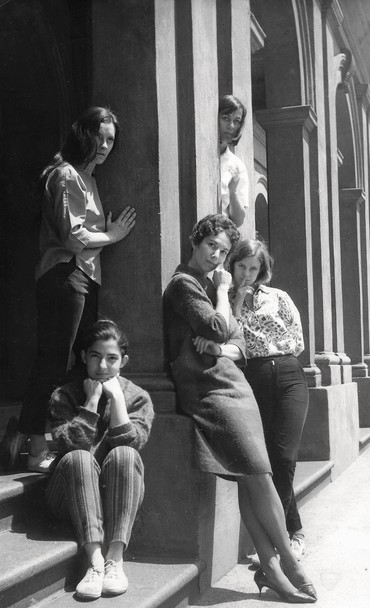

Jimmy and David were very close friends for many, many years, friends at SAB and maybe before that. Together they made a group called Dance Associates [in 1951]. I remember the meeting of that group, and that Edwin Denby was there, Tanaquil Le Clercq was there, Paul Taylor was there, Marian Sarach was there, and Alec Rubin was there.

GJMajor figures in both classical and modern dance, writers—

APThere were musicians there also, so it wasn’t that separate thing, “I’m ballet, I’m modern, I’m a painter, I’m a poet, I’m a whatever.” It was just about making stuff that was worth looking at—that meant something, you know? And it wasn’t for success, and it wasn’t for popularity—it was for the deep satisfaction of making something new.

We all gathered in Jimmy’s apartment, 131 Avenue A. He lived in a little house that was behind the regular house. It didn’t even have pictures of radiators [laughter]. It had a shallow fireplace, and there was a plank that we kept pushing into this shallow fireplace—we all sat there with our coats and our mufflers and our hats. It was the richness of extraordinary people, extraordinary minds. It was so exciting to be in those moments.

GJI bet!

APIn those days, that was remarkable: to be friends with people who were in different boxes. We got rid of the boxes, so there were collaborations between people, and not for money and not for fame—just to make something that was worth looking at or listening to.

GJJimmy Waring’s mentorship and friendship spanned from the very beginning of your dancing days, to your Bennington years, back to New York, and beyond.

APThe first piece of Jimmy’s I ever worked on was called The Wanderers. It’s about a circus family and is performed by a mix of actors and dancers. That was at the 92nd Street Y when I was thirteen. A program of my dances was presented at the Y just last year.

To be dancing at eighty-eight is another thing, but it’s nifty. Nowadays I can’t get up and show too much—I mean, I have to use words in a way I never did.

GJThat’s amazing. I love that you’re still performing.

APThat’s gone on and on, because dancing is forever.

I talk about Jimmy because he was so important in my mind—he deeply changed how I thought and still think about dancing and many other things. It was Jimmy who taught me about electronic music. I didn’t know my ass from my elbow when I met Jimmy. It’s the truth; I didn’t know anything. I mean, I loved dancing with my whole life, my whole everything—that I knew, but everything else I didn’t know. I was really a newbie. But he took me to listen to the music of Richard Maxfield, a wonderful electronic composer. Richard would edit the performance tapes of Merce Cunningham, so he would cut out the rustling of the paper, whatever sounds didn’t have to do with the music. When he’d finished doing that, all the coughs and the sneezes and the paper rattlings would be on the floor, so he picked them up and made a piece called Cough Music, which I choreographed Cypher (1960) to. I began to hear things in a way I hadn’t before because of Richard. We worked with wonderful composers, wonderful musicians—Philip Corner, John Herbert McDowell, just super, super people.

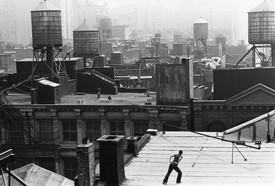

GJWhat did it feel like in New York then?

APIt was an extraordinary time. I don’t think I’m exaggerating. There was no money around, so there wasn’t any kind of competition, because you never got paid anyway, and you even helped to make the costumes or you found them in your auntie’s closet or in a garbage can.

When money got into the picture, things changed. The first time I noticed this turning point was a big concert at the Armory. I went, and the person taking tickets said, “Oh, are you here to steal?” Meaning not to steal money but to steal ideas. I was so shocked; I couldn’t believe it. It had always been about working together. I was going to see my friends’ works, which I still loved, it was Yvonne [Rainer] who was doing stuff, as well as other people I knew and had worked with and cared about. I have to say, it was as if I had been hit in the stomach or something. I realized that things had changed radically. It began to matter if you got paid for a job or if you didn’t get paid for a job. But luckily there were still some people who remembered why we did what we did.

GJBefore being a member of Judson Dance Theater in the 1960s, you were involved with the Living Theatre in the ’50s, where you acted and directed plays. That was another hub where writers, poets, painters, and dancers mixed. Like the relationship between your fellow SAB dancer Vincent Warren and Frank O’Hara—

APVincent had a very quiet presence, and so did Frank. He was so unobtrusive, Frank. I can’t remember whether I directed a play of his for Living Theatre, or if I was in the play, but it had something to do with Nick Cernovich, a brilliant writer and lighting designer who married a dancer. He was full of ideas and was friends with Frank. It was at the Living Theatre that I met Larry Kornfeld, too. The first thing I did with him was Leonce and Lena, by [Georg] Büchner. He also did a [William Butler] Yeats play there, Full Moon in March. And he directed What Happened, the Gertrude Stein play.

It was such an interesting time for painters as well. There was 10th Street, you know, Bill de Kooning was there, Elaine de Kooning, all those people, Milton Resnick was there, my sister Pat [Passlof] was there. Black Mountain was so important to those people. It was also about collaboration. I wasn’t at Black Mountain, but it seemed to me, from the outside, people just had fun together. You want to make a play? Okay, so somebody who wasn’t used to acting would be acting, somebody not used to designing would be designing, you know—whether we’re talking about Judson or Black Mountain, it’s just the freedom to experiment, to dare to do things. Black Mountain included Buckminster Fuller and my sister and Merce and Katie [Katherine] Litz. Do you know her?

GJNot too well.

API have to tell you a tiny story about Katie Litz. She came up to Bennington for one semester, and I was working, trying to make a dance, and at that time I thought making a dance had to do with suffering and going into your soul and all this shit. So, I was busy suffering [laughter].

In the room where Martha Graham made Lamentations (1930), which is a round room overlooking a sunken garden, there I am by myself. And I’d been in there for hours, you know, pinching out one movement, and Katie must have heard me suffering loudly. She knocked on the door and she said, “What are you doing?” I said, “Trying to make a dance,” in a real snotty voice.

GJ[Laughs]

APAnd she said, “What’s the first movement?” I said, “Well, that’s the first movement.” She said, “And what comes next?” And I didn’t have an answer. She said, “Well, it’s just putting one movement after the other.” And it blew my mind away, because that’s when I learned what choreography was: putting one thing next to the other.

GJ[Laughs] So simple.

APIt’s more than that, in truth.

GJBut her point was to not overthink it.

APYes, and that was—thunder, lightning, earth-shaking to me.

Katie choreographed a version of the Dracula story in which Dracula was played by Charles Weidman and Remy Charlip was the doctor—hot stuff all the way through. I was playing the maid and Katie was showing me what to do. Her studio was in Brooklyn, and I didn’t know Brooklyn at that time from a hole in a wall. I once asked her, “What dances are you going to give in this concert that you’re getting ready for?” She said, “Depends on my elbow.” She believed in that kind of physical memory. And of course I got it, but it took me a while to register what she was talking about. It wasn’t that her elbow hurt, it was that sensation guided her: an indication of where she was coming from. I was lucky enough to have learned from her and to have had that experience dancing for her company.

GJAnd you, in turn, have taught and inspired generations of dancers in your company, at Bard College, and elsewhere. What have you tried to teach them?

APWhen I teach, I ask students, “What does that feel like?” Because they may be extremely technically skilled people but they haven’t been taught to listen to their instrument [gestures to her body]—what they use to communicate something. My job as a teacher is putting different people back into themselves, so they can feel where this hand is in relation to this knee, so they know that there’s a little draft coming from there, that there’s a smell in their kitchen. I remind them to use their antennae. It’s natural for us to have antennae; dogs and cats have them too. But we get a little caught up in the visual appeal of dancing and we forget to trust our own sensation.

Dancing doesn’t have to be about notions of success. It has to go back to what you’re thinking about, what you’re feeling—your relation to the world and the people you live with and the animals around you and the flowers you look at. It’s so much more human.

1Sally Banes, Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1987), p. 8.