Fiona Duncan is a Canadian-American author and organizer and the founder of the social literary practice Hard to Read. Duncan’s debut novel, Exquisite Mariposa (Soft Skull Press), won a 2020 Lambda Award. She is currently developing a narrative biography and critical study of the transdisciplinary American artist Pippa Garner.

Cecilia Pavón was born in Mendoza, Argentina, in 1973. She holds a BA in literature from the Universidad de Buenos Aires. In 1999 she cofounded the independent art space and small press Belleza y Felicidad, Buenos Aires. She has published poetry and short stories in Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, and Chile. As a translator from German and English into Spanish, Pavón has translated Diedrich Diederichsen, Chris Kraus, Dorothea Lasky, Ariana Reines, Werner Schroeter, and others.

Fiona Alison Duncan How was your day?

Cecilia Pavón It was nice, because my son started school after one year. Now, I think little joys, like the title of my book, will mean more to people. After the pandemic, every small thing, like going to school one day, makes you happy.

FADIt’s true. We’re recalibrated to gratefulness—resensitized, maybe. I can’t imagine being a teenager right now, because they have so much energy and they want to explore and experiment. Whereas, I don’t know about you, but I can be inside, because I have a solitary practice. I’ll just write and read and talk with people on the phone, and that’s okay for me.

CPYes, for me it’s okay to be at home, because I teach these workshops via Zoom, and it’s fun. It has saved me during the pandemic. But still, I think there’s a limit to screens. It was exciting at the beginning, now it’s too much. The best thing is, you have time to read. Writing, not so much. Because for writing I need the world, the outside, movement. So this idea of staying quiet in the same place—for me it’s the opposite of poetry.

FADRight. I get that impression from your book and your other writings. It almost reads in real time, like you’re writing while you’re out in the world. I picture you with a notebook—simultaneous with living. It has that immediacy.

CPYes, that’s what I’m searching for. That’s been my aim in life, my motto: writing while you walk.

FADThere are many references to plastic and to different disastrous climate situations, floods and whatnot, in Little Joy, particularly in the stories “Types of Plastic,” “A Post-Marxist Theory of Unhappiness,” and “A Perfect Day.” What do you think about the need for poetry and literature to speak on that issue—the responsibility of poets, writers, and artists to use their creativity to think of solutions and raise awareness of the climate crisis?

CPIt’s something I think about every day. For me, it’s not the topic of climate change in “ecological” art that’s important, but rather a total change of consciousness regarding what art is, what capitalism is, what this system we have is. I can never stop thinking about consumerism, how our subjectivity is constituted by buying things all the time. I mean, the economy is based on producing things that we don’t need. But I don’t have any answer. What I like to say is that poetry is a way to deal with reality, and that when the ecological catastrophe comes—if it comes, there are so many possible endings—poetry will help us deal with the change of life.

When I was a child, growing up in the 1970s and ’80s—before neoliberalism came with all its excess to South America; prior to that they had social-democratic countries—I only had one pair of shoes a year, stores closed at midday on Saturday, and there were two brands of cars. Why don’t we stop there? Why do we need more and more and more? I want to hear your opinions.

FADI think a lot of humans have a hard time reckoning with anything beyond what’s immediately present to them, whether that’s understanding a different country’s point of view and how it could be to live with only one pair of shoes a year, if you haven’t had that, or planning for future generations. That’s not part of at least the culture I was raised in, which prioritizes short-term thinking, profit turnaround, immediacy, the next pleasure, the next thing. And that’s quite toxic in the ways that harm gets reproduced and passed down and then accumulates. But I don’t know if we’ll reckon with the climate crisis at a popular level until it’s really, really here, unfortunately.

I was reading an article about [the social scientist] Silvia Federici in the New York Times, and it made the point that her ideas of emotional labor and wages for housework are now becoming popular among a more elite and mainstream demographic because of covid. A ruling class who can no longer get their domestic labor taken care of by, for the most part, Black and brown women—I’m talking about in the United States—are now having to reckon with the reality of that work. Celebrities are making statements like “Moms deserve to get paid.” All these ideas that were once in a socialist feminist space are now getting into a capitalist feminist space. And of course Silvia Federici, and many other people, had been warning about this for so long: we cannot have this mass of labor, of energy expenditure, not be recognized and not be valued. The Times article felt like too little, too late.

CPHere in Argentina, of course, Federici has had a large readership. The ideas in her book Caliban and the Witch [2004] were very important. If we know that we can’t go on using and using and using all the resources, when can we say, Okay, enough?

Poetry, for me, has to do with the past in the present and the future in the present, so I think it’s a place to consider instabilities. What will happen when everything gets to that tipping point? We’ll have to have another organization. It’s not the one we have today—a family, a house, et cetera.

FADYes, I feel like poetry, and especially how you use it, is about insisting on the value of decay, or the value of the broken. It’s about the value of everything on an equal plane, witnessing all of reality, and that’s so different from this capitalist system that says, This is valuable, this is not valuable, this is hot now, this is not now. Poetry is like consecrating the everyday with meaning, which is a coping mechanism . . . or just the way we should live.

I want to know more about the sociopolitical and geographic context of Little Joy and your writing. Often, on the back of your books in English translation, they’re placed in terms of the “Generation of the 1990s” and the economic crisis of 2001. But American readers might not understand what that means to you and how it impacted your writing practice.

What I like about translation is this intimacy with the text. For me, it’s a trip. It’s as if the ideas of this author come to your brain in a way that can only happen if you translate them. It can’t happen just by reading.

Cecilia Pavón

CPWell, Argentina had a dictatorship in the 1970s, like most Latin American countries, of course promoted by the CIA. Everybody knows it today; the files must have been declassified years ago. The International Monetary Fund lent a lot of money to the dictator. With this external debt, the economy was very hard to cope with, because it was always paying interest. Then we had democracy restored in the mid-1980s, but that ended in 2001; the external debt was impossible to pay, there was a big crash of the bank system, people couldn’t take their money out of the bank. This was something that happened first in Argentina but later happened in many countries, like Iceland. We were kind of pioneers of the crazy neoliberal order of the world that has now made itself known everywhere. Here, we’re used to this oscillation of the economy, of crisis, but it’s also what’s happening in the United States, in Europe, with the impoverished middle classes. It’s impossible to be an Argentinian writer and be distracted from this economic crisis. It’s the way the world is: in crisis. I don’t know where they don’t have crisis.

FADYou have a head start in understanding that.

CPYes.

FADThe “Generation of the 1990s”—is that a term you like?

CPIt’s a term used for a group of poets. It’s also an aesthetic in poetry that was originally an innovation in the poetry of Argentina; it’s highly valued in Spain, too. It had to do with experimental poetry related to letting other materials in: rock or pop or politics, not just the literary tradition. There’s a famous phrase by the poet Martín Gambarotta from the 1990s that goes “My classics are my contemporaries,” something like that. I was part of this; when I was young, I was always related to a lot of writers. There was a big community.

FADWas it a label that you and your peers embraced, or was it put on you by critics?

CPBy critics, but people embraced it. It was really something new in poetry, in literature. Maybe there’s a correlative in New York, like Eileen Myles and her friends—for me, it’s similar to the idea of poetry that Eileen Myles has.

FADI’m curious what you think that idea of poetry is. It’s embedded in life?

CPI know in New York there was this language poetry, very formalist, intellectual, and then there was a poetry that was modern, new, rejecting the academic idea, bringing something conceptual to poetry coming from rock, from pop, and also from tradition. Those were the voices of the 1990s here in Argentina, and with time they became important for all of the Spanish-speaking countries, because we have this particular thing in South America and Spain, which I love: every country has its own Spanish and its own tradition, but there are always dialogues, an exchange of ideas, among different national communities. It’s very interesting in that sense to be a Spanish-language writer—I love it.

FADAre there authors who are famous or popular in Argentina but don’t have international acclaim or aren’t being translated, and vice versa? How do you feel about being translated and read internationally?

CPWell, of course there are great authors here from the past and from the present who haven’t been translated. But Spanish is a widespread language, read in many countries, so it’s not like being an author from the Netherlands. Even if they don’t translate your work, you can always find an audience in Spanish. There are writers here who nobody knows, and maybe you go to Colombia and they tell you, Wow, there’s this Argentinian writer I love, and you say, Ah, I’ve never heard of him. It’s interesting, this traffic between different audiences within the same language.

I’ve loved languages since I was a child, but in my home, nobody spoke other languages. All my grandparents and great-grandparents were from Spain, and when I was a child, I started asking my mother, Please, take me to study French. When you love books and poems, you love languages, too, because other languages are the essence of literature. I mean, to read a foreign language is to be constantly surprised: Wow, they use this word like this.

I’m really happy being translated; it’s lucky that I can be read in other cultures and contexts. I’ve learned a lot from how people read my pieces in other places, they have perspectives I’d never thought of. When they translate your text, you learn something new about what you wrote.

FADYou also work as a translator; what attracts you to particular texts in order to translate them?

CPTranslating always has to do with how interesting the author is, you know? The first book I translated was by Diedrich Diederichsen, from German. For me it was always about admiring writers, making new friends. I want to translate this guy because he’s interesting, and if I translate him, we’ll be friends in some way, reading his book.

And that happened with English when I started reading some authors who interested me. Around 2010, I read Dorothea Lasky, Ariana Reines, and other poets. I felt there was an affinity there with what had been done in Buenos Aires in the 1990s, at least by women. Then I started translating more English, and now I only get English books. Because I do it as a way of living, it can be very exhausting. I translate less now but I’m currently translating Claudia Rankine and at the same time, I’m translating Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own [1929]. It’s so different, the English from England—and also the interior view Virginia Woolf creates; that book is very full, but it’s very interior. What I like about translation is this intimacy with the text. For me, it’s a trip. It’s as if the ideas of this author come to your brain in a way that can only happen if you translate them. It can’t happen just by reading.

FADDoes it affect your writing?

CPWell, for one, I have less time. That’s why I write very brief texts, I think—I’m a mother and I have to work a lot. But really it affects me because translating gives me ideas when I write. Finishing a short story after translating was something I liked, and probably one or two things passed into my story.

In my view, art is a tool for relating with others, not for your narcissistic exhibition. And I definitely believe that this solitary genius, this solitary monster, is a thing of the past.

Cecilia Pavón

FADAriana Reines, in her introduction to Tiqqun’s Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl [2012], talks about translating that text from French to English as an act that made her physically sick, and that book generally can make you sick if you haven’t been exposed to something like it—it can cure you but it’s almost like you need the vaccine that contains a small dose of the illness, and there are side effects. Have you had psychedelic-like or mood-altering experiences with translating?

CPWell, for me, it’s the psychedelic craziness of thinking you’re in the person’s mind. I used to know the term in Greek, something with ψυχή, with soul—I think it’s “out of your soul.” It’s the closest I come to a psychedelic experience.

FADDo you ever write in English or German first? Do phrases in a second language ever come to you?

CPGerman is a language I have almost abandoned, and I regret this, but of course everything is becoming more and more in English, even in Germany. So many people in Germany write in English. But yes, I do, but not with the pretension of being literary, more like a game or a job; I could never write a poem in English because it’s not what I hear in the background. Maybe if I lived in an English-speaking country, but now, no.

FADWhy don’t people translate their own work? It’s so rare.

CPBecause to achieve the mother tongue is very hard. I couldn’t translate something into English. It doesn’t sound so natural, for literature. Maybe something more technical, yes, but poetry—that’s why it’s so important it’s a literary translator, because they have the sensitivity of the work.

FADRight, the rhythms and all of that. There are references to noise in your book. The stories evoke music and poetry as noise and the city as noise. I’m hearing noise in the background now, so I wanted to ask about what writing has to do with noise.

CPYes, I think when I was starting to be a reader or a listener or a culture consumer—I hate the word “consumer”—but it has to do with being in an attitude of hearing. You say, Okay, I’ll stop and open my ears. Also, here in Argentina, Buenos Aires is a very noisy city in general. Compared, for example, with Germany; when I came back from Berlin I couldn’t bear it here. It’s one of the noisiest cities in the world, Buenos Aires.

FADWhat kind of noise?

CPCars. Cars and construction.

Noise, it’s a good question—see, this is what I mean when I say that when somebody reads you in another linguistic context, they bring you something new. Nobody has asked me that question before; I hadn’t thought about what noise is. It has to do with this idea of paying attention to surroundings.

FADWhat’s the newest story in Little Joy, and what’s the oldest? What’s the timespan of the different stories? I noticed they aren’t dated.

CPThe oldest one is the one that’s about nuns—

FADOh yes, I liked that one.

CPIt’s talking of a world without men. I wrote it after reading SCUM Manifesto [1967], by Valerie Solanas; I remember I read that when I was in my late twenties. And the last one is “Types of Plastic,” which I wrote one year ago. I haven’t written a story in the last year, because, well, I told you that it’s really hard for me to write in the pandemic. I write only poems. I think it was the translator, Jacob Steinberg, who suggested not dating the stories, and I thought it was a good idea. In general I like to think there’s no time, no biographical time, no historical time. I like to think of the moments that escape time: the first, heroic moment of house music, when the beat drops, in an open-air party with thousands of people dancing. There’s no time when you’re dancing to this kind of music and this ecstasy. For me, this feeling of music was so important in my life, and so I think I don’t care about historical time or biographical moments.

FADYes, you get that sense in the book also. It feels like parts of it could take place in America right now, the stories that are less fixed in either space or time. But other stories seem futuristic. “The Post-Marxist Theory of Unhappiness” reads like speculative fiction or science fiction—at first it seemed very present to me, and then I realized that certain claims to technological advances or climate disaster had not yet reached their peak in our present. Rather, they’re things we fear, or that maybe are happening in little bits right now but are not as widespread as in that story.

CPI’d never say I’m a science fiction writer, but more and more with time, I realize how important science fiction was, is, for my generation. My mother was a fan of science fiction books. My house was full of them. My father read “real literature,” “high literature,” like Dostoevsky or Borges. With him it was always, This is science fiction, it’s not real literature. But I’ve realized how science fiction influences our imagination and I’m starting to read it more. Today the world is kind of science fiction [laughs]. It’s Elon Musk, NASA going to Mars.

FADThe world definitely feels like science fiction. My next book is quite science fiction-y; that’s just what’s in my brain right now.

CPWhat’s it about?

FADParts of it are about female reproductive technologies—childbirth, menopause, the menstrual cycle, hormones, all that stuff—and people coping with inaccessibility to health care and services.

CPYes, it’s a major consideration in the present, and I’m curious how children will be born in the future.

FADThe reason I don’t read many science fiction books is, they’re often poorly written—the language is clunky. Do you need to read things that are beautifully written?

CPYes, totally. I don’t know if beautifully written, but graceful. Sometimes science fiction takes such a nineteenth-century idea of structure. The characters, the psychology, they’re not crazy enough in form for me. But this year I read Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower [1993]. It has poetry in it.

FADYes, she was embedded in a science fiction world and tried to play by some of its rules, but she has her own poetry. There are constraints to the genre: the robustness of it, the materiality of it, the way you have to explain. I like writing because you can go inside and outside of people so easily and don’t have to make everything perfectly, visibly clear in terms of the scene. I was trying to write a script recently and found it very difficult, because it’s so “objective.”

CPI have no idea how that happens. I’ve always written poetry that’s in the moment, direct. And my stories are written in a way that’s like a longer poem. Instead of focusing on plot, it’s more like how one thing connects to another.

You’re a person who is not isolated. I don’t see how you say it’s a burden to have a child. For me, I think it’s too heavy to be an individual. Just like in my writing, I prefer to see myself as related to other people.

Cecilia Pavón

FADA few of the stories in Little Joy relate to the idea of the celebrity or popular figure as a tool for other people’s projections. Some people have been willing to let themselves be that mirror. I do think, or maybe I hope, that the idea of what’s celebrated is shifting.

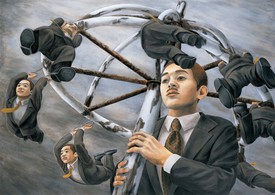

CPIt has to do with the twentieth-century artist and the twenty-first-century artist.

FADYes, that’s what I’m thinking of. There’s a line in one of your stories: “I also had to admit that all twentieth-century artists were kind of monsters, monsters screaming their deformity at the world in high-pitched screams.”

CPYes. For that figure, it’s a wounded narcissism. In my view, art is a tool for relating with others, not for your narcissistic exhibition. And I definitely believe that this solitary genius, this solitary monster, is a thing of the past. It’s from the modern artists. And to use a poem to get revenge—which I did when I was young, now I’m grown up, I don’t do that, although maybe I will again in the future—has to do with using the work of art as something not autonomous. It’s in opposition to the idea of modern art as a world within itself. Maybe it comes from the world of hip-hop, this idea of, I’m always including you, even if it’s to say I’m better than you. That’s the art that I mean to make: art that includes the other. When I was doing these stories, many are messages for someone, whether intended as revenge or otherwise, because it’s fun to read, or necessary. I can’t sit and think of a great plot that I want to write—I admire people who do it, but for me, writing is always a message for someone specific. I think art has to do with relating to others. It’s my utopia, that idea.

FADUtopia’s definitely something that comes through your writing, a sense of projecting a utopia or offering possible utopias.

CPYes.

FADI feel like the model of the solitary genius is also becoming dated because of the Internet. Some of the veils are being lifted on the mechanisms that allowed certain people to become the celebrity; we better understand who was working behind the scenes, who was exploited or ripped off, who was entitled or persuaded to stake a claim.

CPYes. In general they say women’s writing is the “I” literature, but for me it’s the “you” literature. That’s my opinion, my reading.

FADI have read you discussing the degradation of the feminine in relation to poetry, art, and life. This has long been part of the feminist project, asking why women have been demeaned. But we’ve done so much work to decouple biological sex from gender, so that we can talk about femininity as a spirit or an energy or an aesthetic. I came upon an academic concept recently that has helped me give language to this: the term “femmephobia,” which is looking at how the feminine, or expressions of femmedom or hyperfemininity, are degraded and exploited across identity lines. You can look at how femmephobia affects trans femmes, straight men, cis gay men, Black women (misogynoir), and on and on.

I see you employing lots of feminine tropes in your work, whether it’s the “I” that’s the “you,” as you just said, or, I don’t know . . . writing about sparkly jeans. How are you instrumentalizing femininity?

CPThese concepts have changed so much in the last fifteen years. When I read many of these tropes that you referenced, and that I myself wrote, I say, What’s this? I thought so differently when I was twenty-five from the way I do now that I’m forty-eight. I really think it’s kind of an archaeological dig when I read it now, to be honest. It is like the thread of an extinct civilization, this idea of femininity being beautiful or buying clothes or whatever. But I think at the same time, the oppression of women has to do with neoliberalism, in the end, saying females or femininity are not serious, not valuable. I think everything has changed so fast. And I’m happy about that—that people who are sixteen have a totally different range of ideas about gender.

On the other hand, when I’m translating Virginia Woolf, a book that’s almost a hundred years old, I still think so many things that she writes are true and still happen, even with women’s rights. So at the same time, I don’t know if things have changed that much.

One place I see this come up is motherhood. When I was studying at school, all the feminists and intellectuals of the older generation were like, You cannot be a mother. It has to do with the idea of the independent individual alone, and a child is a burden, it bothers you, et cetera. Because again, in the free-market economy, an artist has to be productive. Twenty years ago, it was a shame, it was uncool, for an intelligent woman to be a mother. For me, it has to do with this demeaning of femininity that you mentioned.

But I passed through different stages. I know all kinds of artists with children, and in the end, I think it has to do with the idea of getting conscious that you’re bound to everyone, not only to your child. You’re a person who is not isolated. I don’t see how you say it’s a burden to have a child. For me, I think it’s too heavy to be an individual. Just like in my writing, I prefer to see myself as related to other people.