Victoria Phillips is the author of Martha Graham’s Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy. A visiting fellow in the Department of International History at the London School of Economics (LSE), Dr. Phillips runs the school’s History, Culture and Diplomacy project and is the director of the Cold War Archival Research project (CWAR).

Kon Trubkovich was born in Moscow in 1979 and now lives in New York. His work appears in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, the Hood Museum of Art, Hanover, New Hampshire, and others. Solo exhibitions include No Country for Old Men, at MoMA PS1, New York, in 2006, and Kon Trubkovich, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, in 2015. Leap Second, a monograph on the artist’s work edited by Cay Sophie Rabinowitz, was published by OSMOS in 2015. Photo: Jesse Frohman

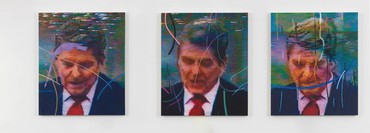

Three images of Ronald Reagan’s mid-profile open on my screen and I’m transported to Berlin 1987. In the midst of the pandemic, the paintings reach me as clearly as if I were standing in a gallery, museum, or studio. Cold War triumphalism is ringing hollow and telling me the story of Kon Trubkovich, although I do not yet know the details. Trubkovich himself is telling us the story of ourselves: I am seeing myself. This is the power of his work. As a student and scholar of the great modernist dancer and choreographer Martha Graham, I recall her consistent call for us as dancers to find “a blood memory that can speak to us,” can bring us from “some deep memory of a time when the world was chaotic” into an artistic creation with the potential to reach across human boundaries. “How else to explain those instinctive thoughts that come to us, with little preparation or expectation,” Graham asked, other than through this blood memory. It is the sense of knowing something instantly, or, for artists, that moment of creation when all is silent and without boundaries. Graham studied under a Jungian, and Carl Jung had given this a name: “the collective unconscious.” Jung also wrote a phrase that better explains it in relation to Trubkovich: “Image is psyche,” he concluded, as though knowing what I know, what we know, seeing these images. And, Jung asked, “Who has fully realized that history is not contained in thick books but lives in our very blood?” Trubkovich knows, and lets us answer Jung, “We do.” By definition, the personal becomes the political and the political the personal. Through Trubkovich’s approach to portraiture, biography, and memory, an abstract embodiment creates kinesthetic experiences: blood memories. From paint on canvas to VHS or film, this is his genius.

—Victoria Phillips

Victoria PhillipsAs a historian of Soviet and Communist history, I’m fascinated by your upbringing. What are your first memories of Moscow?

Kon TrubkovichFor a Soviet childhood, mine was somewhat idyllic. My family lived in Moscow. Anywhere outside of Moscow or St. Petersburg would have been a more difficult place to grow up. On my father’s side my family was artistic: my grandfather was a children’s-book illustrator, and my father too. Then on my mother’s side they were almost all psychiatrists. It’s this witches’ brew that’s my family: on one side they were doctors in the mental-health field, and on the other they were all artists, illustrators, and different kinds of creatives.

Moscow in the 1980s was an interesting time for a kid, because we didn’t have anything Western. Everything was Soviet issue. We were really cut off and shielded, anything from the West was superexotic and novel, so there’s some nostalgia for that sheltered austerity. Today there’s a lot of political maneuvering in Russia to get back to the appeal of that time.

My family members were all university educated and were part of a kind of bohemian milieu. That’s how I grew up. And then, of course, in 1986, Chernobyl happened. That’s when my parents realized they had to go.

VPAnd how did they manage to get out?

KTBy 1990, the trickle became a flood. [Soviet President Mikhail] Gorbachev made a deal, if I’m not mistaken, that involved the easing of borders. The Americans agreed to send, I believe, Pepsi concentrate, and in return the Russians were going to allow the Jews out [laughter], which is absurd.

VPAll these exchanges were made for Pepsi. Pepsi, Marlboro Man, the frontier, and the “Truth” were the Cold War tropes that the US was pushing.

In terms of artistic upbringing, I have a clear memory of the first time I wrote something. Do you remember when you first created art? Or was it just something you always did?

KTAlways, from the very beginning, I was drawing, making things. I don’t remember not making art. In Russia when I was growing up, the [Second World] War was a pervasive theme. The victory permeated almost every childhood propaganda message; for my generation the creation myth of the nation was so infused with winning the war. So all the boys thought they wanted to be a soldier or a policeman. Early on, I thought I was going to draw mugshot pictures as my job [laughs]. I was going to split the difference.

VPDid you go to a specialty school for art, or was art part of the standard curriculum?

KTI wasn’t good at academic drawing, I was just really good at drawing people and kind of getting them right. I did printmaking with an artist friend of my parents, too. I’m glad they didn’t send me to one of the formal academies, because those were really about that old, strict, European pedagogic style—academy drawing, shading of the still life, folds, apples, and bottles. There wasn’t a lot of room for creativity.

A memory I have, the thing that really attracted me to art early on, is my grandfather’s materials. He had his illustration studio in the house, and there were different pencils and erasers and brushes, and everything had this patina, old stuff with paint on it. I wanted them so badly, and sometimes he would gift me some pencil or brush and I would treasure it. I think that carries into my work now in the way I deal with video. To me, it’s a material thing, a temporal thing, something that’s happening, something you can touch.

VPI remember taking film courses as an undergraduate in the old days when there really was film, right, and holding it and literally cutting it—a very physical, material memory, like you described.

KTI’ve worked with actual cellulose film in my videos, where I drew on the stills and played around with them, so I understand exactly what you mean. [Andrei] Tarkovsky talks about this; he has this great book, Sculpting in Time [1984], an autobiography with musings on art, and he talks about film in material relation to painting and how similar they are.

VPForgive me if this is the West’s myth of the Soviet period: I’ve heard from people who came from East Germany over to the West that there was this sense of shock about color—the US advertisements with their saturation, even the yellow of butter, right? It can feel like an assault on the eye, or it can feel like, Oh, isn’t this seductive? Did you have that experience with color?

KTYes, but not only with color, it was a general sensory overload. It’s color, it’s smell, it’s the idea that there’s fruit in winter. I lived in Berlin for a little bit, and some of my contemporaries lived through the reunification. I remember hearing stories of people who woke up, realized they could walk to the West, and ran, because they’d heard there were bananas on the other side. It may seem absurd, but you couldn’t get a banana in winter in Soviet times. So the smell of fruit in the winter, saturated colors, and just the opulence of choice, walking into a mega-supermarket for the first time—it was an insane experience for a Soviet person.

The thing that animates me to make art is a fear of forgetting—a fear that if I forget what all of this is, it will just disappear, and then with it, I will disappear.

Kon Trubkovich

VPYes, I’m just looking at the colors of the painting behind you and thinking about that vibrancy.

KTYes, but Byzantine icons also fascinate me, and the vibrancy of that Russian palette, and the exchange between that and Italian Renaissance—that’s a specific thread in my work that isn’t necessarily tied to the post-Soviet experience. To me, part of the fascination of painting is what a continuum it is from the beginning of human history. Of course my work deals with my own personal history, with trying to understand my sense of displacement, but when I approach painting, it’s as much about collective memory as about personal memory.

VPSo it’s kind of Jungian, in a sense.

KTYes. There’s an internal catalogue that I draw on, and a kind of collective unconscious.

VPI can see the Byzantine, and now that you’re talking about it, there’s that grand Russian tradition—

KTSome of it’s purely Russian, some of it’s parroting Europe—the way Russia integrated itself into the West over the centuries is such a complicated weave. It was cut off by the Mongols, it opened up with Peter the Great, it was again cut off by the Communists, and each time, something purely Russian came out of this strange salad of historical happenstance.

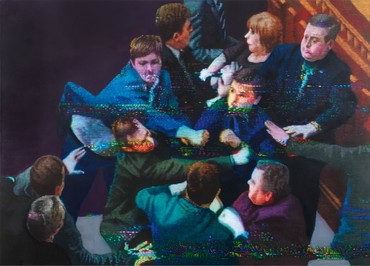

So the other thing is, if we’re talking about formative childhood memories, the Golden Ratio paintings are based on a series of images that I saw pop up on the Internet a couple of years ago, grouped under a series of memes called “Accidental Renaissance.” It’s a picture of a fight, and I recognized the faces as totally Slavic, Eastern European faces right away. I thought, Why does this image grab me?, and as I was thinking about it I remembered, it really reminded me of a painting I saw as a little kid in a book at home, Rembrandt’s Blinding of Samson [1636]. It’s this grand Baroque masterpiece. Samson is super-foreshortened, he’s being blinded by this massive saber, and Delilah is above him with a lock of his hair, which is the source of his power. I was little, I had to have been like four years old, and I was fascinated by the fact that this painting felt forbidden, an image of violence. I remember looking at it and just being absolutely riveted, “Wow, this is what I want to make,” even then. Part of me thinks that’s what made me really want to be an artist—to say, Hey, this is possible, I want to do something like this.

When I saw this fight image online, it brought me back to that memory of the painting. So there’s the connection to a Baroque European tradition, and then, of course, that image, once you get deeper into it, is a fight between Russian nationalists and Ukrainian separatists in 2015. It’s fully the product of post-Soviet chaos and Russia reasserting itself. So there’s that duality: having this kind of intimate connection to an image, understanding how the politics of it affect me personally, and then seeing it through this filter of transmission. My way of making paintings is to retransmit them through this old, archaic, VHS format. When you layer those three subtexts, you get something that’s kind of uncanny, where you don’t know exactly what you’re looking at anymore.

VPYes. Martha Graham calls it “blood memory.”

KTOh, that’s great.

VPI had that sense with Diversion of Angels [1948], her dance piece after [Vasily] Kandinsky, which is also about love—she was channeling something of youthful first love, but it went back through the generations. She’d tapped into something much bigger than a particular person, a particular time.

KTI think that’s art operating at a high level. It’s primordial—you tap into a human undercurrent, that connective tissue between us. It doesn’t happen often, and when it does, it’s transcendent. The thing that animates me to make art is a fear of forgetting—a fear that if I forget what all of this is, it will just disappear, and then with it, I will disappear. Luis Buñuel said, “Life without memory is no life at all. . . . Without it we are nothing.” So video, for me, is also a way to archive, or at least a metaphor for the archiving of these memories, of keeping them internal or not losing them, because the truth is that where I was born, and how I lived, no longer exist. That may be true in some sense for everybody, but it’s really, really true for me and people like me.

VPI was so fascinated by the idea of VHS in your paintings, because I remember videotapes would catch and they made a sound, that hissing. I almost hear the sound and have a physical reaction when looking at some of these paintings.

KTI collect VHS players—I have a dozen of them, different ones, and I use them in the way somebody would use a drum kit.

VPCan you explain that?

KTEach one has its own function—like you use a cymbal and you know what a cymbal does, you use a bass drum, you use a snare, each for different effects. Right before they break, they’re just the best. But I know which ones do what—they have their own affect, patina, attitude—and I dub and redub these images or videos, the material that I’m going to make the paintings with, through these different machines.

VPHow did you first begin working with this material?

KTI went on a cross-country trip in the United States, and I took an old video recorder with me. This was in 2002 or 2003. When I got back, I started watching the footage I shot. When I paused the tape on the TV, a million narratives just shot out of every frame. I felt supercharged all of a sudden. So I thought, How do I make this into a painting?

Lately I’ve been thinking, Why did I have this charged experience with TV? In these new works, I’ve been painting about the putsch attempt of 1991 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, that whole society crumbling, but I wasn’t there to witness it; I watched it on television in the United States. We’re always reliving these strange childhood memories. I think my connection to video footage comes from the fact that I saw that event happening, my old world fade away, through the screen. And through that texture I was able to make sense of it, somehow. It wouldn’t work for me as a photographic image.

So I think of these video stills, and this aesthetic of the television screen, as the physical manifestation of memory, that collective memory, that blood memory, in Graham’s words, which is an amazing way to describe what I’m talking about.

VPThe thing that strikes me there is, a picture is a moment frozen with a click, whereas video is ongoing. Your paintings create a sense of only a momentary pause.

KTExactly. You’re always anticipating the moment before and after with these stills, they’re not static. That’s a play on words, because you see static, but they’re not static in the kinetic sense. There are all these layers of transmutation of the initial video or image, it becomes something entirely different—things break down, things gain. There’s a video I made, my first video, called Repeat Offenders [2005]. It went from digital to VHS back to digital. I’d fast-forward through the VHS, then slow the video down, fast-forward again, slow it down again, and in the end it had completely fallen apart. It was just down to its atoms, this very strange, molecular image, not at all what you would consider a photographic or realistic image.

In a way, that’s how I paint as well. In the beginning, I’m trying to unify the canvas, make it into a whole plane, to play with the color and how it creates space. But once that’s set, the finishing of the painting is very molecular. I’m painting pixel by pixel, replicating the logic of the screen.

VPTell me a bit more about this rhythm and your practice.

KTMy rhythm changes. As I described, the paintings go through different stages. There’s an initial exploration, looking for images, searching, whether it’s on the Internet or through archives or through personal videos. Then something burrows itself into my mind. It takes a long time for me to settle on a painting, settle on an idea, settle on a body of work, but once I do, the images start to coalesce into groups, and then it’s time to work on making them into these video stills. I’m sitting there with machines, pressing play or pause, and I can only do that for a couple of hours, because it’s just pause, click, pause, click—it’s a very mechanical process.

When I start to paint, everything moves very slowly. You put a color down and then just spend days of sitting and looking at it, and feeling alternately useless and excited. That process of looking and beginning to arrange things on the canvas is fraught. The painting is just there and you don’t see the end of it yet, you don’t even have a sense that it’s a thing yet, you’re just feeling for it in the dark.

And then the final finishing process is the detailed painting of the pixels, of the television screen, and that’s eight hours a day of really technical, Renaissance-style work—like those Dutch collars with every little lace detail in there, that’s me all day long, painting that lace collar with a little tiny number-one brush.

These are the stages and they’re all dependent on each other. And each time, the rhythm in the studio changes. I can’t overlap them, somehow, I have to go through the stages, which is why I like to work on several paintings at a time, because otherwise I get stuck on one painting.

VPSo you don’t find your mind going to the next series while you’re in one project?

KTOh yes, absolutely. But I can’t do anything about it, so it’s a bit of torture. The works feed off each other, and if I walk away from the whole project to go do another thing entirely, it feels untethered, and then I can’t even do that other thing, because that feels untethered too. It’s a bit of a psycho-game that I think painters play with themselves.

VPI was really struck by the Reagan trio. It just summed up something for me. How did you come to the composition of that work?

KTWell, he’s reading the Brandenburg Gate speech. He looks down and up; he’s got the speech in front of him. There’s no preconceived reason for the three figures; I made three, and then when I saw them together, they seemed like one work. With the Reagan series I took one second of the Brandenburg Gate speech and painted almost every still in that section. At least that was the conceptual framework for that project. It lent itself to a sequencing of images, so I could have these three stills and they’d feel like a random sequence of the same event.

There were two bodies of work in one: the images of my mother from the last party we had before we emigrated in one second, and in another second the Brandenburg Gate speech. In my mind, it happened simultaneously, these two seconds in time. So the idea was to paint just these two seconds, and there’d be forty-eight paintings in total, twenty-four frames of one event and twenty-four frames of the other. I’ve finished that project, but now sometimes I’ll go back into it and make smaller versions from those stills, and that’s what those three little Reagans are.

VPWe spoke about the influence of art-historical traditions on your work. Do you have favorite painters?

KTThe painters who inform this work are Rembrandt, Fra Angelico, Filippo Lippi, Hercules Seghers, Petrus Christus . . . I looked at a lot of early and high Italian and Northern Renaissance art. Bob Thompson and Per Kirkeby are also very important to me.

VPWhat is it about those painters that attracts you?

KTI’m most interested in these painters specifically in the way they deal with space. There’s another set of artists I looked to in terms of content in relation to this work, including Beatriz González, Doris Salcedo, Leon Golub, Andrzej Wróblewski, Tadeusz Kantor, and Bruce Nauman; from them I drew on ways of dealing with political subject matter, personal or poetic subject matter, historical subject matter. But in terms of painting generally, what I think about the most is creating space. A painting can create space or it can take up space, and I think I’m on the side of creation. That’s why I really love Byzantine art, because its space is so abstracted and yet you really feel life coursing through it.

Actually one of the main influences on this body of work is a film, Sergei Loznitsa’s The Event [2015]. Loznitsa is a kind of artist/archivist who works mostly with found footage. In this case, I don’t know how, he discovered hours and hours of footage of St. Petersburg during the failed coup, the 1991 putsch, and he put together a chronological narrative of what happened, but he did it in an intuitively powerful way. The way it’s edited, the sound—it’s just deeply moving. Some of it had to have been recorded after the fact, but the sound brings you right into the crowds. And the whole time, Swan Lake is playing in the background, because when the putsch started the generals took over the state TV station and just played Swan Lake on repeat all day on all channels.

I saw that movie when it came out, and I was already thinking about the putsch and looking for images, so it gave me agency to take ownership of them the way Loznitsa gave himself ownership of this found footage. It’s almost not even appropriation, it’s more like identification, because you lived it. It’s not just an aesthetic thing and it’s not just a conceptual thing, it really is a reliving of this history.

VPI’ve written about how many of the American modern dancers in the 1930s interwar period were card-carrying Communists.

KTWas that the time of Paul Robeson?

VPExactly, Robeson sang for some of these dancers. They did revolutionary dances and a lot of the dances were done to poems that were written by Communist poets. When I went into the US Communist Party archives, Moscow would say, Now we’re going to talk about hunger and the Depression, and then there’d be a play about hunger, and a film about hunger, and a dance about hunger. So there’s a link, right? And then I showed the way these dancers basically fueled American modern dance. Without the Communist American dancers there’d be no American modern dance as we know it today.

KTAnd without Russian Constructivists, American modernism wouldn’t be what we know today. The project I’m starting to work on deals with paintings that were confiscated and hidden away during Stalin’s purges, because they were considered degenerate art, and then they reappeared in the 1990s but are unattributable, no one can prove their provenance. They don’t know whether they’re fake, if the Soviets destroyed the originals, or whether they’re the real deal. So they’re orphaned, in a sense. You wouldn’t have a [Willem] de Kooning, you wouldn’t have a [Jackson] Pollock, you wouldn’t have a [Piet] Mondrian, you wouldn’t have any of our modernist canon if it weren’t for these artists from Ukraine and Russia, like [Kazimir] Malevich, [Olga] Popova, and Kandinsky, who completely changed the course of art history.

VPThat’s very true. It’s a good parallel. The funniest thing was, they wouldn’t mount my research as an exhibition in the United States because I used the word “Communist,” and this was in 2006. They said, We’ll make this into an exhibition if you call them leftists, and I said, But they weren’t leftists. The Cold War lives [laughs].

KTThe Cold War is alive and well. Getting warmer, I think, sadly.

Artwork © Kon Trubkovich

Kon Trubkovich: The Antepenultimate End, Gagosian, Park & 75, New York, September 9–October 23, 2021