Tyler Mitchell is a photographer and filmmaker who works across many genres to explore and document a new aesthetic of Blackness. In 2018, he made history as the first Black photographer to shoot a cover of American Vogue, introducing Beyoncé’s appearance in the September issue. The following year, a portrait from his Beyoncé series was acquired by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, for its permanent collection.

Antwaun Sargent is a writer and critic. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books, among other publications, and he has contributed essays to museum and gallery catalogues. Sargent has co-organized exhibitions including The Way We Live Now at the Aperture Foundation in New York in 2018, and his first book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, was released by Aperture in fall 2019. Photo: Darius Garvin

Antwaun SargentYour 2020 series I Can Make You Feel Good was about utopia and the ways in which a Black utopia could be imaged through your aesthetic lens. Here, with the new work, you’re engaging with landscape, the idea and the genre. What led you to explore this notion of landscape?

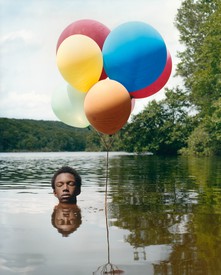

Tyler MitchellI Can Make You Feel Good was a response to the idea of representation. A lot of the images in that body of work are a cross between personal work and commissioned work in the fashion space, so all of those works think more in terms of portraiture, the history of representation, and how I’d like to photograph or imagine young Black folks existing in a fashion context. It was also a response to the work of photographers like Ryan McGinley and Larry Clark. With I Can Make You Feel Good I envisioned new protagonists inhabiting this idea of free youth or utopia—namely, young Black men and women relaxing and enjoying one another. With my new project Dreaming in Real Time, several questions arose: What spaces do these protagonists inhabit? In what spaces do they interact? What is our historical and contemporary relationship to physical land?

I think a lot of that started coming to life for me over the last year, when, due to covid, I wasn’t able to visit Georgia, the land I’m from. I spent a lot of time dreaming about that land in a nostalgic way. The images came from that longing, the yearning to depict groups of Black folks simply existing, enjoying, and belonging to land.

ASIn works such as Georgia Hillside (Redlining) and Riverside Scene, you situate these young figures in the landscapes of Georgia. In Georgia Hillside (Redlining) you have a juxtaposition between the idyllic scene and these red lines you’ve painted onto the hillside. That juxtaposition creates a tension between the past and the present. How are you speaking about the past in the contemporary moment through these images?

TMI think a part of those images, and of that project in general, is being in direct conversation with the history of the “pastoral.” The impetus being, How do I photograph Black folks enjoying or being on Southern land? You can’t really talk about Georgian land, American land, or Southern land without talking about redlining and the systemic racial division of Black folks. It’s a systemic denial of mobility. When you think about the ways Black folks have been told they are or aren’t allowed to move around on the land, that’s what those lines are calling into question or bringing to the fore.

Another reading of those images that I thought was interesting, and that came up through conversations with friends, was that they also become lines for the eye to follow through the frame. So not only do the lines bring to the fore this not-so-subtle history of systemic racial division and prevention of mobility on land, but they also become potential pathways for connection between the figures in the images. The lines actually allow the viewer’s eye to travel playfully through the composition of the photograph. All those devices work on multiple levels in this new work.

ASIn contrast to the racial histories that have Black populations arriving in cities, in the Great Migration et cetera, these images are asking, What does it look like when Black folks are in rural landscapes? The work explores how histories of sharecropping, histories of redlining, have shaped our relationships to the land and how we operate and live on the land.

TMAnother goal of these images is to ask, How do we socialize and interact and exist in the face of historical divisions? And how do we flourish in spite of those things?

ASYou have three very different topographies in this series. In Georgia Hillside you have a hillside of course, in the Albany, Georgia image you have the sand dune scene, and then in Riverside Scene you’re on the bank of a river. I was wondering if you could talk about moving among those landscapes and why it was important to show that variation.

TMI thought it was a beautiful task to show the sheer diversity of the landscapes of Georgia. I mean, nothing about any of those landscapes tells you exactly where we are, right? There’s no “Welcome to Georgia” sign or Atlanta skyline. But you do feel a certain history of Southern landscape in the images. The way Riverside Scene is framed makes you wonder if it’s in Mississippi, maybe, or Tennessee—there’s a loose allusion to the area of the American South. By showing the region’s sheer diversity, the series suggests both that the way Black folks exist on land can’t be pinned down and that the land of the South itself can’t be pinned down. There’s a vastness and a variety to both aspects.

ASIn terms of commercial versus conceptual art, do you view them as two different practices or do you think of them all as being after the same sort of feeling?

TMThere’s definitely a difference between a Vogue cover or an i-D magazine spread and a personal project, but I certainly hope that all of my works, whether they’re commercial or personal or in the fine-art context, are in dialogue with one another. Aesthetically, structurally, conceptually, I hope together they show a growth and a continuum over time. Even if you think about my images of Beyoncé, or some of the images from I Can Make You Feel Good, in relation to this new work, I would hope you would find an aesthetic continuation, whether it’s Black folks’ relationship to nature or a reference to the historical lineages of the ways we’ve been photographed. In the Beyoncé images there are floral crowns and custom scenic painted backdrops that refer to a number of things, including African portraiture of the 1960s. I hope that my work across both commercial and fine-art contexts continues this reference to the historical and is in conversation with the ways Black folks have portrayed themselves in images with a sense of dignity and beauty over time. I also have my own conceptual concerns, like life in the South.

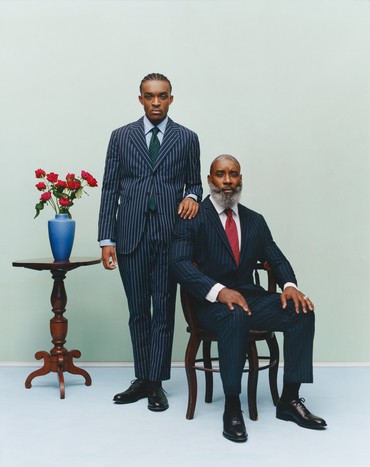

ASYou had a Gordon Parks Foundation fellowship in 2020, and you’re presenting a different body of work concerned with notions of family and the histories that produce, say, a Black middle class or upper middle class as part of that initiative. These images explore interiorities and the materiality of the interior. You’ve concentrated in a lot of ways on this idea of the family photograph.

TMThe work for the Gordon Parks Foundation reemphasizes the importance of the family photograph. There’s a significant history behind the way Black folks dress themselves for a portrait, and I argue that that process has become a central site where identity and a sense of self-determination are formed. I photographed real families in staged settings, or in domestic settings that are their own, and I emphasized the importance of these settings as sites of formation of identity. We see father-son dynamics, we see mother-daughter dynamics, and we see how these dynamics put together through images are a huge part of the formation of Black folks themselves. The family portrait is central.

ASIn viewing this new body of work, I’m struck by images like Ancestors, in which you have a mother and daughter looking at their own reflection in the mirror, and in front of that mirror there’s sort of this rephotography happening of these older images of family members in frames. It makes me think about Elizabeth Alexander’s book The Black Interior [2004], in which she argues that the Black living room was one of the first sites of freedom for us.

How important is a sense of play in your work? If you think about the work you’ve produced thus far, there are always these moments of play interwoven into the scenes. I’m thinking about the gummy-bear scene from your film, or the boys riding the tricycles. Or even in Albany, Georgia, you have a father and son playing together, you have a sister and brother throwing a football, and you have another young child in the background driving a toy truck. Can you talk about the sense of play and why that’s important to represent in your images?

TMAmy Sherald and I were talking about the sense of play in both of our bodies of work and she said she’s had conversations with artists who feel as if they’ve had to create teaching moments with their work about history and about our struggle, both of which are very important. But we both started to wonder throughout that conversation, When do we breathe? There has to be room for a range of experiences. Because if there isn’t, how do we evolve? I really like that notion and I think that question is where a lot of my work stems from. How do I offer narratives of play, of repose, of rest, of solace and belonging? Because those are images that we need to see as well. And it’s not to diminish the importance of work about history or about our struggle, which is equally real, but when you consider the history of photography, the overwhelming narrative or stereotypical image made of us really doesn’t show us at play. So where’s the radicality of just imaging two young Black men enjoying a pack of gummy bears together? I think it’s there.

Artwork © Tyler Mitchell

Social Works II: Curated by Antwaun Sargent, Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, London, October 7–December 18, 2021

The “Social Works II” supplement also includes: “Manuel Mathieu: The Delusion of Power; “Amanda Williams: What Black is This”; poetry by Raymond Antrobus and Caleb Femi;“Kahlil Robert Irving”; and “Sumayya Vally and Sir David Adjaye”