Brendan Embser is the managing editor of Aperture magazine and the editor of monographs by Deana Lawson, Philip Montgomery, Wendy Red Star, and Ming Smith. His writing has appeared in apartamento and n+1. Photo: Matthew Leifheit

By the time the twenty-seven-year-old photographer Tyler Mitchell came to prominence, a narrative was beginning to emerge about the redemptive power of fashion. Could Black photographers, working with designers, stylists, and subjects who share an identity and a sense of history, propel a new vision of desire within a notoriously exclusive sector? Could Black artists tell a new story about representation that would accrue benefits to the community rather than just propping up or satiating white gatekeepers, legacy media, luxury brands, or the guilty liberal conscience? “There is a saying,” the artist and photographer Collier Schorr has said, “‘Make one picture for “them” and another for yourself.’ Slowly try to make them want the pictures that you want.” What Mitchell wanted, not slowly but as fast as possible, was an image of Black utopia and a way of living informed by that image, a way of being and belonging as much in the frame as in life. Would photographs always dwell in the dream world, or could Mitchell bend the world to his will?

At first, it worked. Mitchell’s early portraits, influenced by the gemstone colors of Cuba and the lush green landscapes of suburban Georgia, cut a distinctive figure. There were lithe Black boys in enviable clothes in Edenic settings. There were glam girls in Gucci in grand old houses. There was light, delicate, impeccable styling. Together these young figures were presented for all the world like royalty: “teen dreams and prom queens,” as i-D put it in the magazine’s 2019 “Voices of a Generation” issue, for which Mitchell made a story about “powerful hair and beautiful faces.” In Mitchell’s photographs, whether made on his own terms or on commission for numerous magazines, the fashion-portrait gaze, that elusive combination of intensity and indifference, builds up a form of yearning that soars beyond material transactions. Between artist and subject there’s an impulse to learn more: to collaborate on the act of seeing, to collaborate on being seen. A quiet, insistent optimism. An idea, as Mitchell writes in his first monograph, I Can Make You Feel Good (2020), about visualizing Black people as “free, expressive, effortless, and sensitive.”

But a lot of that was shattered in the summer of 2020, and not because Darnella Frazier’s video of the death of George Floyd, which touched off what many writers called a “national reckoning,” was the first time Americans were confronted with a brutal manifestation of racist violence or the failed promises of emancipation. Celebrated for his fresh and youthful photographs, replete with joyful kite-flying and days spent lazing in the park, Mitchell’s work turned subtly toward a minor key. He began to make “dreamlike images,” he told me during a recent visit to his studio in Gowanus, Brooklyn, “that explore notions of paradise while simultaneously exposing their slippages and failures for Black folks.” Mitchell had just returned from Florence for the spring 2023 menswear show by the British fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner, a frequent collaborator and an intellectual, he says, who’s always providing “reading lists” about art and literature. In a new suite of work, Mitchell explained, his insistence on picturing Black men and women in states of leisure and repose underscores an ambient concern for safety. Paring down to the elements, Mitchell’s latest photographs illustrate what David Gates, writing about Toni Morrison’s novel A Mercy (2008), set in seventeenth-century America, has called a “postcolonial pastoral,” a romantic evocation of a land that’s thorned with trauma. Can a paradise lost be discovered anew?

Mitchell was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1995. As a teenager, he became immersed in skateboarding, which led in its way to photography. He studied film and television at New York University, and in 2015 he self-published a book called El Paquete, about skaters in Havana. El Paquete was picked up by Dazed magazine the same year, and the project displays Mitchell’s style in emergent force: his bold use of color in the found backdrops of green walls or pink-painted houses, his participatory elegance in seeking a sense of connection with his young subjects, and his effortless attention to fashion as a performance of self-determination. Three years later, Mitchell was commissioned to photograph Beyoncé for American Vogue’s September 2018 issue, making history, at the age of twenty-three, as the first Black photographer to shoot the magazine’s cover.

“Make one picture for ‘them’ and another for yourself”—the Beyoncé cover was certainly one for them, but also one for Mitchell himself and for everyone else; one portrait from the feature was later acquired by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. An incontrovertible triumph for Mitchell, the event might have occasioned a moment of humility for Vogue. What took so long? In the 1940s, a decade after Vogue began running photographic covers, Gordon Parks was already shooting fashion editorial for the magazine. “Vogue is not a place where you are pushy,” the late Vogue creative André Leon Talley once said. “You don’t go in there pushing and saying, you know, ‘We gotta have a black cover.’” It should be harder to believe. Still, the Queen was a kingmaker—and Beyoncé’s collaboration with Mitchell was shrewd. “I never looked at it as a door that I couldn’t open,” Mitchell told the NPR host Audie Cornish in August 2018, as the cover story rolled out. “I actually have always looked at it as a door that I was very much going to open.”

Mitchell says that his newest work is “pure,” meaning the photographs weren’t made on commission. Yet he often reuses images made for brands or publications in his own projects, exhibitions, and throughout his first monograph—and the fact that he can reuse them is a sign that they do work in multiple arenas, above all as art. The distinction, upheld by some critics and historians, appears to be of minor interest to Mitchell’s generation of photographers working between fashion and art, who want to have it both ways and often do. And anyway, as Parks, Richard Avedon, William Klein, and Irving Penn have shown—or in what the scholar Kobena Mercer would call the “belated” archival recognition of James Barnor and Kwame Brathwaite—all fashion pictures become photographs in the end. That is, they reach equilibrium with history; they become historic. If they’re good.

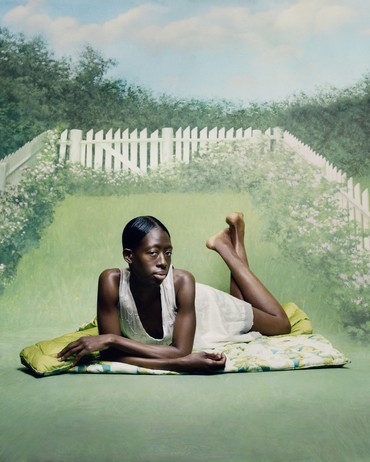

In Cage (2022), perhaps the icon of this new chapter of his work, Mitchell deploys a range of signs and structures, aligned with precision to his ongoing theme of Black quietude. A young woman in an embroidered white shift dress lies across a patterned bedspread whose chartreuse satin lining is folded up over two corners. A painted backdrop of a pale-green garden plot, demarcated by white-budded flowers, a picket fence, a thick hedgerow, and a languid sky, produces a trompe l’oeil effect, as she appears to fully occupy both the fictional space of a garden and the performative setting of a studio, as indicated by the cold, precise light falling across her beguiling face, toned arms, and feet gently crossed at the ankles. Beware the “danger of denial,” Mitchell says of Cage, meaning the denial of life and liberty, of the pursuit of happiness and of a land of one’s own.

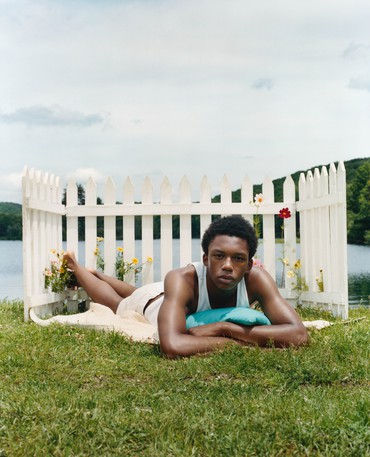

A white picket fence, a real one, also shows up in Mitchell’s earlier photograph Untitled (Southern Girls) (2021), a striking portrait of two young women in bouclé jackets, short skirts, and black heels, posed with a bicycle in the summer sun. From Southern Girls to Cage, Mitchell extends that vernacular American symbol—the picket fence as sign of both aspiration and separation—and recalls Paul Strand’s indelible photograph The White Fence (1916). Made in Port Kent, New York, when Strand was twenty-six—by uncanny coincidence, Mitchell was the same age when he made Southern Girls—The White Fence, with its stark contrast and charismatic geometry, is hailed as a breakthrough in modernist photography. It’s a picture, John Szarkowski noted, that “has etched itself into the pictorial memory of every young photographer who ever saw it.” Mark Haworth-Booth, writing in Aperture’s “Masters of Photography” series, declares that with The White Fence, Strand dispatched pictorialism and announced “the birth of a new constructive day.” The curator Peter Barberie calls The White Fence “an unforgettable representation of the American homestead, viewed from a distance as if by an outsider or by someone returning. Its concise arrangement of forms imparts all the brevity and power of a masterful short story.”

But that word: masterful. Masterly. Kerry James Marshall knocked off a vowel and called it Mastry. Riffing on his project Rythm Mastr, it’s a word “that extends Marshall’s commitment to making black subjects visible in the realm of popular culture,” as Madeleine Grynsztejn writes in the catalogue for Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, the artist’s 2016 traveling retrospective. “To failures of representation—including the lack of visibility for the black subject and depictions that compound racial stereotyping—Marshall retorts with iconoclastic images that hopefully redefine our nation’s social fabric.” Mitchell’s radiant tableau Riverside Scene (2021), which owes as much to Georges Seurat’s Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884) as to Marshall’s masterpiece Past Times (1997), is an antecedent to Cage, possibly the wished-for prospect that white-dressed woman imagines from the confinement or protection of her picket-fenced yard. “The urgency that drives you, that propels you into the studio every day,” Marshall has said, “should be the desire to see figures as yet unrealized.” Or as Toni Morrison implored, “you must write it.” Cage is Mitchell’s masterly short story, pulling into its field of vision the nineteenth-century apparatus of the backdrop, the modernist experiments with the American grain, and the long, vexing relationship between the Black figure and the landscape, the unholy mix of persecution and potential.

In 2020, Mitchell was awarded a fellowship from the Gordon Parks Foundation, for which he made a series of domestic still lifes that recall both Parks’s midcentury work and Deana Lawson’s long-standing fascination with family pictures and the Black home as site of cosmological memory. Mitchell appears to deepen his connections with Parks’s legacy in several new photographs that also move toward the elemental, stripping away sartorial flair in favor of arcadian tranquility. Mud, water, sunlight, and heat are the primary materials in Rapture, The Heart, Treading, Simply Fragile, Distillation, and the diptych Self Decoration (all 2022). Some were made in upstate New York, along lakes and verdant territory seemingly unchanged for centuries; others are the results of an elaborate studio setup. Here, young men seek solace through ablutions. They are each alone in their own thoughts and worlds. Resting on the nose of a shirtless boy, a large bug is the source of captivation in the portrait Simply Fragile, an image that yields a startling and poignant resonance with Parks’s Boy with June Bug, Fort Scott, Kansas (1963), in which a Black boy lies in green and lavender grass, eyes closed, pulling a bug along his forehead with a taut white string.

Boy with June Bug was originally published in a Life magazine story called “How It Feels to Be Black,” an evocative fictional sequence about a “recaptured boyhood of joy, of longing and sudden violence.” The feature includes Watering Hole, Fort Scott, Kansas (1963), Parks’s overhead image of five Black boys in silver-blue water, diving and swimming, standing in the shallows, being together. Watering Hole becomes a speculative antecedent to Mitchell’s Distillation, also made from above, in which water rushes over the body of a young man bathing in a rich white foam. The wet footprints across worn floorboards in Tenderly might be those of Parks’s watering hole boys. And the single hand emerging from the glossy flaxen mud in Mitchell’s Rapture calls out to Parks’s Untitled, Fort Scott, Kansas (1963), in which a hand is raised from beneath green water—is it a plea for help or a sign of life? It’s the “postcolonial pastoral” again, with lush breezes and the slightest tremor of danger. Yet, decades apart, Mitchell’s and Parks’s photographs in nature appear to restore to Black boys a sense of private pleasure and wonderment.

“Gordon Parks had the same experience, in terms of remixing the concept of fashion,” the photographer and historian Deborah Willis said in an interview with Mitchell for Antwaun Sargent’s book The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion (2019). (Mitchell contributed the book’s cover image, a portrait of the model Ugbad Abdi originally published in Vogue.) “Those images from the civil rights movement, and when he was in people’s homes, he could see how people were dressed, and he knew that they were not dressing for his camera, but for themselves.” Willis had been Mitchell’s professor at New York University; no living scholar has done more than she to expand the history of Black photographers and of Black subjects in front of the lens, and her signal contributions include her building of a multigenerational network of writers and artists—among whom Mitchell is a leading light—with a similar drive to advance the field.

Willis wrote an essay for I Can Make You Feel Good and has done many interviews with Mitchell, one of them online for An Imaginative Arrangement of the Things before Me, his Gordon Parks Foundation exhibition in 2021. For Willis, the parochial divide between fashion and fine art is largely irrelevant. The connections, which Parks made across the genres of documentary, fashion, and filmmaking throughout his career, are more intriguing as a font of wisdom about how a photographer develops a career with verve and integrity. And a photograph like Mitchell’s Chrysalis (2022) is a successor, in a way, to Parks’s vision and Willis’s guidance. A boy lies on a twin bed, eyes closed, in a plain room with unpolished floorboards. Those expert seams on navy pants, the supple light over luminous skin, the perfect balance of color between the ocher sheets and the mint-green blanket, a patterned bedspread that bears a resemblance to the one in Cage: could this be a fashion picture? But the title Chrysalis, referring both to the pupa of a butterfly and a protected state, implies that the image might be a form of autobiography, a story about emergence. The mosquito net casts a sepia glow; held aloft by wires to form the pentagonal shape of a pavilion, it looks like the rough draft for a Do Ho Suh sculpture. If a boy is protected, can there be freedom in dreaming?

There’s always a temptation to imagine the purity of the early American landscape without any regret for what happened after. Even a hike in the forests of the Hudson Valley can evoke a primal sense of communing with an ancient territory, followed by the relief and trepidation in knowing that the city is just nearby—the empire is there, humming along, waiting for nothing but expecting everything. The pleasures and the perils await on every street. If Mitchell has made a world of joy and exuberance, he asked himself in creating this new work, but “on the other side of the hill is this political or historical or systemic danger preventing that from happening, how do I draw that out more, or have a conversation around that?” One response might be found in the enigmatic triptych that serves as a coda to these new photographs. Into his studio Mitchell brought a large, yellow, coffinlike container and filled it with soil, which ripples like a corrugated tin roof. Steadily, a young man pulls over the box a cloth backdrop painted to resemble a blue, cloud-scattered sky. In the final panel, the boy has disappeared altogether. A burial. A dream deferred. A broken promise in the promised land. Stenciled in black letters on the side of the box, Mitchell discovered the warning that gave the piece its title: “Fragile—Protect from All Elements.”

Tyler Mitchell: Chrysalis, Davies Street, London, October 6–November 12, 2022

Artwork © Tyler Mitchell