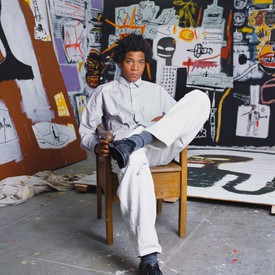

Born in San Diego in 1992, Kahlil Robert Irving has an MFA from the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts, Washington University, St. Louis, and a BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute. In 2019, Callicoon Fine Arts mounted his second solo exhibition in New York, Black ICE. He was awarded a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Biennial Award in 2019 and a Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant in 2020. In the fall of 2021, Irving will participate in the New Museum Triennial, cocurated by Jamillah James and Margot Norton.

Antwaun Sargent is a writer and critic. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books, among other publications, and he has contributed essays to museum and gallery catalogues. Sargent has co-organized exhibitions including The Way We Live Now at the Aperture Foundation in New York in 2018, and his first book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, was released by Aperture in fall 2019. Photo: Darius Garvin

Antwaun SargentYou make ceramic sculptures that also use found debris, sourced from the streets. How did this come about?

Kahlil Robert IrvingThe work has grown over the past ten years, but it originates in my first time going to New York City—seeing the ground partitioned by roads from the airplane, and then seeing the big buildings coming out of Manhattan. This implied texture or geometry in three-dimensional space made me think about where I am and where things are, and then about my education in sculpture in relation to my lived experience. Making sculptures that reference the street or the built environment has been a way to decipher the problems and the infrastructure behind the life we’re all living but few are really seeing. It really came about in college, when I was studying abstraction and listening to artists, specifically Kerry James Marshall, talk about representation and content colliding to tell narratives in painting. So I went forward past the nonrepresentational abstract works I was making to a place where I was adding forms—to-go boxes, soda bottles—to give an engagement with scale that the viewer could understand. Another thing, though: everything in my sculptures is made in the studio. The current work has an even more layered presentation of being found or weathered with time, but in fact it’s all constructed that way.

ASWhat is it about the street that you want to situate within an artwork?

KRITo pull up a piece of asphalt exposes the layers underneath the road on which we’re walking or driving, and at the same time puts up a direct, physical impediment in front of people. It’s a gesture for those who cannot perceive the issues of this world, even though they’re hypervisible for the people who are affected by that built environment. For me, the ground is this infinite frame by which narratives and stories are told or understood or traversed; the objects embedded in the asphalt hold stories that aren’t getting told, they’re just getting built over and on top of. How do you deconstruct and reconstruct a reality in this very terse and ambiguous history that’s all built around material? In St. Louis, where I grew up and where I’ve returned to, it’s all built out of bricks and ceramic, or I should say silicate material. Silicate is a glass agent that occurs in the earth and can be pulled out and extracted. It’s what makes clay hard. It’s what makes glass a slow-moving material that’s always in motion. Or concrete, a material that goes through either an endothermic or an exothermic reaction that then catalyzes materials and gives them stability.

ASHow are you thinking about the objects you re-create, from the car air-freshener to the Newport box? How are you thinking about their relationships to the people in the communities that walk that ground?

KRIDowntown Norfolk, Nebraska, 1998 [2017], for instance, comes through an experience of making a specific autobiographical narrative and relationship present. It signifies a personal lived experience, and then these Newports are a signifier or a moment that many people can connect around and understand and relate to. There are multiple entry points into the work, but the signifiers I’m using are either situational or relevant or pertinent to a specific narrative. And with the sculpture, I’m also invested in exploring a signifier that is illegible. They’re so abstract that that complication almost leads to an end.

ASThat play between legibility and illegibility is fascinating. Could you talk about that interplay?

KRIBy refusing to make everything explicitly legible, the work allows there to be space for the ways Black people live . . . for more of the complicated nature of our existence in places and spaces. There’s a certain level of freedom there that I appreciate.

ASFor me, one of the great powers of this work is that these objects that you create are gateways to memories, and that in making these objects, a lot of them are flattened or crushed onto the surface.

KRII’m going to describe it like this: as I was growing up, one of the most important albums for me was Still Standing by Goodie Mob featuring OutKast, from 1998. The song “Black Ice” has remained key. I did an interview for the New Museum Triennial and I talked about Michael Eric Dyson, who wrote this book Holler If You Hear Me: Searching for Tupac Shakur [2001], which is about how Tupac constructed his music in relationship to how he lived and navigated his life within the reality of being Black in America. The way Professor Dyson talked about Tupac in an interview on 60 Minutes brought out the complicated reality in which my work aims to participate, where signs and symbols can exist and be collapsed but also be very present, forthright, and direct. Only certain experiences will be able to decipher that. I cherish lyricism and the lyrical—a lyrical flourish comes not only through the complicated nature of word usage, but also with the reality of having to navigate multiple spaces, inhabitable for some, uninhabitable for others, but also a space for freedom. Blackness is space for invention.

Artwork © Kahlil Robert Irving

Social Works II: Curated by Antwaun Sargent, Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, London, October 7–December 18, 2021

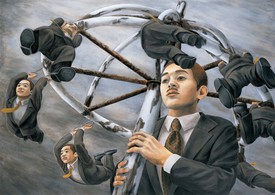

The “Social Works II” supplement also includes: “Tyler Mitchell: A New Landscape”; “Amanda Williams: What Black is This”; poetry by Raymond Antrobus and Caleb Femi; “Manuel Mathieu: The Delusion of Power”; and “Sumayya Vally and Sir David Adjaye”