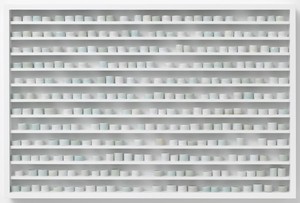

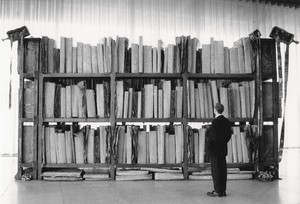

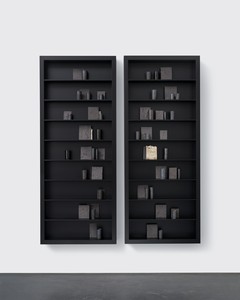

For this new body of work, I have made a series of conversations about materials with architectural space. How people walk through spaces, how they encounter what I make, how it is possible to make work to pause the world a little, is my imperative. At its core is one simple question: it is about what it means to belong in one place at one time.

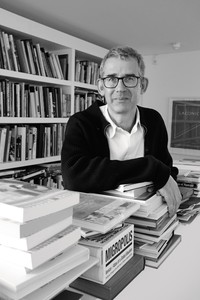

—Edmund de Waal

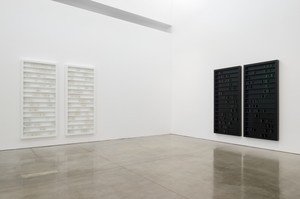

Gagosian Beverly Hills is pleased to present new works by Edmund de Waal for his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles.

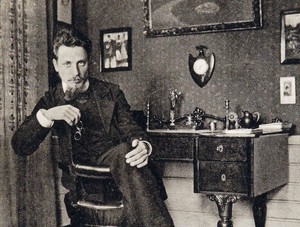

De Waal’s art and literature speak to his enduring fascination with the nature of objects, and the narratives of their collection and display. A potter since childhood and an acclaimed writer, his obsession with porcelain or “white gold” has led to encounters with many people and places that help deepen his understanding of the nature of the material. His latest book, The White Road: Journey into an Obsession (2015), traces the historical evolution of porcelain from its origin in Jingdezhen, China, through developments in Venice, Versailles, Dresden, Cornwall, and the Cherokee Country of South Carolina.

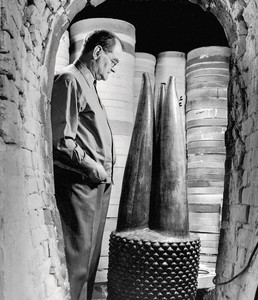

From simple pairs to complex multitudes of small objects, de Waal draws inspiration from many sources, including the poetry of Paul Celan and the musical compositions of John Cage. At the heart of this exhibition is a series of responses to the Schindler House on Kings Road in Los Angeles; a revolutionary building from 1922 by the Viennese émigré architect, Rudolph Schindler. For de Waal, the Schindler House is “improvisatory architecture,” which offered a new way of living and working, a new set of possibilities for materials, a new architecture for a new city. It was here that, according to de Waal, Cage “began to clear his mind.”