A potter since childhood and an acclaimed writer, Edmund de Waal is best known as an artist for his large-scale installations of porcelain vessels, which are informed by his passion for architecture, space, and sound.

A white bottle is all that remains.

— Giorgio Morandi, letter to Lamberto Vitali, 1962

beginnings

If you make things and put them down on a table or a shelf in your studio, or if you take a cup from the cupboard and make yourself coffee and then wash it up and stack it on the draining board by the sink, you are on the edges of still life. Still life happens. Notice the strange interstices between the things that crowd our life, our vision. There are felicities in the way these cups meet or the spaces between these wet porcelain vessels that congregate on the board next to my potter’s wheel. These are serendipities, moments of cadence.

And these moments illuminate something at the heart of still life. This world of things is full of small epiphanies.

That is a start. It is only a start. To catch the fugitive apprehension and make it slow into the fullness of Chardin’s glass of water (three cloves of garlic and a brown jug), Cézanne’s apples, Morandi, will take a lifetime, but as Rilke wrote, “You must change your life.”

And he should know. He wrote poems, Ding gedichte, that were still lives too.

senza fretta

One day in 1960, Morandi paints the large black jug with the high looped handle and the high beaked spout with six canisters in front of it. These are white and black and orange and beige. They stockade the jug. The jug holds the center of the picture. The ground is ochre. The background is gray, a flat gray. It takes time.

Another day in 1961, the jug faces to the right. It is bigger. There are four canisters: the orange and black in the center, the flanking ones now cream. The background is scumbled. It is a quicker painting.

His signature takes the stage too. The light is different. The foreground is closer in one than in the other. The objects are the same but transformed.

It makes me think of Wallace Stevens’s “Anecdote of the Jar,” the way that putting something down in the world changes the energy field of everything around it:

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.It took dominion everywhere.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

When an object takes dominion, it takes over a space in the world, a space in our visual field, and a space in our thinking. This is the paradox about these small paintings of pots and tins, painted in a studio no larger than a box room. The space they create is as big as Tennessee.

Once again

I’m asked again and again about why I make vessels again and again. Why sit low down at my potter’s wheel—my seat is an old wooden bench that I’ve sat on for thirty years—turn to my left and pick up a small ball of porcelain clay, throw it into the center of a revolving wheel, wet my hands, bring them together over the clay, and start another vessel? Don’t you get bored? I’m asked. They are so simple, just cylinders, a few centimeters high, barely inflected forms, a slight change of energy at the rim. You use the same clay, the same wheel, the same few tools.

And my answer is that to spend time is to explore time. That this process is not a means to an end. Make the pots in order to have them finished so that they can be red and glazed and sanded down so that I can arrange them in compositions. Taking this time to make is a way of finding a space to think about music and space and language. It is a kind of renewal, a starting over.

Morandi’s response to a question was that “I must always start from the beginning, and ought to burn what I’ve done in the past.”

Starting from the beginning meant “marks traced out along the outlines of the objects upon the ground sheet, in order to verify the mapping and to preserve the structures of the still life in their placement; the circumspect shifting of the objects upon the flat surface, by means of the handles of the longest brushes; the use of the compass and the straight-edge as instruments of geometrical and proportional verification; the presence of a mobile frame, ‘a white Leonardo-esque vehicle,’ constructed so as to grade and guide the light from the large window; the lines marked in chalk on the floor, after a pause in working, the precise position and chosen point of view.”

Here is rigor, a paring back of the extraneous elements in order to create a set of possibilities that expands the world.

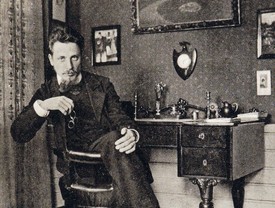

Via Fondazza

I think of two men I admire who lived at home in their familial apartments with mothers or sisters for their whole lives. One is Primo Levi, who lived in Corso Re Umberto in Turin. The other is Morandi, who lived in Via Fondazza in Bologna. Levi goes to work every day as a chemist in a paint factory, where he studies how to calibrate fine distinctions in the way light works in paint. It is a career forty years long.

To get exactly the correct equipment to create his experiments he learns to blow glass and polish it. He makes his own crucibles. He writes in The Monkey’s Wrench of “the advantage of being able to test yourself, not depending on others in the test, reflecting yourself in your work. On the pleasure of seeing your creature grow, beam after beam, bolt after bolt, necessary, symmetrical, suited to its purpose.”

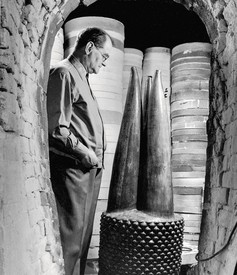

Morandi goes to work every day through his sister’s bedroom to the studio with its one window and one bare bulb to calibrate fine distinctions. He pours different colored pigments into transparent glass bottles, whitewashes tins of Ovaltine, colors vases to change their visual density.

To get exactly the correct surfaces on which to place his objects he creates three tables of varying heights, two built by himself, one at eye level, one above eye level, and one below.

In Primo Levi’s story “The Mnemogogues” an aging Doctor talks to a young Doctor he calls Dr. Morandi about “the definitive prevalence of the past over the present, and the final shipwreck of every passion, except for his faith in the dignity of thought and the supremacy of the things of the spirit.”

“Before I die I should like to bring two paintings to completion,” said the real Morandi. “What matters is to touch the core, the essence of things.” And more cogently still, “Nothing is more abstract than reality.”

Dust

I recently finished a book about the color white. It was a kind of autobiography, mapping my obsession with white through my journeys with porcelain. It was a journey to China, Meissen in Germany, Cornwall in England, the Appalachian Mountains and Dachau; a journey into the history of the material. It became a history of dust. How this beautiful clay had affected those who searched for it and used it—the eddying white dust in mines and workshops and factories across a thousand years. I wrote about my own apprenticeship and how I swept up the dust day after day for years, breathing in the dangerous clouds of silica. And when I’d finished this book I realized that I’d ended my previous book on my family writing about the dust of Odessa, the dust of archives in Paris and Vienna.

And I read John Rewald on the dust of Morandi:

They must have been there for a long time; on the surfaces of the shelves or tables, as well as on the flat tops of boxes, cans, or similar receptacles, there was a thick layer of dust. It was a dense, grey, velvety dust, like a soft coat of felt, its color and texture seemingly providing the unifying element for these tall bottles and deep bowls, old pitchers and coffee pots, quaint vases and tin boxes. It was a dust that was not the result of negligence and untidiness but of patience, a witness to complete peace. In the stillness of this humble retreat from all the excitement of an agitated world, these everyday objects led their own, still life. . . . The dust that covered them was like a mantle of nobility, endowing them with a special purpose and meaning, and attesting to the faithful company they had been keeping with Morandi for many, many years.

Perhaps my obsession with Morandi is actually with dust; the idea of dust, how time settles and stirs, how we trace time. Rewald finds the right word for this. It is “witness.”

The end of the shelf

This exhibition at Artipelag allows me to put my work near that of Morandi. I struggle to find the right word. Conversation and dialogue and homage and installation and intervention are such harsh Art World terms. I feel great anxiety and tenderness about bringing my own work into such proximity with Morandi. He hated a fuss and I don’t want him to feel fussed over. I want my work to be on nodding terms with him. I don’t need anything more.

So what I’ve done is to think of his compositional rigor, the ways that he makes us move closer or further away, the way he alters our sense of gravity, of being grounded, or hovering or floating. The way he thinks about the ends of shelves, the end of the line, edges. The ways he returns and repeats.

And then I’ve used this syntax to bring some work of mine into these clean, light-infused spaces for the summer months.

There are pieces above you, some suspended, some on high shelves. There are works to move amongst, a vitrine placed far away, cabinets in series on walls. They are elegies, cloudscapes, fragments of song or time-keeping, walks through cities, memories of people, distractions, recalibrations, marginalia, readings, soundings. They are my way of keeping time. They are a kind of witness. They are vessels made from porcelain, stilled. They are still life.

Anecdote of the Jar from The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens by Wallace Stevens, copyright © 1954 by Wallace Stevens and copyright renewed 1982 by Holly Stevens. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Witness by Edmund de Waal was originally published by Artipelag in the 2017 catalogue Edmund de Waal/Giorgio Morandi. Artwork © Edmund de Waal. Artwork © 2017 Giorgio Morandi/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome